- 432 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Selected as One of the Best Books of the 21st Century by The New York Times

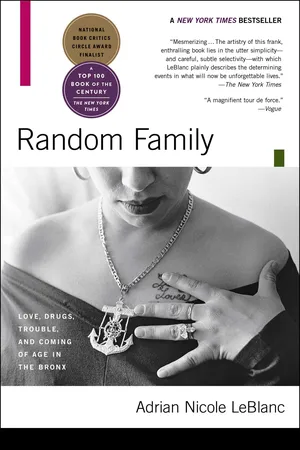

Set amid the havoc of the War on Drugs, this New York Times bestseller is an "astonishingly intimate" (New York magazine) chronicle of one family’s triumphs and trials in the South Bronx of the 1990s.

“Unmatched in depth and power and grace. A profound, achingly beautiful work of narrative nonfiction…The standard-bearer of embedded reportage.” —Matthew Desmond, author of Evicted

In her classic bestseller, journalist Adrian Nicole LeBlanc immerses readers in the world of one family with roots in the Bronx, New York. In 1989, LeBlanc approached Jessica, a young mother whose encounter with the carceral state is about to forever change the direction of her life. This meeting redirected LeBlanc’s reporting, taking her past the perennial stories of crime and violence into the community of women and children who bear the brunt of the insidious violence of poverty. Her book bears witness to the teetering highs and devastating lows in the daily lives of Jessica, her family, and her expanding circle of friends. Set at the height of the War on Drugs, Random Family is a love story—an ode to the families that form us and the families we create for ourselves.

Charting the tumultuous struggle of hope against deprivation over three generations, LeBlanc slips behind the statistics and comes back with a riveting, haunting, and distinctly American true story.

Set amid the havoc of the War on Drugs, this New York Times bestseller is an "astonishingly intimate" (New York magazine) chronicle of one family’s triumphs and trials in the South Bronx of the 1990s.

“Unmatched in depth and power and grace. A profound, achingly beautiful work of narrative nonfiction…The standard-bearer of embedded reportage.” —Matthew Desmond, author of Evicted

In her classic bestseller, journalist Adrian Nicole LeBlanc immerses readers in the world of one family with roots in the Bronx, New York. In 1989, LeBlanc approached Jessica, a young mother whose encounter with the carceral state is about to forever change the direction of her life. This meeting redirected LeBlanc’s reporting, taking her past the perennial stories of crime and violence into the community of women and children who bear the brunt of the insidious violence of poverty. Her book bears witness to the teetering highs and devastating lows in the daily lives of Jessica, her family, and her expanding circle of friends. Set at the height of the War on Drugs, Random Family is a love story—an ode to the families that form us and the families we create for ourselves.

Charting the tumultuous struggle of hope against deprivation over three generations, LeBlanc slips behind the statistics and comes back with a riveting, haunting, and distinctly American true story.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Random Family by Adrian Nicole LeBlanc in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Science Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

The Street

CHAPTER ONE

Jessica lived on Tremont Avenue, on one of the poorer blocks in a very poor section of the Bronx. She dressed even to go to the store. Chance was opportunity in the ghetto, and you had to be prepared for anything. She didn’t have much of a wardrobe, but she was resourceful with what she had—her sister’s Lee jeans, her best friend’s earrings, her mother’s T-shirts and perfume. Her appearance on the streets in her neighborhood usually caused a stir. A sixteen-year-old Puerto Rican girl with bright hazel eyes, a huge, inviting smile, and a voluptuous shape, she radiated intimacy wherever she went. You could be talking to her in the middle of the bustle of Tremont and feel as if lovers’ confidences were being exchanged beneath a tent of sheets. Guys in cars offered rides. Grown men got stupid. Women pursed their lips. Boys made promises they could not keep.

Jessica was good at attracting boys, but less good at holding on to them. She fell in love hard and fast. She desperately wanted to be somebody’s real girlfriend, but she always ended up the other girl, the mistress, the one they saw on the down-low, the girl nobody claimed. Boys called up to her window after they’d dropped off their main girls, the steady ones they referred to as wives. Jessica still had her fun, but her fun was somebody else’s trouble, and for a wild girl at the dangerous age, the trouble could get big.

