![]()

PART I

WAR

![]()

CHAPTER 1

Ten Pesos

… Soldierman, sailorman and pioneer

Get yourself a girl and a bottle too,

Blind yourself, hide yourself, the storm is near.

SATURDAY, DECEMBER 6–MONDAY, DECEMBER 8, 1941

Nichols Field, Luzon, Philippine Islands

It was late morning on Saturday, December 6, when they began filing into the post theater at Nichols Field, an American procession of sunglasses, swagger, Vitalis, and lit cigarettes with the brass insignia of Army Air Forces pilots, winged propellers, pinned to their collars.

An assortment of accents, body types, and backgrounds, the fifty-odd pilots of the 17th and 21st Pursuit Squadrons assembled in uniform fashion: clean khaki, college rings, and lieutenant’s bars, with overseas and crush caps perched rakishly on their heads. They carried photographs of their wives and sweethearts in their wallets, but each shared the same, seductive mistress: a love of flying. That love, as well as an appetite for adventure and a sense of duty, had brought them from all corners of the United States to this USAAF base in the Philippines. The 1939 Hollywood blockbuster Gone With the Wind was currently playing in the theater, but the lights did not dim on this warm, peaceful Philippine morning. These pilots were not here to see Clark Gable and Vivien Leigh.

With crossed arms, Col. Harold H. “Pursuit” George waited for stragglers to take seats. George, the forty-nine-year-old chief of staff of the Far East Air Force’s 5th Interceptor Command, was a short, bespectacled, and brilliant officer with a magnetic personality. A decorated pilot in the Great War, he had piercing black eyes. Through the lazy gray haze of curling cigarette smoke, George made a sweeping reconnaissance of the room. Chatter ceased. Zippo lighters snapped shut with a clink. Pursuit George, as was his way, got to the point.

“Men, you are not a suicide squadron yet, but you’re damned close to it,” he said. “There will be war with Japan in a very few days. It may come in a matter of hours.”

George paused. The monotonous drone of airplane motors on testing blocks filled the dewy tropical air. Leather soles nervously scraped the floor.

“The Japs have a minimum of 3,000 planes they can send down on us from Formosa and from aircraft carriers. They know the way already. When they come again, they will be tossing something.”

There was church silence. None of the pilots, most of whom were rookies in their early twenties, had seen aerial combat. But George’s bombshell had not caught 1st Lt. Ed Dyess by surprise. Dyess, the twenty-five-year-old commanding officer of the 21st Pursuit, had watched the winds of war whip the wind sock at San Francisco’s Hamilton Field and for months had worked and prayed that his raw outfit would be ready. The odds, however, had been stacked against him long before he had descended the gangplank from the President Coolidge to Pier 7 in Manila back on November 20, 1941.

According to Japan’s militarists, the rising sun of Amaterasu, the ancient goddess of creation, was waking the Yamato race to its destiny. The annexations of Formosa, Korea, and Manchuria, followed by an invasion of China in 1937, signaled Japan’s desire to resurrect the holy mission of Jimmu Tenno—Japan’s first emperor circa 660 b.c.—called hakko ichiu, meaning to forcefully bring “the eight corners of the world under one roof.”

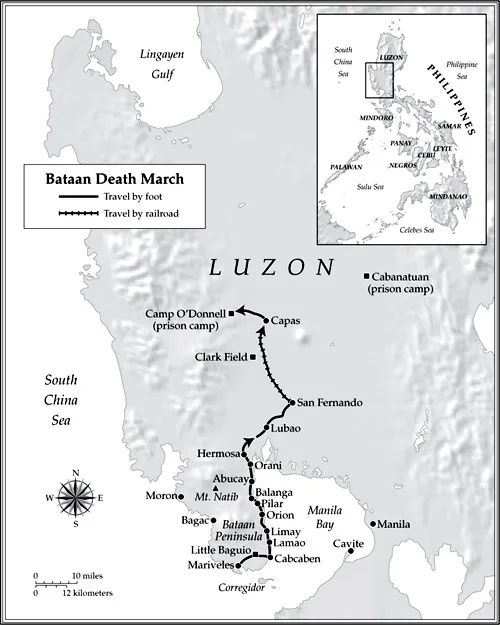

By the summer of 1941, the United States could no longer ignore the gathering Pacific storm. President Franklin D. Roosevelt commenced a diplomatic chess game with Japan, halting exports of American oil, iron, and rubber, freezing Japanese assets in the United States, and closing the Panama Canal to Nippon’s merchant vessels. Roosevelt then looked to America’s most distant ward and its most powerful overseas base, the Philippine Islands, which had been ceded to the United States by Spain after the Spanish-American War. He recalled to active duty sixty-one-year-old Gen. Douglas MacArthur, the former chief of staff, who since 1935 had lived in Manila while serving as military adviser to President Manuel Quezon’s nascent commonwealth government. MacArthur was given command of all forces in the islands, designated USAFFE—United States Army Forces, Far East—but before he could build a Pacific bulwark, he first had to reinvigorate a slumbering command and repair decades of neglect.

