- 526 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

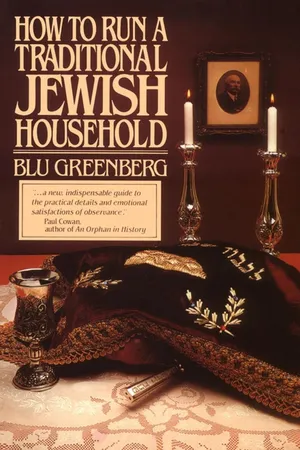

How to Run a Traditional Jewish Household

About this book

Told with warmth and understanding, this modern guide explores virtually every aspect of Jewish home life, showing that—contrary to popular belief—the home, and not the synagogue, is the most important institution in Jewish life.

In How to Run a Traditional Jewish Household, Blu Greenberg opens the door to the heart of Jewish living, offering both practical wisdom and rich historical insight. With warmth, clarity, and authenticity, she explores what it means to create a home grounded in Jewish law, spirit, and culture.

Divided into three illuminating sections—The Jewish Way, Special Stages of Life, and Celebration and Remembering—this essential book covers every aspect of daily Jewish life: prayer, dress, holidays, food preparation, marriage, parenthood, and the sacred milestones that shape a family’s journey.

For those rediscovering their heritage, Greenberg offers an approachable, flexible guide—one that teaches the why behind each tradition as much as the how. For the observant, she provides thoughtful insights and expert detail to deepen existing practice. With a voice that is both deeply traditional and refreshingly modern, Greenberg also speaks to women navigating the intersection of faith and feminism.

Greenberg’s understanding, empathy, and expertise make this book not just a manual—but a conversation, an inspiration, and a celebration of Jewish life. How to Run a Traditional Jewish Household is a timeless guide for anyone seeking to live—and love—the rhythms of Jewish tradition in the modern world.

In How to Run a Traditional Jewish Household, Blu Greenberg opens the door to the heart of Jewish living, offering both practical wisdom and rich historical insight. With warmth, clarity, and authenticity, she explores what it means to create a home grounded in Jewish law, spirit, and culture.

Divided into three illuminating sections—The Jewish Way, Special Stages of Life, and Celebration and Remembering—this essential book covers every aspect of daily Jewish life: prayer, dress, holidays, food preparation, marriage, parenthood, and the sacred milestones that shape a family’s journey.

For those rediscovering their heritage, Greenberg offers an approachable, flexible guide—one that teaches the why behind each tradition as much as the how. For the observant, she provides thoughtful insights and expert detail to deepen existing practice. With a voice that is both deeply traditional and refreshingly modern, Greenberg also speaks to women navigating the intersection of faith and feminism.

Greenberg’s understanding, empathy, and expertise make this book not just a manual—but a conversation, an inspiration, and a celebration of Jewish life. How to Run a Traditional Jewish Household is a timeless guide for anyone seeking to live—and love—the rhythms of Jewish tradition in the modern world.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access How to Run a Traditional Jewish Household by Blu Greenberg in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Jewish Theology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

The Jewish Way

One of the most remarkable qualities of the Jewish religion is its ability to sanctify everyday life—the routine, the mundane, the necessary bits and pieces of daily existence. This is achieved through the guidelines of halacha, the body of Jewish law and ethics that defines the Jewish way through life. What Judaism says in effect is this: Yes, commemorating a unique event in history is a holy experience, but so is the experience of waking up alive each morning, or eating to nourish the body, or having sex with one’s mate; so is the act of establishing clear demarcations between work and rest or investing everyday speech and dress with a measure of sanctity. Judaism takes the physical realities of life and imposes on them a set of rules or rituals. By doing so, it transforms this reality or that basic necessity of life into something beyond itself. That is the heart of the Jewish Way.

