eBook - ePub

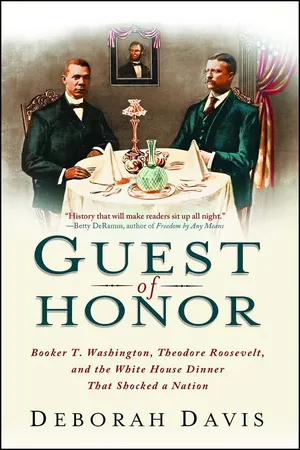

Guest of Honor

Booker T. Washington, Theodore Roosevelt, and the White House Dinner That Shocked a Nation

- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Guest of Honor

Booker T. Washington, Theodore Roosevelt, and the White House Dinner That Shocked a Nation

About this book

In this revealing social history, one remarkable White House dinner becomes a lens through which to examine race, politics, and the lives and legacies of two of America’s most iconic figures.

In 1901, President Theodore Roosevelt invited Booker T. Washington to have dinner at the executive mansion with the First Family. The next morning, news that the president had dined with a black man—and former slave—sent shock waves through the nation. Although African Americans had helped build the White House and had worked for most of the presidents, not a single one had ever been invited to dine there. Fueled by inflammatory newspaper articles, political cartoons, and even vulgar songs, the scandal escalated and threatened to topple two of America’s greatest men.

In this smart, accessible narrative, one seemingly ordinary dinner becomes a window onto post–Civil War American history and politics, and onto the lives of two dynamic men whose experiences and philosophies connect in unexpected ways. Deborah Davis also introduces dozens of other fascinating figures who have previously occupied the margins and footnotes of history, creating a lively and vastly entertaining book that reconfirms her place as one of our most talented popular historians.

In 1901, President Theodore Roosevelt invited Booker T. Washington to have dinner at the executive mansion with the First Family. The next morning, news that the president had dined with a black man—and former slave—sent shock waves through the nation. Although African Americans had helped build the White House and had worked for most of the presidents, not a single one had ever been invited to dine there. Fueled by inflammatory newspaper articles, political cartoons, and even vulgar songs, the scandal escalated and threatened to topple two of America’s greatest men.

In this smart, accessible narrative, one seemingly ordinary dinner becomes a window onto post–Civil War American history and politics, and onto the lives of two dynamic men whose experiences and philosophies connect in unexpected ways. Deborah Davis also introduces dozens of other fascinating figures who have previously occupied the margins and footnotes of history, creating a lively and vastly entertaining book that reconfirms her place as one of our most talented popular historians.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Guest of Honor by Deborah Davis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Political Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

THE BIG HOUSE

Hale’s Ford, Virginia, was “about as near to nowhere as any locality gets to be.” That’s how Booker T. described the rural community in Franklin County where he was born in April 1856, or maybe ’57 or ’58—he was never sure of the year because the records kept by slaves were very sketchy. He wasn’t sure about his father, either, although rumor had it that he was a white man from a nearby plantation, possibly the Hatcher farm or the Ferguson place. His mother, Jane, cooked for her owners, the Burroughs family, and lived with her three children, John, Booker T., and little Amanda, in a broken-down cabin on their property. The floor was dirt, the walls were cracked, and the centerpiece of the dilapidated one-room dwelling was a large pit where the Burroughses stored their sweet potatoes for the winter. There was also a swinging “cat” door for a house pet to use as an entrance and exit, something that always amused Booker T. because there were enough holes in the broken walls to provide full access for a whole litter of cats.

Jane had a husband, a slave named Washington Ferguson who belonged to the Ferguson family next door, but she saw him infrequently because he was hired out on jobs far from home. Whenever he visited, Wash proved to be a hard, unsentimental man with little patience for his two stepsons or his daughter, Amanda. During the Civil War he escaped to West Virginia, where he became a free man. Not that his new life was easy. Wash toiled in the salt mines of the Kanawha Valley and endured long separations from his wife back in Hale’s Ford.

Although Booker T. always referred to the Burroughs home as the “big house,” there was nothing big about it. The word plantation usually evoked images of stately white mansions with Roman columns and sweeping verandas, but Jones and Elizabeth Burroughs and, at various times, some or all of their fourteen children lived in a nondescript, five-room house made of logs. They were working farmers, not Southern aristocrats, and the ten slaves they owned were an investment as well as a source of labor. Each slave had a dollar value. Jane, who was getting on in years, was worth $250, while Booker T., who had a lifetime of work ahead of him, was assessed at $400.

