eBook - ePub

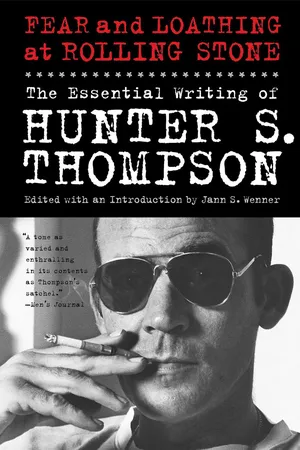

Fear and Loathing at Rolling Stone

The Essential Writing of Hunter S. Thompson

- 592 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Fear and Loathing at Rolling Stone

The Essential Writing of Hunter S. Thompson

About this book

From the bestselling author of The Rum Diary and king of “Gonzo” journalism Hunter S. Thompson, comes the definitive collection of the journalist’s finest work from Rolling Stone. Fear and Loathing at Rolling Stone showcases the roller-coaster of a career at the magazine that was his literary home.

“Buy the ticket, take the ride,” was a favorite slogan of Hunter S. Thompson, and it pretty much defined both his work and his life. Jann S. Wenner, the outlaw journalist’s friend and editor for nearly thirty-five years, has assembled articles—and a wealth of never- before-seen correspondence and internal memos from Hunter’s storied tenure at Rolling Stone—that begin with Thompson’s infamous run for sheriff of Aspen on the Freak Party ticket in 1970 and end with his final piece on the Bush-Kerry showdown of 2004. In between is Thompson’s remarkable coverage of the 1972 presidential campaign and plenty of attention paid to Richard Nixon; encounters with Muhammad Ali, Bill Clinton, and the Super Bowl; and a lengthy excerpt from his acknowledged masterpiece, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. The definitive volume of Hunter S. Thompson’s work published in the magazine, Fear and Loathing at Rolling Stone traces the evolution of a personal and professional relationship that helped redefine modern American journalism, presenting Thompson through a new prism as he pursued his lifelong obsession: The life and death of the American Dream.

“Buy the ticket, take the ride,” was a favorite slogan of Hunter S. Thompson, and it pretty much defined both his work and his life. Jann S. Wenner, the outlaw journalist’s friend and editor for nearly thirty-five years, has assembled articles—and a wealth of never- before-seen correspondence and internal memos from Hunter’s storied tenure at Rolling Stone—that begin with Thompson’s infamous run for sheriff of Aspen on the Freak Party ticket in 1970 and end with his final piece on the Bush-Kerry showdown of 2004. In between is Thompson’s remarkable coverage of the 1972 presidential campaign and plenty of attention paid to Richard Nixon; encounters with Muhammad Ali, Bill Clinton, and the Super Bowl; and a lengthy excerpt from his acknowledged masterpiece, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. The definitive volume of Hunter S. Thompson’s work published in the magazine, Fear and Loathing at Rolling Stone traces the evolution of a personal and professional relationship that helped redefine modern American journalism, presenting Thompson through a new prism as he pursued his lifelong obsession: The life and death of the American Dream.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Fear and Loathing at Rolling Stone by Hunter S. Thompson, Jann Wenner in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Journalist Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Last Tango in Vegas: Fear and Loathing in the Near Room and the Far Room

May 4 and May 18, 1978

When I’m gone, boxing will be nothing again. The fans with the cigars and the hats turned down’ll be there, but no more housewives and little men in the street and foreign presidents. It’s goin’ to be back to the fighter who comes to town, smells a flower, visits a hospital, blows a horn, and says he’s in shape. Old hat. I was the onliest boxer in history people asked questions like a senator.

—Muhammad Ali, 1967

Life had been good to Pat Patterson for so long that he’d almost forgotten what it was like to be anything but a free-riding, first-class passenger on a flight near the top of the world . . .

It is a long, long way from the frostbitten midnight streets around Chicago’s Clark and Division to the deep-rug hallways of the Park Lane Hotel on Central Park South in Manhattan . . . But Patterson had made that trip in high style, with stops along the way in London, Paris, Manila, Kinshasa, Kuala Lumpur, Tokyo, and almost everywhere else in the world on that circuit where the menus list no prices and you need at least three pairs of $100 sunglasses just to cope with the TV lights every time you touch down at an airport for another frenzied press conference and then a ticker-tape parade along the route to the presidential palace and another princely reception.

