eBook - ePub

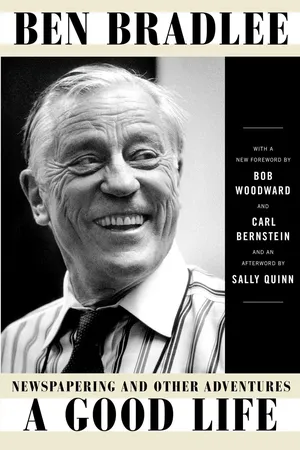

A Good Life

About this book

The classic New York Times bestselling memoir by legendary executive editor of The Washington Post Ben Bradlee—with a new foreword by Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein and an afterword by Sally Quinn.

The most important, glamorous, and famous newspaperman of modern times traces his path from Harvard to the battles of the South Pacific to the pinnacle of success at The Washington Post. After Bradlee took the helm in 1965, he and his reporters transformed the Post into one of the most influential and respected news publications in the world, reinvented modern investigative journalism, won eighteen Pulitzer Prizes, and redefined the way news is reported, published, and read.

His leadership and investigative drive during the Watergate scandal led to the downfall of a president, and his challenge to the government over the right to publish the Pentagon Papers changed the course of American history.

Bradlee’s timeless memoir is a fascinating, irreverent, earthy, and revealing look at America and American journalism in the twentieth century—a “sassy, sometimes eye-poppingly, engrossing autobiography...must reading” (The New York Times Book Review).

The most important, glamorous, and famous newspaperman of modern times traces his path from Harvard to the battles of the South Pacific to the pinnacle of success at The Washington Post. After Bradlee took the helm in 1965, he and his reporters transformed the Post into one of the most influential and respected news publications in the world, reinvented modern investigative journalism, won eighteen Pulitzer Prizes, and redefined the way news is reported, published, and read.

His leadership and investigative drive during the Watergate scandal led to the downfall of a president, and his challenge to the government over the right to publish the Pentagon Papers changed the course of American history.

Bradlee’s timeless memoir is a fascinating, irreverent, earthy, and revealing look at America and American journalism in the twentieth century—a “sassy, sometimes eye-poppingly, engrossing autobiography...must reading” (The New York Times Book Review).

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

ONE

EARLY YEARS

It was a balmy fall day—October 2, 1940.

The scene was a large, messy living room, converted to an office in one of those big, Victorian houses that circle Harvard Square in Cambridge.

The sign on the door read “The Grant Study of Adult Development.” Financed by W. T. Grant, the department store magnate, and run by Harvard’s Health Services Department, the study proposed to investigate “normal” young men, whatever that might mean, at a time when most research was devoted to the abnormal. Dr. Arlie Bock, the first Grant Study director, was convinced that “some people coped more successfully than others,” and the study intended to search for the factors which “led to intelligent living.” The guinea pigs were drawn from consecutive freshman classes at Harvard, a total of 268 men. *

I was one of those guinea pigs, and we were presumed by our presence at Harvard to have shown “some capacity to deal more or less ably with [our] careers to date.” The researchers included internists, psychiatrists, anthropologists, psychometricians, social workers, plus an occasional physiologist, biologist, or chemist.

On that particular afternoon, I was a sophomore, just turned nineteen, a sophomore who had only recently been laid for the first time, sort of. The Depression and a six-month siege of polio had been the sole departures from an otherwise contented, if not stimulating, life.

The news was dominated by the war in Europe. Churchill had just replaced Chamberlain. Some 350,000 British troops had been evacuated from Dunkirk in small boats. FDR had masterminded the gift to Britain of fifty American four-stack destroyers,* and was nearing reelection to his unprecedented third term. Joe DiMaggio was about to hit .350 and win the American League batting title. Gas cost 15 cents a gallon. A luxury car cost $1,400. And Ronald Reagan had just been picked to star in She Couldn’t Say No with someone called Rosemary Lane.

