- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

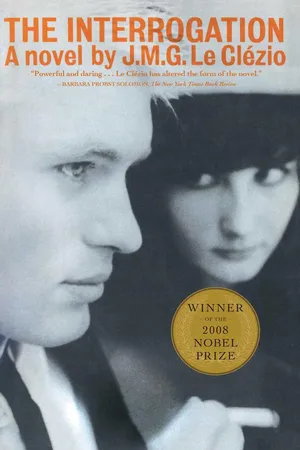

From the original Atheneum edition jacket, 1964.

"J.M.G. Le Clézio, revelation of the literary year" ran the headline of the Paris Express after last year's prizes had been awarded. The Goncourt jury was locked five to five until its president used his double vote to give the prize to the older candidate. Ten minutes later the Renaudot jury elected the candidate they thought they might lose to the other prize. Most of the literary sections ran their prize news putting the Renaudot first, in order to feature the twenty-three-year-old discovery that was rocking Paris literary circles.

What is The Interrogation? Most likely a myth without distinct delineations. A very solitary young man, Adam Pollo, perhaps the first man, perhaps the last, has a very remarkable interior adventure. He concentrates and he discovers ways of being, ways of seeing. He enters into animals, into a tree.... He has no business, no distractions; he is at the complete disposal of life. All of life, that is, except the society of his own species -- and so the story ends.

"This is the next phase after the 'the new novel,'" wrote the critics. Kafka they said; a direct descendant of Joyce, they said. Beckett they said. Like nothing else, they said. One hundred thousand Frenchmen bought it. They said it was strange and beautiful. Finally the real voice of the young, said the critics. "I like J. D. Salinger," said Mr. Le Clézio, and that was all he said. His remarkable first book will soon be published all over the world and much more will be said.

"J.M.G. Le Clézio, revelation of the literary year" ran the headline of the Paris Express after last year's prizes had been awarded. The Goncourt jury was locked five to five until its president used his double vote to give the prize to the older candidate. Ten minutes later the Renaudot jury elected the candidate they thought they might lose to the other prize. Most of the literary sections ran their prize news putting the Renaudot first, in order to feature the twenty-three-year-old discovery that was rocking Paris literary circles.

What is The Interrogation? Most likely a myth without distinct delineations. A very solitary young man, Adam Pollo, perhaps the first man, perhaps the last, has a very remarkable interior adventure. He concentrates and he discovers ways of being, ways of seeing. He enters into animals, into a tree.... He has no business, no distractions; he is at the complete disposal of life. All of life, that is, except the society of his own species -- and so the story ends.

"This is the next phase after the 'the new novel,'" wrote the critics. Kafka they said; a direct descendant of Joyce, they said. Beckett they said. Like nothing else, they said. One hundred thousand Frenchmen bought it. They said it was strange and beautiful. Finally the real voice of the young, said the critics. "I like J. D. Salinger," said Mr. Le Clézio, and that was all he said. His remarkable first book will soon be published all over the world and much more will be said.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

A. Once upon a little time, in the dog-days, there was a fellow sitting at an open window; he was an inordinately tall boy with a slight stoop, and his name was Adam; Adam Pollo. He had the air of a beggar in his way of looking everywhere for patches of sunshine and sitting for hours practically motionless in the angle of a wall. He never knew what to do with his arms, he usually left them to dangle at his sides, touching his body as little as possible. He was like one of those sick animals that make a canny retreat into some refuge and watch stealthily for danger, the kind that comes creeping along the ground and hides in its skin, blending right into it. Now he was lying on a deck-chair by the open window, naked to the waist, bare-headed, bare-footed, with the sky slanting overhead. All he had on was a pair of beige linen trousers, shabby and sweat-stained; he had rolled the legs up to his knees.

The yellow sunshine was hitting him full in the face, but without glancing off again: it was immediately absorbed by his damp skin, striking no sparks, not even the faintest little gleam. He guessed as much and made no movement, except that from time to time he lifted a cigarette to his lips and drew in a gulp of smoke.

