- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

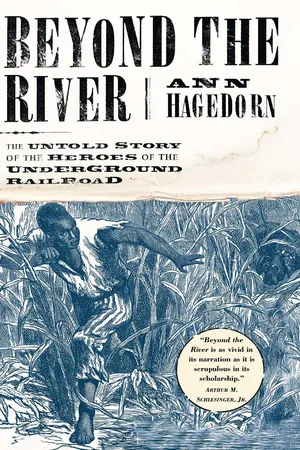

This powerful and necessary tale from Black American history brings to brilliant life the forgotten heroes of the Ripley, Ohio, line of the Underground Railroad.

From the highest hill above the town of Ripley, Ohio, you can see five bends in the Ohio River. You can see the hills of northern Kentucky and the rooftops of Ripley’s riverfront houses. And you can see what the abolitionist John Rankin saw from his house at the top of that hill, where for nearly forty years he placed a lantern each night to guide fugitive slaves to freedom beyond the river.

In Beyond the River, Ann Hagedorn tells the remarkable story of the participants in the Ripley line of the Underground Railroad, bringing to life the struggles of the men and women, black and white, who fought “the war before the war” along the Ohio River. Determined in their cause, Rankin, his family, and his fellow abolitionists—some of them former slaves themselves—risked their lives to guide thousands of freedom seekers safely across the river into the state of Ohio, even when a sensational trial in Kentucky threatened to expose the Ripley “conductors.” Rankin, the leader of the Ripley line and one of the early leaders of the 19th century abolitionist movement, became nationally renowned after the publication of his Letters on American Slavery, a collection of letters he wrote to persuade his brother in Virginia to renounce slavery.

A vivid narrative about memorable people, Beyond the River is an inspiring story of courage and heroism that transports us to another era and deepens our understanding of the great social movement known as the Underground Railroad.

From the highest hill above the town of Ripley, Ohio, you can see five bends in the Ohio River. You can see the hills of northern Kentucky and the rooftops of Ripley’s riverfront houses. And you can see what the abolitionist John Rankin saw from his house at the top of that hill, where for nearly forty years he placed a lantern each night to guide fugitive slaves to freedom beyond the river.

In Beyond the River, Ann Hagedorn tells the remarkable story of the participants in the Ripley line of the Underground Railroad, bringing to life the struggles of the men and women, black and white, who fought “the war before the war” along the Ohio River. Determined in their cause, Rankin, his family, and his fellow abolitionists—some of them former slaves themselves—risked their lives to guide thousands of freedom seekers safely across the river into the state of Ohio, even when a sensational trial in Kentucky threatened to expose the Ripley “conductors.” Rankin, the leader of the Ripley line and one of the early leaders of the 19th century abolitionist movement, became nationally renowned after the publication of his Letters on American Slavery, a collection of letters he wrote to persuade his brother in Virginia to renounce slavery.

A vivid narrative about memorable people, Beyond the River is an inspiring story of courage and heroism that transports us to another era and deepens our understanding of the great social movement known as the Underground Railroad.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Beyond the River by Ann Hagedorn in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Storia & Biografie in ambito storico. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

StoriaSubtopic

Biografie in ambito storicoPART IThe War Before the War

—JOHN PARKER, FORMER SLAVE, FOUNDRY OWNER, INVENTOR, UNDERGROUND RAILROAD CONDUCTOR ON THE RIPLEY LINE

There was a time when fierce passions swept this little town, dividing its people into bitter factions. I never thought of going uptown without a pistol in my pocket, a knife in my belt, and a blackjack handy. Day or night I dare not walk on the sidewalks for fear someone might leap out of a narrow alley at me. What I did, the other men did, walked the streets armed. This was a period when men went armed with pistol and knife and used them on the least provocation. When under cover of night the uncertain steps of slaves were heard quietly seeking their friends. When the mornings brought strange rumors of secret encounters the night before, but daylight showed no evidence of the fray. When pursuers and pursued stood at bay in a narrow alley with pistols drawn ready for the assault. When angry men surrounded one of the [Front Street] houses, kept up gunfire until late in the afternoon, endeavoring to break into it by force, in search of runaways. These were the days of passion and battle which turned father against son, and neighbor against neighbor.

