- 480 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

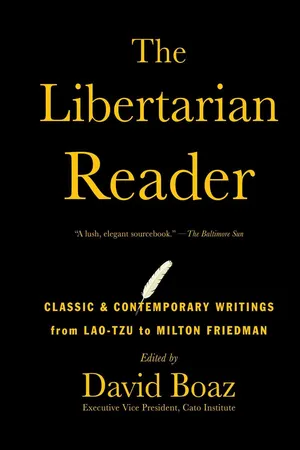

The first collection of seminal writings on a movement that is rapidly changing the face of American politics, The Libertarian Reader links some of the most fertile minds of our time to a centuries-old commitment to freedom, self-determination, and opposition to intrusive government. A movement that today counts among its supporters Steve Forbes, Nat Hentoff, and P.J. O'Rourke, libertarianism joins a continuous thread of political reason running throughout history.

Writing in 1995 about the large numbers of Americans who say they'd welcome a third party, David Broder of The Washington Post commented, "The distinguishing characteristic of these potential independent voters—aside from their disillusionment with Washington politicians of both parties—is their libertarian streak. They are skeptical of the Democrats because they identify them with big government. They are wary of the Republicans because of the growing influence within the GOP of the religious right."

In The Libertarian Reader, David Boaz has gathered the writers and works that represent the building blocks of libertarianism. These individuals have spoken out for the basic freedoms that have made possible the flowering of spiritual, moral, and economic life. For all independent thinkers, this unique sourcebook will stand as a classic reference for years to come, and a reminder that libertarianism is one of our oldest and most venerable American traditions.

Writing in 1995 about the large numbers of Americans who say they'd welcome a third party, David Broder of The Washington Post commented, "The distinguishing characteristic of these potential independent voters—aside from their disillusionment with Washington politicians of both parties—is their libertarian streak. They are skeptical of the Democrats because they identify them with big government. They are wary of the Republicans because of the growing influence within the GOP of the religious right."

In The Libertarian Reader, David Boaz has gathered the writers and works that represent the building blocks of libertarianism. These individuals have spoken out for the basic freedoms that have made possible the flowering of spiritual, moral, and economic life. For all independent thinkers, this unique sourcebook will stand as a classic reference for years to come, and a reminder that libertarianism is one of our oldest and most venerable American traditions.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART ONE

SKEPTICISM ABOUT POWER

The first principle of libertarian social analysis is a concern about the concentration of power. One of the mantras of libertarianism is Lord Acton’s dictum, “Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely.” As the first selection in this section demonstrates, that concern has a long history. God’s warning to the people of Israel about “the ways of the king that will reign over you” reminded Jews and Christians for centuries that the state was at best a necessary evil.

The history of the West is characterized by competing centers of power. We may take that for granted, but it was not true everywhere. In most parts of the world, church and state were united, leaving little room for independent power centers to develop. Divided power in the West might be traced to the response of Jesus to the Pharisees: “Render unto Caesar the things that are Caesar’s and unto God the things that are God’s.” In so doing he made it clear that not all of life is under the control of the state. This radical notion took hold in Western Christianity.

The historian Ralph Raico writes, “The essence of the unique European experience is that a civilization developed that felt itself to be a whole—Christendom—and yet was radically decentralized. With the fall of Rome, . . . the continent evolved into a mosaic of separate and competing jurisdictions and polities whose internal divisions themselves excluded centralized control.” An independent church checked the power of states, just as kings prevented power from becoming centralized in the hands of the church. In the free, chartered towns of the Middle Ages, people developed the institutions of self-government. The towns provided a place for commerce to flourish.

Even law, usually thought of today as a unified product of government, has a pluralist history. As Harold Berman writes in Law and Revolution, “Perhaps the most distinctive characteristic of the Western legal tradition is the coexistence and competition within the same community of diverse jurisdictions and diverse legal systems. . . . Legal pluralism originated in the differentiation of the ecclesiastical polity from secular polities. . . . Secular law itself was divided into various competing types, including royal law, feudal law, manorial law, urban law, and mercantile law. The same person might be subject to the ecclesiastical courts in one type of case, the king’s court in another, his lord’s court in a third, the manorial court in a fourth, a town court in a fifth, a merchants’ court in a sixth.” Even more important, individuals had at least some degree of choice among courts, which encouraged all the legal systems to dispense good law.

