- 336 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

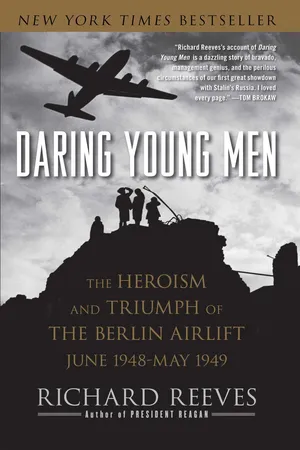

About this book

In the early hours of June 26, 1948, phones began ringing across America, waking up the airmen of World War II—pilots, navigators, and mechanics—who were finally beginning normal lives with new houses, new jobs, new wives, and new babies. Some were given just forty-eight hours to report to local military bases. The president, Harry S. Truman, was recalling them to active duty to try to save the desperate people of the western sectors of Berlin, the enemy capital many of them had bombed to rubble only three years before.

Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin had ordered a blockade of the city, isolating the people of West Berlin, using hundreds of thousands of Red Army soldiers to close off all land and water access to the city. He was gambling that he could drive out the small detachments of American, British, and French occupation troops, because their only option was to stay and watch Berliners starve—or retaliate by starting World War III. The situation was impossible, Truman was told by his national security advisers, including the Joint Chiefs of Staff. His answer: "We stay in Berlin. Period." That was when the phones started ringing and local police began banging on doors to deliver telegrams to the vets.

Drawing on service records and hundreds of interviews in the United States, Germany, and Great Britain, Reeves tells the stories of these civilian airmen, the successors to Stephen Ambrose’s "Citizen Soldiers," ordinary Americans again called to extraordinary tasks. They did the impossible, living in barns and muddy tents, flying over Soviet-occupied territory day and night, trying to stay awake, making it up as they went along and ignoring Russian fighters and occasional anti-aircraft fire trying to drive them to hostile ground.

The Berlin Airlift changed the world. It ended when Stalin backed down and lifted the blockade, but only after the bravery and sense of duty of those young heroes had bought the Allies enough time to create a new West Germany and sign the mutual defense agreement that created NATO, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization.

And then they went home again. Some of them forgot where they had parked their cars after they got the call.

Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin had ordered a blockade of the city, isolating the people of West Berlin, using hundreds of thousands of Red Army soldiers to close off all land and water access to the city. He was gambling that he could drive out the small detachments of American, British, and French occupation troops, because their only option was to stay and watch Berliners starve—or retaliate by starting World War III. The situation was impossible, Truman was told by his national security advisers, including the Joint Chiefs of Staff. His answer: "We stay in Berlin. Period." That was when the phones started ringing and local police began banging on doors to deliver telegrams to the vets.

Drawing on service records and hundreds of interviews in the United States, Germany, and Great Britain, Reeves tells the stories of these civilian airmen, the successors to Stephen Ambrose’s "Citizen Soldiers," ordinary Americans again called to extraordinary tasks. They did the impossible, living in barns and muddy tents, flying over Soviet-occupied territory day and night, trying to stay awake, making it up as they went along and ignoring Russian fighters and occasional anti-aircraft fire trying to drive them to hostile ground.

The Berlin Airlift changed the world. It ended when Stalin backed down and lifted the blockade, but only after the bravery and sense of duty of those young heroes had bought the Allies enough time to create a new West Germany and sign the mutual defense agreement that created NATO, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization.

And then they went home again. Some of them forgot where they had parked their cars after they got the call.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Daring Young Men by Richard Reeves in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & 20th Century History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

“City of Zombies”

June 20, 1948

THE NEWSWEEK HEADLINE WAS “DATELINE GERMANY, 1948: the Big Retreat.”

The dispatch below was from James O’Donnell, the magazine’s Berlin bureau chief, reporting on the exodus of American and British officials and soldiers from the city as the Soviet Union took complete control of the old German capital.

After the Russians claimed control, O’Donnell reported, General Lucius Clay, the American military governor of Germany, had cabled Washington that he intended to order B-29 Superfortresses to begin attacking Soviet installations across Germany—and beyond. Washington responded, “Withdraw to Frankfurt.”

Then, the Newsweek story continued, “At 1000 hours Saturday, the American cavalcade rendezvoused with the British . . . The bedraggled and demoralized caravan proceeded along the 117 miles of Autobahn to Helmstedt in the British zone . . .”

