eBook - ePub

Messengers of the Lost Battalion

The Heroic 551st and the Turning of the Tide at th

- 416 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The author of Before the Flames and the son of a member of the ill-fated infantry battalion discusses America's 551st Battalion and their heroic, little-known role during World War II's Battle of the Bulge.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Messengers of the Lost Battalion by Gregory Orfalea in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

VII

SPEARTIP

At the Battle of the Bulge

It’s the idea that we all have value, you and me, we’re worth something more than the dirt. … What we’re fighting for, in the end, is each other.

—Chamberlain, The Killer Angels

1 Huempfner’s one-man war

Milo Huempfner lay in the snow, underneath a turning wheel. He wasn’t sure if he was in France, Holland, or Belgium. He knew he was a long way from Green Bay, Wisconsin. Huempfner, at the tail end of the 551st’s rushed convoy toward the Ardennes forest where the Germans had made a massive gouge in Allied lines, had skidded his truck around an icy bend, throwing stacks of 81mm mortar shell holders known as “cloverleaves” onto the road and himself into a ditch. It looked like the end of the war for Lieutenant Colonel Joerg’s favorite driver. He waited to pass out and pass into heaven. But it didn’t happen. The truck wheel kept turning, and he began to hear a telltale sign of life: gunfire.

Why hadn’t the Colonel chosen Milo to chauffeur him into history? Joerg had left a day earlier than the battalion in a jeep whose driver floored it for 150 miles. To PFC Huempfner—at twenty-six one of the oldest enlisted men in the battalion—that had to be a driver without the finesse it takes to take a turn in winter. Someone who didn’t know what water does to pavement when it freezes. Someone, in short, who wasn’t from Wisconsin.

This was sure to be the biggest battle the 551st had ever gotten itself into, and here he’d been left to bring up the rear. Hadn’t the Colonel remembered roaring off with his dear Milo in Sicily, kicking up the dust, bellowing to the withered olives that he was going to die—all the officers would be getting it, “so let’s live and roar a little, Milo”? Joerg had paid Huempfner the supreme compliment by taking the wheel and being Milo’s driver. The king had switched places with the serf.

But today, December 20,1944, Huempfner wasn’t feeling so exalted. He picked himself up and bumped his sore head on the turning wheel. That halted it, as if stopping a bad fate. He was lost somewhere on the way to the great battle. What else to do but start a little war of his own? Paratroopers were taught to do that, to cause mayhem for the enemy wherever they might land. So what if in this case his chute had not opened in a 3foot drop from a truck?

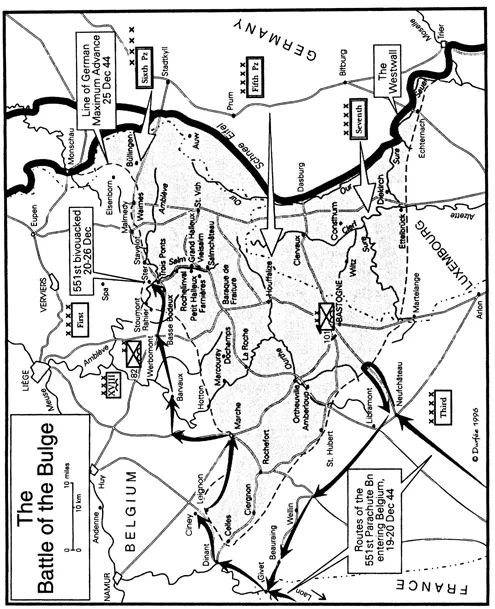

Huempfner didn’t know it at first, but his truck had plunged into a ditch in Leignon, Belgium, outside Ciney near the very tip of the German “bulge” into the Ardennes. The offensive had begun on December 16 with an artillery barrage that seemed to one sergeant in the hard-pressed 99th Division facing the Siegfried Line like “hell broke loose … the earth shook.” Even the Germans themselves were stunned at the magnitude of the opening shelling: “The earth seemed to break open. A hurricane of iron and fire went down on the enemy positions with a deafening noise. We old soldiers had seen many a heavy barrage, but never before anything like this.”1

In seven days, stopped here by small bands of American paratroopers trucked hurriedly into the Ardennes, there by clumps of American engineers who blew up bridges in their faces, the Germans had still managed by December 23 to thrust their forces 65 miles west of the Siegfried Line across three rivers and through a dense fir forest until they approached Ciney. In good times, the German Army could have driven in a few hours to the fourth river, their primary objective before Antwerp, the Meuse. They would spend a month trying, against a largely American defense outmanned at the start 3 to 1 in foot soldiers, and 7 to 1 in artillery. The German final juggernaut of the war would get within 3 miles of the Meuse on Christmas Eve, but no farther. They had not counted on other enemies: such as a bitter winter, Europe’s worst in forty years; “those damned engineers,”2 as the spearhead panzer leader would spit out in disgust; the thirsty gas tanks of their tanks, especially the King Tiger; and a little man here and there in the woods with inhuman courage, driven, as courage often is, by fear, like Milo Huempfner of Green Bay, Wisconsin.

