eBook - ePub

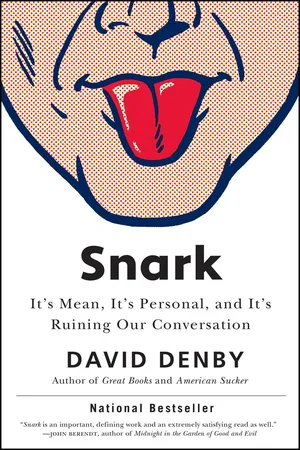

Snark

About this book

What is snark? You recognize it when you see it -- a tone of teasing, snide, undermining abuse, nasty and knowing, that is spreading like pinkeye through the media and threatening to take over how Americans converse with each other and what they can count on as true. Snark attempts to steal someone's mojo, erase her cool, annihilate her effectiveness. In this sharp and witty polemic, New Yorker critic and bestselling author David Denby takes on the snarkers, naming the nine principles of snark -- the standard techniques its practitioners use to poison their arrows. Snarkers like to think they are deploying wit, but mostly they are exposing the seethe and snarl of an unhappy country, releasing bad feeling but little laughter.

In this highly entertaining essay, Denby traces the history of snark through the ages, starting with its invention as personal insult in the drinking clubs of ancient Athens, tracking its development all the way to the age of the Internet, where it has become the sole purpose and style of many media, political, and celebrity Web sites. Snark releases the anguish of the dispossessed, envious, and frightened; it flows when a dying class of the powerful struggles to keep the barbarians outside the gates, or, alternately, when those outsiders want to take over the halls of the powerful and expel the office-holders. Snark was behind the London-based magazine Private Eye, launched amid the dying embers of the British empire in 1961; it was also central to the career-hungry, New York-based magazine Spy. It has flourished over the years in the works of everyone from the startling Roman poet Juvenal to Alexander Pope to Tom Wolfe to a million commenters snarling at other people behind handles. Thanks to the grand dame of snark, it has a prominent place twice a week on the opinion page of the New York Times.

Denby has fun snarking the snarkers, expelling the bums and promoting the true wits, but he is also making a serious point: the Internet has put snark on steroids. In politics, snark means the lowest, most insinuating and insulting side can win. For the young, a savage piece of gossip could ruin a reputation and possibly a future career. And for all of us, snark just sucks the humor out of life. Denby defends the right of any of us to be cruel, but shows us how the real pros pull it off. Snark, he says, is for the amateurs.

In this highly entertaining essay, Denby traces the history of snark through the ages, starting with its invention as personal insult in the drinking clubs of ancient Athens, tracking its development all the way to the age of the Internet, where it has become the sole purpose and style of many media, political, and celebrity Web sites. Snark releases the anguish of the dispossessed, envious, and frightened; it flows when a dying class of the powerful struggles to keep the barbarians outside the gates, or, alternately, when those outsiders want to take over the halls of the powerful and expel the office-holders. Snark was behind the London-based magazine Private Eye, launched amid the dying embers of the British empire in 1961; it was also central to the career-hungry, New York-based magazine Spy. It has flourished over the years in the works of everyone from the startling Roman poet Juvenal to Alexander Pope to Tom Wolfe to a million commenters snarling at other people behind handles. Thanks to the grand dame of snark, it has a prominent place twice a week on the opinion page of the New York Times.

Denby has fun snarking the snarkers, expelling the bums and promoting the true wits, but he is also making a serious point: the Internet has put snark on steroids. In politics, snark means the lowest, most insinuating and insulting side can win. For the young, a savage piece of gossip could ruin a reputation and possibly a future career. And for all of us, snark just sucks the humor out of life. Denby defends the right of any of us to be cruel, but shows us how the real pros pull it off. Snark, he says, is for the amateurs.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

THE FIRST FIT

The Republic of Snark

In which the author lays out the terrain of his momentous subject, defines the nature of snark, and distinguishes among high, medium, and low versions of the unfortunate practice.

This is an essay about a strain of nasty, knowing abuse spreading like pinkeye through the national conversation—a tone of snarking insult provoked and encouraged by the new hybrid world of print, television, radio, and the Internet. It’s an essay about style and also, I suppose, grace. Anyone who speaks of grace—so spiritual a word—in connection with our raucous culture risks sounding like a genteel idiot, so I had better say right away that I’m all in favor of nasty comedy, incessant profanity, trash talk, any kind of satire, and certain kinds of invective. It’s the bad kind of invective—low, teasing, snide, condescending, knowing; in brief, snark—that I hate.

