- 400 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

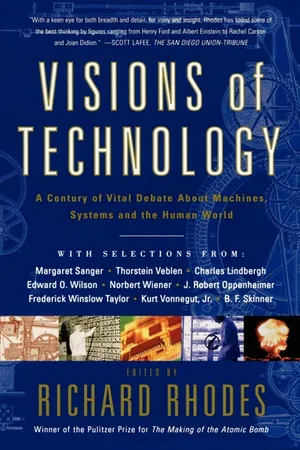

About this book

Technology was the blessing and the bane of the twentieth century. Human life span nearly doubled in the West, but in no century were more human beings killed by new technologies of war. Improvements in agriculture now feed increasing billions, but pesticides and chemicals threaten to poison the earth. Does technology improve us or diminish us? Enslave us or make us free? With this first-ever collection of the essential twentieth-century writings on technology, Pulitzer Prize-winning historian Richard Rhodes explores the optimism, ambivalence, and wrongheaded judgments with which Americans have faced an ever-shifting world.

Visions of Technology collects writings on events from the Great Exposition of 1900 and the invention of the telegraph to the advent of genetic counseling and the defeat of Garry Kasparov by IBM's chess-playing computer, Deep Blue. Its gems of opinion and history include Henry Ford on the horseless carriage, Robert Caro on the transformation of New York City, J. Robert Oppenheimer on science and war, Loretta Lynn on the Pill and much more. Together, they chronicle an unprecedented century of change.

Visions of Technology collects writings on events from the Great Exposition of 1900 and the invention of the telegraph to the advent of genetic counseling and the defeat of Garry Kasparov by IBM's chess-playing computer, Deep Blue. Its gems of opinion and history include Henry Ford on the horseless carriage, Robert Caro on the transformation of New York City, J. Robert Oppenheimer on science and war, Loretta Lynn on the Pill and much more. Together, they chronicle an unprecedented century of change.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Visions Of Technology by Richard Rhodes in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Philosophy & Philosophy & Ethics in Science. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

PhilosophySubtopic

Philosophy & Ethics in ScienceI. THE NEW TECHNOLOGY:

1900–1933

AMERICA IN 1900

MARK SULLIVAN

Journalist Mark Sullivan’s six-volume compendium Our Times chronicles the first decades of the new century from the perspective of the late 1920s. Early in the first volume, Sullivan catalogs what Americans had not yet experienced of technology and social mores at the turn of the century.

In his newspapers of January 1, 1900, the American found no such word as radio,1 for that was yet twenty years from coming; nor “movie,” for that too was still mainly of the future; nor chauffeur, for the automobile was only just emerging and had been called “horseless carriage” when treated seriously, but rather more frequently, “devil-wagon,” and the driver, the “engineer.” There was no such word as aviator—all that that word implies was still a part of the Arabian Nights. Nor was there any mention of income tax or surtax, no annual warning of the approach of March 15 [sic: the income-tax-filing deadline was later moved to April]—all that was yet thirteen years from coming. In 1900 doctors had not yet heard of 606 [i.e., biochemist Paul Ehrlich’s “magic bullet” for syphilis, reported in 1910] or of insulin; science had not heard of relativity or the quantum theory. Farmers had not heard of tractors, nor bankers of the Federal Reserve System. Merchants had not heard of chain-stores nor “self-service”; nor seamen of oil-burning engines. Modernism had not been added to the common vocabulary of theology, nor futurist and “cubist” to that of art. . . .

The newspapers of 1900 contained no menton of smoking by women,2 nor of “bobbing,” nor “permanent wave,” nor vamp, nor flapper, nor jazz, nor feminism, nor birth-control. There was no such word as rum-runner, nor hijacker, nor bolshevism, fundamentalism, behaviorism, Nordic, Freudian, complexes, ectoplasm, brain-storm, Rotary, Kiwanis, blue-sky law, cafeteria, automat, sundae; nor mah-jong, nor crossword puzzle. Not even military men had heard of camouflage; neither that nor “propaganda” had come into the vocabulary of the average man. “Over the top,” “zero hour,” “no man’s land” meant nothing to him. “Drive” meant only an agreeable experience with a horse. The newspapers of 1900 had not yet come to the lavishness of photographic illustration that was to be theirs by the end of the quarter-century. There were no rotogravure sections. If there had been, they would not have pictured boy scouts, nor State constabularies, nor traffic cops, nor Ku Klux Klan parades; nor women riding astride, nor the nudities of the Follies, nor one-piece bathing suits, nor advertisements of lipsticks, nor motion-picture actresses, for there were no such things.

In 1900, “short-haired woman” was a phrase of jibing; women doctors were looked on partly with ridicule, partly with suspicion. Of prohibition and votes for women, the most conspicuous function was to provide material for newspaper jokes. Men who bought and sold lots were still real-estate agents, not “realtors.” Undertakers were undertakers, not having yet attained the frilled euphemism of “mortician.” There were “star-routes” yet—rural free delivery had only just made a faint beginning; the parcel post was yet to wait thirteen years. In 1900, “bobbing” meant sliding down a snow-covered hill; women had not yet gone to the barber-shop. For the deforestation of the male countenance, the razor of our grandfathers was the exclusive means; men still knew the art of honing. The hairpin, as well as the bicycle, the horseshoe, and the buggy were the bases of established and, so far as anyone could foresee, permanent businesses. Ox-teams could still be seen on country roads; horse-drawn street-cars in the cities. Horses or mules for trucks were practically universal;3 livery-stables were everywhere. The blacksmith beneath the spreading chestnut-tree was a reality; neither the garage mechanic nor the chestnut blight had come to retire that scene to poetry. The hitching-post had not been supplanted by the parking problem. Croquet had not yet given way to golf. “Boys in blue” had not yet passed into song. Army blue was not merely a sentimental memory, had not yet succumbed to the invasion of utilitarianism in olive green. G. A. R. [Grand Army of the Republic, an organization established by Civil War veterans of the Union army and navy] were still potent letters. . . .

