- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

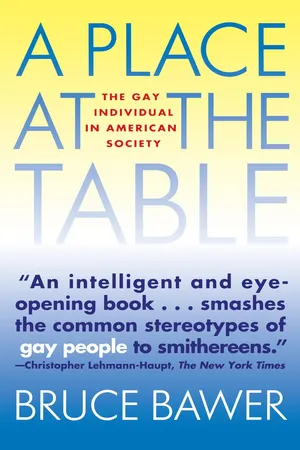

About this book

Bruce Bawer exposes the heated controversy over gay rights and presents a passionate plea for the recognition of common values, "a place at the table" for everyone.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Place at the Table by Bruce Bawer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & LGBT Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

“A sea

of

homosexuals”

One day a few years ago, when I was in my mid-twenties, I walked into a bookstore in midtown Manhattan. Though it has since been sold by one nationwide chain to another, the store is still there, one side of it facing Forty-second Street and the other opening into a cavernous stone passageway that in turn feeds into the main concourse of Grand Central Terminal. Near the store’s street entrance in those days was a large magazine section. A wall rack about ten feet wide displayed hundreds of periodicals, from Glamour to the Washington Monthly; at the rack’s base ran a foot-high counter containing tabloid-sized publications like the New York Review of Books and Screw, stacked in overlapping fashion so that only their titles showed.

Standing at this wall of magazines, when I entered the bookstore that day, was a tall boy of about fifteen. Lean and handsome, he looked, if anything, rather more shy and sweet-natured than the average New York City teenager; he radiated wholesomeness and sensitivity, and his neat dress and good posture suggested that he was well taken care of. This was, clearly, the much-loved son of a decent family.

To the average bookstore browser who glanced his way, he might have appeared to be an ordinary kid, spending an idle hour riffling aimlessly through Motor Trend and Sports Illustrated. But the moment I saw him, I knew this wasn’t the case. The boy was nervous—anxious, even— as he carefully returned a magazine to its place on the rack and glanced furtively to his left and right.

What was going on? Why was he so distressed? My eyes surveyed the hundreds of magazines, and suddenly—to my astonishment—I realized that I knew exactly what was happening.

I forgot immediately about the book I was after and instead walked over to the rack. Taking a magazine, I positioned myself half a step behind the boy and pretended to read. As I stood there unnoticed by him, he reached out, slipped a magazine from its holder, glanced at it absently, then neatly put it back. Again looking to his left and right, he took a couple of steps along the wall, pulled out another magazine, glanced at it in the same cursory way, and returned it to its proper place.

This went on for about five minutes. I had other things to do, but I couldn’t bring myself to leave. The boy was trying to work up his courage, and I wanted to see if he would.

He did. As I’d anticipated, all his shuttling back and forth brought him right back to where he’d begun. Standing there, he reached down to the foot-high counter, slipped out from under some other periodical a copy of a gay weekly called New York Native, and, trying to appear casual, opened it to the first inside page. If he’d barely glanced at the other magazines (in which, I knew, he’d only been feigning interest), he devoured this one. He stared at that first inside page in desperate bliss, gaped at it, ran his eyes down the columns of print as if he couldn’t really believe it existed, drinking in its prose in great huge gulps like a downed airman quaffing water after straggling across a desert. He finished that page and went on to the next, and the next, and the next. All the time the expression of sublime amazement never left his face— although every so often his eyes darted about fearfully to see if anyone was watching. It didn’t cross his mind, I’m sure, that he was being observed by me, directly behind him. Certainly it would never have occurred to him that I knew exactly what he was going through and was proud of him.

Proud? Yes. For when I looked at him, I felt as though I were seeing myself a few years earlier—confused, scared, reaching out tentatively for something that would explain to me who I was, and hoping no one would notice until I had something like an answer. In the same way that gay men can often recognize one another at a glance, so I’d known immediately not only that this boy was gay but also that he was just beginning to recognize his homosexuality, that he didn’t yet fully understand what that meant, and that there was nobody in his life—no parent, sibling, teacher, friend, or minister—to whom he felt he could turn. And so he’d brought his questions to this bookstore. I knew how difficult it had been for him to come here and to reach for that copy of the Native; I was proud of him for having worked up the courage.

As I stood there behind him, I looked over his shoulder at the pages of the Native. I don’t remember the specific contents: there were, I suppose, the usual articles about AIDS research, gay bashings, and recent gay-rights advances and setbacks, as well as the weekly statistical roundup of reported AIDS cases and deaths. But what leapt out at me, and stayed in my mind for some time afterward, were other things: a photograph, probably accompanying a review of some cabaret act, of a man in drag; photographs of black-clad men in bondage, presumably in advertisements for leather bars and S&M equipment; and photographs of hunky, bare-chested young men, no doubt promoting “massages” and “escort services” and X-rated videotapes.