Perhaps a few contrasts will make the difference clear. Jon Stewart and Stephen Colbert can be rough. Like all entertainers, they trust laughs more than anything else, and they wait for some public person to slip a stirrup and fall. “We’re carrion birds,” says Stewart, a man capable of describing Karl Rove as having a head like a lump of unbaked bread dough. But the Stewart/Colbert claws are sharpened in a special way. Even when pecking at a victim’s tender spots, they also manage to defend civic virtue four times a week. When Stephen Colbert, a liberal, wraps himself in the flag and bullies his guests in the manner of right-wing TV host Bill O’Reilly, he is practicing irony, the most powerful of all satiric weapons. Attacking the Bush administration, Colbert and Stewart were always trying to say, This is not the way a national government should behave. Snark, by contrast, has zero interest in civic virtue or anything else except the power to ridicule. When the comic Penn Jillette said on MSNBC in May 2008, that “Obama did great in February, and that’s because that was Black History Month. And now Hillary’s doing much better ’cause it’s White Bitch Month, right?” he was not, putting it mildly, practicing irony or satire. The remark was bonehead insult, but insult of a special sort. It spoke to a knowing audience—to white people irritated by black history as a celebration, and to men who assume an ambitious woman can safely be called a bitch. The layer of knowingness, in this case, was an appeal to cranky ill will and prejudice. Jillette’s joke was snark. A question I found as a comment on a right-wing blog—“Is Obama a fat-lipped nigger—or what?”—is simple racist junk. But a student named Adam LaDuca, formerly president of the Pennsylvania Federation of College Republicans, wrote on his Facebook page that Obama was “nothing more than a dumbass with a pair of lips so large he could float half of Cuba to the shores of Miami (and probably would).” That remark, in its excruciating “humor” and its layer of knowing reference, is tin-plated snark (and also racist junk).

Snark is not the same as hate speech, which is abuse directed at groups. Hate speech slashes and burns, and hopes to incite, but without much attempt at humor. Some legal scholars—most notably, Jeremy Waldron, of New York University—have argued that the United States, a tumultuous, multiethnic country with many vulnerable minorities, should consider banning hate speech by law, as some countries in Europe have done. But that is not my concern here; the legal issues lie far beyond the range of this essay, and, in any case, I am against censorship in any form, on the usual ground that it will choke legitimate critical speech as well as vicious rant. I will hunt the snark but leave hate speech alone. I will also ignore the legions of anguished, lost people on Web sites and the social networking site Facebook who are convinced that, say, Barack Obama is the Antichrist (“Buraq was the name of Muhammad’s horse!”), and who fly about wildly, like bats trapped in a country living room, looking for a way to release fear. Madness and paranoia are not the same as snark.

Nor am I talking about the elaborately sadistic young sports known on the Internet as “trolls.” These are technically enabled young men, part hackers, part stalkers, who pull such pranks as teasing the parents of a child who has committed suicide or sending flashing lights onto a Web site for epileptics. The lights may cause seizures. Fun! The trolls have a merry time screwing people up. What they do violates existing statutes, * and if federal and state authorities had the energy and resources to pursue them, the trolls could probably be prosecuted for harassment. So far they have gone largely unpunished, but I leave them to the cops and prosecutors. Finally, I will bypass the issue of political correctness, which, rightly or wrongly, is a way of protecting groups against calumny and lesser slights. Political correctness actually shares one leading characteristic with snark—it refuses true political engagement, the job of getting at the truth of things. All too often, PC tries to rein in humor that might brush against a truth. What I’m doing here—hunting the snark—is a way of preserving humor. Those of us who are against snark want to humble the lame, the snide, and the lazy—and promote the true wits.

Snark attacks individuals, not groups, though it may appeal to a group mentality, depositing a little bit more toxin into already poisoned waters. Snark is a teasing, rug-pulling form of insult that attempts to steal someone’s mojo, erase her cool, annihilate her effectiveness, and it appeals to a knowing audience that shares the contempt of the snarker and therefore understands whatever references he makes. It’s all jeer and josh, a form of bullying that, except at its highest levels, beggars the soul of humor. In the 2000 presidential campaign, Maureen Dowd of the New York Times had Al Gore “so feminized and diversified and ecologically correct, he’s practically lactating” in one column and buffing his pecs and ridging his abs in another column. Which was it? Effeminate or macho? Snark will get you any way it can, fore and aft, and to hell with consistency. In a media society, snark is an easy way of seeming smart. When Harvard professor Samantha Power resigned from Obama’s campaign on March 7, 2008, after calling Hillary Clinton “a monster,” Michael Goldfarb’s comment, on the blog of the conservative magazine the Weekly Standard, was “Tell us something we don’t know.” Power’s remark is a plain insult; Goldfarb’s, with its cozy “we,” which adds a twist of in-group knowingness, is snark. Snark doesn’t create a new image, a new idea. It’s parasitic, referential, insinuating.