CHAPTER · 1

SHABBAT*

THE SEVENTH DAY

Time. Jews have an amazing way with time. We create islands of time. Rope it off. Isolate it. Put it on another plane. In doing so, we create within that time a special aura around our everyday existence. Carving out special segments of holy time suits the human psyche perfectly, for ordinary human beings cannot live constantly at the peak of emotion. Thus, Shabbat, holy time, gives us an opportunity to experience that emotional peak, to feel something extraordinary in an otherwise ordinary span of time.

You would not think of time as having texture, yet in a traditional Jewish household it becomes almost palpable. On Shabbat, I can almost feel the difference in the air I breathe, in the way the incandescent lamps give off light in my living room, in the way the children’s skins glow, or the way the trees sway. Immediately after I light my candles, it is as if I flicked a switch that turned Shabbat on in the world, even though I know very well the world is not turned on to Shabbat. Remarkable as this experience is, even more remarkable is that it happens every seventh day of my life.

How does it happen? There will always be an element of mystery in transforming time from ordinary to extraordinary, but the human part of the process is not mysterious at all. It is not one great big leap or one awesome encounter with the Holy, but rather just so many small steps, like parts of a pattern pieced together.

Why do I or any other Orthodox Jew take these steps, week after week, month after month, year after year, with never a slipup? The first answer falls hard on untrained ears. I observe Shabbat the way I do because I am so commanded. Somewhere in that breathtaking desert, east of Egypt and south of Israel, Moses and the Jewish people received the Torah, including the commandment to observe Shabbat. Since I am a descendant of those people, my soul, too, was present at Sinai, encountered God, and accepted the commandments.

Now, I don’t for a moment believe that God said at Sinai, “Do not carry money in your pockets on Shabbat,” or, “Do not mow thy front lawn,” or even, “Go to synagogue to pray,” but the cumulative experience of Revelation, plus the way that experience was defined and redefined in History for a hundred generations of my ancestors, carries great weight with me.

The Biblical commandment to observe Shabbat has two reference points: God’s creation of the world, and the Exodus/freedom from slavery. True, these are events in history, yet, linked as they both are to Shabbat, they also suggest something else about the human condition: that there is a tension between the poles of one’s life, mastery at the one end and enslavement at the other; mastery in drive, energy, creativity—and enslavement to the pressures and seduction of the hurly-burly world.

To some extent, Shabbat achieves what the song title suggests: “Stop the World, I Want to Get Off.” Let me paraphrase the Biblical injunction, as it speaks to me, a contemporary person:

Six days shall you be a workaholic; on the seventh day, shall you join the serene company of human beings.

Six days shall you take orders from your boss; on the seventh day, shall you be master/mistress of your own life.

Six days shall you toil in the market; on the seventh day, shall you detach from money matters.

Six days shall you create, drive, create, invent, push, drive; on the seventh day, shall you reflect.

Six days shall you be the perfect success; on the seventh day, shall you remember that not everything is in your power.

Six days shall you be a miserable failure; on the seventh day, shall you be on top of the world.

Six days shall you enjoy the blessings of work; on the seventh day, shall you understand that being is as important as doing.

A friend has this bumper sticker affixed to the front of her refrigerator: HANG IN THERE, SHABBOS IS COMING. There definitely are weeks in my life when I feel that I will barely make it, but the prize of Shabbat carries me through.

It doesn’t always work this way. There are times on Friday night that my best ideas come to me. I feel the urge to take pen in hand and write my magnum opus, but I am not allowed to write. There are those weeks when I am just not in the mood for a big Friday-night family dinner. There have been some Shabbat mornings when it might have been more fun on the tennis court than in shul, and there were some Saturday afternoons when I had to miss what I was sure was the world’s best auction.

