- 384 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

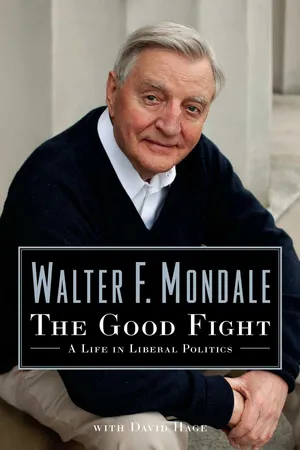

Former vice president Walter Mondale makes a passionate, timely argument for American liberalism in this revealing and momentous political memoir.

For more than five decades in public life, Walter Mondale played a leading role in America’s movement for social change—in civil rights, environmentalism, consumer protection, and women’s rights—and helped to forge the modern Democratic Party.

In The Good Fight, Mondale traces his evolution from a young Minnesota attorney general, whose mentor was Senator Hubert H. Humphrey, into a U.S. senator himself. He was instrumental in pushing President Johnson’s Great Society legislation through Congress and battled for housing equality, against poverty and discrimination, and for more oversight of the FBI and CIA. Mondale’s years as a senator spanned the national turmoil of the Nixon administration; its ultimate self-destruction in the Watergate scandal would change the course of his own political fortunes.

Chosen as running mate for Jimmy Carter’s successful 1976 campaign, Mondale served as vice president for four years. With an office in the White House, he invented the modern vice presidency; his inside look at the Carter administration will fascinate students of American history as he recalls how he and Carter confronted the energy crisis, the Iran hostage crisis, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, and other crucial events, many of which reverberate to the present day.

Carter’s loss to Ronald Reagan in the 1980 election set the stage for Mondale’s own campaign against Reagan in 1984, when he ran with Geraldine Ferraro, the first woman on a major party ticket; this progressive decision would forever change the dynamic of presidential elections.

With the 1992 election of President Clinton, Mondale was named ambassador to Japan. His intriguing memoir ends with his frank assessment of the Bush-Cheney administration and the first two years of the presidency of Barack Obama. Just as indispensably, he charts the evolution of Democratic liberalism from John F. Kennedy to Clinton to Obama while spelling out the principles required to restore the United States as a model of progressive government.

The Good Fight is replete with Mondale’s accounts of the many American political heavyweights he encountered as either an ally or as an opponent, including JFK, Johnson, Humphrey, Nixon, Senator Edward M. Kennedy, the Reverend Jesse Jackson, Senator Gary Hart, Reagan, Clinton, and many others.

Eloquent and engaging, The Good Fight illuminates Mondale’s philosophies on opportunity, governmental accountability, decency in politics, and constitutional democracy, while chronicling the evolution of a man and the country in which he was lucky enough to live.

For more than five decades in public life, Walter Mondale played a leading role in America’s movement for social change—in civil rights, environmentalism, consumer protection, and women’s rights—and helped to forge the modern Democratic Party.

In The Good Fight, Mondale traces his evolution from a young Minnesota attorney general, whose mentor was Senator Hubert H. Humphrey, into a U.S. senator himself. He was instrumental in pushing President Johnson’s Great Society legislation through Congress and battled for housing equality, against poverty and discrimination, and for more oversight of the FBI and CIA. Mondale’s years as a senator spanned the national turmoil of the Nixon administration; its ultimate self-destruction in the Watergate scandal would change the course of his own political fortunes.

Chosen as running mate for Jimmy Carter’s successful 1976 campaign, Mondale served as vice president for four years. With an office in the White House, he invented the modern vice presidency; his inside look at the Carter administration will fascinate students of American history as he recalls how he and Carter confronted the energy crisis, the Iran hostage crisis, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, and other crucial events, many of which reverberate to the present day.

Carter’s loss to Ronald Reagan in the 1980 election set the stage for Mondale’s own campaign against Reagan in 1984, when he ran with Geraldine Ferraro, the first woman on a major party ticket; this progressive decision would forever change the dynamic of presidential elections.

