- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

One of the twentieth century’s most extraordinary Americans, Pearl Buck was the first person to make China accessible to the West.

She recreated the lives of ordinary Chinese people in The Good Earth, an overnight worldwide bestseller in 1932, later a blockbuster movie. Buck went on to become the first American woman to win the Nobel Prize for Literature. Long before anyone else, she foresaw China’s future as a superpower, and she recognized the crucial importance for both countries of China’s building a relationship with the United States. As a teenager she had witnessed the first stirrings of Chinese revolution, and as a young woman she narrowly escaped being killed in the deadly struggle between Chinese Nationalists and the newly formed Communist Party.

Pearl grew up in an imperial China unchanged for thousands of years. She was the child of American missionaries, but she spoke Chinese before she learned English, and her friends were the children of Chinese farmers. She took it for granted that she was Chinese herself until she was eight years old, when the terrorist uprising known as the Boxer Rebellion forced her family to flee for their lives. It was the first of many desperate flights. Flood, famine, drought, bandits, and war formed the background of Pearl’s life in China. "Asia was the real, the actual world," she said, "and my own country became the dreamworld."

Pearl wrote about the realities of the only world she knew in The Good Earth. It was one of the last things she did before being finally forced out of China to settle for the first time in the United States. She was unknown and penniless with a failed marriage behind her, a disabled child to support, no prospects, and no way of telling that The Good Earth would sell tens of millions of copies. It transfixed a whole generation of readers just as Jung Chang’s Wild Swans would do more than half a century later. No Westerner had ever written anything like this before, and no Chinese had either.

Buck was the forerunner of a wave of Chinese Americans from Maxine Hong Kingston to Amy Tan. Until their books began coming out in the last few decades, her novels were unique in that they spoke for ordinary Asian people— "translating my parents to me," said Hong Kingston, "and giving me our ancestry and our habitation." As a phenomenally successful writer and civil-rights campaigner, Buck did more than anyone else in her lifetime to change Western perceptions of China. In a world with its eyes trained on China today, she has much to tell us about what lies behind its astonishing reawakening.

She recreated the lives of ordinary Chinese people in The Good Earth, an overnight worldwide bestseller in 1932, later a blockbuster movie. Buck went on to become the first American woman to win the Nobel Prize for Literature. Long before anyone else, she foresaw China’s future as a superpower, and she recognized the crucial importance for both countries of China’s building a relationship with the United States. As a teenager she had witnessed the first stirrings of Chinese revolution, and as a young woman she narrowly escaped being killed in the deadly struggle between Chinese Nationalists and the newly formed Communist Party.

Pearl grew up in an imperial China unchanged for thousands of years. She was the child of American missionaries, but she spoke Chinese before she learned English, and her friends were the children of Chinese farmers. She took it for granted that she was Chinese herself until she was eight years old, when the terrorist uprising known as the Boxer Rebellion forced her family to flee for their lives. It was the first of many desperate flights. Flood, famine, drought, bandits, and war formed the background of Pearl’s life in China. "Asia was the real, the actual world," she said, "and my own country became the dreamworld."

Pearl wrote about the realities of the only world she knew in The Good Earth. It was one of the last things she did before being finally forced out of China to settle for the first time in the United States. She was unknown and penniless with a failed marriage behind her, a disabled child to support, no prospects, and no way of telling that The Good Earth would sell tens of millions of copies. It transfixed a whole generation of readers just as Jung Chang’s Wild Swans would do more than half a century later. No Westerner had ever written anything like this before, and no Chinese had either.