Happily, the negative moods are the exception and the positive ones the rule. (Were it otherwise, commanded or not, I might have walked away as most modern Jews have done—without, I am well aware, being struck down.) But more important is the fact that I never have to think about picking and choosing. I am committed to traditional Judaism. It has chosen me and I have chosen it back. And just as I am commanded to observe the laws on a Shabbat that rewards, pleases, heals, or nurtures me, so I am commanded on a Shabbat when it doesn’t strike my fancy. So when that auction rolls around each year, I don’t really suffer serious pangs of temptation. I go to shul, which might even happen to be tedious that particular Shabbat, but which offers me that which I could not buy for a bid of a hundred million dollars anywhere—community, family, faith, history, and a strong sense of myself.

There is something, too, about the power of habit and routine, regimentation and fixed parameters—stodgy old words—that I increasingly have come to appreciate. There are some things that spontaneity simply cannot offer—a steadiness and stability which, at its very least, has the emotional reward of familiarity and, at best, creates the possibility of investing time with special meaning, experience with special value, and life with a moment of transcendence.

And that goes for feelings, too. Those occasional Shabbat dinners when I am just not in the mood? When I don’t feel like blessing anyone? Simply, I must be there. Involuntarily, almost against my will, a better mood overtakes me.

I find it fascinating that the Rabbis * of the Talmud speak of kavannah as the emotion that should accompany performance of ritual. Kavannah means intent, or directed purposefulness, rather than spirituality. Even in those more God-oriented times, the Rabbis knew you couldn’t always drum up feeling. Try, they said, but it’s all right, too, if it doesn’t come. Often, meaning and feeling will come after the fact, and not as a motivating force.

While it may sound sacrilegious, one can experience a beautiful Shabbat without thinking a great deal about God. Peak for a Jew does not always mean holy or having holy thoughts. Rather ordinary experiences often become sublime because of the special aura created by Shabbat.

On a recent Shabbat, in shul, my peak experience had nothing to do with prayers, God, Shabbat, or the Torah. As we all stood to sing a prayer toward the end of the service, my eye caught sight of Henri V. holding his two-year-old granddaughter Jordana in his arms. In that same line of vision, twenty rows ahead, I saw Lou B., whose wife was just recovering from surgery, holding his two-year-old grandson Jeremy in his arms. For a few seconds I felt a surge of spirit, a misting of the eyes, a moment of joy in the heart. For me that was Shabbat.

My peak experience the week before (and I don’t have them every week) was even more “unholy.” Three of our children had friends for Shabbat lunch. After zemirot and before the closing Grace, Moshe and two of his yeshiva high-school friends reviewed their terrible pranks of yesteryear. For an hour at the Shabbat table we all laughed over their antics. It wasn’t very “Shabbosdik,” but neither could it have happened at any other time—the warmth, the closeness, the leisure...

No system that engages a variety of human beings can be absolutely perfect. But, to the average Orthodox Jew, Shabbat comes very close to perfection. It is a day of release and of reenergizing; a day of family and of community; of spirit and of physical well-being. It is a day of prayer and of study; of synagogue and of home; a day of rest and self-indulgence; of compassion and of self-esteem. It is ancient, yet contemporary; a day for all seasons. A gift and a responsibility. Without it I could not live.

Activities Proscribed on Shabbat

The Shabbat laws we observe today are a fine example of how Jews have remained tied to the Torah even as we have enlarged its literal mandates. The Torah enjoins us to set aside a day of rest, to remember both divine creation of the world and the Exodus. But it gives us very few cues as to what shape the day takes. In fact, the Torah explicitly forbids activities in three broad categories: leaving one’s place (EXOD. 16:29); kindling fire (EXOD. 35:2-3); and engaging in work (EXOD. 20:10; DEUT. 5:14). But what does leaving one’s place mean? And what is work?