When the cigarette was finished, when it burnt his thumb and fore-finger and he had to drop it on the floor, he took a handkerchief from his trousers pocket and with great deliberation wiped his chest and forearms, the base of his throat and his armpits. Once rid of the thin film of sweat which had protected it until that moment, his skin began to glow like fire, red with light. Adam got up and walked quickly to the back of the room, into the shade; from the pile of blankets on the floor he pulled out an old shirt made of cotton, flannelette or calico, shook it and slipped it on. When he bent down, the tear in the middle of the back, between his shoulder-blades, opened in a way it had, to the size of a coin, and revealed, at random, three pointed vertebrae which stuck out beneath the taut skin like fingernails under thin rubber.

Without even buttoning his shirt, Adam took from among the blankets a kind of yellow exercise-book, the sort used in schools, in which the first page was headed, like the beginning of a letter:

My dear Michèle, then he went back to sit in front of the window, protected now from the rays of the sun by the material that clung to his ribs. He opened the exercise-book on his knees, ruffled briefly through the pages covered with closely-written sentences, produced a ball-point pen from his pocket, and read:

‘My dear Michèle,

I would so much like this house to stay empty. I hope the owners won’t come back for a long time.

This is how I’d dreamt of living for ages: I put up two deck-chairs facing each other, just under the window; like that, about midday, I lie down and sleep in the sun, turned towards the view, which is beautiful, so they say. Or else I turn away a little towards the light, throwing my head into full relief. At four o’clock I stretch out further, provided the sun is lower or shining in more directly; by that time it’s about ¾ down the window. I look at the sun, perfectly round; at the sea, that’s to say the horizon, right up against the window-rail, perfectly straight. I spend every minute at the window, and I pretend all this is mine, silently, and no one else’s. It’s funny. I’m like that the whole time, in the sun, almost naked, and sometimes quite naked, looking carefully at the sky and the sea. I’m glad people think everywhere that I’m dead; at first I didn’t know this was a deserted house; that kind of luck doesn’t come often.

When I decided to live here I took all I needed, as though I were going fishing, I came back in the night, and then I toppled my motorbike into the sea. Like that I gave the impression I was dead, and I didn’t need to go on making everyone believe I was alive and had heaps of things to do, to keep myself alive.

The funny thing is that no one took any notice, even at the beginning; luckily I hadn’t too many friends, and I didn’t know any girls, because they’re always the first to come and tell you to stop playing the fool, to get back to the town and begin all over again as though nothing had happened: that’s to say cafés, cinemas, railways, etc.

From time to time I go into town to buy stuff to eat, because I eat a lot, and often. Nobody asks me questions, and I don’t have to talk too much; that doesn’t worry me, because years ago they got me into the habit of keeping my mouth shut, and I could easily pass for deaf, dumb and blind.’

He paused for a few seconds and wiggled his fingers as though to relax them; then he bent over the exercise-book again, so that the little veins in his temples swelled and the egg-shaped, hirsute lump of his skull was exposed to the savage thrusts of the sun. This time he wrote: ‘My dear Michèle,

Thanks to you, Michèle—for you exist, I believe you—I have my only possible contact with the world down the hill. You go to work, you’re often in the town, at the different street crossings, among the blinking lights and God knows what. You tell heaps of people you know a chap who lives alone in a deserted house, a complete nut; and they ask you why he isn’t shut up in a loony-bin. I assure you I’ve nothing against it, I’ve no cervical complex and I think that’s as good a way as any other to end one’s days—in peace, in a comfortable house, with a formal French garden and people to see that you get your meals. The rest doesn’t matter, and there’s nothing to prevent one from being full of imagination and writing poems—this kind of thing:

today, day of the rats,

last day before the sea.

last day before the sea.

