eBook - ePub

One River

About this book

The story of two generations of scientific explorers in South America—Richard Evans Schultes and his protégé Wade Davis—an epic tale of adventure and a compelling work of natural history.

In 1941, Professor Richard Evan Schultes took a leave from Harvard and disappeared into the Amazon, where he spent the next twelve years mapping uncharted rivers and living among dozens of Indian tribes. In the 1970s, he sent two prize students, Tim Plowman and Wade Davis, to follow in his footsteps and unveil the botanical secrets of coca, the notorious source of cocaine, a sacred plant known to the Inca as the Divine Leaf of Immortality.

A stunning account of adventure and discovery, betrayal and destruction, One River is a story of two generations of explorers drawn together by the transcendent knowledge of Indian peoples, the visionary realms of the shaman, and the extraordinary plants that sustain all life in a forest that once stood immense and inviolable.

In 1941, Professor Richard Evan Schultes took a leave from Harvard and disappeared into the Amazon, where he spent the next twelve years mapping uncharted rivers and living among dozens of Indian tribes. In the 1970s, he sent two prize students, Tim Plowman and Wade Davis, to follow in his footsteps and unveil the botanical secrets of coca, the notorious source of cocaine, a sacred plant known to the Inca as the Divine Leaf of Immortality.

A stunning account of adventure and discovery, betrayal and destruction, One River is a story of two generations of explorers drawn together by the transcendent knowledge of Indian peoples, the visionary realms of the shaman, and the extraordinary plants that sustain all life in a forest that once stood immense and inviolable.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER ONE Juan’s Farewell

WHEN I FIRST lived in Colombia, I used to stay from time to time on a farm just outside the city of Medellín. The land was owned by a campesino, Juan Evangelista Rojas, who was rich beyond his wildest imaginings, though he didn’t know it. Juan and his twin sister, Rosa, neither of whom ever married, had lived on the farm most of their lives, and during that time—sixty or seventy years, no one really knew—the city had spread north following the new highway to Bogotá, and the barrios now lapped at the base of their land. Their property was worth millions of pesos, but for reasons of their own, both Rosa and Juan continued to work as they always had, she by gathering herbs and coaxing the odd egg from a flock of sad-looking chickens, he by making charcoal, which he sold by the bagful to the passing peasants on the Guarne road. I don’t think either Juan or Rosa ever thought of selling off any land. They would never have been able to agree on which section to let go, and besides, from the main house at the edge of a pine forest at the top of the farm, it was easy to ignore the encroaching city.

The land ran in a narrow swath up and down a precipitous quebrada, and the gradient was so steep that the new highway, though but a mile away, lay more than two thousand feet below. Juan was forever scampering up and down the hillside gathering firewood or tending an astonishing variety of crops: potatoes and onions in the mist by the pine woods, coffee a thousand feet below near the waterfall, where the eagle had turned into a dove, and bananas, plantains, and cacao at the very bottom, where the hot tropical sun blistered the pavement of the highway. Juan’s imagination breathed life and mystery into every rock and tree. Angels often appeared to him, and he claimed that the crosses set up to mark the route of his mother’s funeral sometimes glowed red in the daytime and green by night. At one bend in the main trail, where the pallbearers had tripped and the corpse had tumbled out of the casket crushing the giant horsetails, he never failed to pause to say a prayer or at least to cross himself. Sometimes he brought manure to the spot to fertilize the ground so that the delicate plants need never again feel the weight of death.

There was a beautiful order to Juan’s world. Everything had its place, and the land, though large enough to embrace all his dreams, was of a human scale. One could know all of it intimately. In a wild and ragged country the farm was safe. Sometimes late in the afternoon when the work was done, Juan and I would walk up the road to a nearby estadero and drink together on the verandah overlooking his fields. Fueled by a few glasses of aguardiente Juan would speak of the world beyond the farm, of the seasons in his youth when he, like everyone in rural Colombia, had to move to stay alive. He told of logging on the Río Magdalena when there were still forests to be cut, and of men eaten by black caiman in the swamps of the Chocó. The most horrific tales were of La Violencia, the civil war between liberals and conservatives, that racked the nation in the forties and early fifties, a time when entire villages were ravaged and populations destroyed. Juan had fought for the liberals, or at least had managed to be shot by the conservatives, who left him to die in a pile of dead children in the plaza of a small town in Cauca. Since then, he claimed, whenever he thought too much he felt pain. So he tried not to think, only to look and see.

