The automotive assembly plant dominates its landscape, wherever in the world it’s located. From a distance, it is a vast windowless mass surrounded by acres of storage areas and railway yards. The complex shape of the building and the lack of a facade often make it hard to know just where to enter. Once inside, the scene is initially bewildering.

Thousands of workers in one vast building tend to streams of vehicles moving across the floor, while a complex network of conveyors and belts in the lofty ceiling carries parts to and fro. The scene is dense, hectic, noisy. On first exposure, it’s like finding oneself inside a Swiss watch—fascinating but incomprehensible and a little frightening, as well.

In 1986, at the outset of the IMVP, we set out to contrast lean production with mass production by carefully surveying as many of the world’s motor-vehicle assembly plants as possible. In the end, we visited and systematically gathered information on more than ninety plants in seventeen countries, or about half of the assembly capacity of the entire world. Ours would prove one of the most comprehensive international surveys ever undertaken in the automobile or any other industry.

This chapter is based on the IMVP World Assembly Plant Survey. The survey was initiated by John Krafcik, who was later joined by John Paul MacDuffie. Haruo Shimada also assisted.

Why did we choose the assembly plant for study? Why not the engine plant, say, or the brake plant or the alternator factory? And why so many plants in so many countries? Surely, the best lean-production plant in Japan and the worst mass-production plant in North America or Europe would have sufficiently demonstrated the differences between lean and mass production.

Three factors convinced us that the assembly plant was the most useful activity in the motor-vehicle production system to study.

First, a large part of the work in the auto industry involves assembly. This is so simply because of the large number of parts in a car. Much of this assembly occurs in components plants. For example, an alternator plant will gather from suppliers or fabricate the 100 or so discrete parts in an alternator, then assemble them into a complete unit. However, it’s hard to understand assembly in such a plant, because the final activity usually makes up only a small part of the total. In the final assembly plant, by contrast, the sole activity is assembly—welding and screwing several thousand simple parts and complex components into a finished vehicle.

Second, assembly plants all over the world do almost exactly the same things, because practically all of today’s cars and light trucks are built with very similar fabrication techniques. In almost every assembly plant, about 300 stamped steel panels are spot-welded into a complete body. Then the body is dipped and sprayed to protect it from corrosion. Next, it is painted. Finally, thousands of mechanical parts, electrical items, and bits of upholstery are installed inside the painted body to produce the complete automobile. Because these tasks are so uniform, we can meaningfully compare a plant in Japan with one in Canada, another in West Germany, and still another in China, even though they are making cars that look very different as they emerge from the factory.

Finally, we chose the assembly plant for study, because Japanese efforts to spread lean production by building plants in North America and Europe initially involved assembly plants. When we began our survey in 1986, three Japanese-managed assembly plants were already in operation in the United States and one was ready to open in England.

By contrast, Japanese plants for engines, brakes, alternators, and other components, though publicly announced for North America and Europe, were still in the planning stage. We knew from experience that it’s pointless to examine a company’s blueprints for a new plant or to look at a plant just as it starts production. To see the full difference between lean and mass production at the plant level, we had to compare plants operating at full volume.

What about the second question we are often asked: “Why study so many plants in so many countries?” The answer is simple. Lean production is now spreading from Japan to practically every nation. Directly in its path are the giant mass-production plants of the previous industrial era.

In every country and every company—including, we might add, in the less accomplished companies in Japan—we have found an intense, even desperate, desire to know the answer to two simple questions: “Where do we stand?” and “What must we do to match the new competitive level required by lean production?” Now we know the answers.

CLASSIC MASS PRODUCTION: GM FRAMINGHAM

We began our survey in 1986 at General Motors’ Framingham, Massachusetts, assembly plant, just a few miles south of our home base in Boston. We chose Framingham, not because it was nearby, but because we strongly suspected it embodied all the elements of classic mass production.

Our first interview with the plant’s senior managers was not promising. They had just returned from a tour of the Toyota-GM joint-venture plant (NUMMI) where John Krafcik, our assembly-plant survey leader, formerly worked. One reported that secret repair areas and secret inventories had to exist behind the NUMMI plant, because he hadn’t seen enough of either for a “real” plant. Another manager wondered what all the fuss was about. “They build cars just like we do.” A third warned that “all that NUMMI talk [about lean production] is not welcome around here.”