Buck was the forerunner of a wave of Chinese Americans from Maxine Hong Kingston to Amy Tan. Until their books began coming out in the last few decades, her novels were unique in that they spoke for ordinary Asian people— "translating my parents to me," said Hong Kingston, "and giving me our ancestry and our habitation." As a phenomenally successful writer and civil-rights campaigner, Buck did more than anyone else in her lifetime to change Western perceptions of China. In a world with its eyes trained on China today, she has much to tell us about what lies behind its astonishing reawakening.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

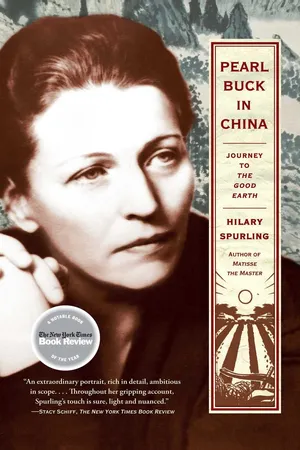

Yes, you can access Pearl Buck in China by Hilary Spurling in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Historical Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Family of Ghosts

PEARL SYDENSTRICKER WAS born into a family of ghosts. She was the fifth of seven children and, when she looked back afterward at her beginnings, she remembered a crowd of brothers and sisters at home, tagging after their mother, listening to her sing, and begging her to tell stories. “We looked out over the paddy fields and the thatched roofs of the farmers in the valley, and in the distance a slender pagoda seemed to hang against the bamboo on a hillside,” Pearl wrote, describing a storytelling session on the veranda of the family house above the Yangtse River. “But we saw none of these.” What they saw was America, a strange, dreamlike, alien homeland where they had never set foot. The siblings who surrounded Pearl in these early memories were dreamlike as well. Her older sisters, Maude and Edith, and her brother Arthur had all died young in the course of six years from dysentery, cholera, and malaria, respectively. Edgar, the oldest, ten years of age when Pearl was born, stayed long enough to teach her to walk, but a year or two later he was gone too (sent back to be educated in the United States, he would be a young man of twenty before his sister saw him again). He left behind a new baby brother to take his place, and when she needed company of her own age, Pearl peopled the house with her dead siblings. “These three who came before I was born, and went away too soon, somehow seemed alive to me,” she said.

Every Chinese family had its own quarrelsome, mischievous ghosts who could be appealed to, appeased, or comforted with paper people, houses, and toys. As a small child lying awake in bed at night, Pearl grew up listening to the cries of women on the street outside calling back the spirits of their dead or dying babies. In some ways she herself was more Chinese than American. “I spoke Chinese first, and more easily,” she said. “If America was for dreaming about, the world in which I lived was Asia…. I did not consider myself a white person in those days.” Her friends called her Zhenzhu (Chinese for Pearl) and treated her as one of themselves. She slipped in and out of their houses, listening to their mothers and aunts talk so frankly and in such detail about their problems that Pearl sometimes felt it was her missionary parents, not herself, who needed protecting from the realities of death, sex, and violence.

She was an enthusiastic participant in local funerals on the hill outside the walled compound of her parents’ house: large, noisy, convivial affairs where everyone had a good time. Pearl joined in as soon as the party got going with people killing cocks, burning paper money, and gossiping about foreigners making malaria pills out of babies’ eyes. “‘Everything you say is lies,’ I remarked pleasantly…. There was always a moment of stunned silence. Did they or did they not understand what I had said? they asked each other. They understood, but could not believe they had.” The unexpected apparition of a small American girl squatting in the grass and talking intelligibly, unlike other Westerners, seemed magical, if not demonic. Once an old woman shrieked aloud, convinced she was about to die now that she could understand the language of foreign devils. Pearl made the most of the effect she produced, and of the endless questions—about her clothes, her coloring, her parents, the way they lived and the food they ate—that followed as soon as the mourners got over their shock. She said she first realized there was something wrong with her at New Year 1897, when she was four and a half years old, with blue eyes and thick yellow hair that had grown too long to fit inside a new red cap trimmed with gold Buddhas. “Why must we hide it?” she asked her Chinese nurse, who explained that black was the only normal color for hair and eyes. (“It doesn’t look human, this hair.”)