Daily life for Booker T. was defined by what he didn’t have and couldn’t do. He and his siblings never slept in a bed or sat down at a table to share a meal. Instead they ate like “dumb animals,” he later recalled, grabbing “a piece of bread here and a scrap of meat there.” Even kernels of corn that had been overlooked by the pigs were fair game for a hungry boy. Having a mother who was a cook made things worse because she prepared the meals for the “big house” in her own fireplace, and the tantalizing scents of forbidden foods reminded the children of what they were missing. Occasionally Jane would see to it that a bootlegged chicken came their way but, more than anything, Booker T. coveted the ginger cakes he saw his young mistresses serve their visitors. He thought the delicacies, sweet with molasses and fragrant with the exotic scent of ginger, were “the most tempting and desirable things” he had ever seen. Freedom, in his childish imagination, was an unlimited supply of ginger cakes.

Booker T.’s dream was to learn to read. His favorite chore was to escort one of the Burroughs daughters to the Frog Pond Schoolhouse down the road. After she would go inside, he lingered and listened at the window, fascinated by the lessons and recitations he heard. He couldn’t make much sense of it, just enough to know that he wanted to enter this “paradise” and learn more. This was out of the question because teaching a slave to read was against the law in Virginia and everywhere else in the South. Besides, his other chores beckoned. There was corn to deliver to the mill, water to distribute to the field hands, and plenty of cleaning and sweeping.

The job he enjoyed most was fanning the dining room while his owners ate their meals. It wasn’t hard—all he had to do was work a pulley that operated a system of paper fans—and he could be privy to the family’s conversations. They discussed news of the ongoing war between the South and the North, and the machinations of Abraham Lincoln, the man they deemed responsible for all their troubles.

In the slave quarters, however, Lincoln was a god. Booker T. was often awakened by the sound of his mother praying for Lincoln to win the war, so she and her children could be free. Other slaves shared her reverence for the Union leader and, according to Booker T., “all their dreams and hopes of freedom were in some way or other coupled with the name of Lincoln.”

In April 1865, Lincoln’s forces entered Richmond, Virginia, and Union soldiers brought news of victory to slaves throughout the state. Jane, her children, and the rest of the slaves were called to the big house. Assembled on the front porch, they listened excitedly as the Emancipation Proclamation was read to them by a Union officer. The incredible truth that they were free sank in.

As the Burroughses watched the rejoicing of their former slaves, they seemed sad, not only because of the loss of their property, Booker T. observed, but also because they would be “parting with those who were in many ways very close to them.”

Some slaves, especially the older ones, decided to stay with the Burroughses because they could not imagine a life other than the one they knew. But Jane made up her mind that the only way to experience freedom was to leave the plantation. The family jubilantly packed their belongings in a small cart and set out to join Wash Ferguson in West Virginia. Booker T. and his siblings had to walk and camp in the wilderness throughout the two-hundred-mile trek to their new home. There were long days, cold nights, and even a terrifying encounter with a giant snake in an abandoned cabin. But their newly acquired freedom made the band of travelers feel euphoric and invincible.

Casting a shadow over Booker T.’s happiness was the sad news of Abraham Lincoln’s assassination. The great leader was fatally shot on April 14, 1865. Even as Booker T. celebrated his own promising future, he mourned the death of his hero, who had virtually transformed him from a piece of property into a proud and independent citizen of the United States.

FIVE HUNDRED MILES from the backwoods of Virginia, in the heart of New York City, six-year-old Theodore Roosevelt and his little brother, Elliott, solemnly stood at a second-floor window in the Union Square mansion owned by their wealthy grandfather, Cornelius Van Schaack Roosevelt. It was April 25, 1865, and the two young boys were enthralled by the sight of Abraham Lincoln’s funeral procession passing directly in front of the house. The President’s body, which had been on view in Washington, DC, was on its way to its final resting place in Springfield, Illinois, by way of Baltimore, Harrisburg, Philadelphia, Jersey City, and New York, where a significant tribute was in progress.