These pictures irked me. The narrow, sex-obsessed image of gay life that they presented bore little resemblance to my life or to the lives of my gay friends—or, for that matter, to the lives of the vast majority of gay Americans. Yet this was the image proffered by the Native and other such magazines. For most of the editors and regular readers of these magazines were not simply gay; they were people whose lives revolved around—and who saw virtually everything else in their lives as relating directly to—their sexual orientation. The image of gay life promulgated in these publications did not reflect actual gay life in America; rather, they presented a picture of gay identity as defined by a small but highly visible minority of the gay population. There was, objectively, nothing wrong with this; these people had their own tastes and interests, their own way of viewing the world and themselves. Fine; that was their right. What was wrong was that the image that they projected had, for decades, strongly influenced the general public’s ideas about homosexuality. Thanks to their extraordinary visibility—and to the fact that gay men like me, who might serve as alternative role models for such a boy, kept their homosexuality largely to themselves—many heterosexuals tended to equate homosexuality with the most irresponsible and sex-obsessed elements of the gay population. That image had provided ammunition to gay-bashers, had helped to bolster the widely held view of gays as a mysteriously threatening Other, and had exacerbated the confusion of generations of young men who, attempting to come to terms with their homosexuality, had stared bemusedly at the pictures in magazines like the Native and said to themselves: “But this isn’t me.”

As I looked at those photographs over the boy’s shoulder, then, my pride became mixed with concern. It disturbed me to think that those pictures should shape his notion of what it meant to be gay. I wished I could tap him on the shoulder and introduce myself and say—well, something more or less like this:

“Don’t think those pictures of leathermen and cross-dressers and nipple clamps are what gay life is all about. They’re not—no more than a Penthouse centerfold is what straight life is all about. There are hundreds of thousands of homosexuals in New York, and only twenty thousand subscribe to the Native: far more of us read Time or Newsweek than read the Native or anything like it. Gays are liberal and conservative, attractive and homely, smart and stupid. Some wear earrings and some wear three-piece suits. Some you couldn’t imagine having anything in common with—and some are very, very much like you.

“So don’t let this magazine disturb you. Don’t let it add to your confusion about your sexuality. Don’t let it make you think, Well, if that’s what it means to be gay, then I guess I must not be gay. Don’t let it make you think, Well, I’m gay, so I guess I’d better try to become like that. And don’t let it make you think, Well, I’m gay, but I refuse to become like that, so I guess the only alternative is to repress it and marry.

“Wrong, wrong, wrong. Being gay doesn’t oblige you to be anything— except yourself. Don’t let anyone, straight or gay, tell you who you are. You’re you. You’re the boy you’ve always been, the boy you see when you look in the mirror. Yes, you’ve always felt there was something different about you, something you couldn’t quite put a name to, and in the past few months or years you’ve come to understand and to struggle with the truth about that difference. You’re beginning to realize that the rest of your life is not going to play out quite the way you or your parents have envisioned it. You didn’t want to accept this at first, but now you know you have no alternative. And you want to be honest with yourself and your parents about this; more than anything else, you want to talk to them about this momentous truth you’re discovering about yourself. But you can’t bring yourself to do so, since you’re pretty sure they’d be angry. You resent them for this. And on top of that you despise yourself, because even though you’ve always talked to them about everything, you’re hiding from them a very important part of who you are, and because—even though you didn’t choose to be gay (who, after all, would choose to experience the fear and loneliness and be wilderment you’ve known?)—you feel as if you’ve done something awful to them by being this way.

“Well, don’t feel guilty. Don’t hate yourself. And don’t hate your parents. When you tell them about your homosexuality, give them time to understand, the same way you’ve had to give yourself time to understand. As you know, it’s not easy to understand. And above all, be true to yourself, your good and decent self, and understand that there’s no inherent conflict between homosexuality and decency. Don’t let anyone, straight or gay, tell you any different.”

I wanted to say all this to the boy—all this and much more. Of course, it was a foolish thought: the boy needed to be listened to more than lectured. Besides, it was hardly as if I had my own act together: not that many years had passed since I’d accepted that I was gay. I’d still never had a steady relationship, or discussed my homosexuality with some of my friends or with the editors of the monthly review The New Criterion, for which I wrote regularly. I’d never been rejected by a friend or relative for being gay, and hadn’t yet suffered a professional setback on account of it. I was still figuring out how my homosexuality fit into my life, still trying to figure out how to deal with it on a daily basis. I considered it wrong to lie; I also considered it inappropriate to discuss it under, well, inappropriate circumstances. But which circumstances were appropriate? The more I thought about it, the blurrier the line seemed to be between what some homosexuals (and my own conscience) would consider dishonest concealment and what some heterosexuals might consider flaunting my sexuality.

