- 832 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Drawing on newly discovered sources and writing with brilliance, drama, and profound historical insight, Hugh Thomas presents an engrossing narrative of one of the most significant events of Western history. Ringing with the fury of two great empires locked in an epic battle, Conquest captures in extraordinary detail the Mexican and Spanish civilizations and offers unprecedented in-depth portraits of the legendary opponents, Montezuma and Cortés. Conquest is an essential work of history from one of our most gifted historians.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Conquest by Hugh Thomas in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & European History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

I

Ancient Mexico

1

Harmony and order

“The fashion of living [in Mexico] is almost the same as in Spain with just as much harmony and order . . .”

Hernán Cortés to Charles V, 1521

THE BEAUTIFUL POSITION of the Mexican capital, Tenochtitlan, could scarcely have been improved upon. The city stood over seven thousand feet up, on an island near the shore of a great lake. It was two hundred miles from the sea to the west, a hundred and fifty to the east. The lake lay in the centre of a broad valley surrounded by magnificent mountains, two of which were volcanoes. One of these was always covered by snow: “O Mexico, that such mountains should encircle and crown thee,” a Spanish Franciscan would exult a few years later.1 The sun shone brilliantly most days, the air was clear, the sky was as blue as the water of the lake, the colours were intense, the nights cold.