Fortunately I can make you out amidst a mass of memories, like when we used to play hide-and-seek and I would catch sight of your eye, your hand or you hair between clusters of round leaves, and thinking about it all of a sudden I would discard my faith in appearances and cry shrilly: “Seen you!”.’

He thought about Michèle, about all the children she’d be having sooner or later, in any case; irrationally, that didn’t matter, he could wait. He would tell those children a whole heap of things, when the time came. He’d tell them, for instance, that the earth was not round, that it was the centre of the universe, and that they were the centre of everything, without exception. Then they would no longer be in danger of losing themselves, and (unless they got polio, of course) they would have 99 chances in a hundred of going about like those children he had seen last time he went to the beach—shouting, yelling, chasing rubber balls.

He would tell them, too, that there was only one thing to be afraid of—that the earth might turn over, so that they would be head downwards with their feet in the air, and that the sun might fall down on the beach, about six o’clock, making the sea boil so that all the little fishes would burst.

Dressed now, he sat in the deck-chair and looked out of the window; to do this he had to raise the cross-bar of the chair to the highest notch. The hill went down to the road in a slope that was half gradual and half steep, jumped four or five yards; and then came the water. Adam couldn’t get a complete view; there were lots of pines and other trees and telegraph poles in the way, so he had to imagine parts of it. Sometimes he wasn’t sure whether he’d guessed right, so he had to go all the way down. As he walked along he could see the skein of lines and curves unravelling, different things would splinter off and gleam; but the fog gathered again further ahead. One could never be definite about anything in this kind of landscape; one was always more or less a queer unknown quantity, but in an unpleasant way. Call it something like a squint or a slight exophthalmic goitre; the house itself, or the sky, or it might be the curve of the bay, would become obscured from view as Adam walked down. For shrubs and brushwood wove an uninterrupted screen in front of them; at ground-level the air quivered in the heat, and the far horizon seemed to be rising in puffs of light smoke from among the blades of grass.

The sun distorted certain things, too. Beneath its rays the road would liquify in whitish patches; sometimes when a line of cars was going by, the black metal would burst like a bomb for no apparent reason, a spiral of lightning would flash from the bonnet and make the entire hill blaze and bend, shifting the atmosphere by a few millimetres with a thrust of its halo.

That was at the beginning, really at the beginning; for afterwards he began to understand what it meant, monstrous solitude. He opened a yellow exercise-book and wrote at the top of the first page, as though beginning a letter:

‘My dear Michèle,’

He used to play music as well, like everyone else; once, in the town, he had stolen a plastic pipe from a toy-stall. He had always wanted a pipe and he’d been delighted to have this one. It was a toy pipe, of course, but good quality, it came from the U.S. So when he felt inclined he would sit in the deck-chair at the open window and play gentle little tunes. Rather afraid of attracting people’s attention, because there were days when fellows and girls used to come and lie down in the grass, round the house. He played softly, with infinite gentleness, making almost inaudible sounds, blowing hardly at all, pressing the tip of his tongue against the mouthpiece and pulling in his diaphragm. Now and then he would break off and rattle his fingertips along a row of empty tins, arranged in order of size; that made a soft rustling, rather like bongo drums, which went zigzagging away in the air, rather like the howls of a dog.

And that was the life of Adam Pollo. At night he would light the candles at the back of the room and take up his position at the open window in the faint sea-breeze, standing absolutely erect, full of the energy that the dusty noonday takes from a man.

He would wait a long time, without moving, proud of being almost dehumanized, until the first flights of moths arrived, tumbling, hesitating outside the empty hole of the window, pausing in concentration and then, maddened by the yellow blink of the candles, launching a sudden attack. Then he would lie down on the floor, among the blankets, and stare fixedly at the hustling swarm of insects, more and more of them, thronging the ceiling with a multiplicity of shadows and collapsing into the flames, making a wreath of tiny legs round the corolla of boiling wax, sizzling, scraping the air like files against a granite wall, and smothering, one by one, every glimmer of light.