Pearl escaped through the back gate to run free on the grasslands thickly dotted with tall pointed graves behind the house. She and her companions, real or imaginary, climbed up and slid down the grave mounds or flew paper kites from the top. “Here in the green shadows we played jungles one day and housekeeping the next.” She was baffled by a newly arrived American, one of her parents’ visitors, who complained that the Sydenstrickers lived in a graveyard. (“That huge empire is one mighty cemetery,” Mark Twain wrote of China, “ridged and wrinkled from its center to its circumference with graves.”) Ancestors and their coffins were part of the landscape of Pearl’s childhood. The big heavy wooden coffins that stood ready for their occupants in her friends’ houses, or lay awaiting burial for weeks or months in the fields and along the canal banks, were a source of pride and satisfaction to farmers whose families had for centuries poured their sweat, their waste, and their dead bodies back into the same patch of soil.

Sometimes Pearl found bones lying in the grass, fragments of limbs, mutilated hands, once a head and shoulder with parts of an arm still attached. They were so tiny she knew they belonged to dead babies, nearly always girls suffocated or strangled at birth and left out for dogs to devour. It never occurred to her to say anything to anybody. Instead she controlled her revulsion and buried what she found according to rites of her own invention, poking the grim shreds and scraps into cracks in existing graves or scratching new ones out of the ground. Where other little girls constructed mud pies, Pearl made miniature grave mounds, patting down the sides and decorating them with flowers or pebbles. She carried a string bag for collecting human remains, and a sharpened stick or a club made from split bamboo with a stone fixed into it to drive the dogs away. She could never tell her mother why she hated packs of scavenging dogs, any more than she could explain her compulsion, acquired early from Chinese friends, to run away and hide whenever she saw a soldier coming down the road.

Soldiers from the hill fort with earthen ramparts above the town were generally indistinguishable from bandits, who lived by rape and plunder. The local warlords who ruled China largely unchecked by a weak central government were always eager to extend or consolidate territory. Severed heads were still stuck up on the gates of walled towns like Zhenjiang, where the Sydenstrickers lived. Life in the countryside was not essentially different from the history plays Pearl saw performed in temple courtyards by bands of traveling actors, or the stories she heard from professional storytellers and anyone else she could persuade to tell them. The Sydenstrickers’ cook, who had the mobile features and expressive body language of a Chinese Fred Astaire, entertained the gateman, the amah, and Pearl herself with episodes from a small private library of books only he knew how to read. This was her first introduction to the old Chinese novels—The White Snake, The Dream of the Red Chamber, All Men Are Brothers—that she would draw on long afterward for the narrative grip, strong plot lines, and stylized characterizations of her own fiction.

Wang Amah, Pearl’s nurse, had an inexhaustible fund of tales of demons and spirits that lived in clouds, rocks, and trees, sea dragons, storm dragons, and the captive local dragon pinned underneath the pagoda on the far hill, who lay in wait for a chance to squirm free, swamp the river, and drown the whole valley. They inhabited an ancient fairyland of spells, charms, incantations, sensational flights, and fights with “wonderful daggers that a man could make small enough to hide in his ear or in the corner of his eye but which, when he fetched them out again, were long and keen and swift to kill.” But even as a small child Pearl liked her fairy stories more closely rooted in reality, and she pestered Wang Amah to tell her about when she was little and how she grew up into a flawless young beauty with pale porcelain skin, plucked forehead, black braided hair that hung to her knees, and three-inch-long bound feet, so lovely that she had to be married off early for fear of predatory soldiers. By the time Pearl knew her thirty or forty years later, Wang Amah was wrinkled and practically toothless (the heartless little Sydenstrickers laughed when she knocked out all but two of her remaining teeth in a fall on the cellar steps), with scanty hair, heavy flaps of skin over her eyes, and a protruding lower lip. She was strict but kind and dependable, a source of warmth and reassurance, the only person in Pearl’s household who ever gave her a hug or took the child onto her lap and into her bed for comfort.