That is Muhammad Ali’s world, an orbit so high, a circuit so fast and strong and with rarefied air so thin that only “The Champ,” “The Greatest,” and a few close friends have unlimited breathing rights. Anybody who can sell his act for $5 million an hour all over the world is working a vein somewhere between magic and madness . . . And now, on this warm winter night in Manhattan, Pat Patterson was not entirely sure which way the balance was tipping. The main shock had come three weeks ago in Las Vegas, when he’d been forced to sit passively at ringside and watch the man whose life he would gladly have given his own to protect, under any other circumstances, take a savage and wholly unexpected beating in front of five thousand screaming banshees at the Hilton Hotel and something like sixty million stunned spectators on national network TV. The Champ was no longer The Champ: a young brute named Leon Spinks had settled that matter, and not even Muhammad seemed to know just exactly what that awful defeat would mean—for himself or anyone else; not even for his new wife and children, or the handful of friends and advisers who’d been working that high white vein right beside him for so long that they acted and felt like his family.

It was definitely an odd lot, ranging from solemn Black Muslims like Herbert Muhammad, his manager—to shrewd white hipsters like Harold Conrad, his executive spokesman, and Irish Gene Kilroy, Ali’s version of Hamilton Jordan: a sort of all-purpose administrative assistant, logistics manager, and chief troubleshooter. Kilroy and Conrad are The Champ’s answer to Ham and Jody—but mad dogs and wombats will roam the damp streets of Washington, babbling perfect Shakespearean English, before Jimmy Carter comes up with his version of Drew “Bundini” Brown, Ali’s alter ego and court wizard for so long now that he can’t really remember being anything else. Carter’s thin-ice sense of humor would not support the weight of a zany friend like Bundini. It would not even support the far more discreet weight of a court jester like J.F.K.’s Dave Powers, whose role in the White House was much closer to Bundini Brown’s deeply personal friendship with Ali than Jordan’s essentially political and deceptively hard-nosed relationship with Jimmy . . . and even Hamilton seems to be gaining weight by geometric progressions these days, and the time may be just about ripe for him to have a chat with the Holy Ghost and come out as a “bornagain Christian.”

That might make the nut for a while—at least through the 1980 reelection campaign—but not even Jesus could save Jordan from a fate worse than any hell he’d ever imagined if Jimmy Carter woke up one morning and read in the Washington Post that Hamilton had pawned the great presidential seal for $500 in some fashionable Georgetown hockshop . . . or even with one of his good friends like Pat Caddell, who enjoys a keen eye for collateral.

Indeed . . . and this twisted vision would seem almost too bent for print if Bundini hadn’t already raised at least the raw possibility of it by once pawning Muhammad Ali’s “Heavyweight Champion of the World” gold-and-jewel-studded belt for $500—just an overnight loan from a friend, he said later; but the word got out, and Bundini was banished from The Family and the whole entourage for eighteen months when The Champ was told what he’d done.

That heinous transgression is shrouded in a mix of jive-shame and real black humor at this point: The Champ, after all, had once hurled his Olympic gold medal into the Ohio River, in a fit of pique at some alleged racial insult in Louisville—and what was the difference between a gold medal and a jewel-studded belt? They were both symbols of a “white devil” ’s world that Ali, if not Bundini, was already learning to treat with a very calculated measure of public disrespect . . . What they shared, far beyond a very real friendship, was a shrewd kind of street-theater sense of how far out on that limb they could go, without crashing. Bundini has always had a finer sense than anyone else in The Family about where The Champ wanted to go, the shifting winds of his instincts, and he has never been worried about things like Limits or Consequences. That was the province of others, like Conrad or Herbert. Drew B. has always known exactly which side he was on, and so has Cassius/Muhammad. Bundini is the man who came up with “Float like a butterfly. Sting like a bee,” and ever since then he has been as close to both Cassius Clay and Muhammad Ali as anyone else in the world.

Pat Patterson, by contrast, was a virtual newcomer to The Family. A two-hundred-pound, forty-year-old black cop, he was a veteran of the Chicago vice squad before he hired on as Ali’s personal bodyguard. And, despite the total devotion and relentless zeal he brought to his responsibility for protecting The Champ at all times from any kind of danger, hassles, or even minor inconvenience, six years on the job had caused him to understand, however reluctantly, that there were at least a few people who could come and go as they pleased through the wall of absolute security he was supposed to maintain around The Champ.