Milo’s wrecked truck was one of 180,000 vehicles of the First and Third Armies, many rushed to the Ardennes by General Eisenhower in the first week of the Battle of the Bulge, a staggering logistical mobility that, as much as anything, saved the Allies in their moment of deepest peril in Europe. Or maybe not quite as much as the human cargo of those trucks, and MiIo was only one of eventually 600,000 Americans who fought in the Ardennes. But what a one.

When Huempfner got up and dusted the snow off himself that day in Leignon, he feared that the 551st’s supply sergeant, Clarence Nace, who was jerking to a stop in an empty 6-by-6 truck, would kill him for spilling all those cloverleaf holders for precious mortars and wrecking an equally precious truck. A crowd of townspeople had gathered, mostly women and old men, and Nace got them to help cart the cloverleaves into the good truck. Huempfner was spared execution but was ordered to sit tight with his vehicle until it could be towed.

“If the Jerries come, blow it up,” Nace barked.

One historian would call Huempfner’s last stand in Leignon a “particularly dramatic battle” of the Bulge campaign.3 It would win Milo the highest—and one of very few—individual awards a man of the 551st would get in the war, the Distinguished Service Cross.

Over the course of five days after his slide into a ditch in Leignon, Huempfner would draw on Lieutenant Colonel Joerg’s insistence that each GOYA train to survive in bad conditions alone and at the same time to inflict punishment on the enemy. He would do it with an M-1 rifle—the basic semiautomatic firearm of the U.S. Army—a .45 pistol, two borrowed hand grenades, and a stunning reserve of moxie and self-control that he would never match in civilian life.

He was tempted at first to let the cup pass, however. A lieutenant in a jeep with a driver told him German tanks from the 116th Panzers and 2d Panzers were headed down several of the five roads that intersected at Leignon, and that he’d better get in quick. Huempfner demurred, saying he had to keep watch over his dead truck as ordered. Another jeep with two officers in back of a driver gave him a delayed shiver. Speaking a cultured English, they asked him if any more paratroopers were in the area. Milo said he was the only one, that his unit was far off and had left him for lost. The nervous driver gunned the interrogators north toward Ciney, where Huempfner later learned they were executed as spies.

Without knowing it, Huempfner had run across three German commandos in disguise, sent by an officer British intelligence had labeled “the most dangerous man in Europe,” SS Obersturmbannfuhrer Otto Skorzeny. In his great gamble in the Ardennes, Hitler had tagged three of his most daring special forces commanders to sow confusion and terror behind the lines in the blitz toward Antwerp: SS Colonel Jochen Peiper, spearhead of the 1st SS Panzers westward; Oberst Frederich August von der Heydte, hero of the 1941 Crete drop and now head of the last German parachute attack, Operation Stösser; and Skorzeny.

Hitler personally prized Skorzeny, a 6-foot Austrian with a wicked dueling scar on his cheek who had plucked Mussolini from his captors in northern Italy in a 1943 commando raid and had recently kidnapped the son of Admiral Horthy to keep Hungary from defecting from the Axis. In late October 1944 Hitler had hardly finished welcoming his favorite back from the Hungary escapade when he gave Skorzeny less than five weeks to outfit a special panzer brigade for Operation Greif. Its primary goal, using tanks, jeeps, and trucks disguised with American markings and English-speaking Germans, was to make it to the Meuse River ahead of three panzer armies and seize at least two of three bridges between Liège and Namur.

But the Trojan Horse operation was compromised almost from the start. To Skorzeny’s great consternation, three days after his conference with Hitler, printed orders for a “Secret Commando Operation” came to his in-box, signed by Field Marshal Keitel himself! Some secret. This was potentially one of the biggest “hard copy” botches of World War II. However, when Allied agents retrieved a sheet of the secret orders in November and later plucked another off a wounded prisoner of the 62d Volksgrenadier Division on the first day of the Wacht am Rhein attack, SHAEF discounted it as a ruse.

The first muster of English-speaking volunteers for Skorzeny’s mayhem unit was quite disappointing. Only ten men could speak perfectly with a knowledge of slang (Kreigsmarine sailors, as it turned out); thirty-five others spoke passably, but with heavy German accents; three hundred others were limited to barely more than “yes” and “no.” After the war, Skorzeny remarked acidly that most of his commandos “could never dupe an American—even a deaf one.”4

Intensive language classes helped some. Those with particularly numb tongues if not skulls were taught profanities and slang. The proper response, for example, to a request for a password was, “Aw, go lay an egg.” At final count, Skorzeny had 2,500 men, of which 150 were organized into nine special “jeep teams” outfitted in American uniforms who did everything from cutting telephone wires and creating fake minefield markings to switching roads signs and directing American troops the wrong way.

