- 464 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

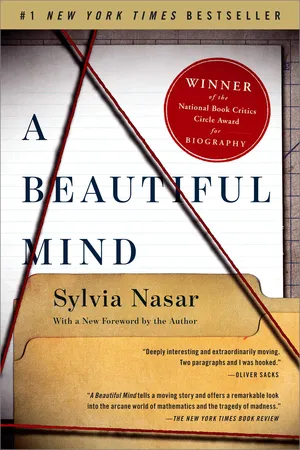

A Beautiful Mind

About this book

**Also an Academy Award–winning film starring Russell Crowe and Jennifer Connelly—directed by Ron Howard**

The powerful, dramatic biography of math genius John Nash, who overcame serious mental illness and schizophrenia to win the Nobel Prize.

“How could you, a mathematician, believe that extraterrestrials were sending you messages?” the visitor from Harvard asked the West Virginian with the movie-star looks and Olympian manner. “Because the ideas I had about supernatural beings came to me the same way my mathematical ideas did,” came the answer. “So I took them seriously.”

Thus begins the true story of John Nash, the mathematical genius who was a legend by age thirty when he slipped into madness, and who—thanks to the selflessness of a beautiful woman and the loyalty of the mathematics community—emerged after decades of ghostlike existence to win a Nobel Prize for triggering the game theory revolution. The inspiration for an Academy Award–winning movie, Sylvia Nasar’s now-classic biography is a drama about the mystery of the human mind, triumph over adversity, and the healing power of love.

The powerful, dramatic biography of math genius John Nash, who overcame serious mental illness and schizophrenia to win the Nobel Prize.

“How could you, a mathematician, believe that extraterrestrials were sending you messages?” the visitor from Harvard asked the West Virginian with the movie-star looks and Olympian manner. “Because the ideas I had about supernatural beings came to me the same way my mathematical ideas did,” came the answer. “So I took them seriously.”

Thus begins the true story of John Nash, the mathematical genius who was a legend by age thirty when he slipped into madness, and who—thanks to the selflessness of a beautiful woman and the loyalty of the mathematics community—emerged after decades of ghostlike existence to win a Nobel Prize for triggering the game theory revolution. The inspiration for an Academy Award–winning movie, Sylvia Nasar’s now-classic biography is a drama about the mystery of the human mind, triumph over adversity, and the healing power of love.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART ONE

A Beautiful Mind

1

Bluefield

1928–45

I was taught to feel, perhaps too much

The self-sufficing power of solitude.

—WILLIAM WORDSWORTH

AMONG JOHN NASH’S EARLIEST MEMORIES is one in which, as a child of about two or three, he is listening to his maternal grandmother play the piano in the front parlor of the old Tazewell Street house, high on a breezy hill overlooking the city of Bluefield, West Virginia.1

It was in this parlor that his parents were married on September 6, 1924, a Saturday, at eight in the morning to the chords of a Protestant hymn, amid basketfuls of blue hydrangeas, goldenrod, black-eyed susans, and white and gold marguerites.2 The thirty-two-year-old groom was tall and gravely handsome. The bride, four years his junior, was a willowy, dark-eyed beauty. Her narrow, brown cut-velvet dress emphasized her slender waist and long, graceful back. She had perhaps chosen its deep shade out of deference to her father’s recent death. She carried a bouquet of the same old-fashioned flowers that filled the room, and she wore more of these blooms woven through her thick chestnut hair. The effect was brilliant rather than subdued. The vibrant browns and golds, which would have made a woman with a lighter, more typically southern complexion look wan, embellished her rich coloring and lent her a striking and sophisticated air.

The ceremony, conducted by ministers from Christ Episcopal Church and Bland Street Methodist Church, was simple and brief, witnessed by fewer than a dozen family members and old friends. By eleven o’clock, the newlyweds were standing at the ornate, wrought-iron gate in front of the rambling, white 1890s house waving their goodbyes. Then, according to an account that appeared some weeks later in the Appalachian Power Company’s company newsletter, they embarked in the groom’s shiny new Dodge for an “extensive tour” through several northern states.3

The romantic style of the wedding, and the venturesome honeymoon, hinted at certain qualities in the couple, no longer in the first bloom of youth, that set them somewhat apart from the rest of society in this small American town.