Theodore, who was born in New York City on October 27, 1858, worshipped Lincoln. But one of his earliest life lessons was that there were two sides—a North and a South—to every story. His mother, Martha Bulloch, was a Southern belle who grew up on a plantation in Roswell, Georgia, while his father, Theodore Roosevelt Sr., was a philanthropic Northerner from one of New York’s original aristocratic Dutch families. “Mittie,” as Martha was called, and “Thee” adored each other and their four children: Anna (“Bamie”), Theodore (sometimes called “Teedie” in his youth, and later TR), Elliott, and Corinne.

The family enjoyed a genteel existence in their five-story brownstone at 28 East Twentieth Street. Mittie, who always dressed in white, was considered one of the most beautiful women in the city, and Thee was so involved in his children’s lives that they called him “Greatheart,” after the hero in John Bunyan’s allegory The Pilgrim’s Progress. Money was plentiful—Thee’s father owned a successful glass business—and his fortune enabled his sons to make fortunes of their own.

The Roosevelt children were a smart, energetic, and good-natured bunch. They were educated at home by their mother’s sister, Anna Bulloch, and fussed over by their grandmother Bulloch, who moved in with them after her husband died. Surrounded by doting relatives, they enjoyed a secure and privileged life, from the bountiful meals served in the family’s parlor floor dining room, to the toys and comfortable beds that awaited them in their upstairs nursery. The children had a few complaints—the horsehair furniture in the parlor was prickly, they suffered the occasional punishment for misbehavior, and TR’s recurring bouts of asthma sent the whole household into a panic, usually in the middle of the night. But, for the most part, the Roosevelts’ familial universe was a tranquil one until 1861, when the outbreak of the Civil War created understandable tension in a household torn by divided loyalties.

Mittie’s brothers, James and Irvine Bulloch, were conscientious Southern gentlemen who eagerly enlisted in the Confederate Army, and Mittie, her mother, and her sister shared their enthusiasm for the cause. Thee, on the other hand, was a staunch supporter of Lincoln and the Union Army. Knowing that his wife was terrified that he and her brothers might come face-to-face on the battlefield, Thee paid a thousand dollars to a surrogate to fight in his place, a common practice at the time. Not that he shirked his wartime responsibilities. The ever-diligent Roosevelt was the architect of the country’s first payroll savings program for soldiers, which enabled military men to put aside money for their families while they were off fighting the war.

TR honored his Southern roots when he helped his mother surreptitiously send care packages to her relatives in Georgia. And he paid homage to his father when he theatrically prayed aloud for the Union Army to “grind the Southern troops to powder,” something he did when he wanted to annoy his mother. Mittie and Thee maintained their relationship and their sense of humor, however, and managed to navigate these challenging wartime years.

The Roosevelts set aside their conflicting loyalties to pay tribute to Abraham Lincoln on the occasion of his funeral. The entire city was in mourning, its businesses closed and its silent buildings swathed in black, with crowds lining the streets, jockeying for the best vantage points. Lincoln’s hearse was drawn by sixteen gray horses and followed by a procession of fifty thousand mourners. The cortege was so big, and moved so slowly, that it took four hours to pass by the Roosevelts’ window. The boys had the best view in town when the procession stopped in Union Square for a memorial service. There were speeches, prayers, and a reading of poet William Cullen Bryant’s “Funeral Ode to Abraham Lincoln.” Despite the record number of spectators, the city was eerily silent. “New York showed its grief at Lincoln’s death amply and elegantly,” praised the New York Times.

There was one unfortunate backstage drama that almost spoiled the tribute. Inexplicably, the New York City planning committee refused to allow African Americans to march in the cortege, a shocking decision considering that Lincoln was responsible for freeing the slaves. If the dead man’s horse could follow him, why not “the men for whom President Lincoln fought and worked, and died,” incredulous members of the black community asked.

Ultimately, it took an irate telegram from the secretary of war to resolve the issue. “It is the desire of the Secretary of War that no discrimination respecting color should be exercised in admitting persons to the funeral procession in New York tomorrow,” snapped the official communiqué. Grieving blacks were permitted to join their white counterparts in the procession, where they could “drop a tear to the memory of their messiah and redeemer.” A journalist covering the story noted sarcastically, “That ended the war of the races.”

STRIVE AND SUCCEED

In the late 1860s, TR and Booker T. were young boys filled with energy, enthusiasm, and boundless curiosity: they embodied the new, postbellum spirit of America. The feeling was that anything could be accomplished with a little pluck and luck. This was the capitalist gospel preached by author Horatio Alger Jr. in his popular motivational novels, with such apt titles as Paddle Your Own Canoe; Sink, or Swim; and Strive and Succeed.