Bundini and Conrad were two of these. They have been around for so long that they had once called the boss “Cassius,” or even “Cash”—while Patterson had never addressed him as anything but “Muhammad” or “Champ.” He had come aboard at high tide, as it were, and even though he was now in charge of everything from carrying Ali’s money—in a big roll of $100 bills—to protecting his life with an ever-present chrome-plated revolver and the lethal fists and feet of a black belt with a license to kill, it had always galled him a bit to know that Muhammad’s capricious instincts and occasionally perverse sense of humor made it certifiably impossible for any one bodyguard, or even four, to protect him from danger in public. His moods were too unpredictable: one minute he would be in an almost catatonic funk, crouched in the backseat of a black Cadillac limousine with an overcoat over his head—and then, with no warning at all, he would suddenly be out of the car at a red light somewhere in the Bronx, playing stickball in the street with a gang of teenage junkies. Patterson had learned to deal with The Champ’s moods, but he also knew that in any crowd around The Greatest, there would be at least a few who felt the same way about Ali as they had about Malcolm X or Martin Luther King.

There was a time, shortly after his conversion to the Black Muslim religion in the mid-Sixties, when Ali seemed to emerge as a main spokesman for what the Muslims were then perfecting as the State of the Art in racial paranoia—which seemed a bit heavy and not a little naive at the time, but which the White Devils moved quickly to justify . . .

Yes. But that is a very long story, and we will get to it later. The only point we need to deal with right now is that Muhammad Ali somehow emerged from one of the meanest and most shameful ordeals any prominent American has ever endured as one of the few real martyrs of that goddamn wretched war in Vietnam and a sort of instant folk hero all over the world, except in the U.S.A.

That would come later . . .

• • •

The Spinks disaster in Vegas had been a terrible shock to The Family. They had all known it had to come sometime, but the scene had already been set and the papers already signed for that “sometime”—a $16 million purse and a mind-boggling, damn-the-cost television spectacle with Ali’s old nemesis Ken Norton as the bogyman, and one last king-hell payday for everybody. They were prepared, in the back of their hearts, for that one—but not for the cheap torpedo that blew their whole ship out of the water in Vegas for no payday at all. Leon Spinks crippled a whole industry in one hour on that fateful Wednesday evening in Las Vegas—the Muhammad Ali Industry, which has churned out roughly $56 million in over fifteen years and at least twice or three times that much for the people who kept the big engine running all this time. (It would take Bill Walton 112 years on an annual NBA salary of $500,000 to equal that figure.)

I knew it was too close for comfort. I told him to stop fooling around. He was giving up too many rounds. But I heard the decision and I thought, “Well, what are you going to do? That’s it. I’ve prepared myself for this day for a long time. I conditioned myself for it. I was young with him and now I feel old with him.”

—Angelo Dundee, Ali’s trainer

Dundee was not the only person who was feeling old with Muhammad Ali on that cold Wednesday night in Las Vegas. Somewhere around the middle of the fifteenth round, a whole generation went over the hump as the last Great Prince of the Sixties went out in a blizzard of pain, shock, and angry confusion so total that it was hard to even know how to feel, much less what to say, when the thing was finally over. The last shot came just at the final bell, when “Crazy Leon” whacked Ali with a savage overhand right that almost dropped The Champ in his tracks and killed the last glimmer of hope for the patented “miracle finish” that Angelo Dundee knew was his fighter’s only chance. As Muhammad wandered back to his corner about six feet in front of me, the deal had clearly gone down.

The decision was anticlimactic. Leon Spinks, a twenty-four-year-old brawler from St. Louis with only seven professional fights on his record, was the new heavyweight boxing champion of the world. And the roar of the pro-Spinks crowd was the clearest message of all: that uppity nigger from Louisville had finally got what was coming to him. For fifteen long years he had mocked everything they all thought they stood for: changing his name, dodging the draft, beating the best they could hurl at him . . . But now, thank God, they were seeing him finally go down.

Six presidents have lived in the White House in the time of Muhammad Ali. Dwight Eisenhower was still rapping golf balls around the Oval Office when Cassius Clay Jr. won a gold medal for the U.S. as a light-heavyweight in the 1960 Olympics and then turned pro and won his first fight for money against a journeyman heavyweight named Tunney Hunsaker in Louisville on October 29 of that same year.

Less than four years later and almost three months to the day after John Fitzgerald Kennedy was murdered in Dallas, Cassius Clay—the “Louisville Lip” by then—made a permanent enemy of every “boxing expert” in the Western world by beating World Heavyweight Champion Sonny Liston, the meanest of the mean, so badly that Liston refused to come out of his corner for the seventh round.

That was fourteen years ago. Jesus! And it seems like fourteen months.

