- 400 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Strategic Planning

About this book

In today's complex business world, strategic planning is indispensable to achieving superior management. George A. Steiner's classic work, known as the bible of business planning, provides practical advice for organizing the planning system, acquiring and using information, and translating strategic plans into decisive action. An invaluable resource for top and middle-level executives, Strategic Planning continues to be the foremost guide to this vital area of business management.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

III Key Considerations in Planning

7 Alternative Planning Postures, Cognitive Styles, and Values

In this part of the book each of the major elements in the strategic planning process will be examined. The elements treated and the sequence of analysis are shown in the chapter headings. For each there will be presented the nature of the element and major considerations the practitioner should have in mind in completing that stage. In contrast to the discussion on alternative designs for strategic planning presented in Chapter 4, the focus in this part of the book is on doing planning.

The following analysis of doing planning should be considered in light of previous discussions. To this perspective this chapter adds three important additional background considerations: alternative planning postures, differing cognitive styles, and personal values, that managers bring to the planning process. All have an underlying and significant impact on how planning is done.

Alternative Planning Postures

Three fundamentally different planning postures were discussed in Chapter 1, namely, intuitive-anticipatory planning, formal strategic planning, and informal, day-to-day problem resolution. Other planning postures should now be added to this list.

ENTREPRENEURIAL OPPORTUNISTIC PLANNING

In this approach the central focus is on finding and exploiting opportunities. The manager using this approach is constantly searching the environment for new opportunities in both old and new markets, new products, and/or new business ventures. Managers adopting this planning mode are said to thrive on environmental uncertainty and are willing to make high-risk decisions.1

This planning pattern is usually found among managers of very small organizations. But, as Robert McNamara pointed out in the following statement,

I think that the role of public manager is very similar to the role of a private manager; in each case he has the option of following one of two major alternative courses of action. He can either act as a judge or a leader. In the former case, he sits and waits until subordinates bring to him problems for solution, or alternatives for choice. In the latter case, he immerses himself in the operations of the business or the governmental activity, examines the problems, the objectives, the alternative courses of action, chooses among them, and leads the organization to their accomplishment. In the one case, it’s a passive role; in the other case, an active role…. I have always believed in and endeavored to follow the active leadership role as opposed to the passive judicial role.2

INCREMENTAL MUDDLING THROUGH

Lindblom was the first person to articulate this planning posture.3 Managers adopting this planning pattern do not have distinct long-range objectives but develop them in the process of evaluating policy alternatives. Only those policy alternatives that differ incrementally from existing policies are considered, only a small number of policy alternatives are considered, and only a restricted number of consequences for each policy alternative are analyzed. The problem is continuously analyzed and redefined and decisions to deal with it are made in small, incremental steps never too far from the status quo. A “good” policy decision is not one that meets the test of rigorous analysis but rather is one that analysts of the policy agree on. The approach is remedial and geared more to correcting present imperfections than to formulating strategies to meet specific objectives of a challenging nature. This is a reactive in contrast to a proactive stance. Managers following this planning pattern adopt a wait and see attitude. They constantly churn the evaluation process until agreement is reached that a prospective move is acceptable.

THE ADAPTIVE APPROACH

In this approach managers make a strategic decision and then modify it through successive decisions. This procedure involves a successive narrowing and redefining of the basic decision.4 To illustrate, a manager may decide that to achieve a desired sales level the firm must expand beyond current products and markets. Once the decision to expand is made the next task may be to answer the question: Shall we expand through acquisition or in-house new product development? If the answer is to expand through acquisition the next question may be: Shall we acquire a large company or several small companies? If the answer is a large company: What products must the company produce? The analysis thus proceeds with a cascade of decisions and appropriate feedback between the stages.

VARIATIONS AMONG AND MIXING OF PLANNING POSTURES

This list does not exhaust the types of planning postures that exist in both theory and practice but it does show clearly that there are a number of fundamentally different possible approaches to planning. Why discuss such alternative planning patterns here? The answer to this question is that very few organizations, especially the larger ones, rely on any one of these planning patterns, including the formal strategic planning model. In practice there is a mixture of these planning models in organizations. For example, in the infancy of most organizations the entrepreneurial opportunistic model is likely to be dominant, aided by the intuitive-anticipatory posture. In the more mature stages of a large company the formal strategic planning model is likely to be predominant although one may find the entrepreneurial opportunistic approach to be dominant in one or more divisions. The incremental muddling through posture may be adopted in the development of basic company missions and purposes. The adaptive approach is often followed along with formal systematic planning, especially with respect to a major strategic decision. So, these different modes can be found in the same company at the same time. One or another may be used by top management in contrast to the divisions; different divisions may use different approaches; and different planning issues may be addressed with different planning models.

Cognitive Styles

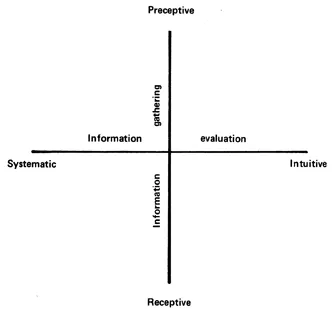

Managers differ significantly in the way they gather and evaluate information. This factor in turn will naturally have a major bearing on how they do planning. McKenney and Keen developed a model of cognitive styles, shown in Exhibit 7-1, that is very helpful in explaining different managerial approaches to planning.