There was a time when fierce passions swept this little town, dividing its people into bitter factions. I never thought of going uptown without a pistol in my pocket, a knife in my belt, and a blackjack handy. Day or night I dare not walk on the sidewalks for fear someone might leap out of a narrow alley at me. What I did, the other men did, walked the streets armed. This was a period when men went armed with pistol and knife and used them on the least provocation. When under cover of night the uncertain steps of slaves were heard quietly seeking their friends. When the mornings brought strange rumors of secret encounters the night before, but daylight showed no evidence of the fray. When pursuers and pursued stood at bay in a narrow alley with pistols drawn ready for the assault. When angry men surrounded one of the [Front Street] houses, kept up gunfire until late in the afternoon, endeavoring to break into it by force, in search of runaways. These were the days of passion and battle which turned father against son, and neighbor against neighbor.

CHAPTER ONE THE KINDLING AND THE SPARK

The town of Ripley lies on land wedged between the Ohio River and a steep, sprawling ridge in a region once known among frontiersmen as the Imperial Forest. Long ago, this vast expanse of green, fifty miles east of Cincinnati, 250 miles south of the Canadian border, and roughly a thousand feet from the Kentucky banks of the Ohio, was rich in hickory and elm, beech and oak, ash and walnut. Sycamores grew to forty-five feet around, so wide, it was said, that a horse and rider could stand in the hollow of a trunk. Thickets of grapevines entangled trees and shrubs in leafy mazes that blocked the sun.

The Shawnee and the Miami traversed these ridges and hollows, tracking bear and buck, ever wary of the panthers and wolves lurking in the shadows. Their villages lined the Scioto and Little Miami rivers, which bordered these verdant hills and fed the Ohio. And at a place where the Ohio narrowed to barely more than a thousand feet and flowed briefly northward, the place where Ripley would one day stand, they crossed the river to Kentucky to hunt more game and sometimes to steal horses. Then, back again, across the river they would come, with the horses they now claimed as their own, followed by the owners they had to outrun.

In the spring of 1804, two cumbrous flatboats moved slowly, like giant, eighty-foot arks, down the river from Mason County, Kentucky, taking most of a day to reach that narrow place where the river runs north, the place so often used for crossings. Colonel James Poage, a forty-four-year-old surveyor from Virginia, had come to claim his thousand acres on the new frontier: Military Warrant No. 14, Survey No. 416, “beginning at two sugar trees and a mulberry running down the river, crossing the mouth of Red Oak Creek to a sugar tree and two buckeyes on the bank of the river.” One boat carried his wife, his ten children, and his possessions; on the other were his twenty slaves, whom he soon would set free.

By then, the Battle of the Fallen Timbers in 1794 and the Treaty of Greenville the following year were forcing the Indians northward and westward, marking the end of their lives in the Imperial Forest and tolling the death knell for much of the forest itself. The forest now stood in the midst of the Virginia Military District, a vast expanse of nearly four million acres between the Scioto and Little Miami rivers, thought to be the richest and fairest part of the region beyond the river. This was the land that, after the Revolution, Virginia refused to cede to Congress.

In those early years of the new nation, the fate of the Northwest Territory, of which Ohio was a significant part, emerged as a hotly contested issue. To whom did the bountiful Western domain now belong? In a nation poverty stricken after the Revolutionary War, every state envisioned revenue gushing from those lands for its own gain. The dense forests, the fertile soil, the abundant game, the river—all of it—conjured images of growth and profit. But a destitute Congress appealed to the states to relinquish their claims for the benefit of all; land sales would fill the government's coffers. The states conceded. Virginia, however, demanded to reserve a tract northwest of the Ohio River to pay its soldiers of the Continental Army. “In case the quantity of good lands on the southeast side of the Ohio, upon the Cumberland River, and between the Green River and the Tennessee River, which have been reserved by law for the Virginia troops of the Continental establishment, should prove insufficient for their legal bounties,” the 1784 deed of cession read, “the deficiency should be made up to the troops in good lands to be laid off between the rivers Scioto and the Little Miami, on the northwest side of the river Ohio.”

During the next three years, warrants issued to hundreds of ex-soldiers were laid upon the “good lands” between the Tennessee and Green rivers. There seemed little need for, or interest in, the reserve north of the river until the summer of 1787, when all of the so-called best lands had been claimed. In August of that year, a bureau opened in Louisville to encouragesurveys into the Ohio territory. The early surveyors, knowing they could profit handsomely, returned from their missions with glowing accounts.