I’d made one rule for myself: if someone asked me point-blank “Are you gay?” I would answer honestly. But that was a relatively easy rule, and didn’t begin to speak to the variety of situations that cropped up. Part of the problem, I realized, was that most heterosexuals are constantly alluding to their personal relationships without even realizing it, let alone considering it inappropriate; they only notice it, and consider it inappropriate, when a homosexual does the same thing. Married people have pictures of their spouses on their office desks; they wear wedding rings to work; in conversation with clients and co-workers, they mention their wives or husbands without giving it a thought. Assuming a gay co-worker to be straight, they make friendly jokes about “you single people” and suggest teasingly that he or she is romantically interested in this or that member of the opposite sex.

Can a heterosexual reader understand how this feels? Imagine, if you’re a straight male, working in an office where everyone else is gay. They all have pictures of their lovers on their desks, but you don’t feel free to display a picture of your wife. Their lovers drop by at the end of the day and kiss them and drive them home, but you can’t let your wife come to the office, because it might create discomfort and ill will, if not endanger your job. Your co-workers chat openly with their lovers on the phone, calling them “honey” and saying “I love you!” before hanging up; when you phone your wife you assume an affable but not intimate tone, as if she were just a casual friend. Occasionally your employer holds a party to which all employees’ lovers are invited, but your spouse is not invited and stays home. At the party your co-workers and their lovers chat about their home life and you listen quietly, trying to smile when one of them tells you congenially: “Hey, we’ll have to find you a boyfriend one of these days!” For it doesn’t even occur to them that you might have a wife at home—they assume you’re gay, same as them. After all, they like you; you get along; of course you’re gay. You want to correct their impression, but you can’t quite bring yourself to do so: your heterosexuality might be all right with them, but it might not. Being honest with them about your heterosexuality would doubtless force some of them to rethink their prejudices about heterosexuals and help them to see heterosexuals as human beings just like themselves. But at the same time your disclosure would almost certainly cause a change in the tone that some of them take with you; at the very least, there’d be a noticeable awkwardness, a stilted quality, a hint of condescension in their relations with you, as if you’d suddenly turned into another person. You know this because it’s happened before, with other people in other offices.

Try to imagine how you would feel in this position, and you’ll begin, perhaps, to understand what most gay people go through. How does one deal with such circumstances? The most radical elements of the gay population have their answer: hurl your sexuality in their faces, mention it constantly, return rancor for rancor. At the opposite end of the spectrum, completely closeted gays have another answer: don’t rock the boat, turn the other cheek, lie. Neither approach satisfied me. The right answer, it seemed, lay somewhere between these two poles. But where? The more I lived as a self-acknowledged gay man in a straight world, the more I sensed that there was no perfect middle, that there were no cut-and-dried answers, that every situation was somewhat different from the next, and that for a gay person each human encounter posed a new moral and social challenge.

Perhaps, in retrospect, what I had to offer the boy in the bookstore was not my certainties but my confusion. How helpful it might have been to him—and, yes, to me—to talk about the challenges we both faced! But naturally this was impossible. A tap on the shoulder, a man’s voice saying, “Excuse me”—it would have scared the hell out of him. He probably would have thought I was making a pass and raced out of there, his heart pounding. And what an accomplishment that would’ve been. I’d have succeeded only in reinforcing for him the most offensive myth of all about gay life: that every gay man is a would-be molester, on the prowl for teenage boys to “recruit.”

What did I do, then? Nothing. I stood there silently as the boy finished reading the Native. I watched him slip it neatly back into its place on the counter. I watched him leave.

As he stepped out into the dark interior of Grand Central Terminal, I wondered when he would come out to his family and friends. In a week? A year? Twenty years? Never? I hoped that he would take care of himself, and that his parents, if and when he did come out to them, would be kind. And I wished that somewhere in the store there had been a book for me to press into his hands, a book that would have helped him to understand and accept himself—and that might even have helped his loved ones to understand and accept, too.

This book is for that boy.

It’s also for the homemaker and mother who phoned the Donahue show during a discussion of gay issues to say in a sympathetic voice that she didn’t know or understand much about homosexuality, and was in fact confused about it, but wanted to learn about it.

It’s for all the heterosexuals who have complained at some time or another that they’re “sick and tired of these gays pushing their sex lives in our faces.”

It’s for the woman who stood up at a 1992 meeting of the anti-gay Oregon Citizens Alliance and wept about the “spread” of homosexuality in America. To quote Robert E. Sullivan Jr.’s report in The New Republic: “‘I think of the kids, and in twenty years from now, how it will all be,’ she says, her eyes welling up. ‘And I just. I just …’ The woman can’t go on.”

It’s for the audience member who said on the Jackie Mason show that “teaching that homosexuality is normal … you twist a child’s mind.”

