- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

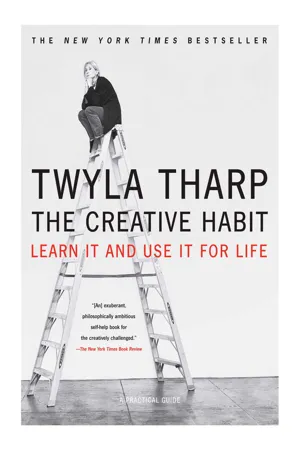

One of the world’s leading creative artists, choreographers, and creator of the smash-hit Broadway show, Movin’ Out, shares her secrets for developing and honing your creative talents—at once prescriptive and inspirational, a book to stand alongside The Artist’s Way and Bird by Bird.

All it takes to make creativity a part of your life is the willingness to make it a habit. It is the product of preparation and effort, and it is within reach of everyone. Whether you are a painter, musician, businessperson, or simply an individual yearning to put your creativity to use, The Creative Habit provides you with thirty-two practical exercises based on the lessons Twyla Tharp has learned in her remarkable thirty-five-year career.

In “Where's Your Pencil?” Tharp reminds you to observe the world—and get it down on paper. In “Coins and Chaos,” she gives you an easy way to restore order and peace. In “Do a Verb,” she turns your mind and body into coworkers. In “Build a Bridge to the Next Day,” she shows you how to clean the clutter from your mind overnight.

Tharp leads you through the painful first steps of scratching for ideas, finding the spine of your work, and getting out of ruts and into productive grooves. The wide-open realm of possibilities can be energizing, and Twyla Tharp explains how to take a deep breath and begin.

All it takes to make creativity a part of your life is the willingness to make it a habit. It is the product of preparation and effort, and it is within reach of everyone. Whether you are a painter, musician, businessperson, or simply an individual yearning to put your creativity to use, The Creative Habit provides you with thirty-two practical exercises based on the lessons Twyla Tharp has learned in her remarkable thirty-five-year career.

In “Where's Your Pencil?” Tharp reminds you to observe the world—and get it down on paper. In “Coins and Chaos,” she gives you an easy way to restore order and peace. In “Do a Verb,” she turns your mind and body into coworkers. In “Build a Bridge to the Next Day,” she shows you how to clean the clutter from your mind overnight.

Tharp leads you through the painful first steps of scratching for ideas, finding the spine of your work, and getting out of ruts and into productive grooves. The wide-open realm of possibilities can be energizing, and Twyla Tharp explains how to take a deep breath and begin.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Creative Habit by Twyla Tharp in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Personal Development & Creativity. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Personal DevelopmentSubtopic

CreativityChapter 1

I walk into a white room

I walk into a large white room. It’s a dance studio in midtown Manhattan. I’m wearing a sweatshirt, faded jeans, and Nike cross-trainers. The room is lined with eight-foot-high mirrors. There’s a boom box in the corner. The floor is clean, virtually spotless if you don’t count the thousands of skid marks and footprints left there by dancers rehearsing. Other than the mirrors, the boom box, the skid marks, and me, the room is empty.

In five weeks I’m flying to Los Angeles with a troupe of six dancers to perform a dance program for eight consecutive evenings in front of twelve hundred people every night. It’s my troupe. I’m the choreographer. I have half of the program in hand—a fifty-minute ballet for all six dancers set to Beethoven’s twenty-ninth piano sonata, the “Hammerklavier.” I created the piece more than a year ago on many of these same dancers, and I’ve spent the past few weeks rehearsing it with the company.

The other half of the program is a mystery. I don’t know what music I’ll be using. I don’t know which dancers I’ll be working with. I have no idea what the costumes will look like, or the lighting, or who will be performing the music. I have no idea of the length of the piece, although it has to be long enough to fill the second half of a full program to give the paying audience its money’s worth.

The length of the piece will dictate how much rehearsal time I need. This, in turn, means getting on the phone to dancers, scheduling studio time, and getting the ball rolling—all on the premise that something wonderful will come out of what I fashion in the next few weeks in this empty white room.

My dancers expect me to deliver because my choreography represents their livelihood. The presenters in Los Angeles expect the same because they’ve sold a lot of tickets to people with the promise that they’ll see something new and interesting from me. The theater owner (without really thinking about it) expects it as well; if I don’t show up, his theater will be empty for a week. That’s a lot of people, many of whom I’ve never met, counting on me to be creative.