At the bottom of the two-column account, published on August 8, 1947, Newsweek added that the story was a fantasy, but still a plausible scenario:

This fantasy does not sound so fantastic in Berlin as it does in the United States. For the German capital has been buzzing with rumors that the Western Allies would this winter recognize the irrevocable division of Germany and pull out of Berlin. The Germans probably envision some dramatic exodus. Actually, policy makers in Washington have seriously considered quietly leaving Berlin for the Russians to rule—and feed.

The magazine had found a way, an anonymous source, to tap into the cable traffic between Berlin and Washington that spring, as memos flew back and forth predicting Soviet pressure on the small occupation governments of the United States, Great Britain and France. Robert Murphy, the State Department’s man in Berlin, Clay’s political advisor, cabled back to Washington: “The next step may be Soviet . . . demand for the withdrawal from Berlin of the Western powers. In view of the prospect that such an ultimatum would be rejected, the Soviets may move obliquely, endeavoring to make it increasingly impossible or unprofitable for the Western powers to remain on; for example by interfering with the slender communications between Berlin and the Western Zone, taking further actions towards splitting up the city . . . Our Berlin position is delicate and difficult. Our withdrawal, either voluntary or non-voluntary, would have severe psychological repercussions which would, at this critical stage in the European situation, extend far beyond the boundaries of Berlin and even Germany. The Soviets realize this full well.”

It was not fantasy anymore on June 24, 1948. That day, the final edition of the Times of London reported:

NEW RUSSIAN RESTRICTIONS IN BERLIN

BERLIN—Shortly after 1 o’clock this morning the Soviet military administration for Germany announced that all railway traffic on the line between Berlin and Helmstedt had been stopped in both directions. The Soviet authorities have also given instructions to the Berlin electricity company that deliveries of current from the eastern to the western sectors of Berlin are to be stopped immediately. These measures followed the announcement yesterday that the three Western powers intend to introduce the new West German currency into their sectors in Berlin.

The instructions for the stoppage of this important railway traffic which, air traffic apart, is the only means by which Allied and German supplies can now be brought from the Western zones into Berlin means that Allied zones of the city are essentially isolated.

So, the rumors were true—about half of them. Talk of the introduction of new currency by the Western Allies to replace worthless Nazi Reichsmarks, and of a Soviet blockade, had been both boiling and freezing life in Berlin for weeks. The people of the broken city, with its four occupation sectors—Soviets in the eastern sector and Americans, British and French in western neighborhoods—had been trading information and rumors of devalued currency, or the withdrawal of American, British and French troops, or even another war.

There were hundreds of thousands Red Army troops (at least twenty divisions in various states of combat readiness) in and near East Germany. The Soviets also had more than 2,500 combat aircraft, fighters and light bombers in East Germany and another 1,500 or so in Eastern European countries. That compared with 16,000 Allied troops, most of them military police and engineers, fewer than 300 American combat aircraft and perhaps 100 British fighters and bombers. There were another million or so Soviet troops in the rest of Eastern Europe, surrounding East Germany. Allied troop strength in all of western Germany was 290,000 men but only one or two combat-ready brigades.

The military imbalance was a regular feature of secret reports submitted by a Berlin representative of the West German Social Democratic Party,* which was headquartered in Hannover, in western Germany. He signed each message “WB.” Willy Brandt was a thirty-five-year-old journalist who had fled Hitler’s Germany and become a Norwegian citizen. He returned to Berlin in 1945 as the press attaché at the Norwegian mission. Then, in 1947, becoming a German citizen again, he began reporting weekly to West German SPD leaders on the situation in Berlin. In a secret dispatch labeled number 59, on June 14, 1948, he wrote:

The English political officers are very nervous internally because of the new and possible Russian strangulation measures. An informant from SED [the Socialist Unity Party of Germany, controlled by the German communist party, which was in turn controlled by Soviet occupation authorities], might be interesting in this context: Walter Ulbricht, an important SED official, has said (privately) that the western powers will be forced to leave Berlin before July 15. These circles obviously believe that preventing supply will make the population prefer a withdrawal of the western allies to anything else. Personally, I am inclined to believe that the Russians will not carry it to the extremes. Talking to the English and Americans I gained the impression that they by now have realized the disastrous consequences of a possible withdrawal and are therefore serious in declaring their unwillingness to withdraw. Two days ago a well-informed American again explained to me that their highest offices recognize the political necessity to keep Berlin . . . The aforementioned source confirmed that the Russians had tested the waters in the past two weeks and that high American and Russian representatives talked about the currency reform . . .

