eBook - ePub

Into the Rising Sun

In Their Own Words, World War II's Pacific Veteran

- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In his award-winning book Beyond Valor, Patrick O’Donnell reveals the true nature of the European Theater in World War II, as told by those who survived. Now, with Into the Rising Sun, O’Donnell tells the story of the brutal Pacific War, based on hundreds of interviews spanning a decade.

The men who fought their way across the Pacific during World War II had to possess something more than just courage. They faced a cruel, fanatical enemy in the Japanese, an enemy willing to use anything for victory, from kamikaze flights to human-guided torpedoes. Over the course of the war, Marines, paratroopers, and rangers spearheaded D-Day–sized beach assaults, encountered cannibalism, suffered friendly-fire incidents, and endured torture as prisoners of war. Though they are truly heroes, they claim no glory for themselves. As one soldier put it, "When somebody gets decorated, it’s because a lot of other men died."

By at last telling their stories, these men present a hard, unvarnished look at the war on the ground, a final gift from aging warriors who have already given so much. Only with these accounts can the true horror of the war in the Pacific be fully known. Together with detailed maps of each battle, Into the Rising Sun offers a complete yet deeply personal account of the war in the Pacific and a ground-level view of some of history’s most brutal combat.

The men who fought their way across the Pacific during World War II had to possess something more than just courage. They faced a cruel, fanatical enemy in the Japanese, an enemy willing to use anything for victory, from kamikaze flights to human-guided torpedoes. Over the course of the war, Marines, paratroopers, and rangers spearheaded D-Day–sized beach assaults, encountered cannibalism, suffered friendly-fire incidents, and endured torture as prisoners of war. Though they are truly heroes, they claim no glory for themselves. As one soldier put it, "When somebody gets decorated, it’s because a lot of other men died."

By at last telling their stories, these men present a hard, unvarnished look at the war on the ground, a final gift from aging warriors who have already given so much. Only with these accounts can the true horror of the war in the Pacific be fully known. Together with detailed maps of each battle, Into the Rising Sun offers a complete yet deeply personal account of the war in the Pacific and a ground-level view of some of history’s most brutal combat.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER ONE

Operation Shoestring

We are the Dead. Short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved and were loved, and now we lie,

In Flanders fields.

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved and were loved, and now we lie,

In Flanders fields.

—COLONEL JOHN MCCRAE ,“IN FLANDERS FIELDS”

ON A CLOUDY AUGUST DAY IN 2001, more than one hundred veterans stood shoulder to shoulder at Arlington National Cemetery. They were there to honor thirteen fellow Marines who were finally returning home—Marines whose bodies had been left behind in a daring 1942 raid on Makin Atoll. After numerous attempts starting in 1948, Army investigators finally found the remains of the men in 1999. The ceremony brought closure to a remarkable chapter in history that had begun almost six decades earlier.

Following the decisive Allied victory at Midway in early June 1942, the Joint Chiefs of Staff, driven primarily by Admiral Ernest King, drew up ambitious plans for offensive operations in the South Pacific. At the time, most of America’s combat troops were being sent to Europe; leftover resources were scarce. Practically no one, including the Japanese, anticipated America on the offensive in the Pacific until 1943.

The Joint Chiefs’ plan had three major tasks: (1) seize Tulagi and adjacent islands in the Solomons, (2) capture the remainder of the Solomons and the northeast coast of New Guinea, and (3) take the huge Japanese anchorage and airdrome on New Britain Island known as Rabaul. Japan’s actions accelerated the Joint Chiefs’ plan. Aerial reconnaissance showed that the Japanese had established a seaplane base at Tulagi and were building a runway on Guadalcanal. Japanese control of the islands threatened the vital sea-lanes between the United States and Australia.1

