- 348 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

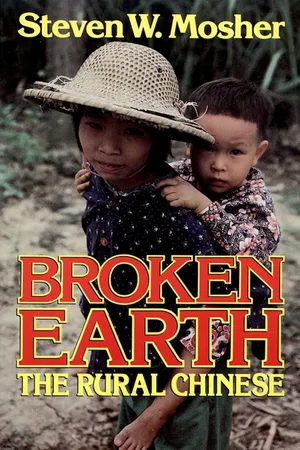

Broken Earth

About this book

An anthropologist and Sinologist, Stephen W. Mosher, lived and worked in rural China in late 1979 and early 1980. His shocking revelations about conditions there have earned him the condemnation of the Beijing (Peking) government, which denounces him as a "foreign spy."

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 Introduction: Beyond the Chinese Shadow Play

* … under the conditions in which foreign residents and visitors now live in the People’s Republic of China, it is impossible to write anything but frivolities, and those who think they can do something serious when reporting their Chinese experiences, or who pretend they describe Chinese realities when they are in fact describing the Chinese shadow play produced by Maoist authorities, either deceive their readers or, worse, delude themselves.

Simon Leys

Late in March 1979 I first arrived, elated yet diffident, in the South China commune that I hoped to study. As an anthropologist whose goal it was to penetrate the private world of the villager, I saw getting through to the Chinese as people as the main challenge of the coming year. I was an outsider, neither Chinese nor Communist, and I wondered how long it would take to make contacts with local peasants and cadres, and worried that it might not be possible at all.

Friends who had been to the People’s Republic had not been optimistic about my chances. One acquaintance, just back from a year of intensive study of Chinese at the Beijing Language Institute, told me how he had been put up by the PRC government in a dormitory restricted to foreign students where he had met and made friends with Australians, Germans, Africans—students of various nationalities—but no Chinese. His instructors at the institute had been the only Chinese he had come into regular contact with. While they had been cordial enough in class, they had discouraged socializing after hours. His trips about the city of Beijing, to such places as Tiananmen Square, Beihai Park, and the Forbidden City, had engulfed him in vast, swirling crowds of people but had not helped him to break through the social barriers that separated him from these Chinese millions. Outside of the institute he had been treated as a walking spectacle, interesting to observe but dangerous to approach too closely. People stared at him, pointed him out to their companions, but generally avoided talking to him, unless it was about some simple matter such as directions to a nearby restaurant or bus stop. Exchanging names or dinner invitations was out of the question. He had not set foot in a single Chinese home during his year in Beijing, and despaired that he could have made more Chinese friends by staying in California. “You will get to know Chinese in their official roles as cadres, teachers, and Communist Party members,” he warned bleakly, “but you will not get to know them as people.”

At first this pessimistic appraisal seemed to be coming true, at least in my relations with cadres (the Chinese term for officials of all stripes), who were invariably polite, correct, and standoffish. It was as if each cadre carefully wrapped himself in a private Bamboo Curtain of political orthodoxy that made the easy friendships and open give-and-take that Westerners are accustomed to impossible. But I soon had an experience which taught me that under the right circumstances this barrier of reserve could come down.

One morning I paid a visit, arranged in advance through the local “foreign affairs” cadre, to Equality Commune’s industry and transportation department, which was responsible for the administration of the commune’s twenty-odd factories. I was taken to the office of Jian Liguo, who was introduced to me as one of the leading cadres of the zhanxian, or department (literally, battle line). Jian offered me a seat at one end of the green felt-covered table which took up nearly half of his small office, while he and two other ranking officials took seats at the opposite end. For the next two hours we discussed the work of the “battle line” that they were in charge of, covering a wide range of topics from the organization of local industry to the day-to-day work of the department staff. My questions about current problems in production or with personnel, however, met with only the briefest comment.

Still, despite their stonewalling where difficulties were concerned, I learned a great deal about the work of the department during the course of the morning, and I offered my genuine thanks to the cadres for their cooperation as the interview ended. After the Chinese fashion, all three courteously ferried me down the stairs to the building’s entrance to see me on my way, and Jian Liguo even walked with me the final few paces to where I had parked my bike. As we bade farewell, out of earshot of the other two cadres, who had already turned to go back inside, he casually invited me over to his house. “If you have time one of these evenings, why don’t you come over and sit for a while,” he said. Though his invitation was tendered with the usual Chinese diffidence (no Chinese would ever say, “We must get together again”—it would sound too much like an imperial summons), I was struck by an underlying earnestness, and immediately asked him when would be most convenient. Before we parted, we had agreed that I would call at his home the following evening.