For someone in Adam’s circumstances, and who had been trained to meditation by years at a university and a life devoted to reading, there was nothing to do except think of things like this and avoid madness; hence it was probable that only fear (of the sun, to take one example) could help him to remain within the bounds of moderation and, should the occasion arise, to go back to the beach. With this in mind, Adam had now slightly changed his usual position: leaning forward, he had turned his face towards the back of the room and was looking at the wall. Seeing the light dimly across his left shoulder, he was forcing himself to imagine that the sun was an immense golden spider, its rays covering the sky like tentacles, some twisting, others forming a huge W, clinging to projections in the ground, to every escarpment, at fixed points.

All the other tentacles were undulating slowly, lazily, dividing into branches, separating into countless ramifications, splitting open and immediately closing up again, waving to and fro like seaweed.

To make sure, he had drawn it in charcoal on the wall opposite.

So now he was sitting with his back to the window, and could feel terror creeping over him as the minutes went by and he contemplated the tangle of claws, the savage medley that he could no longer understand. Apart from its special aspect of something dry and charred which was shining and sprinkling, it was a kind of horrible, deadly octopus, with its hundred thousand slimy arms like horses’ guts. To give himself courage he talked to the drawing, looking at its exact centre, at the anthracite ball from which the tentacles flowed out like roots calcinated in some past age; he addressed it in rather childish words:

‘you’re a beauty—beautiful beast, beautiful beast, there,

you’re a nice sun, you know, a beautiful black sun.’ He knew he was on the right track.

And sure enough, he gradually managed to reconstruct a world of childish terrors; seen through the rectangle of the window, the sky seemed ready to break away and crash down on our heads. The sun, ditto. He looked at the ground and saw it suddenly melting, boiling, or flowing beneath his feet. The trees grew excited and gave off poisonous vapours. The sea began to swell, devoured the narrow grey strip of beach and then rose, rose to attack the hill, to drown him, moving towards him, to numb him, to swallow him up in its dirty waves. He could feel the fossilized monsters coming to birth somewhere, prowling round the villa, the joints of their huge feet cracking. His fear grew, invincible, imagination and frenzy could not be checked; even human beings become hostile, barbarous, their limbs sprouted wool, their heads shrank, and they advanced in serried ranks over the countryside, cannibalistic, cowardly or ferocious. The moths flung themselves on him, biting him with their mandibles, wrapping him in the silky veil of their hairy wings. From the pools there rose an armoured nation of parasites or shrimps, of abrupt, mysterious crustaceans, hungering to tear off shreds of his flesh. The beaches were covered with strange creatures who had come there, accompanied by their young, to await no one knew what; animals prowled along the roads, growling and squealing, curious parti-coloured animals whose shells glistened in the sunshine. Everything was suddenly in motion, with an intense, intestinal, concentrated life, heavy and incongruous as a kind of submarine vegetation. While this was going on he drew back into his corner, ready to spring out and defend himself pending the final assault that would leave him the prey of these creatures. He picked up the yellow exercise-book of a little while back, looked again for a moment at the drawing on the wall, the drawing which had once represented the sun; and he wrote to Michèle:

‘My dear Michèle,

I must admit I’m a little frightened, here in the house. I think if you were here, in the light, lying naked on the ground, and I could recognize my own flesh in yours, smooth and warm, I shouldn’t need all that. While I’m writing you this, just imagine, there happens to be a narrow space, between the deck-chair and the skirting-board, that would fit you like a glove; it’s exactly your length, 5 ft. 4, and I don’t think its hip measurement is more than yours, 35½. So far as I’m concerned the earth has turned into a sort of chaos, I’m scared of the deinotheria, the pithecanthropes, the Neanderthal man (a cannibal), not to mention the dinosaurs, the labyrinthosaurs, the pterodactyls, etc. I’m afraid the hill may turn into a volcano.

Or that the polar ice may melt, which would raise the level of the sea and drown me. I’m afraid of the people on the beach, BELOW. The sand is changing into quicksands, the sun into a spider and the children into shrimps.’