In all these ways people in the West developed a deep skepticism about concentrated power. When kings, especially Louis XIV in France and the Stuart kings in Britain, began to claim more power than they had traditionally had, Europeans resisted. The institutions of civil society and self-government proved stronger in England than on the Continent, and the Stuarts’ attempt to impose royal absolutism ended ignominiously, with the beheading of Charles I in 1649.

Modern liberal ideas emerged as a response to absolutism, in the attempt to protect liberty from an overweening state. Especially in England, the Levellers, John Locke, and the opposition writers of the eighteenth century developed a defense of religious toleration, private property, freedom of the press, and free markets for labor and commerce.

In the following selections, Thomas Paine takes those opposition ideas a step further: Government itself is at best “a necessary evil.” The first king was no doubt just “the principal ruffian of some restless gang,” and the English monarchy itself began with a “French bastard, landing with an armed banditti.” There was no divinity in the powers that be, and the people were thus justified in rebelling against a government that exceeded its legitimate powers.

Once the American Revolution was successful, James Madison and other Americans set out on another task: creating a government on liberal principles, one that would secure the benefits of civil society and not extend itself beyond that vital but minimal task. His solution was the United States Constitution, which he defended, along with Alexander Hamilton and John Jay, in a series of newspaper essays that came to be known as The Federalist Papers, the most important American contribution to political philosophy. In the famous Federalist no. 10, he explained how the limited government of a large territory could avoid falling prey to factional influence and majoritarian excesses. If Madison and his colleagues might be viewed as conservative libertarians, many of the Anti-Federalists were more radical libertarians, who feared that the Constitution would not adequately limit the federal government and whose efforts resulted in the addition of a Bill of Rights.

Forty years after the Constitution was ratified, a young Frenchman named Alexis de Tocqueville came to America to observe the world’s first liberal country. His reflections became one of the most important works in liberal political theory, Democracy in America. He warned that a country based on political equality might develop a new kind of despotism, one that would, like a nurturing parent, “cover the surface of society with a network of small complicated rules, minute and uniform.” Americans would have to be eternally vigilant to protect their hard-won liberty.

In one of the most enduring liberal texts, On Liberty, John Stuart Mill set forth his principle that “the only purpose for which power can be rightfully exercised over any member of a civilized community, against his will, is to prevent harm to others.” (Other libertarian scholars would argue that “harm” is too vague a standard and that the better formulation would be “to protect the well-defined rights of life, liberty, and property.”) He also argued that the tasks of government should be limited—even if it might perform some task better than civil society—to avoid “the great evil of adding unnecessarily to its power.”

Twentieth-century libertarians have continued to examine the nature of power and to look for ways to limit it. H. L. Mencken excoriated government as a “hostile power” but did not hold out much hope for changing that. Isabel Paterson feared that humanitarian impulses exercised through inappropriate means could lead even good people to wield power in dangerous ways. Murray Rothbard took a radical view among libertarian scholars: that all coercive government is an illegitimate infringement on natural liberty and that all goods and services could be better supplied through voluntary processes than through government. Richard Epstein approached the issue of power differently: Given that we need some coercive government to protect us from each other and allow civil society to flourish, how do we limit it? He offers in his selection a threefold answer: federalism, separation of powers, and strict guarantees for individual rights.

Constraining power is the great challenge for any political system. Libertarians have always put that challenge at the center of their political and social analysis.

I SAMUEL 8

The Bible

The most important book in the development of Western civilization was the Bible, which of course just means “the Book” in Greek. Until recent times it was the touchstone for almost all debate on morality and government. One of its most resonant passages for the study of government was the story of God’s warning to the people of Israel when they wanted a king to rule them. Until then, as Judges 21:25 reports, “there was no king in Israel: every man did that which was right in his own eyes,” and there were judges to settle disputes. But in I Samuel, the Jews asked for a king, and God told Samuel what it would be like to have a king. This story reminded Europeans for centuries that the state was not divinely inspired. Thomas Paine, Lord Acton, and other liberals cited it frequently.