Because of his own itinerant past Juan had no difficulty understanding what I was doing in Colombia. “Buscando trabajo,” he would explain to his incredulous neighbors. “The gringo is looking for work.” In fact, just twenty at the time, I was in South America to study plants. A letter of introduction from my professor, Richard Evans Schultes, then director of the Botanical Museum at Harvard, had secured me a room at the Jardín Botánico Joaquin Antonio Uribe in Medellín. But I was never quite comfortable there. The garden, located in the north of the city, is a lavish complex of neocolonial buildings sequestered from the surrounding barrio by enormous white stucco walls crowned with barbed wire and shards of glass. Beyond the walls run acres of more modest structures of cinder block and mud, zinc roofs draped in wires which light the lamps of the hundreds of brothels that surround the garden. Inside the walls is the illusion of paradise, but the land used to belong to the poor, and according to Juan, the tranquil ponds with their lilies and papyrus once ran red with the blood of victims of La Violencia.

So while I kept my room at the garden, I preferred to live with Juan, and it was from the farm that most of my initial botanical forays originated. In the beginning these wanderings had a random quality. Colombia, with three great branches of the Andes fanning out northward toward the wide Caribbean coastal plain, the rich valleys of the Cauca and Magdalena, the sweeping grasslands of the eastern llanos and the endless forests of the Chocó and Amazonas, is ecologically and geographically the most diverse nation on earth. A naturalist need only spin the compass to discover plants and even animals unknown to science. In the past months I had gone away on several occasions to the rain forests of northern Antioquia, across the Gulf of Urabá to Acandi and the Darien, and south into the mountains of Huila. At the farm Juan became used to my comings and goings, and he always anticipated my return with some excitement. It was as if I had become his eyes and ears onto a world of his own past, a life of uncertainty and adventure, of magic and discovery.

As for life on the farm, it went along in its own casual way. It was an innocent period in Medellín, the spring of 1974. The Cartel was emerging, though no one knew quite how, and no one realized how sordid and murderous it would become. Most Americans had never heard of cocaine. For those who had, it was a sweet sister, incapable of harm. Just beyond the pine forest passed a country lane that led in a few hours to Río Negro and the farm where Carlos Ledher would eventually build his empire, complete with the bizarre statue of John Lennon, stuck like a hood ornament onto a hillside of the hacienda. No one could have imagined how rich he would become or that he would end up in a Miami jail, locked away for life. The cocaine trade, such as it was, still lay in the hands of the independent drifter, people like our neighbor Nancy, an elusive California surfer who lived alone and dazzled the locals with her beauty and the rainbows she painted each morning across her eyelids. Sometimes on Sundays, just as Juan and I were settling down to a day in the garden, musicians would appear with briefcases full of cocaine and simple requests to play their guitars into the night. Almost always Juan welcomed them and then slipped away into the forest that led to the waterfall, a place of tree ferns and mist, where plants dictated the mood and he felt free.

Juan had a brother, Roberto, who was a carpenter, the only one I ever knew who took wind into account before driving a nail. Roberto was explaining this to me one afternoon when Juan came by with the telegram I had been expecting. He found us hammering on the roof of the new pigsty. The telegram came from Tim Plowman, one of Professor Schultes’s recent graduate students. For the past month Tim had been languishing in Barranquilla, a miserably hot and dismal industrial city on the north coast, haggling with customs officials who, by some curious sleight of hand, had determined that the pickup truck that he had shipped south from Miami was, in fact, theirs. Evidently, Tim had finally persuaded them otherwise and was at last ready to begin his botanical explorations. I was to meet him in three days at the Residencia Medellín in Santa Marta, a sun-bleached port on the Caribbean coast sixty miles east of Barranquilla.

Juan seized the opportunity like lightning. To get to the coast I would have to pass through a village he knew on the Río Magdalena where I could buy or capture an ocelot that he would train as the nucleus of a circus. It was an old idea of his. There hadn’t been an ocelot in that part of the Magdalena Valley in forty years. Juan surely knew this, yet he clung to his dream like a limpet. Like all campesinos Juan had dozens of plans for getting rich, impossibly complicated schemes that had nothing whatsoever to do with the day-to-day reality of his life.

