![]()

PART 1

REGIONAL ASPECTS OF

(OR ROUTES TO) A

GLOBALIZING ECONOMY

![]()

CHAPTER 1

THE LIMITED WORLD OF

BUSINESS AT THE END OF

THE 20TH CENTURY

For billions of people on this Earth, talk of the prosperous and growing global economy is just a cruel reminder of their own abject poverty. In terms of trading or communications/information technology, many nations are still barely participating in the supposedly global network. Despite the growing power of the global business network, inequality and lack of effective access to this network still distinguish the international business environment as the 20th century draws to a close.

The decades marking the end of this century clearly represent a “mixed bag.” Some nations, particularly in East Asia but also elsewhere, like Chile, enhanced their global business linkages and gained from rapid economic growth. However, other nations did not fare so well: “Economic decline or stagnation … affected 100 countries, reducing the incomes of 1.6 billion people—… more than a quarter of the world’s population.”1 A recent World Bank book2 summarizes both the overall progress and its unequal global spread:

Developing countries as a group have participated extensively in the acceleration of global integration, although some have done much better than others … there are wide disparities in global economic integration across developing countries…. Many developing countries became less integrated with the world economy over the past decade, and a large divide separates the least from the most integrated…. Countries with the highest levels of integration tended to exhibit the fastest output growth, as did countries that made the greatest advances in integration.

The great challenge of the 21st century is to establish a more truly global international business network, one that can foster a much more comprehensive spread of economic progress than that which the world currently enjoys. The contrast between nations that rapidly grew their economies and trade linkages and those more numerous nations that failed to achieve this progress is discussed in the United Nations Development Program’s Human Development Report (HDR). The 1996 HDR stresses the point that inequality is still the name of the game: “The world has become more polarized, and the gulf between the poor and rich of the world has widened even further.”3 The HDR goes on to detail this widening inequality, stating that “the poorest 20% of the world’s people saw their share of global income decline from 2.3% to 1.4% in the past thirty years. Meanwhile, the share of the richest 20% rose from 70% to 85%. That doubled the ratio of the shares of the richest and the poorest—from 30:1 to 61:1.”4

That the richest 20% of the world’s people amassed more than 80% of global income is a clear example of the “80/20 rule.” This “rule” is well known to apply in many diverse situations. For example, teachers know that 20% of their students will be responsible for 80% of their headaches. Similarly, in business, it is often the case that 20% of customers render 80% of the complaints, special requests, and the like. On the other hand, wise executives and managers know that a special 20% of their customers typically generate more than 80% of their companies’ profits. We will use the 80/20 rule later in our analysis of the current global economy.

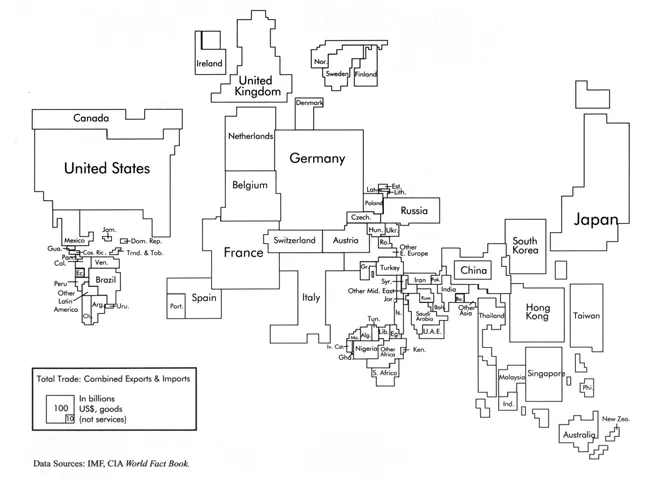

THE WORLD ACCORDING TO TRADE

Let us begin our analysis by looking at the extent of international business as the 20th century draws to a close. A new perspective on the limited nature of the international trading network is provided by Figure 1-1. After many years of exhorting my students to buy an atlas and gain a focus on world geography, I now confuse them by offering this as my map of the world—one with a very different scale from that of a typical atlas. Most atlases attribute power to land mass, using geographic area as the scaling factor. My map is entitled “The World According to Trade” because it scales the world using international trade as the crucial determinant.