The Near Room

When he got in trouble in the ring, [Ali] imagined a door swung open and inside he could see neon orange and green lights blinking, and bats blowing trumpets and alligators playing trombones, and he could hear snakes screaming. Weird masks and actors’ clothes hung on the wall, and if he stepped across the sill and reached for them, he knew that he was committing himself to destruction.

—George Plimpton, Shadow Box

It was almost midnight when Pat Patterson got off the elevator and headed down the corridor toward 905, his room right next door to The Champ’s. They had flown in from Chicago a few hours earlier, and Muhammad had said he was tired and felt like sleeping. No midnight strolls down the block to the Plaza fountain, he promised, no wandering around the hotel or causing a scene in the lobby.

Beautiful, thought Patterson. No worries tonight. With Muhammad in bed and Veronica there to watch over him, Pat felt things were under control, and he might even have time for a bit of refreshment downstairs and then get a decent night’s sleep for himself. The only conceivable problem was the volatile presence of Bundini and a friend, who had dropped by around ten for a chat with The Champ about his run for the Triple Crown. The Family had been in a state of collective shock for two weeks or so after Vegas, but now it was the first week in March, and they were eager to get the big engine cranked up for the return bout with Spinks in September. No contracts had been signed yet, and every sportswriter in New York seemed to be on the take from either Ken Norton or Don King or both . . . But none of that mattered, said Ali, because he and Leon had already agreed on the rematch, and by the end of this year he would be the first man in history to win the heavyweight championship of the world three times.

Patterson had left them whooping and laughing at each other, but only after securing a promise from Hal Conrad that he and Bundin...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Foreword by Jann S. Wenner

- Introduction by Paul Scanlon

- The Battle of Aspen: Freak Power in the Rockies

- Strange Rumblings in Aztlan: The Murder of Ruben Salazar

- Memo from the Sports Desk: The So-Called “Jesus Freak” Scare

- Fear & Loathing in Las Vegas: A Savage Journey to the Heart of the American Dream, Part II . . . by Raoul Duke

- The Campaign Trail: Is This Trip Necessary?

- The Campaign Trail: The Million-Pound Shithammer

- The Campaign Trail: Fear and Loathing in New Hampshire

- The Campaign Trail: The View from Key Biscayne

- The Campaign Trail: The Banshee Screams in Florida

- The Campaign Trail: Bad News from Bleak House: Total Failure in Milwaukee . . . with a Few Quick Thoughts on the Shocking Victory of Double-George . . .

- The Campaign Trail: More Late News from Bleak House

- The Campaign Trail: Crank-Time on the Low Road

- The Campaign Trail: Fear and Loathing in California: Traditional Politics with a Vengeance

- The Campaign Trail: In the Eye of the Hurricane

- The Campaign Trail: Fear & Loathing in Miami: Old Bulls Meet the Butcher

- The Campaign Trail: More Fear and Loathing in Miami: Nixon Bites the Bomb

- The Campaign Trail: The Fat City Blues

- Ask Not for Whom the Bell Tolls . . .

- Memo from the Sports Desk & Rude Notes from a Decompression Chamber in Miami

- Fear and Loathing at the Watergate: Mr. Nixon Has Cashed His Check

- Fear and Loathing at the Super Bowl

- Fear and Loathing in Limbo: The Scum Also Rises

- Interdicted Dispatch from the Global Affairs Desk

- Fear & Loathing on the Campaign Trail ’76: Third-Rate Romance, Low-Rent Rendezvous

- Fear & Loathing in the Graveyard of the Weird: The Banshee Screams for Buffalo Meat

- Last Tango in Vegas: Fear and Loathing in the Near Room and the Far Room

- A Dog Took My Place

- The Taming of the Shrew

- Fear and Loathing in Elko

- Mr. Bill’s Neighborhood

- Letter to William Greider

- He Was a Crook

- Polo Is My Life: Fear and Loathing in Horse Country

- Memo from the National Affairs Desk. To: Dollar Bill Greider

- Memo from the National Affairs Desk. To: Jann S. Wenner.

- The Shootist: A Short Tale of Extreme Precision and No Fear

- Memo from the National Affairs Desk: More Trouble in Mr. Bill’s Neighborhood

- Hey Rube! I Love You: Eerie Reflections on Fuel, Madness & Music

- The Fun-Hogs in the Passing Lane

- Postscript: Letter from HST to JSW

- Acknowledgments

- About Hunter S. Thompson

- Copyright