Despite this cold beginning, we found the plant management enormously helpful. All over the world, as we have since discovered again and again, managers and workers badly want to learn where they stand and how to improve. Their fear of just how bad things might be is in fact what often creates initial hostility.

On the plant floor, we found about what we had expected: a classic mass-production environment with its many dysfunctions. We began by looking down the aisles next to the assembly line. They were crammed with what we term indirect workers—workers on their way to relieve a fellow employee, machine repairers en route to troubleshoot a problem, housekeepers, inventory runners. None of these workers actually add value, and companies can find other ways to get their jobs done.

Next, we looked at the line itself. Next to each work station were piles—in some cases weeks’ worth—of inventory. Littered about were discarded boxes and other temporary wrapping material. On the line itself the work was unevenly distributed, with some workers running madly to keep up and others finding time to smoke or even read a newspaper. In addition, at a number of points the workers seemed to be struggling to attach poorly fitting parts to the Oldsmobile Ciera models they were building. The parts that wouldn’t fit at all were unceremoniously chucked in trash cans.

At the end of the line we found what is perhaps the best evidence of old-fashioned mass production: an enormous work area full of finished cars riddled with defects. All these cars needed further repair before shipment, a task that can prove enormously time-consuming and often fails to fix fully the problems now buried under layers of parts and upholstery.

On our way back through the plant to discuss our findings with the senior managers, we found two final signs of mass production: large buffers of finished bodies awaiting their trip through the paint booth and from the paint booth to the final assembly line, and massive stores of parts, many still in the railway cars in which they had been shipped from General Motors’ components plants in the Detroit area.

Finally, a word on the workforce. Dispirited is the only label that would fit. Framingham workers had been laid off a half-dozen times since the beginning of the American industry’s crisis in 1979, and they seemed to have little hope that the plant could long hold out against the lean-production facilities locating in the American Midwest.

CLASSIC LEAN PRODUCTION: TOYOTA TAKAOKA

Our next stop was the Toyota assembly plant at Takaoka in Toyota City. Like Framingham (built in 1948), this is a middle-aged facility (from 1966). It had a much larger number of welding and painting robots in 1986 but was hardly a high-tech facility of the sort General Motors was then building for its new GM-10 models, in which computer-guided carriers replaced the final assembly line.

The differences between Takaoka and Framingham are striking to anyone who understands the logic of lean production. For a start, hardly anyone was in the aisles. The armies of indirect workers so visible at GM were missing, and practically every worker in sight was actually adding value to the car. This fact was even more apparent because Takaoka’s aisles are so narrow.

Toyota’s philosophy about the amount of plant space needed for a given production volume is just the opposite of GM’s at Framingham: Toyota believes in having as little space as possible so that face-to-face communication among workers is easier, and there is no room to store inventories. GM, by contrast, has believed that extra space is necessary to work on vehicles needing repairs and to store the large inventories needed to ensure smooth production.

The final assembly line revealed further differences. Less than an hour’s worth of inventory was next to each worker at Takaoka. The parts went on more smoothly and the work tasks were better balanced, so that every worker worked at about the same pace. When a worker found a defective part, he—there are no women working in Toyota plants in Japan—carefully tagged it and sent it to the quality-control area in order to obtain a replacement part. Once in quality control, employees subjected the part to what Toyota calls “the five why’s” in which, as we explained in Chapter 2, the reason for the defect is traced back to its ultimate cause so that it will not recur.

As we noted, each worker along the line can pull a cord just above the work station to stop the line if any problem is found; at GM only senior managers can stop the line for any reason other than safety—but it stops frequently due to problems with machinery or materials delivery. At Takaoka, every worker can stop the line but the line is almost never stopped, because problems are solved in advance and the same problem never occurs twice. Clearly, paying relentless attention to preventing defects has removed most of the reasons for the line to stop.

At the end of the line, the difference between lean and mass production was even more striking. At Takaoka, we observed almost no rework area at all. Almost every car was driven directly from the line to the boat or the trucks taking cars to the buyer.