Now, ten days after Brandt’s memo, which was wrong about American intentions, truck and automobile traffic from the western zones was indeed strangled. The Soviets announced that the Autobahn from Helmstedt in the British Zone, running through East Germany to Berlin, was being closed for “technical reasons.” The stated technical reason was to make repairs on the dozens of bridges between Helmstedt and Berlin. With Soviets preventing rail travel through East Germany by blocking or ripping up track, and using patrol boats to blockade rivers and canals, the 2.1 million people of western Berlin were effectively cut off from the world. The lifeline to western Berlin, bringing in its food and fuel, more than 15,000 tons each day, was cut. Allied statisticians estimated that the western sectors of the city had enough food to last about thirty-five days, and enough fuel to last forty-eight days.

There were, however, six months of medical supplies stockpiled in western Berlin. Dr. Eugene Schwarz, Chief Public Health Officer in the American Sector, had been told in January by a friend, Ada Tschechowa, that when her husband had delivered a Soviet general’s baby, the new father and his friends had drunkenly toasted both the infant and the day they would blockade the city and drive out “the swine”—the British and the Americans. Dr. Schwarz had passed the story up the line to General Clay, who dismissed it as drunken gossip. On his own, Dr. Schwarz had begun secretly filling warehouses with emergency supplies.

The first public reaction from the Allies came from one of Clay’s subordinates, the commander of civil government in the American Sector of Berlin, Colonel Frank Howley, a former Philadelphia advertising executive. He was, in effect, the city manager of one-quarter of Berlin. An Irishman, and a volatile one, he was called “Howling Howley” for a reason. Hearing of the blockade, he rushed to the studio of RIAS, “Radio in the American Sector,” on his own and announced: “We are not getting out of Berlin. We are going to stay. I don’t know the answer to the current problem—not yet—but this much I do know: The American people will not allow the German people to starve.”

General Clay, also the commander of all American troops in Europe, had been in meetings in Heidelberg, the U.S. military headquarters, and flew back to western Berlin, where he lived. He told his counterparts, the British and French commanders, that he was sure the Russians were bluffing, and he proposed sending an armored convoy of 6,000 men to race down the Autobahn from Helmstedt to Berlin, using American engineers to repair the bridges—if there was anything actually wrong with them.

Lucius DuBignon Clay, fifty years old, a 1918 graduate of the U.S. Military Academy, was both brilliant and aloof, a courtly but distant man, a descendant of Henry Clay and the son of a U.S. senator from Georgia. He wore few decorations on his uniform and was a chain-smoker, rarely photographed without a Camel in his hand. He usually skipped lunch—he lost thirty pounds in Germany—but was said to drink thirty cups of coffee a day. He sometimes worked seventy-two hours at a stretch, with his Scottie, George, at his feet, and was one of the very few Americans ever to become a four-star general without commanding men in combat. An engineer and administrator, he was always needed more urgently at home than on fields of battle. In World War II, he served as what amounted to a national czar of military production and procurement. He came to Europe only once during the war, at the personal request of the supreme Allied commander, General Dwight D. Eisenhower, to figure out how to move men and equipment inland from the beaches after the invasion of France on D-Day, June 6, 1944.

Clay’s British counterpart in Germany, General Sir Brian Robertson, described him as “looking like a Roman emperor and sometimes acting like one.” Among the Americans who served him there was a joke that Clay was a real nice guy when he relaxed, but he never relaxed. He had what amounted to dictatorial powers in the American Zone of Germany and Sector of Berlin. Believing the Russians would back down in the face of force, he wanted his troops in motion before any of his superiors in Washington—the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Omar Bradley, Secretary of the Army Kenneth Royall, Secretary of Defense James Forrestal and President Harry S. Truman—could order him to stop.