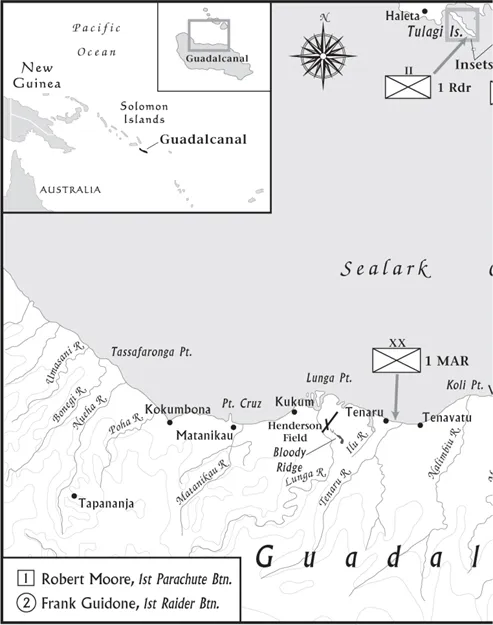

Guadalcanal Landings—August 7–8, 1942

Operation Watchtower was thrown together to quickly land American troops on Guadalcanal and the nearby islands of Tulagi and Gavutu. A basic premise of military planning is that if an attacker is to have any chance of success, he must possess material superiority over the defender. But for Watchtower, the Allies would be outgunned. The situation was so grim that the operation was nicknamed Shoestring. At one point, the theater commander, Admiral Robert Ghormley, became so pessimistic about the viability of the operation that he secretly gave the commander of the 1st Marine Division the authority to surrender.2 Yet Watchtower went forward and eventually encompassed seven major naval battles and scores of air and land battles. The outcome of the campaign was very much in doubt for months.3

It began less than auspiciously, with the understrength 1st Marine Division, which included the elite 1st Raider and 1st Parachute Battalions.4

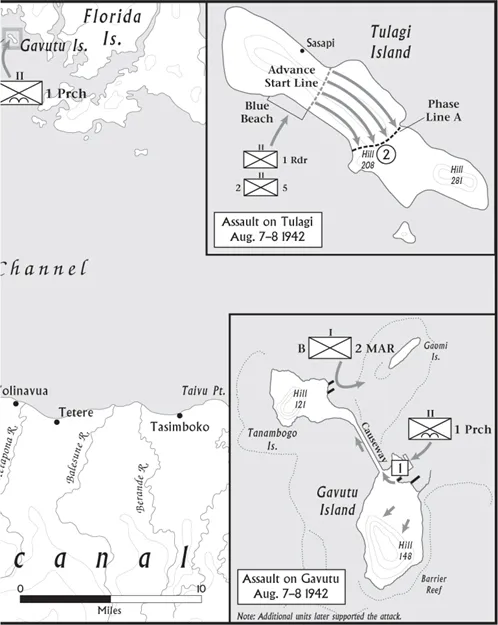

The bulk of America’s invading force, totaling 11,300, landed on Guadalcanal while about 3,000 men commanded by Brigadier General William H. Rupertus were sent to grab several islands north of Guadalcanal: Tulagi, the twin islands of Gavutu-Tanambogo, and portions of Florida Island. The smaller islands of Tulagi, Gavutu, and Tanambogo were considered the operation’s most difficult objectives. Accordingly, Major General Alexander A. Vandegrift assigned these targets to his best-trained units: the Raiders and Marine parachutists. They would get a bitter foretaste of the fighting that faced Americans in the Pacific.

H-hour on Tulagi was 8:00 a.m., August 7, 1942. The 1st Raider Battalion came ashore on the island’s southern coast, designated Blue Beach. The landing was unopposed, and the Raiders were later supported by the 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines. Around noon, they ran into heavy resistance that continued into the night, culminating with several Japanese banzai attacks on the Raider lines. Japanese troops fought to the death from caves and dugouts that had to be blasted with high explosives and grenades. By the next day, Colonel Merritt “Red Mike” Edson, the 1st Raider Battalion commander, declared the island secure. Raider losses were 38 killed and 55 wounded; about 350 defenders were killed, and only 3 prisoners were taken.5

The twin islands of Gavutu-Tanambogo lie 3,000 yards east of Tulagi. On the afternoon of August 7 (H plus four), the 1st Parachute Battalion landed on Gavutu after a brief shore bombardment. The first company met no resistance, but the succeeding waves were raked by fusillades of machine-gun and rifle fire.6 Within minutes, 10 percent of the 397 Marine parachutists were killed or wounded. The surviving paratroopers moved inland, destroying Japanese holed up in caves and seizing the island’s high ground.7 But the island was not yet secure. Tanambogo, connected to Gavutu by a 500-yard causeway, still had to be subdued. General Rupertus sent B Company of the 2nd Marines against Tanambogo. Their initial assault was a disaster. Heavy small-arms fire smashed into B Company’s Higgins boats (landing craft), and the landing was aborted. The company tried again, and this time reached the shore. An additional battalion was brought in, and the island was firmly in Marine hands on August 8. By the end of the operation, more than 20 percent of the paratroopers were killed or wounded, the highest casualty rate of all of the initial landing forces on Guadalcanal.

