![]()

![]()

Act 1

THE YEAR OF

THE DRAGON

HEBEI PROVINCE, CHINA, AUGUST 1900

he sun was a furnace as young Smedley Darlington Butler and his fellow soldiers trudged across the scorched and dusty plains of northern China. There were no trees to shade them from the merciless glare. There were no cool, clean waters to relieve their terrible thirst, just the sluggish, yellow muck of the Pei Ho River, whose meandering path they wearily followed. The wagon road on which they were marching took a perversely crooked route, as all Chinese roads did, because evil spirits were said to fly on straight lines. At times the frustrated soldiers tried to shorten their march by cutting through the cornfields that lined the road. But closed in by the dense stalks where no breeze could find them, the men felt even more suffocated by the heat.

As the hours went by and the sun reached its full fury, the soldiers abandoned more and more of what they had brought. Blankets, tents, shovels, ponchos all began to litter the roadside. And then they began to strip off their very uniforms, until some were nearly naked except for the rifles and ammunition belts strung across their bodies.

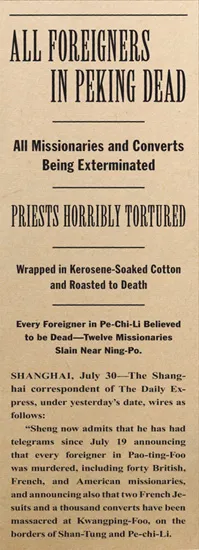

And still, they pushed on toward Peking, driven by the terror that they would be too late, that their countrymen—men, women and children—would be overrun and slaughtered by the Chinese hordes that had been laying siege to the capital city’s foreign compounds. The stories had been racing around the world for months, horrifying newspaper readers across America and Europe: stories of Christian missionaries and their families being tortured by “Oriental demons” in the most unspeakable ways—death by a thousand cuts and other exquisite agonies, described in titillating detail. Some newspapers even declared that all foreigners in Peking had already been horribly massacred. “The Streets Ran Blood,” blared the Topeka State Journal.

![]()

![]()

DAMSELS IN DISTRESS: THE ARMIES OF THE WESTERN WORLD DESCENDED ON PEKING AFTER HEARING OF OUTRAGES AGAINST “CHRISTIAN WOMEN.”

China had gone mad. The Empress Dowager, the cunning monarch who ruled the Manchu court, was reported to have unleashed a mysterious martial arts cult known as the Boxers on the “foreign devils” residing in the Middle Kingdom. Despite their humble, peasant origins, the Boxers were thought by their countrymen—including the Empress herself—to possess otherworldly powers that could withstand even the bullets and guns of the Western powers. With their long pigtails, red sashes and curved swords, the Boxers struck fear in the round-eyed missionaries and merchants who seemed to be overrunning China. But they were an inspiration to the Chinese people who felt humiliated by the Western intruders.

Now the armies of the Western world were marching on Peking, some 16,000 soldiers from eight nations. They had left the port city of Tientsin on August 4, some 97 miles away. If they were in time, this remarkable military procession would be a rescue mission. If not, they would be a blazing sword of vengeance.

Among the marching soldiers was 18-year-old U.S. Marine Corps Lieutenant Smedley Butler, who commanded a company of 45 enlisted men. Butler had already been wounded once in China, shot in the right leg during the vicious battle for Tientsin. He did not know what to expect as he and his men prepared to set off on their desperate march for Peking. He did not know if his luck would stand and whether he would ever again see his mother and father and his younger brothers, Samuel and Horace (whom he called “Horrid”). On the morning before they marched, Butler wrote his mother, Maud, a letter, using the plain language of the Quaker faith in which he was raised.

My darling Mother,

We start in one hour for Peking. Preparations all made, expect to run against 30,000 chinamen to-morrow morning. Don’t be worried about me. If I am killed, I gave my life for women and children just as dear to some poor devil as thee and Horrid are to me.

Lots of love to all. Good bye.

Thy son,

Smedley D. Butler.

Butler looked too young to die. He was a bantam rooster of a boy-man, measuring a scrappy 5-foot-9 and weighing no more than 140 pounds. His bird beak was the first thing you noticed about him, and then his penetrating eyes, which went along with his pugnacious attitude. You wouldn’t know it to look at the sinewy young man, with the massive marine tattoo carved into his chest, but he was a Philadelphia blueblood, the scion of three prominent Pennsylvania families who traced their ancestry back to William Penn’s colony. Both of his grandfathers were politically connected bankers, and his father, Thomas Butler, was a powerful congressman, who—despite the family’s devout Quaker roots—used his platform on the Naval Affairs Committee to prod turn-of-the-century America into becoming a military power.

HYSTERIA SWEPT THE AMERICAN PRESS DURING THE WARS AGAINST SPAIN AND CHINA.

Still, Congressman Butler was appalled when his teenage son announced that he was leaving the bosom of his distinguished family to join the toughest fighting arm of the military, the United States Marine Corps. But there was nothing he or the boy’s mother could do to stop him. At the time, Smedley was enrolled at prestigious Haverford School, the training ground for the sons of wealthy Quaker families. In the classroom, he was as bored and restless as young Tom Sawyer.

Maybe Smedley, with his utter disinterest in school, knew he would never equal his father in the marble halls of Washington or the plush salons of Main Line Philadelphia. So he would find another way to become a man and impress his father. He would become a man of “action, not books,” in his words.

When the USS Maine blew up in Havana Harbor in February 1898 and war fever swept through the country, that settled it. Smedley joined the crowds that built bonfires and sang out, “Remember the Maine, to Hell with Spain!” Suddenly school seemed even more “stupid and unnecessary,” he thought. At 16, Smedley announced to his mother that she must accompany him to the marine headquarters in Washington, D.C., and give permission for him to join up, or he would lie about his age and enlist anyway.