The next night I waited until 8 P.M. before setting out by bicycle for the village where Jian Liguo lived. By that hour, to avoid the damp chill of March evenings, most peasants had retreated to the relative warmth of their homes, and I found the road deserted. I rode slowly along, picking out a path by means of the flashlight I held in one hand, trying to avoid the worst of the potholes that pitted the dirt surface of the road. Reaching Jian’s village, I dismounted and entered the narrow, stone-paved alley leading to the village center that he had described. The high walls of the houses loomed over the alley, leaving it in a pitch darkness unbroken by street lights, and I flicked on my flashlight at intervals to pick out my way. I came to Jian’s doorstep pleased that I had not encountered a single person.

The double wooden doors of Jian’s outer gate stood ajar, and, like a villager, I stepped into his courtyard without knocking and called out his nickname, Old Jian. A moment later he stuck his head out of the door of the house proper and, seeing who it was, stepped out and greeted me with obvious pleasure. He came out, took me by the arm, and led me inside. I stepped over the threshold of his house and received my first surprise of the night. His living room was packed with twenty or more peasants, seated on wooden stools or simply squatting on the floor. Sensing my pang of uncertainty, Jian gestured at the roomful of watchers and told me that they came to his house to watch television for an hour or two after dinner on the nights when there was electricity. “Tonight there is a Hong Kong kungfu program on,” he went on, “so the crowd is especially large.” As he was speaking, I noted that they were indeed all intently watching the TV set in the far corner of the room. My entrance had caused scarcely a ripple.

Jian invited me to sit down in a chair away from the TV and went to make a pot of tea. His living room, with its set of lacquered if plain wooden furniture and its tiled floor, seemed to me to be a class above those of the other village homes I had been in, which usually had only a motley collection of battered and pock-marked furniture placed haphazardly about a packed earth floor. As a commune cadre, Jian obviously had good local connections, and benefited as well from occasional remittances from Hong Kong relatives, to judge from the TV set. Jian returned with the tea, which we sipped as we waited for the program to end, talking pleasantries. He pointed out with pride that he had fashioned the TV antenna himself, confiding that it was one of only two in the village, out of a total of twelve sets, that could consistently receive broadcasts from Hong Kong 45 miles down the Pearl River. The reception did not seem good to me that evening. The kungfu fighters leaped and feinted through a miniature blizzard of snow and challenged one another through the crackle of static, but this did not seem to distract the villagers, who were totally absorbed in the action.

The program over, Jian flicked off his TV set. The peasants stood slowly up, shouldered their stools, and unhurriedly began to file out of the room. Only then did they take me in, young and old alike staring at me with the unblinking yet benign stares of so many roughhewn children. Some of the men glanced at Jian, as if to ask what could have brought this foreigner to his house so late at night. At least that’s the way I uneasily read their expressions, and I wondered again if I had made a mistake in coming here. Jian seemed to sense my thoughts, smiled again—he was certainly much more expansive at home than when engaged at the “battle line”—and told me, even while the last of the peasants were still shuffling out of his house, that they were only peasant neighbors of his and that it made little difference what they thought about my presence. (He later told me outright that it was his commune comrades that he had to be careful of. No one really listened very much to the peasants, he maintained, but it would go badly for him politically if he allowed the people he worked with to get anything on him.)

Then his mood became serious, and, without prompting, he opened up to me. I said very little about anything during the next several hours, concentrating rather on listening and taking notes. He poured out no-holds-barred assessments of his own “battle line” (“Only a handful of our commune enterprises make a profit, though the accounts are jimmied to show that they all do”), the local medical care system (“poorly administered and of low quality”), the political system (“The problem is the system itself, which needs a thorough overhaul”), and the several decades of Communist rule (“It was the Hundred Flowers campaign of 1957 that made everyone first question where the Communist Party was taking us”). So it continued until after 1 A.M., when, my notetaking falling ever further behind his narrative, I suggested that we stop for now and meet again a few nights hence, after I had had a chance to absorb and think about what he had told me. We settled on the following week, and I took my leave, though not before he cautioned me to keep quiet about this late-night visit.

I rode slowly home, amazed at how much I had learned in a single evening about how the commune world looked from the inside, and even more astounded over Jian’s transformation from a loyal, by-the-book cadre to a sharp-tongued social and political critic. He had clearly exulted in the opportunity to speak his mind freely, something that he told me he was able to do only in the company of trusted friends, and then only in small groups of two or three. Why he had decided he could trust me as well, after we had only met once for a rather formal interview, was initially a mystery to me, but as a result of this decision he had relaxed his carefully conditioned political reflexes and had become honest and outspoken.