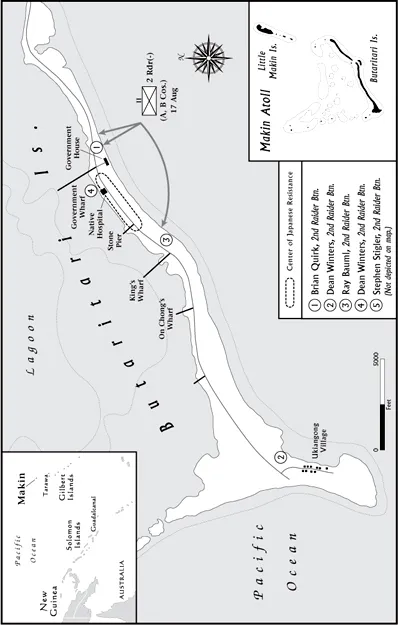

Ten days after the landings at Guadalcanal, A and B Companies of the 2nd Raider Battalion, led by Lieutenant Colonel Evans Carlson, would make one of the most perilous raids of the war. The raid on Makin Atoll, primarily a diversion to lure Japanese attention away from the main landings at Guadalcanal, went badly from the start. The Raiders approached Makin in two submarines, Nautilus and Argonaut. When they surfaced, the men set out for shore in rubber boats in heavy rains and a tumultuous sea. Most of the outboard motors on the boats failed, but the men nevertheless made it ashore.

Shortly after the landing, the Raiders engaged the Japanese garrison in a fierce firefight that included two banzai attacks. Raider casualties began to mount, but the Americans’ attack was more successful than they realized: they had unknowingly killed most of the Japanese on the island.

The Makin Raid—August 17–18, 1942

The Japanese attempted to reinforce Makin by air and sea. Seaplanes carrying reinforcements were destroyed by ground fire, and the submarines managed to sink the boats using indirect fire from their deck guns. But the Japanese retained control of the air. Several enemy planes strafed the Raiders. American plans did not call for holding the island, however; the Raiders were scheduled to assault Little Makin Island the next day. Carlson and his officers (including the battalion executive officer, Major James Roosevelt, the president’s son) agreed to withdraw from the island rather than continue to engage the Japanese.

Withdrawing from Makin was more difficult than invading, however. Outboard motors once again failed to start, and heavy surf capsized many of the boats, keeping many of the Raiders on shore. A few boats made it to the waiting submarines, but Carlson and about 120 men were stranded, most weaponless and weakened from their battle with the sea.

The situation worsened over the next few hours. A Japanese patrol struck the Marines, wounding a sentry. Without working radios to contact the submarines or even knowing whether the subs had survived the air attacks, or if his men had reached them, and believing he was facing a reinforced Japanese force, Carlson called a council of war and decided to surrender.8

Before dawn, the battalion operations officer and another man delivered to a Japanese soldier a note discussing the surrender of the remaining Raiders.9 But the Japanese commanders didn’t get a chance to accept the surrender: the soldier was killed before he could deliver the note to his superiors (Japanese troops found it a few days later, and Tokyo Rose announced the note on Japanese radio).*

By dawn, a few hours after Carlson sent the surrender note, things started to brighten for the Raiders.10 Several men made it through the surf to the subs. Carlson and the subs established contact by flashlight and arranged a rendezvous in the calmer waters off the island’s lagoon. After lashing several boats to a native outrigger, the men paddled out into the lagoon, meeting the subs about 11:00 p.m. Only when the Raiders returned to Pearl Harbor could they get an accurate head count, listing eighteen as killed in action and twelve as missing. And only after the war did the Raiders learn what had happened to some of those men. Nine lost their way during the evacuation. After evading capture for twelve days with the help of some natives, they surrendered on August 30 and were eventually beheaded by the Japanese on Kwajalein Island.

ROBERT MOORE

1ST PARACHUTE BATTALION

Four hours behind the main landings on Guadalcanal and Tulagi, the 1st Parachute Battalion made America’s first contested assault landing of the war on the tiny island of Gavutu. Robert Moore recalls the operation.

As we approached the island, we were raked by machine-gun fire—men were dropping all around me. We had to wade through water up to our necks. I finally got to the beach, and we were held down under heavy fire at the seawall there. I was a BAR [Browning automatic rifle] man, and when I pulled the trigger on my BAR, the damn thing didn’t fire. My platoon leader was Warrant Officer Robert Manning, and he said, “Throw it away!” and gave me a .45 pistol and said, “Stay close!” Anyway, we were under fire all the way in. We tried to go up the hill to some kind of building. On our way up, one of our planes dropped a bomb, causing several friendly casualties.

When we finally got to the top of the hill, one kid was all upset because his buddy from the same town was killed. The buddy had just made second lieutenant and had been killed in the landing. He went up and fired into and beat several bodies to a bloody pulp with his weapon. I don’t know if they were dead or not. We continued clearing out Japanese bunkers and caves.

There was only supposed to be a couple of hundred Japs on the island, and part of them were supposed to be construction troops. We found out later there were many more, including Japanese marines. They were six feet or so—big guys. There were hardly any survivors. We only took a few prisoners.