With the 1992 election of President Clinton, Mondale was named ambassador to Japan. His intriguing memoir ends with his frank assessment of the Bush-Cheney administration and the first two years of the presidency of Barack Obama. Just as indispensably, he charts the evolution of Democratic liberalism from John F. Kennedy to Clinton to Obama while spelling out the principles required to restore the United States as a model of progressive government.

The Good Fight is replete with Mondale’s accounts of the many American political heavyweights he encountered as either an ally or as an opponent, including JFK, Johnson, Humphrey, Nixon, Senator Edward M. Kennedy, the Reverend Jesse Jackson, Senator Gary Hart, Reagan, Clinton, and many others.

Eloquent and engaging, The Good Fight illuminates Mondale’s philosophies on opportunity, governmental accountability, decency in politics, and constitutional democracy, while chronicling the evolution of a man and the country in which he was lucky enough to live.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Good Fight by Walter Mondale,David Hage in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Political Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

A Progressive Takes Root

ONE DAY IN the spring of 1962, when I was finishing my second year as Minnesota’s attorney general, I got a phone call from an old friend, Yale Kamisar. He was a law professor at the University of Minnesota and a respected constitutional scholar, and he was calling to ask if I had received a letter from the attorney general of Florida about a states’ rights case that was headed to the U.S. Supreme Court.

I said, “Yes, I just threw it away.”

“Could you fish that out of the wastebasket and tell me what it says?” Kamisar asked. “I think it might be important.” The letter described the case of an indigent Southern drifter who had been arrested on suspicion of burglarizing a pool hall in Florida. He couldn’t afford a lawyer, and at his trial the judge told him Florida law didn’t require the state to provide one except in capital cases. After a brief trial, he was sentenced to five years in prison. From his jail cell he had written the Supreme Court asking the justices to review his case. His name was Clarence Earl Gideon.

At that time I was in touch with several of my counterparts around the country, people such as Tom Eagleton in Missouri, a great friend who later became a wonderful senator, and Eddie McCormack, the attorney general in Massachusetts. It turned out that several states provided counsel to felony defendants, but there was no federal guarantee. In 1942 the Supreme Court had ruled in Betts v. Brady that the Constitution does not flatly require states to furnish counsel. Now Florida’s attorney general, Richard Ervin, was asking his colleagues around the country to support the Betts decision and join the case on his side, arguing that this was a matter of states’ rights. Kamisar, however, felt Betts v. Brady was bad law and thought the Court was ready to reverse itself. He asked me, “Is there any chance you would consider writing a response to Ervin and taking the other side?”

Kamisar’s request made a lot of sense to me. At that time Minnesota already provided counsel to indigent defendants in felony cases, and I thought the due-process argument was clear. But it also appealed to me personally. The idea that a person could be convicted of a serious crime and spend years in jail, even if innocent, purely because he had no money, was an outrage to me. I told Kamisar I was with him, and the next day, with his help, drafted a reply to Ervin:

I believe in federalism and states’ rights too. But I also believe in the Bill of Rights. Nobody knows better than an attorney general or a prosecuting attorney that in this day and age, furnishing an attorney to those felony defendants who can’t afford to hire one is fair and feasible. Nobody knows better than we do that rules of criminal law and procedure which baffle trained professionals can only overwhelm the uninitiated.

Eddie McCormack and I circulated a copy of the letter to every attorney general in the country, while Kamisar began drafting an amicus brief on Gideon’s side. Within weeks attorneys general from twenty-two states had signed on, and we submitted our brief to the U.S. Supreme Court.

In March 1963 the court reversed Betts and handed down a landmark ruling, the Gideon decision, establishing the principle that indigent defendants have a constitutional right to counsel in felony cases. Attorney Abe Fortas, who represented Gideon and later became a Supreme Court justice, cited our work. “We may be comforted in this constitutional moment by the fact that what we are doing has the overwhelming support of the bench, the bar and even of the states.” Justice Hugo Black, writing for the Court, concurred: “Twenty-two states, as friends of the court, argue that Betts was ‘an anachronism when handed down’ and that it should now be overruled. We agree.”