John Forbes Nash, Sr., was “proper, painstaking, and very serious, a very conservative man in every respect,” according to his daughter Martha Nash Legg.4 What saved him from dullness was a sharp, inquiring mind. A Texas native, he came from the rural gentry, teachers and farmers, pious, frugal Puritans and Scottish Baptists who migrated west from New England and the Deep South.5 He was born in 1892 on his maternal grandparents’ plantation on the banks of the Red River in northern Texas, the oldest of three children of Martha Smith and Alexander Quincy Nash. The first few years of his life were spent in Sherman, Texas, where his paternal grandparents, both teachers, had founded the Sherman Institute (later the Mary Nash College for Women), a modest but progressive establishment, where the daughters of Texas’s middle class learned deportment, the value of regular physical exercise, and a bit of poetry and botany. His mother had been a student and then a teacher at the college before she married the son of its founders. After his grandparents died, John Sr.’s parents operated the college until a smallpox epidemic forced them to close its doors for good.

His childhood, spent within the precincts of Baptist institutions of higher learning, was unhappy. The unhappiness stemmed largely from his parents’ marriage. Martha Nash’s obituary refers to “many heavy burdens, responsibilities and disappointments, that made a severe demand on her nervous system and physical force.”6 Her chief burden was Alexander, a strange and unstable individual, a ne’er-do-well and a philanderer who either abandoned his wife and three children soon after the college’s demise or, more likely, was thrown out. When precisely Alexander left the family for good or what happened to him after he departed is unclear, but he was in the picture long enough to earn his children’s undying enmity and to instill in his youngest son a deep and ever-present hunger for respectability. “He was very concerned with appearances,” his daughter Martha later said of her father; “he wanted everything to be very proper.”7

John Sr.’s mother was a highly intelligent, resourceful woman. After she and her husband separated, Martha Nash supported herself and her two young sons and daughter on her own, working for many years as an administrator at Baylor College, another Baptist institution for girls, in Belton, in central Texas. Obituaries refer to her “fine executive ability” and “remarkable managerial skill.” According to the Baptist Standard, “She was an unusually capable woman. . . . She had the capacity of managing large enterprises . . . a true daughter of the true Southern gentry.” Devout and diligent, Martha was also described as an “efficient and devoted” mother, but her constant struggle against poverty, bad health, and low spirits, along with the shame of growing up in a fatherless household, left its scars on John Sr. and contributed to the emotional reserve he later displayed toward his own children.

Surrounded by unhappiness at home, John Sr. early on found solace and certainty in the realm of science and technology. He studied electrical engineering at Texas Agricultural & Mechanical, graduating around 1912. He enlisted in the army shortly after the United States entered World War I and spent most of his wartime duty as a lieutenant in the 144th Infantry Supply Division in France. When he returned to Texas, he did not go back to his previous job at General Electric, but instead tried his hand at teaching engineering students at Texas A&M. Given his background and interests, he may well have hoped to pursue an academic career. If so, however, those hopes came to nothing. At the end of the academic year, he agreed to take a position in Bluefield with the Appalachian Power Company (now American Electric Power), the utility that would employ him for the next thirty-eight years. By June, he was living in rented rooms in Bluefield.

Photographs of Margaret Virginia Martin — known as Virginia — at the time of her engagement to John Sr. show a smiling, animated woman, stylish and whippet-thin. One account called her “one of the most charming and cultured young ladies of the community.”8 Outgoing and energetic, Virginia was a freer, less rigid spirit than her quiet, reserved husband and a far more active presence in her son’s life. Her vitality and forcefulness were such that, years later, her son John, by then in his thirties and seriously ill, would dismiss a report from home that she had been hospitalized for a “nervous breakdown” as simply unbelievable. He would greet the news of her death in 1969 with similar incredulity.9