Of course, snark is just words, and if you look at it one piece at a time, it seems of piddling importance. But it’s annoying as hell, the most dreadful style going, and ultimately debilitating. A future America in which too many people sound mean and silly, like small yapping dogs tied to a post; in which we insult one another merrily in a kind of endless zany brouhaha; in which the lowest, most insinuating and insulting side threatens to win national political campaigns—this America will leave everyone, including the snarkers, in a foul mood once the laughs die out. At the moment, there are snarky vice presidential campaigns (Sarah Palin’s mean-girl assault on Barack Obama as “someone who sees America as imperfect enough to pal around with terrorists who targeted their own country…This is not a man who sees America like you and I see America.”); snark-influenced crafts (advertising); an enormous, commercially flourishing snark industry (celebrity culture); snarky news-and-commentary cable TV shows, left and right; and snark words, such as whiny and whiner, which are often used to cut the ground under anyone with a legitimate complaint. Senator John McCain, displaying some creative flair in his attacks on Barack Obama on October 15, 2008, added a snarky visual effect (perhaps a first in a presidential debate) to ordinary sarcasm, by holding up his fingers for air quotes around the word health in a discussion on abortion: “Here again is the eloquence of Senator Obama—the ‘health’ of the mother. You know, that’s been stretched by the pro-abortion movement in America to mean almost anything.” By using air quotes (was he channeling the late Chris Farley?), McCain was sending a sportive signal to pro-lifers—that’s the snarky part—but also suggesting, perhaps unconsciously, that the heath of the mother was somehow irrelevant to the matter of abortion. At the end of the first decade of the twenty-first century, snark sounds like the seethe and snarl of an unhappy and ferociously divided country, a country releasing its resentment in rancid jokes. It’s a verbal bridge to nowhere. I’ve been accused of writing some myself.*

The practice has often been mislabeled. Snark is not the same thing, for instance, as irreverence or spoof. I’ve heard the morally outraged satirist Lenny Bruce described as a pioneer of snark, which is absurd. Bruce, in his way, was as serious as the prophet Jeremiah. David Letterman the ironist is snarky; Jay Leno, a straight joke teller, is not. Don Rickles takes on hecklers and insults his audience, but his act is a formal structure whose unvarying rules are known in advance. If he weren’t vicious, people wouldn’t go to hear him. What he does isn’t snark; it’s a harmless, self-contained ritual performed by a cobra with a ribbon tied around its head.

The platonic ideal of snark is something like this: Two girls are sitting in a high school cafeteria putting down a third, who’s sitting on the other side of the room. What’s peculiar about this event is that the girl on the other side of the room is their best friend. In that scenario, snark is abusive or sarcastic speech that operates like poisoned arrows within a closed space. Its intention is to offer solidarity between two or more parties and to exclude someone from the same group. On Gossip Girl, this is juicily entertaining, but in real life it’s as hostile as spit. The crab that tries to escape the barrel—the girl who dresses differently or studies harder—gets pulled back into the barrel. Who does she think she is? A young writer who creates an ambitious work of fiction gets snarked by journalists of lesser ambition. What a pretentious phony! Snark often functions as an enforcer of mediocrity and conformity. In its cozy knowingness, snark flatters you by assuming that you get the contemptuous joke. You’ve been admitted, or readmitted, to a club, though it may be the club of the second-rate.