The Gideon brief was probably the most important single case that I pursued in four years as attorney general, and it certainly represented higher stakes than anything a young Minnesota politician expected to handle during his first years in public office. But it typified the era in which I entered politics. A new generation of Democrats was breathing fresh energy into the party’s progressive wing, and people were warming to the view that public office could be used to protect the disadvantaged and advance the rights of ordinary people. Around the country several pivotal figures were transforming the politics of their own states. In Iowa it was Harold Hughes, in Maine it was Ed Muskie, in Wisconsin it was Gaylord Nelson and William Proxmire. In Minnesota, it was Hubert Humphrey.

It was an exciting time, but only later did I grasp how dramatically politics was changing in the Midwest and around the country. In 1946, when I arrived in St. Paul to enroll at Macalester College, Democrats were dead as a political force in Minnesota. Republicans had been running the state for years, and they had the young candidates with talent and energy, people such as Harold Stassen and Elmer L. Andersen. In 1947 Republicans held eight of Minnesota’s nine seats in the U.S. House, and the state hadn’t sent a Democrat to the U.S. Senate for years.

My own politics were still rather vague, even though I had grown up in a household with strong values. My parents, both small-town Midwesterners, loved Franklin Roosevelt and Floyd B. Olson, Minnesota’s great Farmer-Labor governor. My dad, the grandson of Norwegian immigrants, was a Methodist minister who spent his entire career serving small congregations in southern Minnesota. But he read voraciously, subscribed to progressive magazines such as the Nation and the New Republic, and followed the national conversations involving theology and public affairs; my brother, Lester, also a minister, later became a signer of the Humanist Manifesto, an influential document that made a moral case for racial tolerance, internationalism, and an end to poverty. Dad was a gentle man but stern. In my family you got a spanking for two things, bragging and lying, and we never knew which was worse. My mom was remarkable in her own way. She was not of the women’s rights generation, which came later, but she was strong and determined. Having grown up poor in southwestern Minnesota, she somehow gained admission to Northwestern University and earned a music degree. She ran the Sunday school at our church and taught piano lessons to practically every kid in town. In Elmore, they talked about “Mondale weddings,” where my dad presided, my mom played piano, and the Mondale boys sang. After my dad died, she moved to St. Paul and found a job as religious education director at Hamline Methodist Church to support herself and my younger brother Mort. She loved it and the church loved her.

My mom and dad were people of ideas, but they also knew the frustrations and modest hopes of working people in the rural Midwest. My dad had lost a farm in the land crash of the 1920s, and even though he had a series of successful small ministries, we never had a dime. Nevertheless, they tried to expose us to the world beyond the Minnesota prairie. In the summer of 1938, when I was ten, my dad fashioned a makeshift camper out of plywood boards and an old trailer, loaded it with canned goods and a couple of mattresses, and took us to Washington, D.C., for a family vacation. We saw all the sights, but my parents weren’t impressed by the usual tourist attractions. We visited Senator Henry Shipstead of Minnesota; my dad lectured him for abandoning the Farmer-Labor Party, an early force in Minnesota’s progressive politics, to become a Republican. When we left his office, we wandered through the Capitol until we found the marble bust of Senator Robert La Follette, the pioneering Wisconsin progressive. “There,” my dad said, “is a great man.”