What was remarkable about this transformation, apart from the fact that it occurred at all, was that it was total. Rather than the gradual, stepwise progression to mutual trust and intimacy that marks Western confidences, it was a sudden plunge into personal confession that left no subject, even politics, taboo. I was so taken aback at first by Jian’s unexpected revelations concerning politics that I briefly suspected entrapment, worrying that his remarks might be a ruse to trick me into making comments unfavorable to the Beijing regime, at which point I imagined a trio of public security agents would appear in the room and my stay in the PRC would be over. I even asked him to show me around his house, under this pretext satisfying myself that, except for the members of his immediate family, who had just gone to bed, the two of us were alone. Later, after I came to better understand Jian, I had to laugh at my momentary fear that he was an actor in a scheme to entrap me.

Yet Jian was an actor of sorts. Like everyone in China with the exception of the peasants, Jian wore a mask of political orthodoxy in public, carefully projecting the image sanctioned by the state. (“People here are very, very careful about what they say and how they behave in public,” a rural physician confirmed to me.) At home, in the company of someone he trusted, Jian’s mask came off and he could be himself—a warm, spontaneous, and remarkably free-thinking human being. By unmasking himself, Jian had given me my first glimpse of the human face of China, and it was considerably different than I had been led to expect.

As my stay in China lengthened and numerous other Chinese took me into their confidence as Jian Liguo had, the sterility of conventional images of the People’s Republic became increasingly apparent. Everywhere I looked, the richly complex reality of Chinese life, with its fascinating irregularities of opinion and behavior, seemed to deflate, if not demolish, exaggerated or romantic clichés about socialist China. Though I had long since set aside the myth of monolithic Chinese communism, I was still unprepared to hear a young Communist Party member mock Mao’s famous bluster that the United States is only a paper tiger. “We are the paper tiger,” he told me. Despite being suspicious of Beijing’s claim that the PRC has left feudalism behind in its march toward the socialist millennium, I was still taken aback to hear the Party secretary of a production brigade complain to me that the nationwide birth control campaign was making it difficult for his clan to attain its rightful, pre-World War II size.

Few socialist clichés survived careful and lengthy scrutiny. I found that instead of being unflagging builders of socialism, peasants work a lethargic six hours a day for the collective and spend their remaining time tirelessly cultivating their private plots, feeding their domestic animals, and selling their produce on the free market; that in a country that espouses state and collective ownership of property, most people still own the homes they live in, and build new homes themselves when their families grow large and divide; that many Chinese—peasants, workers, and cadres alike—are alienated from politics by the endless cycle of political movements that the quixotic Mao sent hurtling down on their heads; that in a state where equality of the sexes is not only a law but a point of official pride, women do almost no administrative work, nearly all domestic work, and a good half of collective work; that despite efforts by the Communist Party to instill in its cadres a new morality of selfless devotion to the common good (“Serve the people”), the Chinese I spoke with insisted that most cadres look out for their own interests first, last, and always; that despite decades of political conditioning by the world’s best-coordinated propaganda machine, most Chinese retain their traditional values and beliefs.

I knew beforehand that the state’s efforts to create “new socialist men” out of China’s peasant masses had not been entirely successful, but I was still surprised at the traditional ways villagers ordered their lives. Village temples had been mostly destroyed or converted to collective headquarters during the “Great Leap Forward” (GLF), but I discovered that most villagers still worshipped the gods regularly on the first and fifteenth of the lunar month in the privacy of their home. Ancestral tablets had been marked for burning during the “Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution” (GPCR), but peasants told me how they had hidden the inscribed tablet itself, casting only its wooden frame on the bonfire, and continued to memorialize their forebears on the prescribed days behind closed doors. As the months passed, I saw that peasants still feast on festival days, marry on “lucky” days, pay bride prices for new daughters-in-law, celebrate births with full-month ceremonies, prefer sons to daughters, invite Taoist priests to chant following a death in the family, bury their dead on “lucky” days, and then rebury them seven years later in “golden pagodas” set above ground in a “lucky” spot.