It’s for the straight woman who, on a TV news report about gays in the military, was seen confronting Margarethe Cammermeyer, a former army colonel and Vietnam vet who had been dismissed for being a lesbian. Her voice quavering, the straight woman shrieked that gays and lesbians posed a threat to her family and to America, a country for which she would gladly give her life. Cammermeyer turned to her and replied in a polite, calm voice, “I almost did give my life for it.” In sincere terror, the woman barked back, “I wish you had!” and stalked away.

It’s for a friend of mine, a gay conservative writer, who, when I ranted over dinner about the anti-gay rhetoric at the 1992 Republican convention, said quietly, “It’s best not to talk about these things.”

It’s for the kind, soft-spoken member of the radical direct-action group Queer Nation who said to me over another dinner, “I wish I could burn down every church in America.”

It’s for Bill Clinton, whose support for gay rights as a presidential candidate inspired countless American homosexuals, and whose backing away from that support in the months after his inauguration strongly disheartened them. Three days before becoming president, Clinton said, “Let us build an American home for the twenty-first century where everyone has a place at the table and not a single child is left behind.” The vision lives, even if Clinton’s dedication to it has seemed to waver.

It’s for the children of people like Dan Quayle and Pat Buchanan. For those children’s sake, I hope they’re not gay: homosexuality is not an easy row to hoe, especially when you’ve got parents like Quayle and Buchanan. For the country’s sake, I sometimes wish those kids were gay: it might help their fathers to understand how needless are the divisions they promote, how false the myths they perpetuate, and how unwittingly cruel their casual condemnations.

For the present divisions are needless. Especially at a time when the nation and the world face crucial problems, arguing about homosexuality and gay rights is a waste of time, energy, money, and emotion. To many heterosexuals, such as that bemused Donahue caller, homosexuality is a new and peculiar issue. But homosexuals have always been here. The chief difference is that in earlier times homosexuals led more or less secretive personal lives. Many were married and satisfied their sexual longings on the sly, with strangers. Often driven to severe neurosis by society’s opprobrium, they lived in terror of arrest, exposure, disgrace. Today homosexuals are increasingly honest with themselves and others about their sexual orientation. As a consequence of this openness, heterosexuals are gradually becoming aware of the large numbers of homosexuals living among them. For many heterosexuals, especially those who have been touched closely by it—who have learned, in other words, that a friend or relative is gay—this openness has resulted in increased understanding and tolerance. For others, who may have experienced this openness only at a distance—that is, by seeing TV news stories about gay protesters or AIDS patients—it has been a cause of discomfort and confusion.

This discomfort and confusion have been exploited by certain reactionaries, notably leaders of the so-called religious right, who have spread lies about what homosexuality is and about what the gay-rights movement seeks to achieve. What it seeks, quite simply, is to abolish the inequities that homosexuals have to live with and that make it difficult and dangerous for them to live honestly. The point that has been lost amid all the rhetoric is that whatever anti-gay reactionaries may do, whatever laws they manage to enact or block or repeal, they cannot keep a single gay person from being gay; they can only keep him from being honest about it. And that dishonesty is not in anyone’s interest, no matter what they may think. Dishonesty about homosexuality only breeds ignorance—and as a result of that ignorance, hate is sown in places where there might be love, distrust where there might be understanding, antagonism and violence where there might be harmony and peace. It is, indeed, dishonesty—both on the part of professional bigots who deliberately misrepresent homosexuality and on the part of the majority of gays who, feeling compelled by the ubiquity of prejudice to hide their homosexuality, have rendered themselves powerless to challenge those false representations—that has kept most Americans confused and ill-informed about the basic truths of homosexuality and gay life.

I wrote this book because I am the last homosexual who I ever thought would write a book about homosexuality. I’m a poet, usually classified as an elitist practitioner of “New Formalism,” and a literary critic, generally lumped together with certain neoconservative intellectuals. I’m a monogamous, churchgoing Christian. I wrote this book, in short, be cause I am a member of what must be called—much as I hate to borrow a phrase from our thirty-seventh President—the “silent majority” of homosexuals. One of the things that characterize us silent gays is that, unlike the more visible minority of gays, we tend not to consider ourselves “members” of anything. Some of us are thoroughly closeted; others, though fully open about our homosexuality, simply don’t think of it as defining us, as explaining everything about us. Yet as the debate over homosexuality has escalated, some of us have grown increasingly impatient—impatient with the lies that are being told about us by antigay crusaders; impatient with the way in which TV news shows routinely illustrate gay-rights stories by showing videotape of leathermen and drag queens at Gay Pride Day marches; and impatient with the way in which many self-appointed spokespeople for the gay population talk about the subject. (These “professional gays” often describe homosexuality in such a way that I, for ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Contents

- Author’s note

- 1 “A sea of homosexuals”

- 2 “Don’t you think homosexuality is wrong?”

- 3 “Everything I do is gay”

- 4 “The only valid foundation”