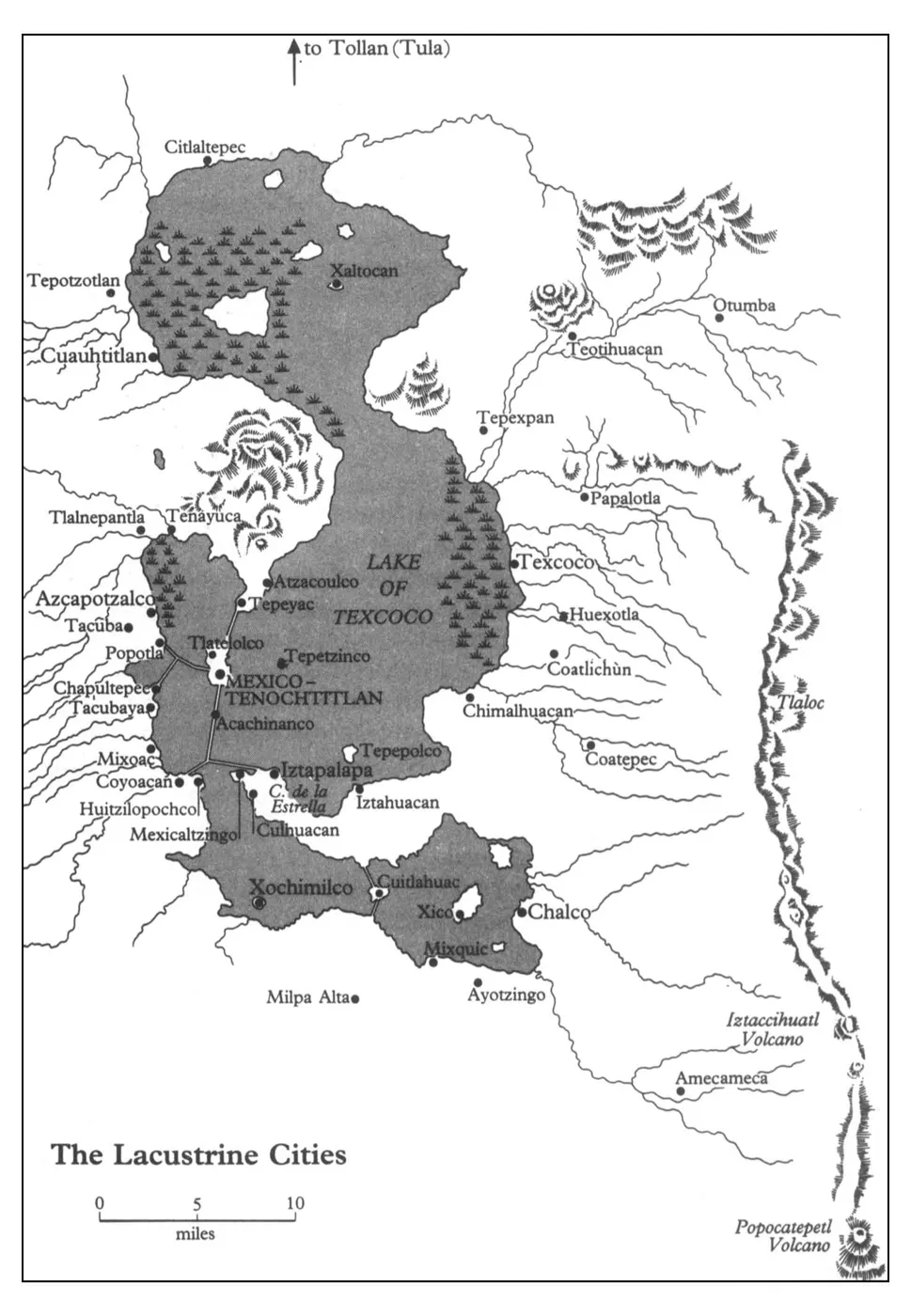

Like Venice, with which it would be insistently compared, Tenochtitlan had been built over several generations.2 The tiny natural island at the centre of it had been extended to cover 2,500 acres by driving in stakes, and throwing mud and rocks into the gaps. Tenochtitlan boasted about thirty fine high palaces made of a reddish, porous volcanic stone.3 The smaller, single-storey houses, in which most of the 250,000 or so inhabitants lived, were of adobe and usually painted white.4 Many of these had been secured against floods by being raised on platforms. The lake was alive with canoes of different sizes bringing tribute and commercial goods. The shores were dotted with well-constructed small towns which owed allegiance to the great city on the water.

The centre of Tenochtitlan was a walled holy precinct, with numerous sacred buildings, including several pyramids with temples on top.5 Streets and canals led away straight from the precinct at all four points of the compass. Nearby stood the Emperor’s palace. There were many minor pyramids in the city, each the base for temples to different gods: the pyramids themselves, characteristic religious edifices of the region, being a human tribute to the splendour of the surrounding volcanoes.

Tenochtitlan’s site made it seem impregnable. The city had never been attacked. The Mexica had only to raise the bridges on the three causeways which connected their capital to the mainland to be beyond the reach of any plausible enemy. A poem demanded:

Who could conquer Tenochtitlan?

Who could shake the foundation of heaven . . . ?6

Tenochtitlan’s safety had been underpinned for ninety years by an alliance with two other cities on, respectively, the west and east sides of the lake – Tacuba and Texcoco. Both were satellites of Tenochtitlan, though Texcoco, the capital of culture, was formidable in its own right: an elegant version of the language of the valley, Nahuatl, was spoken there. Tacuba was tiny, for it may have had only 120 houses.7 These two places obeyed the Emperor of the Mexica in respect of military affairs. Otherwise they were independent. The royal houses, as there is no reason not to call them, of both were linked by blood with that of Tenochtitlan.8

These allies helped to guarantee a mutually advantageous lacustrine economy of fifty or so small, self-governing city states, many of them within sight of one another, none of them self-sufficient. Wood was available for fire (as for carved furniture, agricultural tools, canoes, weapons, and idols) from the slopes of the mountains; flint and obsidian could be obtained for some instruments from a zone in the north-east; there was clay for pottery and figurines (a flourishing art, with at least nine different wares) while, from the shore of the lake, came salt, and reeds for baskets.