“Half a million GIs played cat and mouse with each other each time they met on the road,” General Omar Bradley later said. Thus were spawned the now famous quiz shows at the crossroads that could wreak havoc for a man that did not know the name of Betty Grable’s husband (Harry James), the name of President Roosevelt’s dog (Fala), Babe Ruth’s best season home run total (sixty), or the identity of “dem Bums” (Brooklyn Dodgers). Near Saint-Vith, General Bruce Clarke of the 7th Armored Division was arrested by his own troops on December 21, the day the 551st Parachute Infantry Battalion arrived at Werbomont 10 miles to the west. Clark did not help himself when he answered that the Chicago Cubs were in the American League. Omar Bradley barely escaped from one GI who insisted Springfield was not the capital of Illinois. On one occasion, two American soldiers were shot and killed at a crossroads by nervous U.S. sentries.

Indeed, Operation Greif lost eighteen commandos to execution (including the three Huempfner met). Only three of nine jeep teams returned intact to German lines. One team managed to reach the Meuse; in a desperate dash past a British roadblock, the four disguised Germans were blown up by a mine just before the bridge, several miles beyond any approach of their own panzers.

A few days before Christmas Huempfner awoke in his ditch to a sound “like a bunch of freight trains coming—just one hell of a roaring.” It was a column of fourteen Panzer V Panther tanks of the 2d Panzers, along with a Mark VI Tiger, with sixty soldiers of Kampfgruppe Cochenhausen clinging to their armor. Huempfner soaked his truck with gasoline and set it afire. He ran to the Leignon train depot, where the stationmaster, Victor DeVille, against the protests of his wife, hid him, telling the panzer crew that accosted him that there were no Americans in town. Milo barely breathed in the toilet.

Escaping out a back window later, he ran north and came upon a jeep carrying an American captain heading a truck convoy, whom he warned about the German tank column and a 75mm gun it had emplaced to block the road into Leignon. The captain, filled with rumor fluid, quizzed him about his home state, sticking his carbine into Milo’s belly.

“What is the capital of Wisconsin?”

“Madison,” Humpfner retorted.

“What unit are you from?”

“The 551st Parachute Infantry Battalion.”

The captain was not the first man in Milo’s experience to wonder what in the hell that was.

“How do you spell your name?” the man grabbed Milo’s ID bracelet.

Huempfner barely got that out when the roar of a German halftrack up ahead made the captain cut off the interrogation. As he took off north to Ciney, toward which the German “Bulge” was inflating, he shouted, “Good luck, trooper!” leaving Milo to deal with the tanks.

In a short time Huempfner spotted a Red Cross jeep pulling a trailer of Christmas presents barreling south; Milo ran across a field yelling for the driver to watch out, but it was too late. The medic was killed by machine gun fire from the German position. That shooting of a noncombatant, Huempfner later said, riled him enough to start him on his one-man war.

From a hill overlooking Leignon the next day Huempfner watched as four U.S. tank destroyers, with thinly armored turrets open on top, motored southward from Ciney and came under punishing fire from the German 75mm gun. He promptly shouldered his M-1, by luck found some armorpiercing rounds in his ammunition belt, and shot out the heavy gun. He then beat it to the head of the tank destroyers approaching Leignon, warned the commander about the heavy concentration of tanks in town, and volunteered to go back and scout them. He spotted two halftracks guarding the town’s entry, came back, and asked the major for a handful of grenades.

Feverishly heading back to Leignon—all on foot—he climbed up on one halftrack, pulled the pin on a grenade, and laid it on top of the hatch. That blown off, Huempfner dropped a second grenade down the opening, exploding its interior and its occupants. He did the same with two grenades on the other halftrack, and the blast was louder (Milo thought a land mine must have detonated inside). A flock of Germans fled from a nearby barn.

Later Huempfner ambled straight up to a German sentry standing alongside a Mark-VI Tiger tank outside the Leignon church. One of only twenty that fought in the Ardennes (from the 9th Panzer Division), the Mark-VI Tiger I was a 60-ton behemoth with armor the thickness of brick; its 88mm anti-aircraft gun was a fearsome sight to Americans.

“Hi, Mac,” the sentry said, thinking he had the GI cold, swinging his Schmeisser automatic pistol.