It was the mideighties, and the drug trade on East Tremont was brisk. The avenue marks the north end of the South Bronx, running east to west. Jessica lived just off the Grand Concourse, which bisects the Bronx lengthwise. Her mother’s tenement apartment overlooked an underpass. Car stereos thudded and Spanish radio tunes wafted down from windows. On corners, boys stood draped in gold bracelets and chains. Children munched on the takeout that the dealers bought them, balancing the styrofoam trays of greasy food on their knees. Grandmothers pushed strollers. Young mothers leaned on strollers they’d parked so they could concentrate on flirting, their irresistible babies providing excellent introductions and much-needed entertainment. All along the avenue, working people shopped and dragged home bags of groceries, or pushed wheelcarts of meticulously folded laundry. Drug customers wound through the crowd, copped, and skulked away again. The streets that loosely bracketed Jessica’s world—Tremont and Anthony, Anthony and Echo, Mount Hope and Anthony, Mount Hope and Monroe—were some of the hottest drug-dealing blocks in the notorious 46th Precinct.

The same stretch of Tremont had been good to Jessica’s family. Lourdes, Jessica’s mother, had moved from Manhattan with a violent boyfriend, hoping the Bronx might give the troubled relationship a fresh start. That relationship soon ended, but a new place still meant possibility. One afternoon, Jessica stopped by Ultra Fine Meats for Lourdes and the butcher asked her out. Jessica was fourteen at the time; he was twenty-five. Jessica replied that she was too young for him but that her thirty-two-year-old mother was pretty and available. It took the butcher seven tries before Lourdes agreed to a date. Two months later, he moved in. The children called him Big Daddy.

Almost immediately, the household resumed a schedule: Lourdes prepared Big Daddy’s breakfast and sent him off to work; everyone—Robert, Jessica, Elaine, and Cesar—went to school; Lourdes cleaned house and had the evening meal cooked and waiting on the stove by noon. Big Daddy seemed to love Lourdes. On weekends, he took her bowling, dancing, or out to City Island for dinner. And he accepted her four children. He bought them clothes, invited them to softball games, and drove them upstate for picnics at Bear Mountain. He behaved as though they were a family.

Jessica and her older brother, Robert, had the same father, who had died when Jessica was three, but he had never accepted Jessica as his; now only Robert maintained a close relationship with the father’s relatives. Elaine, Jessica’s younger sister, had her own father, whom she sometimes visited on weekends. Cesar’s father accepted him—Cesar had his last name on his birth certificate—but he was a drug dealer with other women and other kids. Occasionally he passed by Lourdes’s; sometimes Cesar went to stay with him, and during those visits, Cesar would keep him company on the street. Cesar’s father put him to work: “Here,” he would say, passing Cesar vials of crack taped together, “hold this.” Drug charges didn’t stick to children, but Big Daddy cautioned Cesar about the lifestyle when he returned home. “Don’t follow his lead. If anybody’s lead you gonna follow, it should be mine.” Big Daddy spoke to Cesar’s teachers when Cesar had problems in school. Jessica considered Big Daddy a stepfather, an honor she had not bestowed upon any other of her mother’s men. But even Jessica’s and Cesar’s affection for Big Daddy could not keep them inside.

For Jessica, love was the most interesting place to go and beauty was the ticket. She gravitated toward the enterprising boys, the boys with money, who were mostly the ones dealing drugs—purposeful boys who pushed out of the bodega’s smudged doors as if they were stepping into a party instead of onto a littered sidewalk along a potholed street. Jessica sashayed onto the pavement with a similar readiness whenever she descended the four flights of stairs from the apartment and emerged, expectant and smiling, from the paint-chipped vestibule. Lourdes thought that Jessica was a dreamer: “She always wanted to have a king with a maid. I always told her, ‘That’s only in books. Face reality.’ Her dream was more upper than herself.” Lourdes would caution her daughter as she disappeared down the dreary stairwell, “God ain’t gonna have a pillow waiting for your ass when you fall landing from the sky.”

Outside, Jessica believed, anything could happen. Usually, though, not much did. She would go off in search of one of her boyfriends, or disappear with Lillian, one of her best friends. Her little brother, Cesar, would run around the neighborhood, antagonizing the other children he half-wanted as friends. Sometimes Jessica would cajole slices of pizza for Cesar from her dates. Her seductive ways instructed him. “My sister was smart,” Cesar said. “She used me like a decoy, so if a guy got mad at her, he would still come around to take me out. ‘Here’s my little brother,’ she would say. ‘Take him with you.’ ” More often, though, Cesar got left behind. He would sit on the broken steps of his mother’s building, biding his time, watching the older boys who ruled the street.