She had been the daughter of a small tradesman in Yangzhou with a prosperous business destroyed in the seismic upheavals all over China that left at least twenty million people dead after the Taiping Rebellion. Wang Amah lost her family—parents, parents-in-law, husband—and with them her means of subsistence. She scraped out a living in the sex trade until hired by Pearl’s mother to look after her children (an appointment badly received by the rest of the mission community). The traumas of her youth resurfaced in her new life as a sequence of thrilling set pieces, starting with her miraculous escape, when she was lowered on a rope down a dry well to save her from Taiping marauders, and going on to the firing of the great pagoda in her hometown, which was burned to the ground with all its priests inside it. Interrogated by Pearl about the smell of roasting men and whether the Chinese variety smelled different from white flesh, Wang Amah replied confidently that white meat was coarser, more tasteless and watery, “because you wash yourselves so much.”

Even the dire process of having her feet bound became heroic in retrospect. Wang Amah explained that her father made her sleep alone in the kitchen outhouse from the age of three so as not to disturb the rest of the family by her crying at night. Rarely able to resist Pearl’s coaxing, she took off the cloth shoes, white stockings, and bandages that had to be worn, even in bed, by women with the infinitely desirable “golden-lily” feet that enforced subjugation as effectively as a ball and chain. Pearl inspected the lump of mashed bone and livid discolored flesh made from forcing together the heel and toes under the instep, leaving only the big toe intact. She had witnessed the mothers of her contemporaries crippling their own daughters’ feet and even suspected she might have ruined her chances of getting a husband by failing to go through the procedure herself. She watched her nurse put the bindings back on without comment. It was one of her first lessons in the power of the imagination to cover up or contain and make bearable things too ugly to confront directly. It was the same lesson she learned from the body parts she found on the hillside. The potent spell Pearl cast later, as a phenomenally successful writer of romantic best sellers, came in large part from this sense of a harsh hidden reality, protruding occasionally but more often invisible, present only beneath the surface of her writing as an unexamined residue of pain and fear.

The second major storyteller of Pearl’s early years was her mother, whose repertoire transported her children to “a place called Home where apples lay on clean grass under the trees, and berries grew on bushes ready to eat, and yards were un-walled and water clean enough to drink without boiling and filtering.” In the enchanted idyll of her mother’s West Virginia childhood, America lay open and free, untouched by the taint of disease, corruption, injustice, or want. (“I grew up misinformed,” Pearl wrote dryly, “and ripe for some disillusionment later.”) The family were Dutch immigrants who had ended up a decade before the Civil War in a small settlement sixty miles west of the Shenandoah Valley, a corridor that allowed Confederate forces to launch raids on Washington from one end and move supplies into Richmond through the other, fought over with relentless ferocity for four years until victorious Federal troops finally laid waste the valley, destroying buildings, slaughtering livestock, and burning crops. Five years old when the war began, Pearl’s mother grew up in a borderland repeatedly occupied by the scavenging, sometimes starving armies of both sides. Like Wang Amah, she reorganized her memories in later life into broad-brush narrative paintings depicting sudden dramatic reversals and hair’s-breadth escapes, with streams of galloping gray and blue cavalry superimposed on the pagoda and the groves of bamboo her listeners could see beyond the veranda.

She applied the same bold graphic technique to her early experiences in China. Caroline Sydenstricker had set sail for the Orient as an idealistic young bride with only the haziest notion about what a missionary career might entail. For her it turned out in practice to mean housekeeping and child rearing in cramped, inconvenient lodgings in the poorer quarters of the more or less hostile cities where her husband parked his growing family, while he himself pushed forward into unknown territory in search of fresh converts. He drove himself on by totting up the staggering totals of heathen sinners to be saved and the pitifully thin line of men like himself standing between them and damnation, an insoluble equation that appalled and maddened him to the end of his life. When the Sydenstrickers first landed in Shanghai to join the Southern Presbyterian Mission in the autumn of 1880, they brought its numbers in the field up to twelve. Apart from a handful of foreign compounds in or near the main trading ports, the interior of China seemed to be theirs for the taking. Seven years later Absalom Sydenstricker persuaded the Mission Board to let him launch a personal assault on the vast, densely populated area of North Kiangsu, setting up his campaign headquarters in the walled city of Tsingkiangpu, nearly three hundred miles north of Shanghai on the Grand Canal, where no missionary had ever settled before. “He had to himself an area as large as the state of Texas, full of souls who had never heard the Gospel,” his daughter wrote later. “He was intoxicated with the magnificence of his opportunity.” The local people received him with passive and often active resistance. A younger colleague eventually dispatched to join him boasted that for three years he made not a single convert, coming home from country trips with spit on his clothes and bruises all over his body from sticks and stones hurled as he passed. Almost overwhelmed by the numerical odds stacked against him, Absalom spent more and more time on the road.