The Grant Study’s social worker later described a classic young WASP, whose family income was $10,000 a year ($5,000 from my father’s salary, $5,000 from my mother’s dress shop), and whose college expenses were paid for by a New York lawyer grandfather. She described my father as “industrious, hard-working . . . interested in nature, trees, birds, antiques, sports and civic things.” My mother was listed as “ambitious and industrious . . . musical and artistic” (which she would have liked), and as “rather of the flighty and artistic type. Very charming and young in her ideas [at forty-four]; almost immature.” That last would have enraged her.

After the physical exam, the doctors noted their guinea pig was 5 feet 11½ inches tall and weighed 173 pounds, with warm hands, cold feet, “marked postural dizziness,” “moderate hand tremor,” “slight bashful bladder,” three tattoos—one on left arm and two on right buttock—“rather short toes” with “slight webbing” between #2 and #3, a double crown in his scalp, and without eyeglasses, freckles, or acne. Blood pressure was 112 over 84. Pulse was 81; respiration, 22. Hair: dark brown. Eyes: brown/green.

The psychometrist made 107 different measurements, including head length (210 mm), head breadth (151 mm), nose height (51 mm), wrist breadth (59 mm), sitting height (95.6 cm), trunk height (60.9 cm), and something called “cephalo-facial” (21.19: 88.9); and made 134 separate psychometric observations: mouth breather (yes), chest hair (absent), thighs (muscular: + + +), buttocks shape (+ +), Fat Dep. Butt. (+), Fat Dep. Abd. (sm), chin (pointed), nasal tip (snub), teeth lost (none), earlobe (free), hands shape (long, square), handedness (right), footedness (right); and concluding medical physical appraisal (normal).

One of the psychologists described her guinea pig as a “very good-looking . . . boy, well-mannered and cultured. He walked into the office with the confident manner of one who knows how to deal with people.” She was especially impressed with how this “quite normal, well-adjusted, and socially adaptable” boy had adapted to four months of leg splints and crutches during his bout with what was then called infantile paralysis. “In spite of being unable to move his legs [for a couple of months] and in spite of one of his friends dying in the same epidemic . . . he never did consider he would be paralyzed. This is a very interesting fact in illness. Do those people who develop a permanent paralysis have as much confidence while they are ill as this boy had?”

But they weren’t all that impressed by much else.

“My general impression of this boy is quite good,” the anonymous psychologist noted. “He probably will not have any trouble socially here at Harvard. His trouble will probably lie in a conflict between his conservative Bostonian raising and his ideas and ideals which are gradually becoming more radical.”

“This boy’s emotional response to things” attracted psychiatrists’ attention. “ . . . he often cries rather openly in a movie . . . he often puts himself right into the shoes of the actors and actresses, and . . . he enjoys this. He states, too, that he has a strong desire and emotional feeling toward [the film] ‘A Foreign Correspondent.’ As a matter of fact, he has seen this picture four times and is looking forward to seeing it again. He feels that a foreign correspondent is one of the most ‘romantic’ and ‘glamorous’ persons that live today. He is looking forward to doing this sort of work. My general impression is that this boy has a rather immature, emotional, and romantic outlook on what he wants to do.”

Six months later I returned for one of many required follow-up sessions, and a new psychologist described someone quite different. “When he came in,” his notes read,

I could easily see that he is mixed up. His principal problem seems to center around the fact that before he came to Harvard he was living in a more or less materialistic world. He had been more a typical American boy—quite athletic, quite popular in school, and doing his work fairly well. But it was not until his freshman year at Harvard that he began to think, particularly in the abstract. Thus, he has more or less changed to a theoretical, philosophical, impractical person, whereas before he was quite materialistic and practical.

This new toy, the philosophical and abstract, has rather confused him. In his confusion, the boy has become rather restless and dissatisfied with Harvard. As a result, he did very poor work in his midyear examinations. Shortly after doing this poor work, he started making plans for stopping school. At three o’clock one morning, this boy suddenly decided to go to Montreal and join the R.C.A.F. He went to talk with those people, and they said they would accept him, but at that time he backed out and came back to Harvard.