The ancient Rabbis, in setting down the oral tradition of generations before them, have defined the day for us. Work is understood to be all those activities that were associated with building the sanctuary in the desert, and include the following categories:

I. Growing and preparing food

1. Plowing

2. Sowing

3. Reaping

4. Stacking sheaves

5. Threshing

6. Winnowing

7. Selecting out (as, for example, the chaff)

8. Sifting

9. Grinding

10. Kneading

11. Baking (cooking)

II. Making clothing

12. Sheep shearing

13. Bleaching (washing)

14. Combining raw materials

15. Dyeing

16. Spinning

17. Threading a loom

18. Weaving

19. Removing a finished article

20. Separating threads

21. Tying knots

22. Untying knots

23. Sewing

24. Tearing

III. Leatherwork and writing

25. Trapping an animal

26. Slaughtering

27. Flaying skins

28. Tanning

29. Scraping

30. Marking out

31. Cutting

32. Writing

33. Erasing

IV. Providing shelter

34. Building

35. Demolishing

V. Creating fire

36. Kindling a fire

37. Extinguishing a fire

VI. Work completion

38. Giving the “final hammer stroke,” that is, completing some object or making it usable

VII. Transporting goods

39. Carrying in a public place

In order to preserve the spirit of the Sabbath and to prevent its violation, the Rabbis specified three other prohibited categories.

1. Muktzeh—things that are not usable on Shabbat (such as work tools) should not be handled.

2. Sh’vut—an act or occupation that is prohibited as being out of harmony with celebration of the day. For example, if an act is prohibited to Jews on Shabbat, then a Jew may not ask a non-Jew to do it for him. (However, on occasion there are ways of getting around this latter restriction—see p. 37.)

3. Uvdin d’chol—(weekday things). Some activities are “weekday” in spirit even though they do not involve direct labor or prohibited work. Discussing business or reading papers from the office are prohibited on these grounds. Similarly, most sports are considered uvdin d’chol even though they are technically permissible, as, for example, when tennis is played inside an area enclosed by an eruv. (An eruv halachically transforms public areas into private domain. Thus, technically, one is permitted to carry racquet and ball on a tennis court located within the eruv area. But all that exertion and sweat—it’s uvdin d’chol.)

Beyond the thirty-nine prohibitions and the three rabbinic categories, there was also the very large principle of “the honor of Shabbat,” creating a special spirit of the day as the Torah intended. Rabbis of the Talmudic times and of later generations took this principle most seriously, and they proceeded to do everything in their interpretive powers to set aside the Sabbath from the weekday.

Thus, even after the oral law was finally committed to writing (the Talmud, sixth century), the process of defining the Sabbath day continued, including the addition of relevant prohibitions. These were all part of the attempt to remain faithful to tradition and create a special day. Today, we observe a variety of restrictions on Shabbat: no turning on electricity (which is considered a form of kindling fire), no use of television, radio, telephone, vacuum cleaner, food processor, public transportation, or automobile; no cutting paper or fabric, sewing, mending, laundry, writing, playing a musical instrument; no home repair jobs, arts and crafts, sports activities of a certain type, or business activity of any sort; no cooking, baking, squeezing a sponge, opening sealed mail, pushing electric buttons such as doorbell or elevator; no shopping.

There is some variation in practice. For example, some Orthodox Jews will not play tennis, but will play catch in an area that has an eruv. Some will set their dishwashers on a Shabbos clock; others would not wash dishes even by hand, unless they are needed for the next Sabbath meal.

There are certain apartment buildings and even Orthodox synagogues where the elevator is pretimed, that is, it stops at each floor automatically, so that no one has to operate it; and there are some people who will not use these Shabbos elevators, as they are called. Some Orthodox Jews will tear foil, toilet paper, and so forth. Some will open paper wrappings of food. Some will do neither, and will therefore pretear any sort of paper and open all boxes and cans of food on Friday afternoon before sundown.

The Rabbis interpreted not leaving one’s place as not going out of the city limits beyond a distance of two thousand cubits. A cubit i...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Acknowledgments

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Part I: The Jewish Way

- Part II: Special Stages of Life

- Part III: Celebration and Remembering

- Afterword

- Recipes

- Glossary

- Selected Bibliography for a Home Library

- Index

- Footnotes