Like her husband, Virginia grew up in a family that valued church and higher education. But there the similarity ended. She was one of four surviving daughters of a popular physician, James Everett Martin, and his wife, Emma, who had moved to Bluefield from North Carolina during the early 1890s. The Martins were a well-to-do, prominent local family. Over time, they acquired a good deal of property in the town, and Dr. Martin eventually gave up his medical practice to manage his real-estate investments and to devote himself to civic affairs. Some accounts refer to him as a one-time postmaster, others as the town’s mayor. The Martins’ affluence did not protect them from terrible blows — their first child, a boy, died in infancy; Virginia, the second, was left entirely deaf in one ear at age twelve after a bout of scarlet fever; a younger brother was killed in a train wreck; and one of her sisters died in a typhoid epidemic — but on the whole Virginia grew up in a happier atmosphere than her husband. The Martins were also well-educated, and they saw to it that all of their daughters received university educations. Emma Martin was herself unusual in having graduated from a women’s college in Tennessee. Virginia studied English, French, German, and Latin first at Martha Washington College and later at West Virginia University. By the time she met her husband-to-be, she had been teaching for six years. She was a born teacher, a talent that she would later lavish on her gifted son. Like her husband, she had seen something beyond the small towns of her home state. Before her marriage, she and another Bluefield teacher, Elizabeth Shelton, spent several summers traveling and attending courses at various universities, including the University of California at Berkeley, Columbia University in New York, and the University of Virginia in Charlottesville.

When the newlyweds returned from their honeymoon, the couple lived at the Tazewell Street house with Virginia’s mother and sisters. John Sr. went back to his job at the Appalachian, which in those years consisted largely of driving all over the state inspecting remote power lines. Virginia did not return to teaching. Like most school districts around the country during the 1920s, the Mercer County school system had a marriage bar. Female teachers lost their jobs as soon as they married.10 But, quite apart from her forced resignation, her new husband had a strong feeling that he ought to provide for his wife and protect her from what he regarded as the shame of having to work, another legacy of his own upbringing.

• • •

Bluefield, named for the fields of “azure chicory” in surrounding valleys that grows along every street and alleyway even today, owes its existence to the rolling hills full of coal —“the wildest, most rugged and romantic country to be found in the mountains of Virginia or West Virginia” — that surround the remote little city.11 Norfolk & Western, in a spirit of “mean force and ignorance,” built a line in the 1890s that stretched from Roanoke to Bluefield, which lies in the Appalachians on the easternmost edge of the great Pocahontas coal seam. For a long time, Bluefield was a rough and ready outpost where Jewish merchants, African-American construction workers, and Tazewell County farmers struggled to make a living and where millionaire coal operators, most of whom lived ten miles away in Bramwell, battled Italian, Hungarian, and Polish immigrant laborers, and John L. Lewis and the UMW sat down with the coal operators to negotiate contracts, negotiations that often led to the bloody strikes and lockouts documented in John Sayles’s film Matewan.

By the 1920s, when the Nashes married, however, Bluefield’s character was already changing. Directly on the line between Chicago and Norfolk, the town was becoming an important rail hub and had attracted a prosperous white-collar class of middle managers, lawyers, small businessmen, ministers, and teachers.12 A real downtown of granite office buildings and stores had sprung up. Handsome churches had also gone up all over town. Snug frame houses with pretty little gardens edged by Rose of Sharon dotted the hills. The town had acquired a daily newspaper, a hospital, and a home for the elderly. Educational institutions, from private kindergartens and dancing schools to two small colleges, one black, one white, were thriving. The radio, telegraph, and telephone, as well as the railroads and, increasingly, the automobile, eased the sense of isolation.

Bluefield was not “a community of scholars,” as John Nash later said with mor...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Dedication

- Foreword

- Prologue

- Part One: A Beautiful Mind

- Part Two: Separate Lives

- Part Three: A Slow Fire Burning

- Part Four: The Lost Years

- Part Five: The Most Worthy

- Epilogue

- Acknowledgments

- Photographs

- About Sylvia Nasar

- Notes

- Select Bibliography

- Index

- Copyright

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access A Beautiful Mind by Sylvia Nasar in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Science & Technology Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.