How do we measure international trade for this map? We cannot use trade balance as the scaling factor, because some nations, including the United States, run massive trade deficits, and therefore have negative trade balances. It would be very difficult to show a negative number as a scaling factor. Alternatively, exports (what a country sells internationally) or imports (what it buys internationally) could be used as the scaling factor. But exports or imports by themselves would introduce a bias. For example, if we used exports, we would be favoring nations that rely heavily on exports, such as Japan, and be doing an injustice to nations, such as the United States, that are massive importers. More importantly, using exports or imports alone would show only half the picture of international trade, as a nation is participating in international trade if it is buying or selling across national borders. Thus, the most appropriate measure is total trade, calculated as a nation’s exports plus imports.

Figure 1-1 THE WORLD ACCORDING TO TRADE, 1995

What does this new perspective map show us? First, Western Europe is still the center of international business, as it is the largest single bloc in a global trading sense. This dominance is due to intra-European trade, as well as the tremendous trade Europe does with other regions of the world, and has done since the glory days of the Dutch East Indies Company. Note that the legacy of the earlier dominance of that company continues into the modem era, as the Netherlands appears much larger on this map than it does on a geographical map.

Second, although Europe is the largest regional trade bloc, the United States is the largest nation when measured by total trade. This surprises many people, who do not often think of the United States as very savvy about international business.5 But the United States has doubled its exports in less than a decade, and opened up to the world economy in dramatic ways, as was highlighted in this book’s introduction. The fact remains, however, that the major reason we are the world’s largest trading nation is the empirical reality that we import far more than any other nation. Still, one should not miss the big picture: U.S. exports are booming, and have been booming since the dollar started to decline from its peak values of early 1985, making this country the world’s largest exporter as well as largest importer.

The incredible thing is not how big the United States is in this graph, but rather, how big nations such as Singapore, Hong Kong, Switzerland, Belgium, and the Netherlands appear. On an ordinary map, scaled by land mass, these nations would be mere dots. In this trading perspective, we see that these are major nations in the international business network. Singapore, of course, is an extreme case: its population is barely more than 1% of the United States, but it engages in massive trade. Obviously, Singapore’s total trade is less than ours, but not all that much less, for a nation that has such a small land and population base.

The third thing to notice about Figure 1-1 is that there are three major focal points, or massive blocs, in the world trading picture. First, as noted above, Western Europe, at the center of the picture, is an immense trading bloc. Second, the United States is not only the largest trading nation, but is also part of a North American bloc that is noteworthy in this new global perspective. Finally, Japan anchors an East Asian bloc which is remarkably significant in this picture. Figure 1-1 illustrates the often-cited idea that international business essentially comprises a triad of three dominant focal points or regions: Western Europe, North America, and East Asia.

The fourth significant feature of this graph is a key to much of this book. Ever since the Cold War ended with Gorbachev disbanding the Soviet Union, commentators have talked about the end of the East-West divide. However, this new trade perspective makes it apparent that a major divide often talked about during the 1970s still exists. This is the divide between the “haves” in the Northern Hemisphere and the “have nots” in many parts of the Southern Hemisphere. This graph strikingly displays how much of the action in an international business sense takes place among the three blocs of the triad, and thus in the Northern Hemisphere. The contrast between this trade map and a hypothetical map of the “World According to Population” is compelling. A map that scaled the world by population would of course show China and India as the two largest nations, with several other nations in Africa, South America, the Mideast, and South Asia attaining huge dimensions. Thus, in a population sense, the major players are clearly south of the traditional triad.

We truly do have a North-South divide. Roughly 80% of the action, whether we define action in terms of total income, trade, or wealth, resides in the nations of the triad, and thus, in the Northern Hemisphere, north of the Tropic of Cancer. By contrast, most of the world’s people reside in nations near or south of the Tropic of Cancer, often in the Southern Hemisphere or equatorial regions. Notably, the areas in which population is expected to explode are these same equatorial or southern nations, as we will see in Chapter 3. This picture is key to understanding the limited extent of international business as the 20th century draws to a close.

In his acclaimed book, Borderless World,6 the brilliant Japanese consultant and erstwhile politician, Kenichi Ohmae, talks about business opportunities in a world where national borders have become less important. Capital, goods, and people flow with low cost and rapid speed around the world. Although Ohmae’s vision of a borderless world is enticing, a critical reader will notice he only talks about nations in the traditional triad. Hardly a mention is made in the entire book of Africa or the teeming populations of South and Southwest Asia. The world of capital and labor mobility may be borderless, but it exists only among a handful of the very richest nations. Paul Kennedy, in his prescient book, Preparing for the Twenty-first Century, more completely develops this comment on Ohmae’s vision.7

One of my main goals in this book is to put the 80% of the world’s people located outside the wealthy traditional triad back in the vision of a borderless world. Through their own actions and policies, as well as a win-win strategy on the part of global business leaders, these people can become very much a part of the international business network as we move into the 21st century. To continue to ignore them is not only a human tragedy for these populous but poor nations, but also a tremendous lost opportunity for businesses that hope to expand. Global expansion is indeed the catchphrase of the 1990s. However, very few firms think about regions such as Africa and South Asia when they use the term global.