For young people such as me, the late 1940s was a period of intellectual testing. Harry Truman was seen as old politics, the machine candidate. Some Democrats were flirting with William O. Douglas and some were still attracted to the Soviet experiment, on the theory that capitalism had failed disastrously in the Great Depression. For a time, I was drawn to Henry Wallace, who ran for president as the Progressive Party candidate in 1948. He was someone my parents admired—he had guts, he campaigned on national health insurance and civil rights, and he had what was probably the first racially integrated campaign in national politics. But then Wallace came to Minnesota for a big rally at the old Minneapolis Armory, and I went to hear him. At that time I had a professor named Huntley Dupre, a Czech-American citizen, who described the way democracy had developed in Czechoslovakia, deep and secure, until it was crushed by the Nazis and then a Soviet-backed Communist takeover. Wallace was campaigning on peace with the Soviets, and that night he defended the Communists by saying Czechoslovakia was having a rightist coup and the Soviets had no choice but to intercede. I left that night thinking, You cannot find common ground with governments that use police-state tactics. This is not where I want to be.

About this time my older brother, Pete, who had attended Macalester ahead of me, mentioned a hotshot political science professor named Hubert Humphrey. By that time Humphrey had left the Macalester faculty and was serving his first term as the young reform mayor of Minneapolis. People on campus still adored him, and one day my political science professor, Dorothy Jacobson, told us that Humphrey was speaking that night in Minneapolis and we should go hear him.

I’ve long since forgotten how I got across town that night, but I will always remember the scene. Humphrey was speaking in a ballroom at the old Dyckman Hotel, and the place was packed. Humphrey was only thirty-five at the time, but he already had a grasp of the big national issues and an intellectual stature that made people take notice. He also had that electrifying speaking style: the machine-gun delivery, the big crescendos, applause lines every few minutes. He hadn’t been speaking more than ten minutes before he had that crowd on fire and the paint blistering off the walls. I remember thinking, This guy is really something.

When Humphrey finished speaking, I introduced myself to his campaign manager, Orville Freeman. Orv was only twenty-eight, but he was a former marine and World War II veteran with a commanding sense of organization. The next thing I knew, I was slogging through the slushy streets of Minneapolis, delivering leaflets and hanging posters for Humphrey’s reelection campaign.

More than a year went by before I saw much of Hubert again. By the summer of 1948 he was running for the Senate, and Freeman had put me in charge of the Second Congressional District in southern Minnesota—my home territory but also a Republican stronghold. That summer the Farm Bureau was holding its annual picnic near Fairmont, Minnesota, and I asked if Humphrey might be their speaker. This was quite a gamble—the Farm Bureau represented the conservative wing of farmer politics—but they hadn’t had a big-name speaker for years and I thought they would be receptive to Humphrey. For his part, Humphrey was eager to get his name known around the state, and I knew he would come to Fairmont if I could raise a big crowd.

The farmers who showed up that day weren’t planning to vote for a Democrat, but within five minutes Hubert had them on their feet cheering. He had that knack for connecting with an audience, understanding what drove them, then speaking right to it. When he was finished, he came over to me and told me I’d done a good job. I was still a kid really, and I drank in every word. “Your work is needed,” he said. “We have so much to do.” After that day, I think I never stopped.

The campaign of 1948 not only launched Humphrey as a national figure, it transformed politics in Minnesota and created the state’s modern reputation for progressive politics. In the 1940s, the state’s Democratic Party was a kind of machine organization, mostly urban and rooted in St. Paul’s Irish immigrant community. If you wanted to be postmaster or get some other patronage position, it was a good organization to join because Roosevelt was president. But it didn’t groom strong candidates, and it wasn’t the place to be if you wanted to win elections. To their left was the United Front crowd—political activists who leaned toward communism. They believed that even though American liberals had our differences with the Soviet Union, we shared the same ideals and could work together. But the Democrats and the United Front had no trust for each other and no issues in common. In fact, in 1944 Franklin Roosevelt feared that Minnesota’s progressive wing would split in two and he would lose the state to a plurality Republican vote. He had heard about Humphrey through Americans for Democratic Action, a progressive, anti-Communist branch of the party that Hubert had cofounded with Eleanor Roosevelt, John Kenneth Galbraith, and Arthur Schlesinger, and he encouraged Humphrey to rebuild the state party.