1 And it came to pass, when Samuel was old, that he made his sons judges over Israel.

2 Now the name of his firstborn was Joel; and the name of his second, Abiah: they were judges in Beersheba.

3 And his sons walked not in his ways, but turned aside after lucre, and took bribes, and perverted judgment.

4 Then all the elders of Israel gathered themselves together, and came to Samuel unto Ramah,

5 And said unto him, Behold, thou art old, and thy sons walk not in thy ways: now make us a king to judge us like all the nations.

6 But the thing displeased Samuel, when they said, Give us a king to judge us. And Samuel prayed unto the LORD.

7 And the LORD said unto Samuel, Hearken unto the voice of the people in all that they say unto thee: for they have not rejected thee, but they have rejected me, that I should not reign over them.

8 According to all the works which they have done since the day that I brought them up out of Egypt even unto this day, wherewith they have forsaken me, and served other gods, so do they also unto thee.

9 Now therefore hearken unto their voice: howbeit yet protest solemnly unto them, and shew them the manner of the king that shall reign over them.

10 And Samuel told all the words of the LORD unto the people that asked of him a king.

11 And he said, This will be the manner of the king that shall reign over you: He will take your sons, and appoint them for himself, for his chariots, and to be his horsemen; and some shall run before his chariots.

12 And he will appoint him captains over thousands, and captains over fifties; and will set them to ear his ground, and to reap his harvest, and to make his instruments of war, and instruments of his chariots.

13 And he will take your daughters to be confectionaries, and to be cooks, and to be bakers.

14 And he will take your fields, and your vineyards, and your oliveyards, even the best of them, and given them to his servants.

15 And he will take the tenth of your seed, and of your vineyards, and give to his officers, and to his servants.

16 And he will take your menservants, and your maidservants, and your goodliest young men, and your asses, and put them to his work.

17 He will take the tenth of your sheep: and ye shall be his servants.

18 And ye shall cry out in that day because of your king which ye shall have chosen you; and the LORD will not hear you in that day.

19 Nevertheless the people refused to obey the voice of Samuel; and they said, Nay; but we will have a king over us;

20 That we also may be like all the nations; and that our king may judge us, and go out before us, and fight our battles.

21 And Samuel heard all the words of the people, and he rehearsed them in the ears of the LORD.

22 And the LORD said to Samuel, Hearken unto their voice, and make them a king. And Samuel said unto the men of Israel, Go ye every man unto his city.

OF THE ORIGIN AND DESIGN OF GOVERNMENT

Thomas Paine

Thomas Paine (1737–1809) was an agitator for freedom in England, America, and France and an important theorist as well. His major works were The Rights of Man, a response to Edmund Burke’s Reflections on the Revolution in France, which is often cited as a founding document of modern conservatism, and The Age of Reason, a manifesto for what Paine regarded as rational Christianity but others denounced as atheism. This is an excerpt from his fabulously successful 1776 publication Common Sense. In this and other writings Paine helped to establish the ideology that became known first as liberalism and then as libertarianism by combining a theory of natural rights and justice with a social theory that emphasized natural harmony and spontaneous order in the absence of coercion.

Some writers have so confounded society with government, as to leave little or no distinction between them; whereas they are not only different, but have different origins. Society is produced by our wants, and government by our wickedness; the former promotes our happiness positively by uniting our affections, the latter negatively by restraining our vices. The one encourages intercourse, the other creates distinctions. The first is a patron, the last a punisher.

Society in every state is a blessing, but government even in its best state is but a necessary evil; in its worst state an intolerable one; for when we suffer, or are exposed to the same miseries by a government, which we might expect in a country without government, our calamities are heightened by reflecting that we furnish the means by which we suffer. Government, like dress, is the badge of lost innocence; the palaces of kings are built on the ruins of the bowers of paradise. For were the impulses of conscience clear, uniform, and irresistibly obeyed, man would need no other lawgiver; but that not being the case, he finds it necessary to surrender up a part of his property to furnish means for the protection of the rest; and this he is induced to do by the same prudence which in every other case advises him out of two evils to choose the least. Wherefore, security being the true design and end of government, it unanswerably follows that whatever form thereof appears most likely to ensure it to us, with the least expense and greatest benefit, is preferable to all others.