However, his restlessness and dissatisfaction continued. He began to wonder why he was here at Harvard; he wondered what kind of a life he was going to lead; and he was generally mixed up with his new plaything—the dealing with the philosophical, abstract and theoretical. Recently, he has gone down to the Navy Yard and found that he can join the Naval Air Force when he reaches 20, which will be August 26 of this year.

The general picture is one of confusion and dissatisfaction with himself and with the results he has been attaining here at Harvard. Entering into this dissatisfaction is his restlessness. He has done several things to overcome his restlessness. There have been times when he has drunk too much alcohol, but this does not satisfy him.

Sixteen months later, on August 8, 1942, “this boy” graduated from Harvard by the skin of his teeth at 10:00 A.M. At noon, I was commissioned an ensign in the United States Naval Reserve, with orders to join the Philip, a new destroyer being built in Kearny, New Jersey. And at 4:00 P.M., I married Jean Saltonstall, the first and only girl I had slept with.

I was not yet twenty-one. I had never been west of the Berkshires or south of Washington, D.C., and I was on my way to some place called the South Pacific, which was not yet a musical.

The education of Benjamin C. Bradlee was finally under way.

As a family, the Bradlees had been around for close to three hundred years, but well down the totem pole from the Lowells and the Cabots. Proper enough as proper Bostonians went, but not that rich, and not that smart. Grandparents who were well off, if not rich. Nice Boston house, not on Beacon Hill, not even on the sunny side of Beacon Street overlooking the Charles River, but on Beacon Street still. One car, no boats, but a cook and a maid, and a stream of governesses before the Depression, plus old Tom Costello to lug firewood up three flights of stairs to the living-room fireplace and to shovel coal into the basement furnace.

Josiah Bradlee (married to Lucy Hall), described as “the poor son of a humble Boston tinsmith” (Frederick Hall Bradlee), was listed among the fifteen hundred wealthiest people in Massachusetts and a millionaire in 1851. One authority wrote: “In spite of his great wealth and standing as a merchant prince . . . never attaining a place among the Proper Bostonians.”

It was said of him, heavily: “If he sent a shingle afloat on the ebb tide bearing a pebble, it would return on the flood freighted with a silver dollar.”

One of his proudest boasts: “In all the 82 years of his busy life he never spent but one night away from Boston. That time he journeyed to Nahant.”

My father was a Walter Camp All-American football player from Harvard, turned investment banker in the 1920s, busted by the Depression in the thirties. Frederick Josiah Bradlee, Jr., son of Frederick Josiah Bradlee, grandson of Frederick Hall Bradlee, all the way back eight generations to Nathaniel Bradley, born in 1631, who got the cider concession in Dorchester, Massachusetts, in 1673, and made sexton in 1680. His job was to “ring the bell, cleanse the meeting house, and to carry water for baptism.”

My father was born at 211 Beacon Street in the Back Bay. After they married, my parents first lived in an apartment at 295 Beacon Street. They bought their first house, a brownstone, at 267 Beacon Street, lived there for twenty-three years, and then moved across the street, back into an apartment at 280 Beacon Street. These were not adventuresome people.

After football, “B” Bradlee rose quickly like all Brahmin athletes of that era from bank runner, to broker, then vice president of the Boston branch of an investment house called Bank America Blair Company. And then the fall. One day a Golden Boy. Next day, the Depression, and my old man was on the road trying to sell a commercial deodorant and molybdenum mining stock for companies founded and financed by some of his rich pals.