Hubert was the perfect choice. He was talented and ambitious and had no peer when it came to motivating a crowd. He also knew how to build coalitions. He understood farmers; he could speak their language on issues such as price parity and rural electrification, and he could convince them that he would be their advocate. He did the same thing with the labor movement. He would go over to the Minneapolis Labor Temple every other night and speak to union locals. He understood their goals, too, and he had dozens of ideas to advance the interests of working people. Then he started pulling together all the factions and convincing them that they needed each other to win, and that the old differences and suspicions were only holding them back.

In addition to his political skills, Humphrey had an energy that is hard to appreciate if you never saw him in action. When he was campaigning, he would barnstorm across the state, delivering ten or twelve speeches a day. His driver was Fred Gates, an old friend and longtime supporter, whom Hubert called Pearly Gates because he drove with such abandon. A car would travel ahead of Humphrey from town to town, with a loudspeaker to drum up a crowd, then Hubert would pull in riding in a flatbed truck, and he would speak from the back. Sometimes he would draw only ten or fifteen people, but he didn’t care. When he hit his stride he could stop traffic and bring Main Street to a standstill. (Barry Goldwater, a political rival but personal friend, once described the effect this way: “Hubert has been clocked at 275 words a minute, with gusts up to 340.”) Later, I traveled with Humphrey from time to time, and no matter how tired he was, you could see the color come back into his cheeks and his eyes brighten as he waded into a crowd. He could go for days without showing fatigue. “Don’t spend too much time in bed,” he told me once. “That’s where most people die.”

Because of his political skills and his tremendous energy, Humphrey attracted an entire generation of new talent in his wake. There was Orville, of course, who served three terms as governor and then became U.S. secretary of agriculture. And Gene McCarthy, another political science professor, who became a congressman in 1948 and a senator a decade later. When Humphrey and McCarthy campaigned together, they were unbeatable. There was Gerald Heaney, an accomplished attorney who became a Democratic National Committee member and later a federal judge; Art Naftalin, a brilliant progressive mayor of Minneapolis; and Don Fraser, who was elected to Congress from Minneapolis in 1962 and became a distinguished leader on human rights and foreign policy. They were typical of that generation.

Between 1944 and 1948, Humphrey worked constantly to unify Minnesota’s progressives, finding common ground between farmers and union members, intellectuals and business leaders—while gradually marginalizing the old United Front crowd. The result was the Democratic Farmer-Labor Party, or DFL, which would change the face of Minnesota politics for the next half century. But we got into some pretty rough fights along the way. In early 1948, hoping to earn the party’s nomination for the Senate in November, Humphrey made one last push to consolidate the organization behind him. One of his first moves came at the convention of the Young DFL in Minneapolis. We met at the old Minneapolis Labor Temple. The room was divided right down the middle, the United Front supporters on one side and our group on the other, and you could have cut the tension with a knife. I was afraid we were going to be outnumbered if it came to an endorsement vote, so I brought a big crowd over from the St. Paul college campuses—Macalester, Hamline, and St. Thomas. We packed that place, and I think we caught the other side by surprise. The hard-left people got up and gave their speeches about how we were fascists, then Humphrey got up and brought the crowd to its feet. At one point, someone in the audience asked if he thought the United Front supporters were actually members of the Communist Party. He said, “Well, if they’re not members, they are cheating it out of dues money.” A lot of people in that room had worked with Humphrey in the past, and I think they were stunned at the hard line he took. But he was mesmerizing, and we had the numbers, and he carried the crowd overwhelmingly. At the state convention a month later he did the same thing. He had the numbers and he won the crowd, and after that the party belonged to him.

Some people never forgave Humphrey for what they regarded as a purge of the left in Minnesota politics. But it showed the rest of the party—and voters across the state—that he could be a unifying force, that he represented something new in Minnesota politics and demonstrated that we had an alternative to the Republican Party.