I also had to learn that despite the state’s vow to reduce material inequality, cadres and the well connected led much more comfortable lives than their less influential neighbors. The findings of Western scholarship, that rich peasants in rural collectives earn only twice as much as poor peasants, held true for the villages I visited as well, but turned out to matter far less than I had originally imagined. Money alone counts for little, I was told repeatedly by Chinese friends, who never tired of complaining that they had “money but nothing to buy.” They explained that not only is the production of consumer goods insufficient to meet demand, but the bicycles, tape recorders, and television sets that are produced go to those who have guanxi (connections) or ganqing (influence or sentiment) with key cadres that can be manipulated so one can zou-houmen (go in the back door). The annual quota of bicycles allotted to every village, for example, is spoken for well beforehand by peasants who are either related to or on good terms with, or in desperation have bribed, the cadre in charge of distributing what the peasants revealingly term “treasures.”

It was this ineradicable selfishness in a system predicated on selflessness that dispelled for me the propaganda vision of socialism in the making. I was not overly surprised to find that individuals and families were still motivated primarily by personal or familial gain, for I had surmised in advance that they had not been radically transformed, but I had not been expecting collectives—production brigades and their constituent production teams—originally created by the state to have been captured by the peasants, who use them to advance their own interests. I did not fully come to see how particularistic and partisan the rural Chinese remained, however, and how openly they violated socialist mores both individually and in groups, until I was told by a young teacher about the misadventures of an attempt by the Guangzhou (Canton) municipality to build a middle school in Longwei County, a poor county located in the mountainous periphery of the municipal area and well in need of better educational facilities. School district officials located a building site for the proposed school on uncultivated land near the road which linked the county seat to Guangzhou. They then approached the local production team—the lowest level of collective agriculture, under the production brigade and commune—whose hamlet lay nearest the projected site to discuss terms. The team head asked only a modest annual rent of 100 renminbi, or rmb,* for the approximately 5 acres of land, or roughly the value of the wild herbs and firewood formerly gathered off that plot each year, and readily agreed to provide laborers to help with the construction of the school. He would cooperate fully with the state’s effort to help his culturally backward district, he assured the visiting cadres. They then returned to Guangzhou, pleased that the negotiations had gone so smoothly, and a dozen teachers were sent to supervise the construction of the school and start classes.

Then the demands began. The team head first requested an indefinite loan of 2,000 rmb ($1,333) from the school, and the newly appointed school principal had no choice but to comply. Then the head insisted that the laborers he was sending over be paid 1 rmb ($0.67) a day, or three times what they normally earned in collective work. Next came a demand that the school “lend” the production team enough bricks and cement from the stockpiled building materials to allow the construction of a sizable grain storage silo. Worst of all, nearly all of the twenty-odd families in the team had taken advantage of the convenient store of nearby materials to begin replacing their original huts of thatch and mud brick with new homes of fired brick with tile roofs.

With supplies disappearing almost as fast as they were shipped in, the beleaguered teachers decided in desperation to take up residence at the building site itself and moved into the four classrooms that had been completed by that point. Their presence proved to have little effect, however. The peasants kept pushing their wheelbarrows over to the building site, loading up a 50-kilogram bag of cement or a barrow of bricks, and shoving off for home to continue work on their half-completed houses. If their piracy chanced to be discovered by a teacher, they would sing out cheerfully, without a trace of embarrassment, “Just borrowing a bag of concrete” or “load of bricks, teacher,” and trundle off with their prize. The teachers were furious, but there was little they could do. “We couldn’t complete the school without their assistance, and they knew it,” the teacher I talked with said helplessly. “And if we had really tried to stop their thefts, they probably would have broken all of the windows in the schoolhouse or worse.” Senior cadres from the brigade and commune to which the production team belonged simply shrugged their shoulders when approached by the teachers for aid, my informant said. “This is a very poor area, they would say, as if that explained everything.”

The unruly richness and anarchic complexity of Chinese life has remained largely hidden from the view of Western observers, in part obscured by the flat projections of official propagandists and Maoist apologists, in part because opportunities for Chinese and foreigners to associate in the PRC openly and easily are few. There are a formidable series o...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Contents

- 1 Introduction: Beyond the Chinese Shadow Play

- 2 Village Life The Chinese Peasant at Home

- 3 The System The Iron Cage of Bureaucracy

- 4 Corruption The Art of Going in the Back Door

- 5 Childhood Learning to Be Chinese and Communist

- 6 Youth Coming of Age in the Cultural Revolution

- 7 Sex Love and Marriage Public Repression Covert Expression

- 8 Women The Socialist Double Bind

- 9 Birth Control A Grim Game of Numbers

- 10 Political Campaigns The Human Costs of Social Engineering

- 11 Political Myths Peasants Progress and the “New China”

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Broken Earth by Steven W. Mosher in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.