There are two broad types of thought processes used in information gathering, according to McKenney and Keen. One is preceptive and the other receptive. By information gathering is meant “the processes by which the mind organizes the diffuse verbal and visual stimuli it encounters.”5 The result is information.

Preceptive information gatherers begin with a set of patterns, systems, or concepts about how to relate data. They look for patterns and relationships in the data and for facts that fit their mental concepts. They jump about from one set of data to another looking for patterns. Their eyes are more on the forest than the trees in it.

Receptive information gatherers, on the other hand, are very attentive to details. They focus on and ponder individual facts and clues without trying to fit them into conceptual patterns. They are more concerned with individual facts per se than their relationships with one another. They suspend judgment, avoid preconceptions, and insist on a complete examination of all the data available before coming to a conclusion.

As Exhibit 7-1 shows, individuals differ not only in the way in which they gather information but also in the way in which they evaluate it. At one extreme are intuitive thinkers. They avoid committing themselves until the last moment of decision. They continuously search for new information, keep redefining the problem, jump around from one set of data to another, constantly examine alternative solutions, and in effect keep reinventing the wheel. In evaluating the data they depend on hunches and cues in reaching conclusions.

EXHIBIT 7-1: A Model of Cognitive Styles Used in Gathering and Evaluating Information. (Source: James L. McKenny and Peter G. W. Keen, “How Managers’ Minds Work,” Harvard Business Beview, MayJune 1974, p. 81.)

Systematic thinkers have different characteristics. They examine the available information about a problem in a structured fashion. Their solution to a problem proceeds logically, step by step. Alternatives are examined in each step and discarded quickly as the analysis moves toward resolution. They search for a rational method to solve a problem and defend the final solution on the basis of the rationality of the method used.

Cognitive Styles and Planning

The significance of Exhibit 7-1 for this chapter is that different people approach planning problems in fundamentally different ways. Also, certain planning problems that are encountered in an organization will respond more readily to one or another of the cognitive styles.

For example, intuitive-preceptive thinkers are more likely to excel in problems that are elusive or difficult to define, such as specifying basic company missions and purposes. Systematicreceptive thinkers, on the other hand, excel in dealing with problems responding best to quantitative models, such as inventory control or production scheduling.

McKenney and Keen gave a problem of decoding a ciphered message to both systematic and intuitive thinkers. The intuitive subjects solved the problem—“sometimes in a dazzling fashion.” None of the systematic thinkers solved the problem. In this particular case, “there seemed to be a pattern among the intuitives: a random testing of ideas, followed by a necessary incubation period in which the implications of these tests were assimilated, and then a sudden jump to the answer.”6

An important, but not unexpected, finding of the research reported here is that most people apply their preferred style to all problems. They fit facts and problems to their particular mental processes rather than changing cognitive styles to fit facts and problems.7 Only a minority of people in the research of McKenney and Keen appeared to change cognitive styles. This finding partly explains some of the reasons for antiplanning biases in formal planning. It also underscores the point that different levels of strategic planning, and different problems, need the application of different cognitive styles.

Each of the styles discussed here is superior for a particular type of problem. The systematic thinking style has definite strengths in specialized tasks. So, too, does the intuitive style. McKenney and Keen stress the point that “the intuitive mode is not sloppy or loose; it seems to have an underlying discipline at least as coherent as the systematic mode, but is less apparent because it is largely unverbalized.”8

Recent brain research has concluded that systematic, so-called logical thinking takes place in the left hemisphere of the brain. Here is where information is processed sequentially in an orderly way. The right side of the brain, in sharp contrast, is specialized for dealing with emotions, processing information simultaneously, and evaluating information in a relational, holistic fashion. These two brain hemispheres correspond, of course, with the systematic thinker (left side of the brain) and the intuitive thinker (right side of the brain).9

Mintzberg has concluded that managers think on the right side of the brain and planners on the left side,10 an oversimplification, to be sure. Right hemisphere thinking probably is more important at the top of the organization than at the bottom. One major reason for this is that the higher one goes in an organization and the more difficult the problem is, the fewer are the available quantitative facts that bear upon it. The more important is the intuitive element in the final solution. Harlan Mills expressed this point well:

There is a curious natural law in business that places a premium on managerial imagination—The Bigger the Problem the Fewer the Facts. This law manifests itself in the necessary paradox of the “scientific foreman and intuitive president.” Many problems at the supervisor’s level can be quantified, analyzed and optimized down to the last few percent-problems in production scheduling, make-or-buy, even allocating salemen’s time to customers. But most problems at the president’s level involve such intangibles that any decision at all takes courage. For instance, the problems of whether or not to build a plant, or how to build the plant, are of completely different orders of magnitude.

Thus, this simple law places increasing emphasis on the art of sensing essentials early, of drawing inferences from barely sufficient information. For example...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- I Nature and Importance of Strategic Planning

- II Organizing for Strategic Planning

- III Key Considerations in Planning

- IV Implementing Plans

- V Evaluating and Reenergizing the System

- VI Applicability of Business Planning Experience in Other Areas

- VII Concluding Observations

- Notes

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Strategic Planning by George A. Steiner in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Management. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.