Only the Eastern seaboard had the appearance of civilization having really established itself and attained permanence. From the Alleghenies to the Pacific Coast, the picture was mainly of a country still frontier and of a people still in flux: the Allegheny mountainsides scarred by the axe, cluttered with the rubbish of improvident lumbering, blackened with fire; mountain valleys disfigured with ugly coal-breakers, furnaces, and smokestacks; western Pennsylvania and eastern Ohio an eruption of ungainly wooden oil-derricks; rivers muddied by the erosion from lands cleared of trees but not yet brought to grass, soiled with the sewage of raw new towns and factories; prairies furrowed with the first breaking of sod. Nineteen hundred was in the floodtide of railroad-building: long fingers of fresh dirt pushing up and down the prairies, steam-shovels digging into virgin land, rock-blasting on the mountainsides. On the prairie farms, sod houses were not unusual. Frequently there were no barns, or, if any, mere sheds. Straw was not even stacked, but rotted in sodden piles. Villages were just past the early picturesqueness of two long lines of saloons and stores, but not yet arrived at the orderliness of established communities; houses were almost wholly frame, usually of one story, with a false top, and generally of a flimsy construction that suggested transiency; larger towns with a marble Carnegie Library at Second Street, and Indian tepees at Tenth. Even as to most of the cities, including the Eastern ones, their outer edges were a kind of frontier, unfinished streets pushing out to the fields; sidewalks, where there were any, either of brick that loosened with the first thaw, or wood that rotted quickly; rapid growth leading to rapid change. At the gates of the country, great masses of human raw materials were being dumped from immigrant ships. Slovenly immigrant trains tracked westward. Bands of unattached men, floating labor, moved about from the logging camps of the winter woods to harvest in the fields, or to railroad-construction camps. Restless “sooners” wandered hungrily about to grab the last opportunities for free land.

One whole quarter of the country, which had been the seat of its most ornate civilization, the South, though it had spots of melancholy beauty, presented chiefly the impression of the weedy ruins of thirty-five years after the Civil War, and comparatively few years after Reconstruction—ironic word. . . .

In 1900 the United States was a nation of just under 76,000,000 people.

MESSAGES WITHOUT WIRES

GUGLIELMO MARCONI, 1901

The twentieth century opened to major invention. Here a faint signal in Morse code inaugurates a new era in world communication.

Shortly before midday [December 12, 1901, in a hut on the cliffs at St. John’s, Newfoundland] I placed the single earphone to my ear and started listening. The receiver on the table before me was very crude—a few coils and condensers and a coherer—no [vacuum tubes], no amplifiers, not even a crystal. But I was at last on the point of putting the correctness of all my beliefs to test. The answer came at 12:30 when I heard, faintly but distinctly, pip-pip-pip. I handed the phone to Kemp: “Can you hear anything?” I asked. “Yes,” he said, “the letter S”—he could hear it. I knew then that all my anticipations had been justified. The electric waves sent out into space from Poldhu [Cornwall] had traversed the Atlantic—the distance, enormous as it seemed then, of 1,700 miles—unimpeded by the curvature of the earth. The result meant much more to me than the mere successful realization of an experiment. As Sir Oliver Lodge has stated, it was an epoch in history. I now felt for the first time absolutely certain that the day would come when mankind would be able to send messages without wires not only across the Atlantic but between the farthermost ends of the earth.

A VERY LOUD ELECTROMAGNETIC VOICE

P. T. MCGRATH, 1902

A writer in Century Magazine imagines how Marconi’s invention might work and descries in the distance the cellular phone.

If a person wanted to call to a friend he knew not where, he would call in a very loud electromagnetic voice, heard by him who had the electromagnetic ear, silent to him who had it not. “Where are you?” he would say. A small reply would come “I am at the bottom of a coal mine, or crossing the Andes, or in the middle of the Atlantic.” Or, perhaps in spite of all the calling, no reply would come, and the person would then know that his friend was dead. Think of what this would mean, of the calling which goes on every day from room to room of a house, and then think of that calling extending from pole to pole, not a noisy babble, but a call audible to him who wants to hear, and absolutely silent to all others. It would be almost like dreamland and ghostland, not the ghostland cultivated by a heated imagination, but a real communication from a distance based on true physical laws.

WILBUR WRIGHT’S AFFLICTION

WILBUR WRIGHT, 1900

When Wilbur Wright wrote engineer and aviation pioneer Octave Chanute for ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Preface to the Sloan Technology Series

- Introduction

- Part I: The New Technology: 1900-1933

- Part II: Depression And War: 1932-1945

- Part III: Postwar Boom: 1945-1970

- Part IV: Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow: 1970–297

- Endnotes

- Bibliography

- Index

- Copyright