In order to gain a clear and just idea of the design and end of government, let us suppose a small number of persons settled in some sequestered part of the earth, unconnected with the rest, they will then represent the first peopling of any country, or of the world. In this state of natural liberty, society will be their first thought. A thousand motives will excite them thereto, the strength of one man is so unequal to his wants, and his mind so unfitted for perpetual solitude, that he is soon obliged to seek assistance and relief of another, who in his turn requires the same. Four or five united would be able to raise a tolerable dwelling in the midst of a wilderness, but one man might labour out the common period of life without accomplishing any thing; when he had felled his timber he could not remove it, nor erect it after it was removed; hunger in the mean time would urge him from his work, and every different want call him a different way. Disease, nay even misfortune would be death, for though neither might be mortal, yet either would disable him from living, and reduce him to a state in which he might rather be said to perish than to die.

Thus necessity, like a gravitating power, would soon form our newly arrived emigrants into society, the reciprocal blessings of which, would supersede, and render the obligations of law and government unnecessary while they remained perfectly just to each other; but as nothing but heaven is impregnable to vice, it will unavoidably happen, that in proportion as they surmount the first difficulties of emigration, which bound them together in a common cause, they will begin to relax in their duty and attachment to each other; and this remissness, will point out the necessity, of establishing some form of government to supply the defect of moral virtue.

Some convenient tree will afford them a State-House, under the branches of which, the whole colony may assemble to deliberate on public matters. It is more than probable that their first laws will have the title only of REGULATIONS, and be enforced by no other penalty than public disesteem. In this first parliament every man, by natural right will have a seat.

But as the colony increases, the public concerns will increase likewise, and the distance at which the members may be separated, will render it too inconvenient for all of them to meet on every occasion as at first, when their number was small, their habitations near, and the public concerns few and trifling. This will point out the convenience of their consenting to leave the legislative part to be managed by a select number chosen from the whole body, who are supposed to have the same concerns at stake which those have who appointed them, and who will act in the same manner as the whole body would act were they present. If the colony continue increasing, it will become necessary to augment the number of the representatives, and that the interest of every part of the colony may be attended to, it will be found best to divide the whole into convenient parts, each part sending its proper number; and that the elected might never form to themselves an interest separate from the electors, prudence will point out the propriety of having elections often; because as the elected might by that means return and mix again with the general body of the electors in a few months, their fidelity to the public will be secured by the prudent reflection of not making a rod for themselves. And as this frequent interchange will establish a common interest with every part of the community, they will mutually and naturally support each other, and on this (not on the unmeaning name of king) depends the strength of government, and the happiness of the governed.

Here then is the origin and rise of government; namely, a mode rendered necessary by the inability of moral virtue to govern the world; here too is the design and end of government, viz. freedom and security. And however our eyes may be dazzled with snow, or our ears deceived by sound; however prejudice may warp our wills, or interest darken our understanding, the simple voice of nature and of reason will say, it is right. . . .

OF MONARCHY AND HEREDITARY SUCCESSION

Mankind being originally equals in the order of creation, the equality could only be destroyed by some subsequent circumstance; the distinctions of rich, and poor, may in a great measure be accounted for, and that without having recourse to the harsh, ill-sounding names of oppression and avarice. Oppression is often the consequence, but seldom or never the means of riches; and though avarice will preserve a man from being necessitously poor, it generally makes him too timorous to be wealthy.

But there is another and greater distinction for which no truly natural or religious reason can be assigned, and that is, the distinction of men into KINGS and SUBJECTS. Male and female are the distinctions of nature, good and bad the distinctions of heaven; but how a race of men came into the world so exalted above the rest, and distinguished like some new species, is worth inquiring into, and whether they are the means of happiness or of misery to mankind.

In the early ages of the world, accord...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Introduction

- Part One: Skepticism About Power

- Part Two: Individualism and Civil Society

- Part Three: Individual Rights

- Part Four: Spontaneous Order

- Part Five: Free Markets and Voluntary Order

- Part Six: Peace and International Harmony

- Part Seven: The Libertarian Future

- The Literature of Liberty

- About the Editor

- Sources

- Copyright

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Libertarian Reader by David Boaz in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Political Philosophy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.