As I made ready for the coast, Juan prepared for my departure. For a Colombian there is no such thing as a casual leave-taking, and for Juan it was inconceivable that I might depart without a long afternoon at the estadero. Each of his brothers and sisters—and one would discover at such moments with stunning clarity just how many there were—would wax eloquent about the prospects of the journey, its promise and hazards, with each prognosis followed en seguida by a stiff shot of trago that brought the soft hues of sunset alive at midday. The afternoon grew charged with threatening earthquakes, impossible rapids, train wrecks, sorcery, volcanoes, floods of rain, horrendous unknown diseases, and sly deceitful soldiers with the demeanor of feral dogs. Thieves lurked at every crossroads except on the north coast. There everyone was a thief.

“Life is an empty glass,” Juan would say. “It’s up to you how fast you fill it” Inevitably, Rosa would then begin to cry. That was the signal. One had to get out fast or make new plans for the night. This time, against all odds, I managed to get myself and Juan out of the estadero and onto the flota that bounced and rumbled down the dirt road to the city, leaving Rosa and a pair of sisters red-eyed and wailing in the dust.

In Colombia there are no train schedules, only rumors. The guide books maintain that there is no train service out of Medellín to the Caribbean coast. I was quite sure there was and did my best to get to the train station at an hour that made sense to Juan. His estimate left just enough time to swing by the Botanical Garden, pick up my mail and some extra equipment, and battle the traffic and crowds of the city. As we parted at the station, I promised Juan somewhat disingenuously that I would do my best to find his ocelot. I told him I expected to be back in a week or two. He was delighted and mentioned something about building a cage. I said it would be a good idea. Neither of us could have known that I would be away for many months and that this passage to the coast would be the first leg of an intermittent journey that would last eight years, taking me to some of the most remote and inaccessible reaches of the continent.

The train ran north past the sprawling outskirts of Medellín and into the rich farmland of Antioquia. In the fading light and through a cracked window coated in dust and fingerprints, I could just make out the flank of Juan’s farm above Copacabana, and beyond, the mountains of the Cordillera Central looming jet black on the horizon. Inside the train the passengers—among them a dozen military conscripts, campesinos who still smelled of earth and smoke—settled in for the thirty-hour trip to the coast. Lulled by the rhythmic clacking of the wheels and the steady pounding of rain on the metal roof, many of them fell asleep almost as soon as the train left the station. Someone turned a radio on, and a fatuous song celebrating the construction of a highway bridge drowned out a dozen soft Spanish voices. I noticed a sign stuck to the back of the seat in front of me. It politely asked all passengers to be civilized enough to throw their garbage out the windows of the train.

I reached into my old canvas pack and pulled out a bundle of mail, which I quickly flipped through until I found the letter from Schultes that had been waiting for me at the Botanical Garden. Like everything about him, it was infused in sepia, the choice of language, the elegant handwriting, the tone of the letter itself, at once both intimate and formal like the correspondence of a Victorian gentleman. Schultes’s hope was that Tim Plowman would one day take over as director of the Botanical Museum, just as he had inherited the post from his mentor, the famous orchid specialist Oakes Ames. Thus, when Tim received his degree, Schultes had appointed him research associate, and together they had secured $250,000 from the U.S. Department of Agriculture—an enormous sum in those days—to study coca, the sacred leaf of the Andes and the notorious source of cocaine. For an ethnobotanist, it was a dream assignment.

In three pages Schultes outlined the details of the proposed expedition. Though long the focus of public concern and hysteria, he wrote, surprisingly little was known about coca. The botanical origins of the domesticated species, the chemistry of the leaf, the pharmacology of coca chewing, the plant’s role in nutrition, the geographical range of the cultivated varieties, the relationship between the wild and cultivated species—all these remained mysteries. He added that no concerted effort had been made to document the role of the coca in the religion and culture of Andean and Amazonian Indians since W. Golden Mortimer’s classic History of Coca, published in 1901. The letter continued in Schultes’s inimitable style—references to idiotic politicians and policies, an anecdote about one of the admixture plants used with coca that he had discovered in 1943, reflections on how much he had enjoyed chewing coca during the years he spent in the Amazon—but the essential point had been made. Plowman’s mandate from the U.S. government, made deliberately vague by Schultes, was to travel the length of the Andean Cordillera, traversing the mountains whenever possible, to reach the flanks of the montaña to locate the source of a plant known to the Indians as the divine leaf of immortality.