The emperors of Mexico dominated not only the Valley of Mexico.9 Beyond the volcanoes, they had, during the previous three generations, established their authority to the east as far as the Gulf of Mexico. Their sway extended far down the coast of the Pacific Ocean in the west to Xoconocho, the best source of the much-prized green feathers of the quetzal bird. To the south, they had led armies to remote conquests in rain forests a month’s march away. Tenochtitlan thus controlled three distinct zones: the tropics, near the oceans; a temperate area, beyond the volcanoes; and the mountainous region, nearby. Hence the variety of products for sale in the imperial capital.

The heartland of the empire, the Valley of Mexico, was seventy-five miles north to south, forty east to west: about three thousand square miles; but the empire itself covered 125,000 square miles.10

Tenochtitlan should have been self-confident. There was no city bigger, more powerful, or richer within the world of which the people of the valley were informed. It acted as the focus for thousands of immigrants, of whom some had come because of the demand for their crafts: lapidaries, for example, from Xochimilco. A single family had ruled the city for over a century. A “mosaic” of altogether nearly four hundred cities, each with its own ruler, sent regular deliveries to the Emperor of (to mention the most important items) maize (the local staff of life) and beans, cotton cloaks and other clothes, as well as several types of war costumes (war tunics, often feathered, were sent from all but eight out of thirty-eight provinces).11 Tribute included raw materials and goods in an unfinished state (beaten but not embellished gold), as well as manufactured items (including amber and crystal lip plugs, and strings of jade or turquoise beads).

*

The power of the Mexica in the year 1518 or, as they called it, 13-Slate, seemed to rest upon solid foundations. Exchange of goods was well established. Cocoa beans and cloaks, sometimes canoes, copper axes, and feather quills full of gold dust, were used as currency (a small cloak was reckoned as worth between sixty-five and a hundred cocoa beans).12 But payments for services were usually made in kind.

There were markets in all districts: one of these, that in the city of Tlatelolco, by now a large suburb of Tenochtitlan, was the biggest market in the Americas, an emporium for the entire region. Even goods from distant Guatemala were exchanged there. Meantime, trade on a small scale in old Mexico was carried on by nearly everyone, for marketing the household’s product was the main activity of family life.

The Mexican empire had the benefit of a remarkable lingua franca. This was Nahuatl: in the words of one who knew it, a “smooth and malleable language, both majestic and of great quality, comprehensive, and easily mastered”.13 It lent itself to expressive metaphors, and eloquent repetitions. It inspired oratory and poetry, recited both as a pastime and to celebrate the gods.14 An equally interesting manifestation was the tradition of long speeches, huehuetlatolli, “words of the old men”, learned by heart (as was the poetry) for public occasions, and covering a vast number of themes, usually affording the advice that temperance was best.

Nahuatl was an oral language. But the Mexica, like the other peoples in the valley, used pictographs and ideograms for writing. Names of persons – for example, Acamapichtli (“handful of reeds”) or Miahuaxochitl (“turquoise maize flower”) could always be represented by the former. Perhaps the Mexica were moving towards something like the syllabic script of the Maya. Even a development on that scale would not have been able to express the subtleties of their speech. Yet Nahuatl was, as the Castilian philologist, Antonio de Nebrija had, in the 1490s, described Castilian, “a language of empire”. Appropriately, the literal translation of the word for a ruler, tlatoani, was “spokesman”: he who speaks or, perhaps, he who commands (huey tlatoani, emperor, was “high spokesman”). Mexican writers could also express elegiac melancholy in a way which seems almost to echo French poetry of the same era:

I am to pass away like a faded flower

My fame will be nothing, my renown on earth will vanish.15

Nahuatl, its foremost modern scholar has passionately said, “is a language which should never die”.16

Beautiful painted books (usually called codices) recorded the possession of land, as of history, with family trees and maps supporting the inclination of the ancient Mexicans to be litigious. The importance of this side of life can be gathered from the 480,000 sheets of bark paper regularly sent as tribute to “the storehouses of the ruler of Tenochtitlan”.17