His wife had long ago learned to manage without him. One of the thrilling stories she told her children later was about the night she faced down a mob of farmers with knives and cudgels, who blamed an unprecedented drought on malevolent local gods provoked beyond bearing by the presence of foreign intruders. This was the sweltering hot August of 1889, when rice seedlings withered in the parched fields around Tsingkiangpu. Alerted by men beneath her window plotting in whispers to kill her, Carie found herself alone with Wang Amah and the children (by this stage there were three: eight-year-old Edgar, four-year-old Edith, and the baby Arthur, age seven months), surrounded by an angry populace, a hundred miles from the nearest white outpost, with no one to turn to and no time to send a runner for her absent husband. Her response was to stage a tea party, sweeping the floor, baking cakes, and laying out her best cups and plates. When her uninvited guests arrived at dead of night they found the door flung wide on a lamplit American dream of home-sweet-home, with the three small children waked from sleep and playing peacefully at their mother’s knee. This preposterous story passed into family legend, along with its triumphant outcome: the hard heart of the ringleader was so touched by the spectacle laid on for him that he repented of his murderous mission, accepted a cup of tea instead, and left with his men shortly afterward, only to find rain falling as if by magic later that very same night.

This and similar incidents became part of a folkloric family epic, whose episodes were conflated, transposed, and repeated so often that Pearl, and in due course her younger sister, Grace, knew them and their punch lines by heart. The same stories figure in accounts published later by both sisters, where their mother’s courage, resourcefulness, and determination stand out, burnished to a high gloss against a dull undertow of futility and waste, unfulfilled ambition, stifled hope and desire. There were other stories Carie knew but didn’t tell. At Tsingkiangpu she set up one of a succession of informal clinics for women, where she taught young girls to read and offered sympathy and practical advice to their mothers. Even before they were old enough to understand what was said, her children could hear the urgent, uneven monotone of Chinese women explaining their problems to Carie. Pearl said it was a first-rate novelist’s training.

As a public figure in the second half of her life, Pearl campaigned tirelessly for what were then unfashionable causes: women’s rights, civil rights, black rights, the rights of disabled children and the abandoned children of mixed-race parents. As a writer she would return again and again to her mother’s story, telling and retelling it from different angles in her various memoirs and in the biographies she wrote of each of her parents. Her analysis of Carie’s predicament in The Exile and elsewhere is searching, frank, and perceptive. But it is in the daughter’s fiction that the mother’s voice echoes most insistently between the lines, at times muted, plaintive, and resigned, at others angry and vengeful. In her sixties Pearl published a lurid little novel called Voices in the House about a prime fantasist, a brilliantly precocious and imaginative child who might have grown up to be a novelist herself but descends instead into gruesome madness and murder. All the other characters in the novel are lifeless and bland compared to this energetic self-projection at its core. Voices is the book in which the author said her “two selves” finally merged, meaning not just her American side and her Chinese side, but also her outer and inner selves, reason and instinct, the two aspects of her own personality embodied in the cool, c...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Map

- Foreword: Burying the Bones

- Chapter 1: Family of Ghosts

- Chapter 2: Mental Bifocals

- Chapter 3: The Spirit and the Flesh

- Chapter 4: Inside the Doll’s House

- Chapter 5: Thinking in Chinese

- Chapter 6: In the Mirror of Her Fiction

- Chapter 7: The Stink of Condescension

- Postscript: Paper People

- Sources and Acknowledgments

- Key to Sources

- Notes

- Note on Transliteration

- Index

- Photo Insert

- Back Cover