The expedition was to begin at Santa Marta. Flanked by the fetid marshlands of the Magdalena delta to the west and the stark desert of La Guajira peninsula to the east, the city is and has always been a smuggler’s paradise, the conduit through which flowed at one time perhaps a third of Colombia’s drug traffic. It is by reputation a seedy place, noisy by night, somnolent by day, and saturated at all hours by the scent of corruption. Just beyond the city to the southeast, however, lies a world apart: the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, the highest coastal mountain range on earth. Separated from the northernmost extension of the Andean Cordillera that forms the frontier with Venezuela to the east, the Sierra Nevada is an isolated volcanic massif, roughly triangular in shape, with sides a hundred miles long and a base running along the Caribbean coast. The northern face of the mountains rises directly from the sea to a height of over nineteen thousand feet in a mere thirty miles, a gradient surpassed only by that of the Himalayas.

The people of the Sierra are the Kogi and Ika, descendants of the ancient Tairona civilization that flourished on the coastal plain of Colombia for five hundred years before the arrival of Europeans. Since the time of Columbus, who met them on his third voyage, these Indians have resisted invaders by retreating from the fertile coastal plains higher and higher into the inaccessible reaches of the Sierra Nevada. In a bloodstained continent they alone have never been conquered.

A profoundly religious people, the Kogi and Ika draw their strength from the Great Mother, a goddess of fertility whose sons and daughters formed a pantheon of lesser gods who founded the ancient lineages of the Indians. To this day the Great Mother dwells at the heart of the world in the snow fields and glaciers of the high Sierra, the destination of the dead, and the source of the rivers and streams that bring life to the fields of the living. Water is the Great Mother’s blood, just as the stones are the tears of the ancestors. In a sacred landscape in which every plant is a manifestation of the divine, the chewing of hayo, a variety of coca found only in the mountains of Colombia, represents the most profound expression of culture. Distance in the mountains is not measured in miles but in coca chews. When two men meet, they do not shake hands, they exchange leaves. Their societal ideal is to abstain from sex, eating, and sleeping while staying up all night, chewing hayo and chanting the names of the ancestors. Each week the men chew about a pound of dry leaves, thus absorbing as much as a third of a gram of cocaine each day of their adult lives. In entering the Sierra to study coca, Tim was seeking a route into the very heart of Indian existence.

This letter from Professor Schultes, which I read in the yellow glow of dim lamps as the train shrieked and plunged in and out of tunnels through the Andean Cordillera, was like a map of dreams, a sketch of journeys he himself would be making were he still young and able. But nearly sixty, his body worn from years in the rain forest, it had been some time since he had been capable of active fieldwork. There was a certain tension in his writing, a sense of urgency that came from his awareness of both his own limitations and the speed with which the knowledge of the Indians was being lost and the forests destroyed. In this sense his letters were both gifts and challenges. It was impossible to read them without hearing his resonant voice, without feeling a surge of confidence and purpose, often strangely at odds with the esoteric character of the immediate assignments. This perhaps was the key to Schultes’s hold over his students. He had a way of giving form and substance to the most unusual of ethnobotanical pursuits. At any one time he had students flung all across Latin America seeking new fruits from the forest, obscure oil palms from the swamps of the Orinoco, rare tuber crops in the high Andes. Under his guidance it somehow made perfect sense to be lost in the canyons of western Mexico hunting for new varieties of peyote, miserably wet and cold in the southern Andes searching for mutant forms of the tree of the evil eagle, or hidden away in the basement of the Botanical Museum figuring out the best way to ingest the venom of a toad rumored to have been used as a ritual intoxicant by the ancient Olmec.