Jessica considered Victor a boyfriend, and she’d visit him on Echo Place, where he sold crack and weed. Victor saw other girls, though, and Jessica was open to other opportunities. One day in the fall of 1984, when she should have been in school, she and Lillian went to a toga party on 187th and Crotona Avenue. The two friends were known at the hooky house on Crotona. The girls would shadow the boys on their way to the handball courts or kill time at White Castle burgers, and everyone often ended up in the basement room. The building was officially abandoned, but the kids had made a home there. They’d set up old sofas along one wall, and on another they’d arranged a couple of beds. There was always a DJ scratching records. The boys practiced break dancing on an old carpet and lifted weights. The girls had little to do but watch the boys or primp in front of the salvaged mirrors propped beside a punching bag. At the toga party, Jessica and Lillian entered one of the makeshift bedrooms to exchange their clothes for sheets. Two older boys named Puma and Chino followed them. The boys told the girls that they were pretty, and that their bodies looked beautiful with or without sheets. As a matter of fact, they said, instead of joining the party, why don’t we just stay right here?

Puma dealt drugs, but he was no ordinary boy. He had appeared in Beat Street, a movie that chronicled the earliest days of hip-hop from the perspective of the inner-city kids who’d created it. The film, which would become a cult classic, portrayed self-expression as essential to survival, along with mothers, friends, money, music, and food. Beat Street showcased some Bronx talent, including Puma’s group, the Rock Steady Crew. Puma had cinematic presence, and he was a remarkable break-dancer, but when he met Jessica his career was sliding to the bottom of its brief slope of success. The international tour that had taken him to Australia and Japan was over, and the tuxedo he’d worn break dancing for the queen of England hung in a closet in its dry-cleaning bag. He’d spent all the money he had earned on clothes and sneakers and fleets of mopeds for his friends.

Jessica was glad for anybody’s attention, but she was especially flattered by Puma’s. He was a celebrity. He performed solo for her. He was clever, and his antic behavior made her laugh. One thing led to another, and next thing you know, Jessica and Puma were kissing on top of a pile of coats. Similar things were happening between Lillian and Chino on another bed.

Both girls came out pregnant. Jessica assured her mother that the father was her boyfriend, Victor, but there was no way to be certain. The following May, Jessica and Lillian dropped out of ninth grade. They gave birth to baby girls four days apart, in the summer of 1985. Big Daddy clasped Jessica’s hand through her delivery. At one point, Jessica bit him so hard that she drew blood. The grandfather scar made Big Daddy proud.

Jessica named her daughter Serena Josephine. Lourdes promptly proclaimed her Little Star. It was understood that Lourdes would have to raise her; Jessica didn’t have the patience. Even if she hadn’t been young, and moody, Jessica wasn’t the mothering kind. Lourdes wasn’t, either—in fact, she wished she’d never had children—but circumstance had eroded her active resistance to the role. She’d been raising children since she was six. First, she’d watched her own four siblings while her mother worked double shifts at a garment factory in Hell’s Kitchen. She’d fought their neighborhood fights. She’d fed them and bathed them and put them to bed. Now Lourdes’s own four, whom she had been able to manage when they were little, were teenagers slipping beyond her reach.

Robert and Elaine had been easy, but Lourdes felt their fathers’ families were turning them into snobs. Robert returned from his weekend visits with his grandmother smoldering with righteousness. Lourdes could tell he disapproved of her involvement with Santeria, but who was her son to judge? How holy had it been, when Jessica was pregnant, for Robert to chase her around the apartment, threatening to beat her up? Her daughter Elaine’s arrogance occupied a more worldly terrain. On Sunday nights, she alighted from her father’s yellow cab, prim in her new outfits, and turned up her cute nose at the clothes Lourdes had brought home from the dollar store.

Jessica and Cesar were Lourdes’s favorites, but they ignored her advice and infuriated her regularly. When Lourdes stuck her head out of the living room window overlooking Tremont and called her children in for supper (she used the whistle from the sound track of the movie The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly), she was usually calling for Jessica and Cesar; Robert and Elaine were apt to be at home. Robert and Elaine worried about getting into trouble, whereas Jessica and Cesar had as much fun as they possibly could until trouble inevitably hit. Robert and Elaine were dutiful students. Jessica and Cesar were smart, but undisciplined. Jessica cut classes. Cesar sprinted through his work, then found it impossible to sit still; once, he’d jumped out of his second-story classroom window after Lourdes had physically dragged him around the corner to school.