That night it was raining very hard. It was raining all night. You know when your hands wrinkle after you’ve been in the bathtub too long? That’s how we were the next morning. We assembled and got everyone together. Instead of thirty-six men, we had enough men to make one squad of about twelve men. That morning, my first sergeant called me. It was in my records that I had graduated from embalming college before I went into the Marine Corps, so he elected me to go and take the dog tags off of the dead on the beach. It had never bothered me seeing dead people I hadn’t known, but when you see your buddies there with their heads blown open [chokes up]...it’s a different story.

Over thirty were dead. Many had been shot in the head. Brains were all over [sigh]. I remember Johnny Johns; he was a rigger [parachute maintenance], a real nice fellow. He was in sort of a ditch, shot in the head, brains all over the place. I’ll never forget this. How can you for-get it?

After Gavutu, I was badly wounded on Guadalcanal, sent home, and discharged from the Corps. I recovered and tried to reenlist in the Corps, but I was turned down for medical reasons so I joined the Merchant Marine. Our ship served in the Pacific. One of my shipmates had a neighbor that was killed on Iwo Jima. In December 1945, our ship stopped on Iwo, and I accompanied my shipmate to the cemetery. As you entered the cemetery, they had pieces of old planes—propellers, wings, rocks that had names etched into them. I noticed parachute symbols etched into these crosses and Stars of David. I started going down the roster, and it included most of the men I served with in the 1st Battalion. I was one of the very few that survived. So I found a quiet place and cried. I still cry about it.

FRANK GUIDONE

1ST RAIDER BATTALION

On August 7, the 1st Raider Battalion assaulted Tulagi. The landing was unopposed, but by noon the Raiders were heavily engaged fighting the veteran rikusentai (Japanese elite troops) of the 3rd Kure Special Naval Landing Force. That night, the rikusentai struck A Company, as Frank Guidone, then a squad leader, remembers.

We encountered light action until we got to this one ridge, which was kind of a take-off point. We spread out and formed a skirmish line on the slope of the ridge, and the order came down: “Move out.” The Japanese opened up with their machine guns. It was at this time that we lost two men in our squad. They were Louie Lovin and Leonard Butts. Louie was my BAR man. They both died later of their wounds. Butts died while being treated on a hospital ship and was buried at sea. The squad and I took the news of their death hard. They were family.

A chaplain prepares crosses for Marines killed on Tulagi. (U.S. Navy)

As we moved forward, we were on the same ground as the Japanese, but they were about two or three hundred yards ahead of us. Every once in a while, we’d see them pop up and take a shot or two. After we got down there, I couldn’t advance because I had nobody on my right or left flank. The other platoons got orders to pull back, so we were on our own. Al Belfield, one of my riflemen, was wounded while we were moving ahead. He was wounded in his right upper arm and bled profusely until we applied a tourniquet. They ordered us back up to the high ground. I reported to Captain Antonelli, my company commander. He had a lieutenant escort me to a gap in our line, where I assigned members of my squad to their area of responsibility. We didn’t have time to dig foxholes. We just threw our packs down and got behind them and put our rifles up on our packs and waited. Fires burning below us lighted up the skyline, giving an eerie look to the whole area.

Just after dusk, they started to attack, crawling over the ridge. You could look over the ridgeline, and you could see these forms crawling. That’s when we started throwing our first grenades. We threw grenades all night. Then we heard them yelling at each other and then the moaning. It went on all night long. The closest they got to us was about twenty yards from our line.

At daybreak we heard a rooster crow. Man, that was a good sign. We knew that daylight was coming. It was gray and kept getting lighter. As I looked out toward the ridgetop, I couldn’t believe what I was seeing. There were about twenty-five to thirty Japs piled up. They were slaughtered. We threw about two cases of grenades that night—easily. One Jap was still alive. He got up and started running and got picked off; he didn’t get very far. Later that morning, I went back to the CP [command post] area. I knew this was for real when I noted seven or eight bodies under ponchos—they were in a row. Gif...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Contents

- Introduction

- Overview: The Elite Infantry of the Pacific

- Chapter One: Operation Shoestring

- Chapter Two: Starvation Island: Guadalcanal

- Chapter Three: Up the Solomons: Strangling Rabaul

- Chapter Four: Burma: Merrill’s Marauders

- Chapter Five: New Guinea

- Chapter Six: Into the Marianas

- Chapter Seven: Leyte: The Return to the Philippines

- Chapter Eight: Luzon

- Chapter Nine: Clearing the Philippines: Corregidor, Luzon, and Negros

- Chapter Ten: Into the Jaws of Hell: Iwo Jima

- Chapter Eleven: The Last Battle: Okinawa

- Chapter Twelve: Home

- Appendix

- Notes

- Acknowledgments

- Index

- About the Author

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Into the Rising Sun by Patrick K. O'Donnell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.