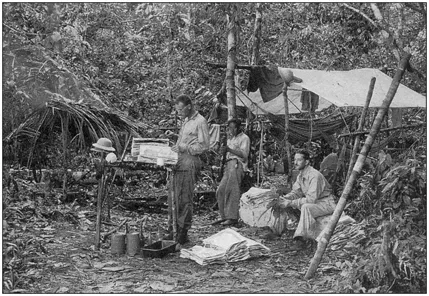

His own botanical achievements were legendary. In 1941, after having identified ololiuqui, the long-lost Aztec hallucinogen, and having collected the first specimens of teonanacatl, the sacred mushrooms of Mexico, he took a semester’s leave of absence from Harvard and disappeared into the Northwest Amazon of Colombia. Twelve years later he returned from South America having gone places no outsider had ever been, mapping uncharted rivers and living among two dozen Indian tribes while collecting some twenty thousand botanical specimens, including three hundred species new to science. The world’s leading authority on plant hallucinogens and the medicinal plants of the Amazon, he was for his students a living link to the great natural historians of the nineteenth century and to a distant era when the tropical rain forests stood immense, inviolable, a mantle of green stretching across entire continents.

At a time when there was little public interest in the Amazon and virtually no recognition of the importance of ethnobotanical exploration, Schultes drew to Harvard an extraordinarily eclectic group of students. He held court on the fourth floor of the Botanical Museum in the Nash Lecture Hall, a wooden laboratory draped in bark cloth and cluttered with blowguns, spears, dance masks, and dozens of glass bottles that sparkled with fruits and flowers no longer found in the wild. Oak cabinets elegantly displayed every known narcotic or hallucinogenic plant together with exotic paraphernalia—opium pipes from Thailand, a sacred mescal bean necklace from the Kiowa, a kilogram bar of hashish that went on display following one of Schultes’s expeditions to Afghanistan. In the midst of enough psychoactive drugs to keep the DEA busy for a year, Schultes would appear, tall and heavyset, dressed conservatively in gray flannels and thick oxfords, with a red Harvard tie habitually worn beneath a white lab coat. His face was round and kindly; his hair cut razor short, his rimless bifocals pressed tight to his face. He lectured from tattered pages, yellow with age, sometimes making amusing blunders that students jokingly dismissed as the side effects of his having ingested so many strange plants. Just the previous fall he had been discussing in class a drug that had been first isolated in 1943. “That was fourteen years ago,” he added, “and we’ve come a long way since.” Such oversights were easily forgiven, coming as they did from a fatherly professor who shot blowguns in class and at one time kept in his office a bucket of peyote buttons available to his students as an optional laboratory assignment.

Throughout the sixties, as America discovered the drugs that had fascinated Schultes for thirty years, his fame grew. Suddenly academic papers that had gathered dust in the library for decades were in fierce demand. His 1941 book on the psychoactive morning glory, A Contribution to our Knowledge of Rivea Corymbosa, the Narcotic Ololiuqui of the Aztecs, had been published on a hand-set printing press in the basement of the Botanical Museum. In the spring and summer of 1967 requests for copies poured into the museum, and florists across the nation experienced a run on packets of morning glory seeds, particularly the varieties named Pearly Gates and Heavenly Blue. Strange people began to make their way to the museum. A former graduate student tells of going to meet Schultes for the first time and finding two other visitors waiting outside his office, one of them passing the time by standing on his head like a yogi.

Schultes was an odd choice to become a sixties icon. His politics were exceedingly conservative. Neither a Democrat nor a Republican, he claimed to be a royalist who professed not to believe in the American Revolution. Wh...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- CHAPTER ONE Juan’s Farewell

- CHAPTER TWO Mountains of the Elder Brother

- CHAPTER THREE The Peyote Road 1936

- CHAPTER FOUR Flesh of the Gods 1938 39

- CHAPTER FIVE The Red Hotel

- CHAPTER SIX The Jaguar’s Nectar

- CHAPTER SEVEN The Sky Is Green and the Forest Blue 1941 42

- CHAPTER EIGHT The Sad Lowlands

- CHAPTER NINE Among the Waorani

- CHAPTER TEN White Blood of the Forest 1943

- CHAPTER ELEVEN The Betrayal of the Dream 1944 54

- CHAPTER TWELVE The Blue Orchid 1947 48

- CHAPTER THIRTEEN The Divine Leaf of Immortality

- CHAPTER FOURTEEN One River

- Notes on Sources

- Acknowledgments

- Index

- ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access One River by Wade Davis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Science & Technology Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.