THE NEW FIRST, SECOND,

AND THIRD WORLDS

It would be sheer madness to try in this book to provide detailed numerical analyses of every nation, or even, for that matter, of the almost 200 that participated in the 1996 Centennial Olympic Games in Atlanta. Thus, I created a “master spreadsheet” to help us analyze the international business environment in an efficient manner. I chose a subset of the world’s countries, attempting to capture the great majority of global production, trade, and population. I also included those nations deemed most exciting for future business opportunity. Thus, we will examine more closely about one-fourth of the world’s nations, grouped into three categories, which roughly translate to a new vision of the First World, the Second World, and the Third World.

The First World is captured by a construct very similar to the traditional triad of Western Europe, East Asia, and North America. I term our new First World the ITN. I first used this term to signify industrialized trading nations—those nations that are prominent in total trade, as portrayed in Figure 1-1. However, these nations are also distinguished by being linked in a global information technology network. Thus, the ITN is our modern-day notion of the traditional triad, comprising 26 nations that conduct the bulk of world trade and contain the vast majority of the world’s information technology resources.

Seventeen of the twenty-six ITN nations are in Europe: the current fifteen members of the European Union, as well as Switzerland and Norway. These two wealthy nations opted in the mid-1990s not to join the Union, but do maintain very favorable trade relations with the Union through their membership in the European Free Trade Area (EFTA).

The North American part of our ITN construct comprises only two nations: the United States and Canada. Although Mexico is in the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), it is not included in our ITN as yet, because it is at a much lower level of economic development than its two NAFTA partners.

Finally, the East Asian/Pacific component of the ITN is made up of seven nations. Three are clearly wealthy: Japan, New Zealand, and Australia. Note that Australia and New Zealand are two exceptions to the general rule that Southern Hemisphere nations are poor. The other four nations are the “little dragons” or “little tigers” of East Asia, the aptly termed newly industrialized countries (NICS). These nations are South Korea, Taiwan (which calls itself the Republic of China, but which the mainland Chinese call the Province of Taipei), Singapore, and Hong Kong. Hong Kong was politically subsumed into the Peoples’ Republic of China in 1997, but it continues as a separate economic system and maintains its own economic accounts, so we count it separately here. Although small in land area and fairly small in population, we saw earlier that they are major influences in “The World According to Trade.”

Hence, in total, the ITN, the world’s economic first tier, is made up of 26 nations: 17 in Europe, two in North America, and seven in East Asia or the Pacific. In the days of the Cold War, people would think of something very similar to our ITN as the First World. The Soviet Union and its allied communist nations would be considered the Second World, and the poor, developing countries as the Third World. The end of the Cold War marked the collapse of the traditional Second World, which declined as an economic bloc as the Soviet Union disbanded its empire.

Notably, the Soviet Union was falling to Third World status even before it broke apart. Indeed, Paul Kennedy, in Preparing for the Twenty-first Century (p. 235), summarized the situation facing the Soviet empire as follows: “Overall, the economy and society were showing ever more signs of joining the so-called Third World than of catching up with the First.” The U.S.S.R. was increasingly falling behind the industrialized capitalist nations; thus, Gorbachev chose to disband the failing communist economic system in the hopes of creating a new structure for an eventual First World economy. However, this massive economic transition to a new system resulted in the economies of the former Soviet Union suffering massive dislocation. The economic upheaval pulled these nations down to economic levels that truly reflect a Third World status.

Russia’s economic decline has been extreme. A special box in the Human Development Report 1996, entitled “Russia—into reverse” (p. 84), supports the claim that Russia has fallen into the Third World during its transition toward capitalism:

Since 1991 Russia’s growth and human development have plummeted. Deep recession and hyperinflation sharply increased unemployment and poverty and exacerbated income inequality. Life expectancy, mortality and morbidity have worsened dramatically. Russia is now struggling to rebound from this downward spiral…. In 1991-94 average real wages dropped by more than a third, and agricultural wages by more than half…. In early 1995 the minimum pension was only about 30% of subsistence income. … The Russian education system is also deteriorating.

Russia and ...