Milo quick-drew him and shot him dead. Luckily, the tank crew was absent. Shortly thereafter a Belgian man pointed down the street and whispered “Rat-a-tat-tat!” A German machine gun was firing at the approaching American tank destroyers from a barn window. Milo imagined the gun’s configuration inside and pumped eight rounds of his M-1 through the barn door. The machine gun went silent. He later found it flattened by a tank along the side of the road, figuring the Germans had destroyed the gun while withdrawing and that he had killed some of its crew. By nightfall the giant tanks, chastened by what seemed a ruthless company of U.S. paratroopers, pulled out of town and billeted themselves in the woods, along with an 88mm self-propelled gun. The company had been one man.

Later, with Milo as forward observer, the 2d Armored Division lay a vicious “time-on-target” (TOT) artillery barrage on the woods where the Panthers and Tigers hid—a fifteen-second saturation salvo of many guns at once that smashed them where they sat.

Along with Milo Huempfner on his risky rounds was a fourteen-year-old Belgian boy named Paul, who finally entreated the exhausted trooper in schoolboy English, “Meelo, it’s dark and getting cold. Let’s go to Grandma Gaspard’s and get warm.” There Huempfner met the astonished townspeople, who told him most of the men of the village had been hauled off to German labor camps years before.

On Christmas Eve the villagers of Leignon asked their protector to watch the church while they held a midnight Mass, which Milo graciously did. He remembered the evening with wonder years later:

When we got to the church I went up and opened the door, and I had my cocked .45 in my hand, and there looking startled was the priest. He said, “Entrez, Meelo.” They just had two little candles burning on the altar for light. I let them all go in past me and then I closed the door and stood guard outside. After Mass, the people all came to me and thanked me for standing guard. “Merci beaucoup,” they each said. Then they walked back through the town humming “Silent Night” very quietly, back to Grandma Gaspard’s place. There were probably about fifteen people altogether. Inside on a table they had a little Christmas tree about 3 feet high with no decorations at all. But to me it was more beautiful than if it had been 40 feet high and decorated with a million shiny things.

On Christmas Day 1944, Huempfner heard the booming of an 88mm gun from the forest nearby; from a footbridge outside town he saw the four tank destroyers and many U.S. soldiers of the Combat Command B of 2d Armored, and soon realized that town was surrounded by friendly forces. On the way back to Leignon, on an impulse he went to a barn and discovered Germans hiding inside. He immediately took into custody eighteen German soldiers, marching them back to the 2d Armored, and informed a commander of the Panther Tiger hiding place.

A pair of German binoculars hanging from his neck, Huempfner was immediately under suspicion of his own troops. A 2d Armored sergeant challenged him: “What is your outfit?” He told them he was with the 551st.

“What division is it in?”

There Milo was stumped. “Well, we are a separate battalion and don’t belong to any division.”

The sergeant’s eyes squinted to slits.

“Sure, pal. What is the password for this sector?”

Huempfner had no idea. He was immediately disarmed and told that a Belgian civilian had informed the 2d that a German straggler had been holed up in the town for days. Milo protested, but clearly they took him now for a spy. His German name didn’t help any. Some MPs drove up in a jeep with a lieutenant, and Milo begged them to take him back to Leignon so he might plead his case. They did, warily, keeping him apart from his weapons and essentially under arrest. He directed them to his burnt-out truck and pointed to the “551st” painted on the bumper. He found Paul, who translated for him in a heated debate with Victor de Ville, the stationmaster who had hid him.

After a humiliating day, his guards began to relent. They took him to the 2d Armored’s headquarters in a schoolhouse in Ciney, where a tall man emerged. He was Lieutenant Colonel Joseph Clema, the division’s provost marshal, wearing a turtleneck sweater. He eyed the PFC head to toe.

“Well, how many did you get?” Clema dropped.

“I was too busy to count,” Huempfner exhaled, cracking a smile for the first time in days.

Clema laughed: “A man could get himself killed doing all that by himself.” Huempfner nodded, and was directed t...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- I THE OLD MEN RETURN: EUROPE, AUGUST 1989

- II HELLO, EARTH!: TRAINING TO BE AIRBORNE

- III PANAMA: THE FIRST (SECRET) MISSION

- IV FOREBODING: THE NIGHT JUMP DROWNINGS AT MACKALL

- V WAR AT LAST: OPERATION DRAGOON INTO SOUTHERN FRANCE

- VI HOLDING THE CRAGS: SKI PATROL IN THE MARITIME ALPS

- VII SPEARTIP: AT THE BATTLE OF THE BULGE

- VIII TALL SNOW: DEATH AT ROCHELINVAL

- IX HOME

- EPILOGUE

- Appendix: Veterans of the 551st Parachute Infantry Battalion Interviewed

- Notes

- Selected Bibliography

- Index