Let’s not fall into a misunderstanding. Life would be intolerable without any snark at all. There are public events like Dick Cheney’s shooting his close friend in the puss, or Eliot Spitzer’s encounters with a $4,300 hooker after prosecuting vice for several years—events that no human being could fail to relish, rehash, retell. These misadventures inspired snarky comments by the hundreds, and all one can say about the comments is that malice is as natural as kindness, and that someone completely without snarky impulses would have little humor of any sort. One can’t, without hypocrisy, be against all snark all the time. The practice exists at different levels of ambition and skill, and at the top levels snark crosses into wit. In a 1976 essay (“Some Memories of the Glorious Bird and an Earlier Self”), Gore Vidal, a master of high snark, recounts the early days of his friendship with Tennessee Williams. Eventually, the narrative turns to Truman Capote:

Capote would keep us entranced with mischievous fantasies about the great. Apparently, the very sight of him was enough to cause lifelong heterosexual men to tumble out of unsuspected closets. When Capote refused to surrender his virtue to the drunken Errol Flynn, “Errol threw all my suitcases out of the window of the Beverly Wilshire Hotel!” I should note here that the young Capote was no less attractive in his person then than he is today.

This is funny no matter how you read it. But the last line achieves its full snarky glory only if you know that in 1976, when Vidal wrote these sentences, Capote was a sodden mess. Vidal’s insult is perfectly phrased. How could one be against it? A writer like the Roman poet Juvenal (discussed in the Second Fit), who deploys a virulent, sometimes obscene wit—an early case of snark, I think—can make proper writers seem timid and slow.

Another, more complicated example of contemporary high snark—or, rather, attempted high snark: The literary editor and critic Leon Wieseltier reviewed The Second Plane, a collection of essays about Islamic extremism by the English writer Martin Amis, in the New York Times of April 27, 2008, and, at great length, Wieseltier deplored Amis’s lack of seriousness. Amis, he wrote, used the catastrophe of 9/11 to show off his brilliant phrasemaking; instead, he should have tried—more soberly and with better information—to understand the nature of radical Islam. Wieseltier’s clinching judgment goes like this: “Pity the writer who wants to be Bellow but is only Mailer.” Now, this is a knowing signal to readers who believe that Saul Bellow was a greater writer than Norman Mailer. Yet it’s an odd insult, since most of us would hardly turn scarlet with shame if Mailer’s The Armies of the Night or The Executioner’s Song suddenly turned up on our résumé. What is there to “pity”? In that respect, Wieseltier’s remark is a misfire. In another respect, it’s a stealth dart aimed directly at Martin Amis’s heart. An even smaller group of readers would know that Amis adores Bellow’s work and dislikes Mailer’s. The snark is unspoken: You write like someone you despise, not like your hero.

At the more popular level, there is a fine piece of wickedness perfected by the British humor magazine Private Eye. In the sixties, a British woman journalist, disappearing from a London party, had a pleasing encounter with a former cabinet minister in the government of Ugandan dictator Milton Obote; afterward, reappearing, she said that the two were “upstairs discussing Uganda.” Thereafter, and for decades, whenever any public figure was taunted by the magazine for illicit sex, he or she was described as having “Ugandan discussions.” The British libel laws are tougher than ours; the Uganda euphemism (and there were others) began as a way of avoiding libel, but it became a snazzy repeated joke, an insult that gathered laughter around it every time it was applied to a new victim. The two hundred thousand or so readers of Private Eye gloried in a gag that united them within the walls of an exclusively knowing club. “Ugandan discussions,” a terrific piece of mid-snark, is much funnier than anything appearing in America today.

At what point do we write snark out of the book of life—or at least out of the book of style? When it lacks imagination, freshness, fantasy, verbal invention and adroitness—all the elements of wit. When it’s just mean, low, ragging insult with a little curlicue of knowingness. Much of what passes for humor in American public discourse strikes me this way, and, in the Fourth Fit, I will set out the way snark is written today—a kind of stylebook of snark—and give examples. If you crave immediate proof, turn to the discussion threads that follow a routine post on so many Web sites. For every bright and easy conversation, there’s another one that turns into a free-fire zone of bilious, snarling, resentful, other-annihilating rage, complete with such savories as racist taunt, nationalist war whoops (“Fuck those towel-heads”), misogynist rant, gay-baiting witticisms. In these effusions, snark is the preferred mode of attack. Everyone, it seems, wants to be a comic. I would bet that half the words written as instant messages or Twitter are snark of one sort or another. As for commenters, they don’t just address the famous and powerful; they light into one another. You can’t miss them if you look, and even a man as generous as Walt Whitman would be hard-pressed to hear in these flares the barbaric yawp of a free people. Then there are the college men writing on such sites as Juicy Campus who have slept with a woman and then refer to her as “a whore” by name while hidin...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Colophon

- ALSO BY DAVID DENBY

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- Author's Note

- Contents

- The First Fit: The Republic of Snark

- Reference List

- Acknowledgments

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Snark by David Denby in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Popular Culture. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.