The relentless climate—MacArthur called it an “unchanging cocoon of tropical heat”—had gradually suffused the U.S. Army’s Philippine Department in a universal lethargy. There was a five-hour workday, from 0700 to noon. As the mercury rose, men retreated to their billets and barracks, tuned their radios to Stations KZRH, “the Voice of the Orient,” for news and KZRM for big band hits, and took siestas while the blades of electric fans moiled the languorous air. An exchange rate of two Philippine pesos per U.S. dollar ensured that Filipino houseboys kept their bunks neat and their shoes shined, that lavanderas kept their custom-made uniforms and sharkskin suits pressed, and that they could send a few dollars home. Though the islands were rumored to contain a collection of aging and incompetent officers and enlisted eight balls, most were energetic young officers and soldiers using the assignment as either a career springboard or a means to escape the Great Depression.

Poker, baseball, and air-conditioned double features were pastimes for enlisted men; officers golfed or rode their ponies across the Manila Polo Club. At night men from Clark Field and Fort Stotsenburg, the sprawling 150,000-acre U.S. Army complex seventy miles north of Manila in the foothills of the Zambales Mountains, slugged ice-cold bottles of San Miguel beer at the Star Bar while airmen at Nichols Field haunted joints like the Chicago Bar in nearby Parañaque. The real action, however, was found in Manila, a lively hive of culture and commerce abuzz with music from the nightclubs lining Rizal Avenue and the Escolta and aglow with the romantic incandescence of the neon signs advertising the Alhambra Cigar Company and La Insular Cigarettes. Soldiers caught furtive glances from raven-haired Filipinas, drank Tanduay rum, and danced at the Santa Ana Cabaret while sailors drank at the Silver Dollar and staggered out into the sultry night air redolent of jasmine, sewage, and burning incense. Officers mingled with Manila’s social elite in the Jai Alai Building’s Sky Room and debated the football fortunes of West Point and Annapolis at the Army-Navy Club. Any way one looked at it, from an officer’s privileged view or from the vantage point of those in the enlisted ranks, the Philippines seemed a serviceman’s Shangri-la.

But the combat prowess of U.S. troops was unknown. MacArthur also suffered a severe numerical disadvantage: he could oppose Japan’s military might with only the 22,000 troops comprising the U.S. Army’s Philippine Division: the all-American 31st Infantry and two regiments of Philippine Scouts, crack Filipino soldiers serving under U.S. officers. Ten Philippine Army reserve divisions would soon be available, but these troops, noted one observer, knew how to do little else but salute and line up for chow.

The American and Filipino soldiers thus far mustered drilled with brimmed model M1917A1 “doughboy” steel helmets and coconut fiber pith helmets and old Springfield 1903 and Enfield rifles. Glaringly, there were no tanks or armored vehicles in the Philippines. Two years after the bloody slaughter of Polish lancers by German tanks, anachronistic cavalry troops still galloped across the immaculate grounds of Fort Stotsenburg. Hangars throughout the archipelago housed mostly observation planes, obsolete bombers, and pursuit planes. The Asiatic Fleet was still anchored in the past at Cavite, near where Commodore George Dewey’s squadron had sunk the Spanish fleet in 1898, a skeleton force of cruisers, old flush-deck destroyers, submarines, tankers, and PT boats, “a little stick which the United States carried while talking loudly in the Far East,” remarked an Associated Press correspondent.

Inside USAFFE headquarters at No. 1 Callé Victoria in Intramuros, the old Spanish fortress city at the mouth of the Pasig River, MacArthur went to work. He deemed War Plan Orange—a contingency plan developed in the 1920s that called for American forces to withdraw to the Bataan Peninsula and the fortified islands of Manila Bay and wait for the Navy to dispatch the Japanese fleet—“defeatist.” Instead he argued for an aggressive defense of the Philippines. Such a plan, taking into account the sheer size of the Philippines—the archipelago was composed of 7,107 islands and nearly 100,000 square miles of shoreline segmented into the three main island groups: Luzon, the Visayas, and Mindanao—was impractical. Envisioning the Philippines—and himself—as the nexus of America’s military presence in the Pacific, the egotistical commander requested an expansion of his mission in late 1941.