Clay had already discussed the convoy idea with General Curtis LeMay, commander of USAFE (United States Air Force Europe). LeMay was a bombing legend before he was forty for developing the block formation of B-17s and B-24s, Flying Fortresses and Liberators—bombers that destroyed much of Germany—and the use of incendiary bombing that destroyed Japan’s cities. Characteristically, he had already prepared a contingency bombing plan to begin if a convoy was blocked by the Red Army: LeMay believed American planes could destroy every Soviet airfield and every airplane on the ground in Germany in a few hours, because the Russians routinely and irrationally made their own planes perfect targets by lining them up in orderly rows. “They vetoed the plan,” said LeMay in disgust. In his lexicon “They” usually meant liberal politicians in Washington. “The Berlin crisis,” he said, “is a logical outgrowth of the God-bless-our-buddy-buddy-Russians-we-sure-can-trust-them-forever-and-ever philosophy that flowered way back in the Roosevelt Administration.” And, as far as the Soviets were concerned, he said, “We could have done a pretty good job of cleaning out the Russian air force in one blow. They had no atomic capability. Hell, they didn’t have much of any capability.”

But before Washington knew any of this had happened, Clay and LeMay’s plans were stopped by the British military governor, General Robertson. “If you do that, it’ll be war, it’s as simple as that,” Robertson told Clay. “If you do that, I’m afraid my government could offer you no support—and I’m sure the French will feel the same.”

The early hours of the next morning brought the daily American “teleconference”—Clay and officials in Washington held coded tele-typed conferences most days, with the decoded words slowly tapping out on huge lighted screens in the Pentagon and the bunker under American military headquarters in Berlin. By the time he left the bunker, the American commander had received his orders: Clay was told to take no action that risked war with the Soviet Union. It was a frustrating setback for Clay. He was sure that the Soviets did not want war. He was equally sure that a stable, free Europe depended on an economically strong and democratic Germany, with an elected parliament, an executive and an independent judiciary. Clay was a hard man, but, above all, he was a true democrat. His views of Germany’s future were often quite different from those in Washington—and in London and Paris—where many high officials preferred a Germany forcibly kept too weakened to begin another war. Usually he got his way by acting preemptively or threatening to quit in letters and during teleconferences. He was a man with many antagonists, beginning with Secretary of State George Marshall and his celebrated assistants, Robert Lovett and George Kennan, who usually believed Clay was trying to move too fast toward a self-governed Germany rebuilding its industrial power. All admired his talent, but few found it easy to work with him.* One of his adversaries was his superior, General Bradley, who had said secretly, back in April, “Shouldn’t we announce the withdrawal from Berlin ourselves to minimize the loss of prestige?”

Clay’s answer, via teleconference, was:

I do not believe we should plan on leaving Berlin short of a Soviet ultimatum to drive us out by force if we do not leave. At the time we must resolve the question as to our reply to such an ultimatum. The exception which could force us out would be the Soviet stoppage of all food supplies to German population in Western sectors. I doubt that Soviets will make such a move because it would alienate the Germans almost completely, unless they were prepared to supply food for more than two million people.

The official population of the western sectors was just over 2.1 million. The number for the whole city of 355 square miles, a bit more than the area of the five boroughs of New York City, was about 3.1 million, compared with 4.3 million in 1938. There were only 1,285,376 male Berliners after the war.

In that teleconference, Clay ended angrily. “Why are we in Europe? We have lost Czechoslovakia. We have lost Finland. Norway is threatened . . . If we mean we are to hold Europe against communism, we must not budge . . . If America does not know this, does not believe the issue is cast now, then it never will and communism will run rampant. Once again, I ask, do we have a German policy?”

Hearing of the latest temporizing in Washington from Clay, Robertson then suggested that perhaps the Allies could expand the daily flights that brought provisions into the city for their own troops. They had done that in March, three months earlier, when the Sov...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Introduction

- 1. “City of Zombies” June 20, 1948

- 2. “Absolutely Impossible!” June 28, 1948

- 3. “Cowboy Operation” July 29, 1948

- 4. “Black Friday” August 13, 1948

- 5. “We Are Close to War” September 13, 1948

- 6. “Rubble Women” October 29, 1948

- 7. “It Looks Like Curtains” November 28, 1948

- 8. “Flying to His Death” December 6, 1948

- 9. “Stalin Says . . .” January 30, 1949

- 10. “Zero-Zero” February 20, 1949

- 11. “A Big Hock Shop” March 12, 1949

- 12. “Here Comes a Yankee” April 16, 1949

- 13. “We Are Alive!” May 12, 1949

- Epilogue

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Acknowledgments

- Index

- About the Author

- Photo Credits

- Footnote