Ironically, Alger’s real-life story was not the lively and uplifting stuff of his fiction. As a young man, he aspired to be a writer and enjoyed some success with his short stories for juveniles. But his overbearing father, an old-school Unitarian minister, insisted his son follow in his footsteps. After dutifully graduating from divinity school in 1864, Alger accepted a position with a small congregation on Cape Cod. His career came to an abrupt end when two boys accused the young minister of sexual improprieties and the horrified church elders quickly sent him packing.

Alger moved to New York City, where he became fascinated with the lost boys—the homeless “newsies,” bootblacks, and street musicians who seemed to be everywhere after the Civil War. These vagabond children lived on the streets, supporting themselves as best they could. In 1854 they received a helping hand from the Children’s Aid Society, which opened the first Newsboys’ Lodging House, a refuge where a homeless boy could find a bed and a hot meal. One of the charity’s most active and enthusiastic patrons was Theodore Roosevelt Sr., who visited every Sunday and brought TR with him.

Alger was also a frequent visitor, and the boys he met at the Lodging House were the inspiration for “Ragged Dick,” “Paul the Peddler,” “Phil the Fiddler,” and dozens of other characters who became cultural icons for generations of admiring young readers. One of the writer’s biggest fans was seven-year-old TR, who enthusiastically read Alger’s short story “How Johnny Bought a Sewing-Machine” in his favorite children’s magazine, Our Young Folks.

TR recognized Johnny as a kindred spirit and embraced the idea that hard work, discipline, and courage could transform any boy into a hero, and any life into an adventure. The problem was that everyday survival was not an issue for the moneyed Roosevelts, so TR had to create his own adventures. Many of his ideas came from books. He was an enthusiastic reader who started working his way through the family library at such an early age that sometimes the oversized volumes were bigger than he was. TR was drawn to stories about great explorers, from Dr. Livingstone in the jungle to Natty Bumppo in the American West, to mythic heroes, such as Longfellow’s King Olaf, and to academic texts about science and natural history.

TR’s favorite roles were those of scientist and explorer, and he took them very seriously. He collected animals and insects for his “Roosevelt Museum of Natural History,” mimicking his father, who was one of the founders of the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. When writing about his bug collection, the young naturalist noted, “Now and then a friend has told me something about them but mostly I have gained their habbits from ofservation.” He even taught himself how to dissect and preserve specimens, and dramatically bemoaned the great “loss to science” when his mother threw away a stash of dead mice he had stored in the kitchen.

TR was bright, curious, daring, and wise beyond his years, but his quick mind and exuberant personality were trapped in a sickly body that held him back from the audacious life he imagined for himself. He was, in fact, the classic weakling who was always at the mercy of bullies. He was thin and gangly, and suffered from frequent debilitating bouts of asthma that left him gasping for breath and had his terrified parents administering coffee, cigars, bursts of cold air, and other desperate remedies meant to shock his lungs into working prop...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Description

- Praise

- About Deborah Davis

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: The Big House

- Chapter 2: Strive and Succeed

- Chapter 3: The Force that Wins

- Chapter 4: An Exemplary Young Gentleman

- Chapter 5: Brick by Brick

- Chapter 6: Great Expectations

- Chapter 7: Let Me Keep Loving

- Chapter 8: Moving Up

- Chapter 9: Rough Riding

- Chapter 10: Rising Stars

- Chapter 11: Jump Jim Crow

- Chapter 12: Pride and Prejudice

- Chapter 13: That Damned Cowboy

- Chapter 14: Best Behavior

- Chapter 15: Lazy Days

- Chapter 16: A Wild Ride

- Chapter 17: The People’s President

- Chapter 18: The Family Circus

- Chapter 19: Behind Closed Doors

- Chapter 20: Fathers and Daughters

- Chapter 21: Bold Moves

- Chapter 22: Dinner Is Served

- Chapter 23: A Big Stink

- Chapter 24: Sitting Ducks

- Chapter 25: Undercover

- Chapter 26: Blindsided

- Chapter 27: Slipping Away

- Eulogies

- Epilogue

- Photographs

- Acknowledgments

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index