On the way back through the plant, we observed yet other differences between this plant and Framingham. There were practically no buffers between the welding shop and paint booth and between paint and final assembly. And there were no parts warehouses at all. Instead parts were delivered directly to the line at hourly intervals from the supplier plants where they had just been made. (Indeed, our initial plant survey form asked how many days of inventory were in the plant. A Toyota manager politely asked whether there was an error in translation. Surely we meant minutes of inventory.)

A final and striking difference with Framingham was the morale of the workforce. The work pace was clearly harder at Takaoka, and yet there was a sense of purposefulness, not simply of workers going through the motions with their minds elsewhere under the watchful eye of the foreman. No doubt this was in considerable part due to the fact that all of the Takaoka workers were lifetime employees of Toyota, with fully secure jobs in return for a full commitment to their work.1

A BOX SCORE: MASS PRODUCTION VERSUS LEAN

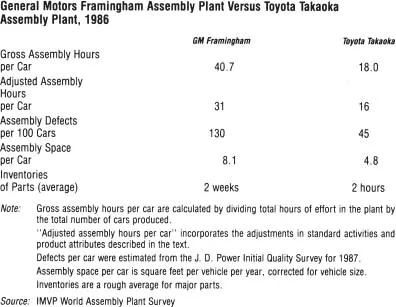

When the team had surveyed both plants, we began to construct a simple box score to tell us how productive and accurate each plant was (“accurate” here means the number of assembly defects in cars as subsequently reported by buyers).2 It was easy to calculate a gross productivity comparison, dividing the number of hours worked by all plant employees by the number of vehicles produced, as shown in the top line of Figure 4.13 However, we had to make sure that each plant was performing exactly the same tasks. Otherwise, we wouldn’t be comparing apples with apples.

So we devised a list of standard activities for both plants—welding of all body panels, application of three coats of paint, installation of all parts, final inspection, and rework—and noted any task one plant was doing that the other wasn’t. For example, Framingham did only half its own welding and obtained many prewelded assemblies from outside contractors. We made an adjustment to reflect this fact.

We also knew it would make little sense to compare plants assembling vehicles of grossly different sizes and with differing amounts of optional equipment, so we adjusted the amount of effort in each plant as if a standard vehicle of a specified size and option content were being assembled.4

FIGURE 4.1

When our task was completed, an extraordinary finding emerged, as shown in Figure 4.1. Takaoka was almost twice as productive and three times as accurate as Framingham in performing the same set of standard activities on our standard car. In terms of manufacturing space, it was 40 percent more efficient, and its inventories were a tiny fraction of those at Framingham.

If you remember Figure 2.1 from Chapter 2, you might wonder whether this leap in performance from classic mass production, as practiced by GM, to classic lean production, as performed by Toyota, really deserves the term revolution. After all, Ford managed to reduce direct assembly effort by a factor of nine at Highland Park.

In fact, Takaoka is in some ways an even more impressive achievement than Ford’s at Highland Park, because it represents an advance on so many dimensions. Not only is effort cut in half and defects reduced by a factor of three, Takaoka also slashes inventories and manufacturing space. (That is, it is both capital-and labor-saving compared with Framingham-style mass production.) What’s more, Takaoka is able to change over in a few days from one type of vehicle to the next generation of product, while Highland Park, with its vast array of dedicated tools, was closed for months in 1927 when Ford switched from the Model T to the new Model A. Mass-production plants continue to close for months while switching to new products.

DIFFUSING LEAN PRODUCTION

Revolutions in manufacture are useful only if they are available to everyone. We were therefore vitally interested in learning if the new transplant facilities being opened in North America and Europe could actually institute lean production in a different environment.

We knew one of the Japanese transplants in North America very well, of course, because of IMVP research affiliate John Krafcik’s tenure there. The New United Motor Manufacturing Inc. (NUMMI) plant in Fremont, California, is a joint venture between the classic mass producer, GM, and the classic lean producer, Toyota.

NUMMI uses an old General Motors plant built in the 1960s to assemble GM cars and pickup trucks for the U.S. West Coast. As GM’s market share along the Pacific Coast...