That same year, Congress passed the Northwest Ordinance—the first law in the new nation's history to ban slavery. “There shall be neither slavery nor involuntary servitude in the said territory otherwise than in the punishment of crimes,” the sixth article of the law read. In Ohio, in its early years, slave owners could free their slaves without any liability. Other states, fearing that freed slaves would become wards of the state, required a bond. This new land of the free had particular appeal among those ex-soldiers of the Continental Army who had fought with the cause of liberty in their hearts and after the Revolution saw only hypocrisy in the slavery sanctioned by their home states.

So, by the early years of the nineteenth century, droves of Virginia's veteran soldiers, as well as speculators who had purchased the warrants from soldiers choosing not to move, were hastening to the land beyond the Ohio River, to this El Dorado of the West, a land where no man could be enslaved as the property of another.

Colonel James Poage, the man docking his flatboats, was one of them. Poage had served in the war, first as ensign in 1780 and then as lieutenant of militia in 1782. His title of colonel came out of his trailblazing years as a surveyor. Surveying in the unsettled Northwest was such a perilous job that parties of surveyors often banded together for protection, and when they did, the leader of the group was designated “colonel.” Known for ambitious expeditions, a bold style, and a generous, egalitarian treatment of workers and slaves, Colonel Poage led large surveying bands into the wildest parts of Virginia, Kentucky, Indiana, Illinois, and Ohio throughout the 1780s and 1790s. In exchange for his work—nearly twenty years of it—he acquired parts of what he had surveyed: forty thousand acres, mostly in Virginia, Kentucky, and Illinois. When he retired from surveying, he first claimed land in Kentucky, where he lived in Ashland and then near Maysville, in Mason County. But it was his thousand-acre military warrant on the southernmost edge of the Imperial Forest that he chose for his permanent settlement.

Poage clearly recognized the potential his acreage held for riches from timber, agriculture, and the passing river traffic. But there was something else that lured the colonel, something pulling him to Ripley's shore like the spring sun drawing sap through the trees: He abhorred slavery. This loathing had risen within him during the Revolution and had grown with time, convincing him to renounce his own slaveholding and causing him to become dissatisfied with his life in Kentucky. In Ashland, he was in conflict with the slaveholders in his church, and in Mason County he couldn't bear the presence of slave traders or the sight of slave auctions. Once upon Ohio soil, he freed his slaves. He took apart his flatboats and built shelters from the logs. He called his settlement Buck's Landing.

In the months that followed, Poage renamed his plot, calling it Staunton, after the town in Virginia where he and many of his slaves had been born. Soon he and others tore the vines from the trees, hewed the hickory and beech, the ash and oak, and made paths through the remaining woods. Even the massive sycamores fell, one by one, as they cleared the land to build houses.

The others came slowly, year by year. There was Alexander Campbell, Ripley's first physician, who in 1804 migrated to Ohio from Kentucky, freed his slaves, and settled on Front Street. Born in Virginia and educated in Kentucky, Dr. Campbell was, by most accounts, Ohio's first abolitionist and soon to be one of the state's first two U.S. senators. James Gilliland, a Presbyterian minister ostracized in South Carolina for his antislavery views, arrived in 1805 and settled six miles north in Red Oak. Families from his congregation who shared his views, and friends from his hometown in North Carolina, soon followed and eventually joined him in the abolitionist underground. Thomas McCague, who would one day be a magnate in the nation's pork-packing industry, and his wife, Catherine, would also become active participants in Ripley's secret world, sharing their covert work with Front Street neighbors Nathaniel Collins, a carpenter and Ripley's first mayor; with three of his sons, Theodore, Thomas, and James; with the Beasley brothers, Alfred and Benjamin, both physicians; and with Dr. Campbell. From East Tennessee came Reverend Jesse Lockhart, who worked the Russellville, Ohio, link in the Ripley line, and Reverend John Rankin, whom William Lloyd Garrison would one day call his inspiration and teacher in the cause of ending slavery. Later would come John Parker, the free black abolitionist who distinguished himself by his daring forays into Kentucky to liberate slaves.

In the coming years, the growing community would attract more citizens of conscience whose abhorrence of slavery impelled them to uproot their families and to travel sometimes for months, often over rugged foothills and mountains, to a land they had never seen: Dr. Greenleaf Norton, Dr. Isaac M. Beck, Martha West Lucas, Sally Hudson and her brother John, the Pettijohns, the Cumberlands, and John B. Mahan among others. Some would live to see the end of slavery. Others would die in the struggle against it—casualties of the war before the war.

