![]()

Part I

A New Look at the Art of Seeing

LEONARDO DA VINCI

Detail, Study for the Angel’s Head.

Silverpoint pencil on paper.

Biblioteca Reale di Torino.

“There is something antic about creating, although the enterprise be serious. And there is a matching antic spirit that goes with writing about it, for if ever there was a silent process, it is the creative one. Antic and serious and silent.”

JEROME BRUNER On Knowing: Essays for the Left Hand,1965.

![]()

1

Creativity: The Chameleon Concept

As an example of the contradictory nature of accounts of creative processes, the wife of Robert Browning, the poet, reported that “Robert waits for an inclination, works by fits and starts: he can’t do otherwise, he says.” But later, W. M. Rosetti, speaking of Browning’s writing procedures, said that Browning wrote “day by day on a regular, systematic plan—some three hours in the early part of the day.”

F.G. KENYON Life and Letters of Robert Browning,1908.

What on earth is creativity? How can a concept be so important in human thinking, so crucial to human history, so dearly valued by nearly everyone yet be so elusive?

Creativity has been studied, analyzed, dissected, documented. Educators discuss the concept as if it were a tangible thing, a goal to be attained like the ability to divide numbers or play the violin. Cognitive scientists, fascinated by creativity, have produced volumes of bits and pieces, offering tantalizing glimpses and hints, but have not put the parts together into an understandable whole. To date we still have no generally accepted definition of creativity—no general agreement on what it is, how to learn it, how to teach it, or if, indeed, it can be learned or taught. Even the dictionary finesses definition with a single cryptic phrase: “creativity: the ability to create,” and my encyclopedia avoids the difficulty altogether with no entry, even though another admittedly elusive concept, “intelligence,” is allotted a full-length column of fine print. Nevertheless, books abound on the subject as seekers after creativity pursue a concept that seems paradoxically to recede at the same pace at which the pursuers advance.

Drawing on Treasure-Hunt Notes

The trail, fortunately, is at least marked with pointers to guide the chase. Letters and personal records, journals, eyewitness accounts, descriptions, and biographies are in abundance, gathered from creative individuals and their biographers over past centuries. Like clues in a treasure hunt, these notations spur the quest, even though (as in any good treasure hunt) they often seem illogical and indeed frequently contradict each other to confuse the searcher.

Recurring themes and ideas in the notes, however, do reveal some hazy outlines of the creative process. The picture looks like this: the creative individual, whose mind is stored with impressions, is caught up with an idea or a problem that defies solution despite prolonged study. A period of uneasiness or distress often ensues. Suddenly, without conscious volition, the mind is focused and a moment of insight occurs, often reported to be a profoundly moving experience. The individual is subsequently thrown into a period of concentrated thought (or work) during which the insight is fixed into some tangible form, unfolding, as it were, into the form it was intended to possess from the moment of conception.

This basic description of the nature of the creative process has been around since antiquity. The story of Archimedes’ sudden insight, while he was sitting in the bathtub mulling over the problem of how to determine the relative quantities of gold and silver in the king’s crown, has put his exclamation “Eureka!” (I have found it!) permanently into the language as the “Ah-Ha!” of creativity.

A Scaffolding of Stages

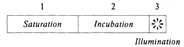

Successive steps in the creative process, however, were not categorized until late in the nineteenth century, when the German physiologist and physicist Herman Helmholtz described his own scientific discoveries in terms of three specific stages (Figure 1-1). Helmholtz named the first stage of research saturation; the second, mulling-over stage incubation; and the third stage, the sudden solution, illumination.

Fig. 1-1. Helmholtz’ conception of creativity.

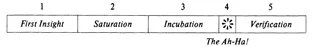

Helmholtz’ three stages were supplemented in 1908 by a fourth stage, verification, suggested by the great French mathematician Henri Poincaré. Poincaré described the stage of verification as one of putting the solution into concrete form while checking it for error and usefulness (Figure 1-2).

Fig. 1-2. Poincaré’s conception of creativity.

Then, in the early 1960s, the American psychologist Jacob Getzels contributed the important idea of a stage that precedes Helmholtz’ saturation: a preliminary stage of problem finding or formulating (Figure 1-3, page 4). Getzels pointed out that creativity is not just solving problems of the kind that already exist or that continually arise in human life. Creative individuals often actively search out and discover problems to solve that no one else has perceived. As Albert Einstein and Max Wertheimer state in the margin quotations, to ask a productive question is a creative act in itself. Another American psychologist, George Kneller, named Getzel’s preliminary stage first insight—a term that encompasses both problem solving (of existing problems) and problem finding (asking new and searching questions).

“I can remember the very spot in the road, whilst in my carriage, when to my joy the solution occurred to me.”

From The Life and Letters of Charles Darwin,1887.

“The formulation of a problem,” said Albert Einstein, “is often more essential than its solution, which may be merely a matter of mathematical or experimental skill. To raise new questions, new possibilities, to regard old questions from a new angle, requires creative imagination and marks real advances in science.”