There was always the promise of some dough at the end of a family rainbow, as soon as the requisite number of relatives passed on to their rewards. Especially Uncle Tom, whose fortune was so long anticipated, and his wife, the long-lived Aunt Polly. Tom was some kind of cousin to my grandfather, and lived in some institution in western Massachusetts, dressed immaculately in yachting cap, blue blazer, and white flannels, looking through a long glass across green fields for God knows what. Aunt Polly lived at 111 Beacon Street. My father and his two brothers called on her regularly to check her pulse, until she died of old age in her late eighties.

Before the right people died, my father kept the books of a Canadian molybdenum mine for a few bucks; he kept the books of various city and country clubs for family memberships; he supervised the janitorial force at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts—for $3,000 a year. And all through the Depression we lived rent-free, weekends and summers, in a big Victorian house owned by the estate of some distant relatives named Putnam in the woods of Beverly, Massachusetts. Rent-free, provided we kept up the grounds and barns, which “B” did with a passion, and with me when I was around.

This was Beverly, a glorious by-product of the Depression, when my family had the use of two houses, plus two big barns in twenty acres of beautiful woods, on a hill overlooking the bays of Salem and Beverly, less than a mile away. The owners were the trustees of an estate, who wanted to sell when no one wanted to buy. We had lived there, summers in the big house, winter weekends in the cottage, from 1932 until one afternoon in the summer of 1945. “B” and Jo were having cocktails on the big porch which girded the house, when an unknown car drove around the circle by the front door.

“Who’s that, for God’s sake?” Jo asked, according to family legend.

“Beats me,” “B” is said to have replied. “Probably someone looking to buy the place. Been for sale for fifteen years.”

Now for the first time in years, Jo was feeling almost flush. An elderly relative, who had been long forgotten in some convent, had recently been gathered, leaving Josephine $5,000. She announced that she was going to call Harvey Bundy, one of the trustees, and a family friend (also the father of future national security adviser McGeorge Bundy), and offer him the $5,000 for the whole place.

And over my father’s dead body she rose from her chair and she did it. Harvey wouldn’t take $5,000, but by God he would take $10,000, and all of a sudden this gorgeous place was ours. I have nothing but wonderful memories of Beverly, learning a love of the outdoors that has never left me, cutting down each giant beech tree that died in the blight of that time, on the opposite end of a two-man saw with my father and his friends. Burning brush for hours on end, still a uniquely calming and rewarding experience for me half a century later. Climbing trees, collecting butterflies, growing vegetables, playing doctor with my sister’s friends. “B” and I built a backboard in the garage, even though the ceilings were only seven feet six inches high. It taught me to keep backhands and forehands low, and kept me busy on rainy days.

My family’s house in Beverly burned down years later. There was one great loss: three huge red leather scrapbooks kept by my grandfather about my father’s football career. Pictures (the original glossies) plus stories in all the papers, about a tough, fast halfback called “B” by his friends and Beebo in the sports sections, who played on a team that never lost a game.

I remembered one clip from the Boston Globe. Dated Monday, November 23, 1914, Coach Percy Haughton wrote about his Harvard team after they beat Yale: “From a photograph I have before me, it appears that Coolidge had not more than a three-yard start over two Yale men . . . . Bradlee is depicted a half yard behind [them], and yet in spite of this handicap, he succeeded in throwing first one Yale man, and then the other sufficiently off their stride to give Coolidge a clear field for the touchdown.” (Harvard coaches spoke and wrote the King’s English back then.) Coolidge was my father’s best friend, T. Jefferson Coolidge, who had recovered a Yale fumble on Harvard’s three-yard line, and ran it 97 yards for the score.

My father weighed less than 200 pounds, but he was tough, barrel-chested, strong, fast, and soft-spoken. Lying in his arms as a child and listening to that deep voice rolling around in his voice box was all the comfort and reassurance that a child could stand.