In 1812, Poage laid out his new town. Four years later, Staunton, population 104, became Ripley. A town farther north had already taken the name Staunton, and so the townsfolk changed theirs to honor General Eleazar Wheelock Ripley, a renowned American officer in the War of 1812. General Ripley had commanded the Second Brigade in the army of General Jacob Brown, for whom Ohio's Brown County had been named.

In the earliest plans for the town, there was always a road running parallel to the river with alleys branching out from it. At first, it seemed, the alleys provided comfortable distances between neighbors. Then, as more and more rooftops winked through the foliage and woodsmoke plumed over the town, horse-drawn wagons ambled along these narrow passages, leaving piles of wood at the side doors and back entrances of the riverfront houses. And as Ripley's double identity took shape, the alleys took on a new life—at night. Perpendicular to the river, they were conduits to the land beyond Ripley—extensions of the river as much as the ravines and streams flowing like tiny arteries around the heart of town. The alleys facilitated swift passage out the back doors of Front Street, up the steep hill behind the town, and onward to other towns and other hills. Dr. Campbell, Rankin, one of Rankin's sons, and others in the underground would build or purchase houses along the alleys.

By the 1830s, the alleys were well worn from the horse-and-wagon traffic of daily commerce and the human traffic that sometimes ran deep into the night. By then, Ripley was one of the busiest shipping points on the Ohio River. Stately brick row houses were replacing log cabins on Front Street. And on the many new streets in town, there were seven mercantile houses, three physicians, two attorneys, several cabinet shops, tan yards, groceries, millineries, shoemakers, wagon and carriage makers, a clockmaker, and a large woolen mill. Along the creeks were flour mills, and on the riverbank was a boatyard where flatboats and steamboats were built. By then, too, Ripley was second only to Cincinnati in the pork-packing industry. Farmers throughout the county brought their hogs to the Ripley market, where the animals were slaughtered and the lard was packed in kegs, the pork was pickled in barrels, and the slabs of cured hams and bacons were piled onto ships and sent east on the river via Pittsburgh or south to New Orleans.

The town was also known, at least among slaves and their masters in northern Kentucky, as a haven into which runaways seemed to disappear. In the early 1830s, a slave named Tice Davids had reached the Ohio River across from Ripley with his Kentucky master trailing so close behind him that Davids had not a second to search the shoreline for a skiff. And so he swam. His master, however, did spend time looking for a boat, and though he rowed swiftly and could see the head and arms of his slave thrashing through the water, he could not catch him. He watched as Davids climbed up the Ripley banks, then lost sight of him. He rammed his boat onto the shore and rushed up the steep bank to Front Street, where he asked everyone he saw about the black man who had just moments ago emerged from the river, clothes heavy with the weight of water. Had no one seen him? He walked the streets and searched the alleys, but he never found his slave. No one he asked in the entire town could recall seeing a man of Davids's description. Frustrated and confused, he returned to Kentucky, where he told everyone he knew that his slave “must have disappeared on an underground road.”

Word of such a road began to spread, and Ripley's position along one of the narrowest bends of the Ohio was soon known among slaves in Kentucky. Many knew that a dry spell rendered the river so shallow that crossing at such a narrow stretch was more like wading a stream than navigating a river. For those who managed to cross at higher water, the network of streams and creeks bordering the town provided pathways away from the river and far beyond it—Eagle Creek, Red Oak Creek, Straight Creek, White Oak Creek, all wide enough for skiffs and even flatboats, depending on the season and the rainfall. The hounds of a slave hunter could not detect the scent of a man escaping by way of water. The streams cut through a complex terrain of hills and dales that could mask the sight of a horse and rider at every undulating curve or hollow. Just as important were the remnants of the Imperial Forest, the dense woods above the town, beyond the hill, and along the creeks—a thicket that, for those who knew it well and did not fear it, gave cover that would foil pursuit.