But right now I’m not thinking about any of this. I’m in a room with the obligation to create a major dance piece. The dancers will be here in a few minutes. What are we going to do?

To some people, this empty room symbolizes something profound, mysterious, and terrifying: the task of starting with nothing and working your way toward creating something whole and beautiful and satisfying. It’s no different for a writer rolling a fresh sheet of paper into his typewriter (or more likely firing up the blank screen on his computer), or a painter confronting a virginal canvas, a sculptor staring at a raw chunk of stone, a composer at the piano with his fingers hovering just above the keys. Some people find this moment—the moment before creativity begins—so painful that they simply cannot deal with it. They get up and walk away from the computer, the canvas, the keyboard; they take a nap or go shopping or fix lunch or do chores around the house. They procrastinate. In its most extreme form, this terror totally paralyzes people.

The blank space can be humbling. But I’ve faced it my whole professional life. It’s my job. It’s also my calling. Bottom line: Filling this empty space constitutes my identity.

I’m a dancer and choreographer. Over the last 35 years, I’ve created 130 dances and ballets. Some of them are good, some less good (that’s an understatement—some were public humiliations). I’ve worked with dancers in almost every space and environment you can imagine. I’ve rehearsed in cow pastures. I’ve rehearsed in hundreds of studios, some luxurious in their austerity and expansiveness, others filthy and gritty, with rodents literally racing around the edges of the room. I’ve spent eight months on a film set in Prague, choreographing the dances and directing the opera sequences for Milos Forman’s Amadeus. I’ve staged sequences for horses in New York City’s Central Park for the film Hair. I’ve worked with dancers in the opera houses of London, Paris, Stockholm, Sydney, and Berlin. I’ve run my own company for three decades. I’ve created and directed a hit show on Broadway. I’ve worked long enough and produced with sufficient consistency that by now I find not only challenge and trepidation but peace as well as promise in the empty white room. It has become my home.

After so many years, I’ve learned that being creative is a full-time job with its own daily patterns. That’s why writers, for example, like to establish routines for themselves. The most productive ones get started early in the morning, when the world is quiet, the phones aren’t ringing, and their minds are rested, alert, and not yet polluted by other people’s words. They might set a goal for themselves—write fifteen hundred words, or stay at their desk until noon—but the real secret is that they do this every day. In other words, they are disciplined. Over time, as the daily routines become second nature, discipline morphs into habit.

It’s the same for any creative individual, whether it’s a painter finding his way each morning to the easel, or a medical researcher returning daily to the laboratory. The routine is as much a part of the creative process as the lightning bolt of inspiration, maybe more. And this routine is available to everyone.

Creativity is not just for artists. It’s for businesspeople looking for a new way to close a sale; it’s for engineers trying to solve a problem; it’s for parents who want their children to see the world in more than one way. Over the past four decades, I have been engaged in one creative pursuit or another every day, in both my professional and my personal life. I’ve thought a great deal about what it means to be creative, and how to go about it efficiently. I’ve also learned from the painful experience of going about it in the worst possible way. I’ll tell you about both. And I’ll give you exercises that will challenge some of your creative assumptions—to make you stretch, get stronger, last longer. After all, you stretch before you jog, you loosen up before you work out, you practice before you play. It’s no different for your mind.

I will keep stressing the point about creativity being augmented by routine and habit. Get used to it. In these pages a philosophical tug of war will periodically rear its head. It is the perennial debate, born in the Romantic era, between the beliefs that all creative acts are born of (a) some transcendent, inexplicable Dionysian act of inspiration, a kiss from God on your brow that allows you to give the world The Magic Flute, or (b) hard work.

If it isn’t obvious already, I come down on the side of hard work. That’s why this book is called The Creative Habit. Creativity is a habit, and the best creativity is a result of good work habits. That’s it in a nutshell.

The film Amadeus (and the play by Peter Shaffer on which it’s based) dramatizes and romanticizes the divine origins of creative genius. Antonio Salieri, representing the talented hack, is cursed to live in the time of Mozart, the gifted and undisciplined genius who writes as though touched by the hand of God. Salieri recognizes the depth of Mozart’s genius, and is tortured that God has chosen someone so unworthy to be His divine creative vessel.