Adam closed the exercise-book with a snap, raised himself on his forearms, and looked out of the window. There was nobody coming. He reckoned how much time he would need to go down to the sea, bathe and get back. It was too late in the day; he had rather forgotten how long it was since he’d last been out of the house—two days, or more.

It looked as though he had been living entirely on biscuits —cut-price wafers bought at the Prisunic. Now and then he felt a pain in his stomach, and there was a sour taste round his glottis. He leant out of the window and contemplated the small section of the town that could be seen on the right, between two hills.

He lit a cigarette, one of the few remaining from the collection of eight assorted packets bought when he last went out, and said aloud:

‘What’s the use of going into town? It’s not worth while working like I do at these crazy things—getting scared stiff, in fact—believing that if I don’t go there, it’s they who’ll come here and kill me, yes, yes. I understand, my psychological reflexes have gone … but before that? Before that I could do one thing or another, and nowadays heaps of things convince me that it’s finished. Adam, for God’s sake, it’s an effort for me to go down among all those buildings, to hear people shouting, grumbling, arguing, etc., listening to them all by myself in a corner of the wall. Sooner or later one has to bring out a word or two, say yes, thank you, excuse me, it’s a beautiful evening but of course it’s true that yesterday was, I’m fresh from college, and it’s only fair, it would be only fair for all that muck to come to an end, and all that useless, idiotic, bloody chatter which is the reason why I’m here this evening, needing fresh air and cigarettes and with malnutrition lying in wait, asking myself why there shouldn’t be just a very few more unimaginable things.’

He took a step backwards, blew smoke through his nostrils, and went on, still talking to himself (but luckily he didn’t overdo that, no—partly because he had never been talkative).

‘Splendid, splendid—that’s all very fine, but I must go into town to buy fags, beer, chocolate and stuff to eat.”

To make it clearer he wrote on a scrap of paper:

fags

beer

chocolate

stuff to eat

paper

newspapers if

possible take

a look round

beer

chocolate

stuff to eat

paper

newspapers if

possible take

a look round

Then he sat down on the floor, by the window, in the sun, where he usually waits for dark, and to rest himself he began drawing signs in the dust, aimless patterns of fine lines, scratched with a fingernail. Because of course it’s tiring to live all alone like that, in a deserted house at the top of a hill. It means knowing how to look after yourself, enjoying fear, idleness and the unusual, wanting to dig lairs all the time and to hide in them, abasing yourself, keeping well concealed as you used to do when you were a kid, between two ragged pieces of old tarpaulin.

B. He had fetched up on the beach. He was lying on the pebbles at the extreme left, close to the piled-up rocks and the fringe of seaweed, an ideal place for flies to lay their eggs. He had just been swimming and now he was leaning back, propped on his elbows, leaving a small space, conducive to evaporation, between his wet back and the ground. His skin was dark red, not brown, and it clashed with his swimming-trunks, which were painted bright blue. From a distance he looked like an American tourist, but coming nearer one noticed that his face was dirty, his hair too long, and his straggling beard had been hacked off with scissors. His head hung listlessly on his chest.

His elbows were resting side by side on a bath-towel, but from the shoulder-blades downwards his body was in direct contact with the beach, and muddy patches of gravel had stuck to the hairs on his legs. With his head turned this way he could presumably see very little of the water, it would be chiefly the boulders to the left that met his eye; and assuming that these had not been washed for centuries, that for centuries men and animals had been covering them with filth, one could understand his air of vague disgust. Naturally the beach was crowded from end to end (Adam was at the extreme south-east) with people, mostly women and children, walking, sleeping or shouting, all in their different ways.

Adam had dozed for a time, like that, or even dropped right off; in the end he’d thought it would be better to stroll on and find a spot of shade somewhere. He had given himself until two o’clock,...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Interrogation by J. M. G. Le Clezio in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literature General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.