A. EINSTEIN and L. INFELD The Evolution of Physics,1938.

Max Wertheimer echoed Einstein’s point: “The function of thinking is not just solving an actual problem but discovering, envisaging, going into deeper questions. Often in great discoveries the most important thing is that a certain question is found. Envisaging, putting the productive question is often a more important, often a greater achievement than solution of a set question.”

M. WERTHEIMER Productive Thinking, 1945.

Fig. 1-3. Getzel’s conception of creativity.

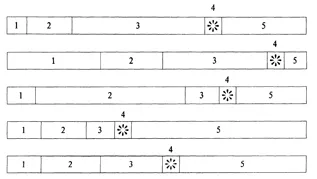

Thus we have an approximate structure of five stages in the creative process: 1. First Insight 2. Saturation 3. Incubation 4. Illumination 5. Verification (Figure 1-3). These stages progress over time from one stage to the next. Each stage may occupy varying lengths of time, as indicated in the diagrams below (Figure 1-4), and the time lengths may possibly be infinitely variable. Only Illumination is in almost every case reported to be brief—a flash of light thrown on the subject. With the notable exception of the Gestalt* psychologists, for whom creativity is an unsegmented process, a single consistent line of thinking for the purpose of solving a whole problem, researchers have generally agreed on the basic concept that creativity involves progressive stages which occur over varying lengths of time.

Fig. 1-4. Variations of the creativity process. Except for the Illumination, which is usually brief, each stage may vary in the length of time required. Also, one project may require repeating the cycle of stages.

Building on this sketchy outline, however, twentieth-century researchers have continued to embellish the elusive concept of creativity and debate its various aspects. Like Alice in Wonderland, it has undergone one transformation after another, thus increasing one’s sense that despite a general notion of its overall configuration, this chameleon concept will forever change before our eyes and escape understanding.

And now the concept is metamorphosing again. Changes in modern life, occurring at an increasingly rapid pace, require innovative responses, thus making it imperative that we gain greater understanding of creativity and control over the creative process. This necessity, coupled with the age-old yearning of individuals to express themselves creatively, has markedly enhanced interest in the concept of creativity, as is shown in the growing number of publications on the subject.

In these publications, one question explored by many writers is whether creativity is rare or widespread among the general population. And the question “Am I creative?” is one we all ask ourselves. The answer to both questions seems to depend on something we usually call “talent”—the idea that either you have a talent for creativity or you don’t. But is it really as simple as that? And just what is talent?

Talent: The Slippery Concept

The drawing course I teach is usually described in the college catalog as follows: “Art 100: Studio Art for Non-Art Majors. This is a course designed for persons who cannot draw at all, who feel they have no talent for drawing, and who believe they probably can never learn to draw.”

The response to this description has been overwhelming: my classes are always full to overflowing. But invariably one or more of the newly enrolled students approaches me at the start of the course to say, “I just want to let you know that even though you’ve taught a lot of people how to draw, I am your Waterloo! I’m the one who will never be able to learn!”

When I ask why, again almost invariably the answer is “Because I have no talent.” “Well,” I answer, “let’s wait and see.”

Sure enough, a few weeks later, students who claimed to have no talent are happily drawing away on the same high level of accomplishment as the rest of the class. But even then, they often discount their newly acquired skill by attributing it to something they call “hidden talent.”

Turning the Tables on this Strange Situation

I believe the time has come to reexamine our traditional beliefs about creative talent—“hidden” or otherwise. Why do we assume that a rare and special “artistic” talent is required for drawing? We don’t make that assumption about other kinds of abilities—reading, for example.

Before embarking on his life as an artist, Vincent van Gogh wrote of his yearning to be creative, which caused him to feel like “the man … whose heart is … imprisoned in something. Because he hasn’t got what he needs to be creative…. Such a man often doesn’t know himself what he might do, but he feels instinctively: yet am I good for something, yet am I aware of some reason for existing! … something is alive in me: what can it be!”

Quoted in BREWSTER GHISELIN, ed. The Creative Process, 1952.

“ ‘ Talent’ is a slippery concept.”

GERHARD GOLLWITZER The Joy of Drawing, 1963.

What about so-called “naturally talented” persons? I believe that these are individuals who somehow “catch on” to ways of shifting to brain modes appropriate for particular skills. I mentioned my own experience in my 1979 book Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain:

“From an early age, perhaps the age of eight or nine, I was able to draw fairly well. I think I was one of those few children who accidentally stumble upon a way of seeing that enables one to draw well. I can still remember saying to myself, even as a young child, that if I wanted to draw something, I had to do ‘that.’ I never defined ‘that,’ but I was aware of having to gaze at whatever I wanted to draw for a time until ‘that’ occurred. Then I could draw with a fairly high degree of skill for a child.”

What if we believed that only those fortunate enough to have an innate, God-given, genetic gift for reading will be able to learn to read? What if teachers believed that the best way to go about the teaching of reading is simply to supply lots of reading materials...