And so, after six weeks of training, Second Lieutenant Smedley Butler finally got the flashy uniform that had dazzled him when he first saw a marine officer strolling by on the streets of Philadelphia—the one with the dark-blue coat, and sky-blue trousers emblazoned with scarlet stripes down the seams. And, in July, he was shipped off to fight in Cuba—the splendid little war against the dying Spanish empire that would turn America into a young empire.

The fresh-faced marine officer arrived too late to see much action. It would not be until two years later, in a land even farther away—China, the ancient Middle Kingdom—that Smedley Butler would fully experience the savage education that is war.

When the allied forces marched out of Tientsin for Peking, to the triumphal strains of a U.S. Army band, Butler marveled at the variety of flapping banners and crisp uniforms on display—the French Zouaves in red and blue, the Royal Welsh Fusiliers with their five black ribbons hanging from their collars, the turbaned Sikhs, the Cossack cavalrymen in their white tunics and shiny black top-boots. The colorful military pageant represented the combined, fearsome might of the imperial powers: Great Britain, Germany, Austria, France, Italy, Russia, Japan and the United States. Never before had the world seen such a union of lethal force.

But as the days went by, and the sun beat down mercilessly, the procession grew ragged and dispirited. The troops choked on clouds of dust kicked up by the rumbling artillery carriages and were besieged by dark swarms of flies and bloodthirsty mosquitoes. The American soldiers were especially parched because they had brought fewer water tanks than their allies and the water sterilizing machines that Washington had promised had still not arrived.

Butler warned his men not to drink from the muddy wells they found in the villages along the way, fearing they had been poisoned by the Boxers. And the Pei Ho River looked equally putrid. But mad with thirst, Butler’s marines could not help themselves and they sometimes gulped frantically from the river, straining the sallow water with their handkerchiefs and holding their noses to block the river’s stench. To their horror, they would sometimes see headless bodies floating by—the handiwork of the Japanese soldiers leading the allied column, who not only cleared away Boxer resistance but also decapitated helpless Chinese villagers.

For the most part, the American soldiers refrained from the cruelty that seemed to come easily to their allies, especially the Japanese, Germans and Russians. Many of these soldiers felt they had the divine right of vengeance. “Spare nobody,” Kaiser Wilhelm II had commanded the German expeditionary force as they sailed from Bremerhaven. “Use your weapons so that for a thousand years hence no Chinaman will dare look askance at any German. Open the way for civilization once and for all.”

![]()

![]()

Chinese girls threw themselves down wells rather than fall into the hands of the foreign demons. The Chinese imperial soldiers and Boxers fighting desperately to block the allied advance were also terrified of being captured by the foreign invaders. When they were wounded, they would crawl into the cornfields to die, instead of being captured alive. But some were not so lucky.

Henry Savage Landor, the celebrated British writer and explorer, witnessed one particularly brutal incident on the way to Peking. Landor knew something about torture: while traveling in forbidden Tibet in 1897, he had been captured and subjected to torches and the stretching rack. But he was particularly disturbed by what he saw one day in China, when a prisoner fell into the hands of American soldiers.

“Take him away and do with him what you damned please,” an American officer told the soldiers.

The doomed man was then dragged under a railway bridge, where he was punched and kicked by the Americans, only to be replaced by a French soldier, who shot him in the face. Still breathing and moaning, the prisoner was then stomped on by a Japanese soldier. Clinging miraculously to life, he was then stripped naked by the mob of soldiers to see if he possessed any of the supernatural charms that Boxers claimed to have. “For nearly an hour, the fellow lay in this dreadful condition,” Landor recalled, “with hundreds of soldiers leaning over him to get a glimpse of his agony, and going into roars of laughter as he made ghastly contortions in his delirium.”

As Landor noted, this barbarous behavior deeply pained most of the American boys, “who were as a rule extremely humane, even at times extravagantly gracious, towards the enemy.”

Here’s how these boys left home, saying goodbye to their dearest ones, uncertain if they would ever set eyes on one another again. Here’s how they always leave home. The mothers and sisters and sweethearts gathered, ashen-faced, around them, in their barracks on the Presidio overlooking the San Francisco Bay or on Governors Island in New York Harbor, just hours before their soldier boys set sail for China. These women wanted one last embrace, heart against heart, that they could feel longer than death. But some were too frantic to keep still.

“Oh! Why did you go and enlist, Charlie? And now you have to go and leave me and the child alone,” wept one young woman. Her Charlie was with the Fifteenth U.S. Infantry, stationed at Governors Island, and a reporter overheard their agonized farewell.

“It had to be done, Lizzie,” Charlie told his young wife as she clung to his chest. “You know I could not find any work.”

And weeks later, these boys found themselves tramping through an inferno somewhere halfway around the world, in a cornfield filled with reeking corpses. They were confused about how they had ended up there, why they were killing these odd people whose language sounded like birds. And when they fell in battle, cut down by a Chinese soldier defending his homeland, Chaplain Groves would write down their name and regiment and bury the information in a sealed bottle next to the soldier. It was the only way these American boys could later be identified and sent back home to rest in eternity.

In such a wretched place, with death hovering everywhere, soldiers have only one another. They pray that their officers are decent and wise and will not get them killed. The men of First Battalion, Company A, USMC, were lucky to have Lieutenant Butler marching at the head of their column.

Despite his privileged background and tender age, Butler acted like one of them—the roughneck immig...