The War Department, viewing the Philippines as, in the words of Secretary of War Henry Stimson, a “strategic opportunity of utmost importance,” would accommodate MacArthur. Stimson and Chief of Staff Gen. George C. Marshall had convinced FDR that with enough time, the islands could become an impregnable stronghold—America’s Singapore. The advent of Rainbow 5, the War Department’s newest plan for a global, multi-theater conflict, illustrated Washington’s commitment. The AAF agreed to ferry thirty-five new B-17 Flying Fortresses, one-third of its existing bomber strength, to the islands, and promised ninety-five more B-17s and B-24 Liberators and 195 brand-new Curtiss P-40B and P-40E Warhawk pursuit planes, as well as fifty-two Douglas A-24 dive bombers, by October 1942. Three radar units were scheduled to be operational by early December. The 4th Marine Regiment would depart Shanghai—where it had been buffering the International Settlement from the Sino-Japanese War—to join antiaircraft, engineer, and tank elements, mostly National Guard units, earmarked for the Philippines. MacArthur was also promised 50,000 Army regulars by February 1942.

Ships were hurriedly discharging their cargoes onto Manila’s crowded wharves, but much of the matériel would never arrive. A shortage of transports had created a backlog of nearly one million tons in U.S. ports by November 1941. The eleventh-hour buildup had accelerated beyond the logistical capacity of America’s war machine, resulting in an epidemic of snafus and shortages that would plague USAFFE throughout the coming campaign. The fledgling Far East Air Force would be affected. Lieutenant Dyess, for example, had arrived with only his crew and thirteen pilots—half of a squadron’s regular complement—and no planes. His first batch of P-40s had finally arrived, unassembled, on December 4, but making the planes combat-ready was another matter. There was hardly any engine coolant or any oxygen for the planes’ high-altitude compressors. Because of a scarcity of ammunition, the wing-mounted .50 caliber machine guns could not be boresighted, despite the hard work crews had put into cleaning the barrels of the greasy, anticorrosive substance called Cosmoline.

Perhaps the most acute shortage affecting USAFFE in late 1941 was that of time. MacArthur thought the chance of offensive action by the Japanese before early 1942 highly unlikely. Not only did he exaggeratedly assure Washington that the training of his Filipino recruits was proceeding ahead of schedule, he also thought that the B-17s would prove an effective deterrent. “The inability of an enemy to launch his air attack on these islands is our greatest security,” he told British Admiral Sir Thomas Phillips during a conference in Manila.

Imperial General Headquarters in Tokyo, however, had its own timetable. An unidentified plane had been discovered over Luzon in the early morning hours of December 4. Throughout the next two days, the oscilloscope of the Air Warning Service’s new SCR-270B radar unit at Iba Field had registered additional blips, bogeys thought to be enemy reconnaissance planes. Since the blips meshed with intelligence reports of Japanese fleet movements, a state of alert was declared. Leaves were suspended and MacArthur ordered his B-17s to the distant safety of Mindanao, but less than half had gone south. The remaining bombers, unpainted, gleaming metallic silver, were scattered about Clark Field.

In the eerie, blacked-out quiet of Manila, tropical tradewinds sighed through palms, diffused fleeting scents of hibiscus and sampaguita across Luneta Park, and fluttered American flags. Months earlier, the “Pearl of the Orient” had been a bustling, multicultural historical intersection where Pan American’s Clipper flying boats skipped across the harbor while the calesa ponies and carabao carts symbolic of a colonial past still traversed the streets. Now, as searchlight beams swept the skies, the city seemed almost devoid of its soul, its future in doubt.

As George’s briefing continued, Ed Dyess surely sensed that war was on the way. It was something for which he had rehearsed his entire young life.

It was hardly a surprise that Ed Dyess chose to fly. A lust for adventure and mobility seemed to be a hereditary trait in the Dyess clan. John Dyess, a Welshman who crossed the Atlantic to stake out land in Georgia in 1733, was the pacesetter for two centuries of westward migration. Dyess’s father, Richard, son of a Confederate Civil War veteran, landed...