Also critical to Ripley's appeal as a gateway to freedom were the nearby free black settlements. In 1818, 950 freed slaves from Virginia had settled on twenty-two hundred acres north of town. These men, women, and children had labored for Samuel Gist, a British merchant of exceptional wealth who had died in London a few years before and had stipulated in his will that upon his death the slaves on his vast Virginia plantations would be set free. The proceeds from the sale of his Virginia lands were to be used to buy land in that state for the freed slaves, to build their houses, churches, and schools, and to pay their teachers and ministers. But when his daughters petitioned the Virginia legislature to approve the will, legislators balked at the notion of releasing so many slaves in their state—what would be one of the largest manumissions in the nation's history. No slaveholding Virginian could forget the recent slave rebellions throughout the Western world, sometimes led by bands of free blacks. Some legislators referred to the bloody Haitian revolt in 1791, in which slaves overthrew their white masters. Others spoke of the attempted rebellion of a slave named Gabriel, who enlisted the help of more than one thousand slaves in Virginia in 1800. The legislators cited an 1806 law that required freed slaves to leave Virginia within one year or face re-enslavement. And so the legislators voted to allow the manumission only if the freed slaves moved out of Virginia. Three hundred of the slaves left their homes in Virginia's counties of Hanover, Amherst, Goslin, and Henrico and, under the guidance of Gist's agents, resettled in Brown County, Ohio, in two communities. The remaining fifty came separately, stopping several places on the way and arriving more than a year later.

For slaves south of the river, the Gist settlements were Mecca. Escaping slaves naturally sought out free black communities as hideouts from slave hunters and masters. As the largest free black encampments in the region, the Gist communities increased the runaway traffic through Ripley, the main river town in Brown County. They also intensified the friction between Ripley and nearby towns, where abolitionists were often despised and Gist settlers treated like an Old Testament pestilence. For, despite the antislavery sentiment in and around Ripley, the region, so close to the border of a slave state, was filled with indifference and sympathy for Southern slaveholding. In the summer of 1819, in a Southern Ohio newspaper, an unnamed citizen who called the settlements “camps” wrote to the editor: “Much as we commiserate the situation of those who, when emancipated, are obliged to leave their country or agin be enslaved, we trust our constitution and laws are not so defective as to suffer us to be overrun by such a wretched population. Ohio will suffer seriously from the iniquitous policy pursued by the States of Virginia and Kentucky in driving all their free Negroes upon us.”

A year after the arrival of the Gist slaves, the Missouri Territory sought admission to the Union as a slave state—an issue that at first seemed unimportant to Ripley. If Missouri entered as a slave state, slaveholding interests in the U.S. Senate would have a voting margin over the free states. This would also facilitate the expansion of slavery into the rest of the unorganizedlands of the Louisiana Purchase. The ensuing debate was so bitter as to threaten the life of the Union. Elihu Embree, a Quaker abolitionist from Tennessee, wrote, “Hell is about to enlarge her borders and tyranny her domain.”

A compromise was fashioned and, to balance the slavery scale, Maine entered the Union as a free state. Under the Missouri Compromise, as it was known, slavery would be permitted south of latitude 36 degrees 30 minutes, and prohibited north of that line. Dissolution and war were averted, for the time, but the compromise sectionalized the nation as never before. John Quincy Adams presently called the compromise “the title page of a great, tragic volume.” Newspapers in slaveholding states burst with commentaries ardently defending the institution of slavery. They saw the compromise, which prohibited slavery in a vast portion of the Louisiana Purchase, as a device to minimize the number of slaveholding states. And they claimed that “deluded madmen” were plotting to destroy their world. Abolitionists in slave states lost much of their support and migrated to free states, where antislavery sentiment was building. At the same time, antislavery forces saw the compromise as an indication that slaveholders in Congress—what they called the “slave power”—were shaping national policy and would be the architects of Western expansion. After numerous complaints about slave catchers roaming the banks of the river, Ohio legislators passed a law to punish the mercenaries who invaded the state to hunt down free blacks in order to collect slave owners' rewards for their recapture or to sell them downriver. In response, Kentucky legislators, in violation of the Constitution, passed a law bolstering the rights of slave owners to enter free states and reclaim their “property.”

Along the river, tensions were rising and suspicions growing. The kindling of controversy was piled high. Ripley's role in this borderland war was becoming ever clearer. A single spark might unite Ripley in the cause of ending slavery and resisting the slave power. It came in the form of a Presbyterian minister named John Rankin.

As news of the Missouri Compromise reached Carlisle, Kentucky, where Rankin lived, and nearby Concord, where he preached, Rankin felt the pulse of his community quicken. He sensed the anger in the hearts of slave owners and the frustration among antislavery advocates when he stood at the pulpit seeking to prove that slavery was as great a crime against the laws of God as murder, and arguing that every slaveholder must free his slaves to adhere to the teachings of the Scriptures....

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- CONTENTS

- PREFACEA DOUBLE LIFE

- PART IThe War Before the War

- PART II1838

- PART III Midnight Assassins

- PART IV Beyond the River

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- NOTES

- SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY

- INDEX