Jessica and Cesar also looked out for each other. One night, Jessica went missing and Lourdes found out that she had been with an off-duty cop in a parked car; when Lourdes kicked Jessica in the head so hard that her ear bled, it was Cesar who ran to the hospital for help. Another time, during an electrical fire, Jessica ushered Cesar to the safety of the fire escape. Jessica knew how to appease Lourdes’s brooding with cigarettes and her favorite chocolate bead candy. Cesar, however, had fewer resources at his disposal. He had learned to steel himself against his mother’s beatings. By the time he was eleven, when his niece Little Star was born, Cesar didn’t cry no matter how hard Lourdes hit.

For Lourdes, Little Star’s arrival was like new love, or the coming of spring. As far as she was concerned, that little girl was hers. “When I pulled that baby out—Jessica was there—the eyes!” Lourdes said. “The eyes speak faster than the mouth. The eyes come from the heart.” A baby was trustworthy. Little Star would listen to Lourdes and mind her; she would learn from Lourdes’s mistakes. Little Star would love her grandmother with the unquestioning loyalty Lourdes felt she deserved but didn’t get from her ungrateful kids.

Meanwhile, Jessica made the most of her ambiguous situation. She told Victor that he was the father: she and Victor cared for one another and he had attended the delivery; he also gave Jessica money for Little Star’s first Pampers, although his other girlfriend was pregnant, too. Secretly, however, Jessica hoped that Puma was the father, and she was also telling him that the baby was his. Puma was living with a girl named Trinket, who was pregnant, and whom he referred to as his wife; he also had another baby by Victor’s girlfriend’s sister. Despite the formidable odds, Jessica hoped for a future with him.

Publicly, Puma insisted Little Star was not his. But she certainly looked like his: she had the same broad forehead, and that wide gap between her dot-brown eyes. The day Jessica came home with a videotape of the movie Beat Street, Lourdes had heard enough about this breakdancing Puma to go on alert. She settled on her bed with Little Star, Jessica, Elaine, and their dog, Scruffy. In one of the early scenes of the film, a boy who looked suspiciously like Little Star did a speedy break dance at a hooky house. Then he challenged a rival crew to a battle at the Roxy, a popular club.

“Hold that pause,” shouted Lourdes. “That’s Little Star’s father! I will cut my pussy off and give it to that dog if that ain’t Little Star’s father!” Jessica laughed, pleased at the recognition. Puma could say what he liked, but blood will out.

Puma’s confidante was a short, stocky tomboy named Milagros. Milagros had known Puma forever and considered him family. Puma was the first boy she’d ever kissed. Kissing boys no longer interested Milagros. Puma’s stories of Jessica’s sexual escapades, however, intrigued her; Milagros had noticed Jessica as well, when they both attended Roosevelt High School. Milagros knew that Puma still saw Jessica, but she kept it to herself. Meanwhile, Milagros and Puma’s live-in girlfriend, Trinket, were becoming friends.

Milagros and Trinket made an unlikely duo. If a river ran through the styles of poor South Bronx girlhood, these two camped on opposite banks. Milagros, who never wore makeup, tugged her dull brown hair into a pull-back and stuck to what she called “the simple look”—T-shirts, sneakers, jeans. Trinket slathered on lipstick, painted rainbows of eye shadow on the lids of her green eyes, and teased her auburn hair into a lion’s mane. Trinket was looking forward to becoming a mother, whereas Milagros proclaimed, loudly and often, her tiny nostrils flaring, that she would never have children and end up slaving to a man.

In the fall of 1985, some of Jessica’s friends returned to school. Bored and left behind, Jessica became depressed. She would page Puma, and once in a while he would call her back. Sometimes Jessica went looking for him in Poe Park, a hangout near Kingsbridge and Fordham Road, where the Rock Steady Crew occasionally performed. Usually, though, she found Puma at work, standing on a corner not far from the hooky house. Jessica had little chance of running into Trinket at his drug spot because Puma urged his wife to stay away. Alone with Puma, Jessica broached the touchy subject of what was between them: “Give time for her features to de...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Dedication

- Part I: The Street

- Part II: Lockdown

- Part III: Upstate

- Part IV: House to House

- Part V: Breaking Out

- Author’s Note

- Acknowledgments

- Reading Group Guide

- About Adrian Nicole LeBlanc

- Copyright