My mother was a little fancier. Josephine deGersdorff, from New York City, daughter of a prototypical Helen Hokinson garden club lady named Helen Suzette Crowninshield and a second-generation German lawyer named Carl August (pronounced OW-GUSTE) deGersdorff, who was a name partner in one of the swell law firms . . . Cravath, deGersdorff, Swaine & Wood. My mother was the co-holder of the high-jump record at Miss Chapin’s School for years, fluent in French and German, lovely to look at, well read, ambitious and flirtatious. She took singing lessons from a faded opera star.

She was called Jo, and when she sang “When I’m Calling You” during Assembly one morning at Dexter School in Brookline just outside of Boston—she forgot the words. I thought I’d die. Miss Fiske, the principal, whose motto was “Our best today; better tomorrow,” thanked her much too profusely, but I never really forgave her, even if I was only ten. Jo was ambitious, but mostly for us children . . . not so much socially (we were about as far up that ladder as anyone was going to go), but intellectually. We had governesses as long as we had the money to pay them, mostly desiccated women who used a switch to keep us speaking French. Every Saturday, no one in the family was allowed to speak anything but French. We took piano lessons (I can still play “Ole Man River” with the knuckles of my right hand). We took riding lessons at Vignole’s Riding Academy in Brookline. We were forced to go to the Boston Symphony’s Children’s Concerts (Ernest Schelling, conductor) on Saturday mornings. We were taken to the opera every spring, when the Met came to Boston. One day when I was twelve, I was taken to an afternoon performance of Madame Butterfly, followed after supper by four hours of Parsifal (starring Lauritz Melchior and Kirsten Flagstad). We hardly ever pretended to be sick and miss school, because that meant listening to Josephine practice her scales for two hours.

They made an odd couple, come to think of it. My father would get pretty well tanked when forced to host or even attend her musical evenings. My mother quickly learned to loathe afternoons burning brush in the Beverly woods. My father loved words, but talked only when he had a point to make or a story to tell. He had a great sense of humor and wit, but smiled more than he laughed. My mother talked a lot, especially when she was nervous. She really had no sense of humor, but she laughed a lot. Great teeth.

But figuratively or literally he had his hand on her behind for most of half a century. Our sense of family was very strong, especially after the Depression, when the maids departed and we replaced them. Their life together was generally joyous and supportive. So was ours.

“Ours” was my older brother and younger sister, Frederick Josiah Bradlee III and Constance. Freddy dropped the “k,” the “Josiah,” and the “III” as soon as he could—when he opened on Broadway as Montgomery Clift’s understudy in Dame Nature. Connie was born the belle of the ball, and without any real education learned the art of coping at an early age, settling into the system with grace and comfort.

We children ate early by ourselves in the dining room, except Sunday nights. We all remember only hamburgers for supper and prunes for dessert. For months I stacked the prunes on a ledge under the table rather than eat them. That worked fine, until the time came to put extra leaves in the table one night for company, when all the prunes fell to the floor, caked with dust. I remember the debate between my parents about whether I should be made to eat them, right then and there. The prunes were on the menu because my mother was preoccupied by our bowel movements. On Christmas mornings, for instance, we were forced to wait for the last child’s bowel movement before we could go upstairs and op...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword

- Chapter 1: Early Years

- Chapter 2: Harvard

- Chapter 3: Navy

- Chapter 4: New Hampshire

- Chapter 5: Washington Post: First Tour

- Chapter 6: Paris I—Press Attaché

- Chapter 7: Paris II—Newsweek

- Chapter 8: Newsweek, Washington

- Chapter 9: JFK

- Chapter 10: Newsweek Sale; JFK; Phil

- Chapter 11: Post-JFK

- Chapter 12: Washington Post, 1965–71

- Chapter 13: Pentagon Papers

- Chapter 14: Watergate

- Chapter 15: After Watergate

- Chapter 16: Washington Post, 1975–80

- Chapter 17: Janet Cooke

- Chapter 18: National Security: Public Vs. Private

- Chapter 19: Moving Out, Moving On

- Index

- Footnotes

- Back Cover

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access A Good Life by Ben Bradlee in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Journalist Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.