*

The politics of the empire were happily guaranteed by the arrangements for imperial succession. Though normal inheritance customarily passed from father to son, a new emperor, always of the same family as his predecessor, was usually his brother, or cousin, who had performed well in a recent war. Thus the Emperor in 1518, Montezuma II, was the eighth son of Axayácatl, an emperor who died in 1481.18 Montezuma had followed an uncle, Ahuítzotl, who had died in 1502. In the selection of a new ruler, about thirty lords, together with the kings of Texcoco and Tacuba, acted as an electoral college.19 No succession so decided seems to have been challenged, even if sometimes there had been rival candidates.20 (Vestiges of this method of election can be detected by the imaginative in modern methods of selecting the President of Mexico.)21 Disputes were avoided since each election of a ruler was accompanied by the nomination of four other leaders, who in theory would remain in their places throughout the reign of an emperor, and of whom one would become the heir.22 No doubt the actual duties of these officials (“Killer of Men”, “Keeper of the House of Darkness”) had become detached from the titles just as the “Chief Butler of the King” had ceased in Castile to have much to do with the provision of wine. The system of succession varied in nearby cities: in most of them, the ruler was hereditary in the family of the monarch, though in some places the kingship did not always fall to the eldest son. In Texcoco primogeniture was the rule.23

It is true that the deaths of the last three emperors had seemed a little odd: Ahuítzotl died from a blow on the head when fleeing from flood waters; Tizoc was rumoured to have been killed by witches; and Axayácatl died after defeat in battle. Yet there is nothing to prove that in fact they did not die from natural causes.24

The Mexican emperor stood for, and concerned himself with, the external face of the empire. Internal affairs were ultimately directed by a deputy emperor, a cousin, the cihuacoatl, a title which he shared with that of a great goddess, and whose literal translation, “woman snake”, connected him with the feminine side of divinity. The word gives an inadequate picture of his multifarious duties. Probably in the beginning this official was the priest of the goddess whose name he had.

The internal life of Tenochtitlan was stable. It was in practice managed by an interlocking network of something between a clan, a guild and a district, known as the calpulli, a word about whose precise nature every generation of scholars has a new theory, only agreeing that it indicated a self-governing unit, and that it held land which its members did not own, but used. It was probably an association of linked extended families. In several calpultin (that being the plural style) families had the same professions. Thus featherworkers mostly lived in Amantlan, a district which may once have been an independent village.

Each calpulli had its own gods, priests, and traditions. Marriage (celebrated in old Mexico with as much ceremonial as in Europe) outside the calpulli, though not impossible, was unusual. The calpulli was the body which mobilised the Mexica for war, for cleaning streets, and for attending festivals. Farmers of land which had been granted by the calpulli gave a proportion of the crops (perhaps a third) to that body for delivery to the imperial administration. Through the calpulli, the farmer heard the requests, or the orders, of the Emperor.25 There were perhaps as many as eighty of these in Tenochtitlan. Earlier, the leader, the calpullec, had apparently been elected but, by the fifteenth century, that office had become hereditary and lifelong. He too had a council of elders to consult, just as the Emperor had his more formally contrived advisers.

The most powerful calpulli was that in the suburb known as Cueopan, where there lived the so-called long-distance merchants, the pochteca. These had a bad name among Mexica: they seemed to be “the greedy, the well-fed, the covetous, the niggardly . . . who coveted wealth”. But they were officially praised: “men who, leading the caravan...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Dedication

- List of Illustrations

- Preface

- Notes

- Part I: Ancient Mexico

- Part II: Spain of the Golden Age

- Part III: To know the Secrets of the Land

- Part IV: Cortés and Montezuma

- Part V: Cortés’ Plans Undone

- Part VI: The Spanish Recovery

- Part VII: The Battle for Tenochtitlan

- Part VIII: Aftermath

- Epilogue

- Illustrations

- Glossary

- Appendices

- Genealogies

- Unpublished Documents

- Chapter Notes

- Sources

- Index

- Copyright