With Humphrey leading the charge, the 1948 election proved to be a turning point in Minnesota’s political history. Humphrey won big, defeating the Republican incumbent, Joe Ball. Truman carried Minnesota, becoming the first Democrat apart from Franklin Roosevelt to carry the state in a presidential race since the Civil War. We elected three new Democrats to Congress, including Gene McCarthy. In a few other races, we just missed. But you could see the elements: a generation of new talent, highly motivated, and the foundation of a new political movement. I packed up my things in Mankato and drove back to St. Paul that night after the polls closed. It was a good feeling. The next morning, Minnesota was a different state.

From time to time around this country, an extraordinary political figure emerges—a candidate who has that unique power of leadership, who breaks the mold and leads his or her state in a fundamentally new direction. In Minnesota, that figure was Humphrey. Minnesota was a cloistered, isolationist place when Humphrey came on the scene in the 1940s; he gave it a worldly, internationalist outlook. It was a state of conservative, self-reliant people. He inspired them to think about social justice and the role government could play in expanding opportunity. He put civil rights on the agenda in a state with a long history of bigotry and anti-Semitism. He brought ambition and a flair for innovation to people who, by nature, were cautious and shy. He didn’t simply establish himself as a leading figure in national politics, he built his state into an admired incubator of progressive ideas. Hubert brought out the decency and optimism in people, and he made Minnesota a different place.

Thirty years later, delivering Humphrey’s eulogy in the rotunda of the U.S. Capitol and reflecting on a friendship that lasted a lifetime, I ventured that Hubert would be remembered as one of the greatest legislators in our history, as one of the most loved men of his time, and even more, as a leader who became his country’s conscience.

After the 1948 election I had to think about my own prospects for a while. When my dad died, we couldn’t afford the tuition at Macalester, so I dropped out and finished my degree at the University of Minnesota. On graduating I joined the army and served two years at Fort Knox, then returned to the Twin Cities and enrolled in law school at the University of Minnesota on the GI Bill. By this time my mom had moved to St. Paul, so I moved in with her and became a full-time law student.

One evening in 1955 a classmate, Bill Canby, invited me over for dinner with his wife, Jane, and her older sister, Joan Adams. I suppose I should have been intimidated: Joan’s father was the chaplain at Macalester College and came from an old Presbyterian family. She had studied history and art, had worked at a museum in Boston, and had an elegance that was quite outside my experience. But she seemed to think it might be all right to date a guy who was getting started in politics. Her mother wasn’t quite so confident. She called one of my professors at Macalester, the great political scientist Theodore Mitau, and asked what sort of young man I was. He told her, Walter doesn’t have much money, but he works hard and I think he has a future. After seven dates in six months, Joan and I were married in the Macalester College chapel.

But all the while, I could not shake the political bug. When Orville Freeman ran for governor in 1950, unsuccessfully, I worked on his campaign. When he ran in 1954, I worked for him again, and this time he won. When he ran for reelection in 1958, I was his campaign manager.

Then one day in the spring of 1960 the phone rang and it was Orv. The attorney general, Miles Lord, was planning to resign, and Freeman wanted to appoint me to fill the vacancy. I was stunned. I had graduated from law school in 1956 and was trying to build a law practice. Joan and I had just bought a house in south Minneapolis. We had one baby, Ted, at home, and our daughter, Eleano...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Introduction: Taking Care

- 1: A Progressive Takes Root

- 2: High Tide

- 3: The Fight for Equality

- 4: Lost Trust: Vietnam and the Election of 1968

- 5: Poverty and Opportunity

- 6: The Battle for a More Responsive Senate

- 7: Spies, Security, and the Rule of Law

- 8: Meeting a New Democrat

- 9: Our First Year in the White House

- 10: Showing the World a Different America

- 11: America in an Age of Limits

- 12: Hostage Crisis

- 13: The Election of 1980

- 14: Mondale vs. Reagan

- 15: An Alliance in Asia

- 16: Looking Forward

- Photo Insert

- Acknowledgments

- Index