Of course, this is hogwash. There are no “natural” geniuses. Mozart was his father’s son. Leopold Mozart had gone through an arduous education, not just in music, but also in philosophy and religion; he was a sophisticated, broad-thinking man, famous throughout Europe as a composer and pedagogue. This is not news to music lovers. Leopold had a massive influence on his young son. I question how much of a “natural” this young boy was. Genetically, of course, he was probably more inclined to write music than, say, play basketball, since he was only three feet tall when he captured the public’s attention. But his first good fortune was to have a father who was a composer and a virtuoso on the violin, who could approach keyboard instruments with skill, and who upon recognizing some ability in his son, said to himself, “This is interesting. He likes music. Let’s see how far we can take this.”

Leopold taught the young Wolfgang everything about music, including counterpoint and harmony. He saw to it that the boy was exposed to everyone in Europe who was writing good music or could be of use in Wolfgang’s musical development. Destiny, quite often, is a determined parent. Mozart was hardly some naive prodigy who sat down at the keyboard and, with God whispering in his ears, let the music flow from his fingertips. It’s a nice image for selling tickets to movies, but whether or not God has kissed your brow, you still have to work. Without learning and preparation, you won’t know how to harness the power of that kiss.

Nobody worked harder than Mozart. By the time he was twenty-eight years old, his hands were deformed because of all the hours he had spent practicing, performing, and gripping a quill pen to compose. That’s the missing element in the popular portrait of Mozart. Certainly, he had a gift that set him apart from others. He was the most complete musician imaginable, one who wrote for all instruments in all combinations, and no one has written greater music for the human voice. Still, few people, even those hugely gifted, are capable of the application and focus that Mozart displayed throughout his short life. As Mozart himself wrote to a friend, “People err who think my art comes easily to me. I assure you, dear friend, nobody has devoted so much time and thought to composition as I. There is not a famous master whose music I have not industriously studied through many times.” Mozart’s focus was fierce; it had to be for him to deliver the music he did in his relatively short life, under the conditions he endured, writing in coaches and delivering scores just before the curtain went up, dealing with the distractions of raising a family and the constant need for money. Whatever scope and grandeur you attach to Mozart’s musical gift, his so-called genius, his discipline and work ethic were its equal.

I’m sure this is what Leopold Mozart saw so early in his son who, as a three-year-old, one day impulsively jumped up on the stool to play his older sister’s harpsichord—and was immediately smitten. Music quickly became Mozart’s passion, his preferred activity. I seriously doubt that Leopold had to tell his son for very long, “Get in there and practice your music.” The child did it on his own.

More than anything, this book is about preparation: In order to be creative you have to know how to prepare to be creative.

No one can give you your subject matter, your creative content; if they could, it would be their creation and not yours. But there’s a process that generates creativity—and you can learn it. And you can make it habitual.

There’s a paradox in the notion that creativity should be a habit. We think of creativity as a way of keeping everything fresh and new, while habit implies routine and repetition. That paradox intrigues me because it occupies the place where creativity and skill rub up against each other.

It takes skill to bring something you’ve imagined into the world: to use words to create believable lives, to select the colors and textures of paint to represent a haystack at sunset, to combine ingredients to make a flavorful dish. No one is born with that skill. It is developed through exercise, through repetition, through a blend of learning and reflection that’s both painstaking and rewarding. And it takes time. Even Mozart, with all his innate gifts, his passion for music, and his father’s devoted tutelage, needed to get twenty-four youthful symphonies under his belt before he composed something enduring with number twenty-five. If art is the bridge between what you see in your mind and what the world sees, then skill is how you build that bridge.

That’s the reason for the exercises. They will help you develop skill. Some might seem simple. Do them anyway—you can never spend enough time on the basics. Before he could write Così fan tutte, Mozart had practiced his scales.

While modern dance and ballet are my métier, they are not the subject of this book. I promise you that the text will not be littered with dance jargon. You will not be confused by first positions and pliés and tendus in these pages. I will assume that you’re a reasonably sophisticated and open-minded person. I hope you’ve been to the ballet and seen a dance company in action on stage. If you haven’t, shame on you; that’s like admitting you’ve never read a novel or strolled through a museum or heard a Beethoven symphony live. If you give me that much, we can work together.

The way I figure it, my work habits are applicable to everyone. You’ll find that I’m a stickler about preparation. My daily routines are transactional. Everything that happens in my day is a transaction between the external world and my internal world. Everything is raw material. Everything is relevant. Everything is usable. Everything feeds into my creativity. But without proper preparation, I cannot see it, retain it, and use it. Without the time and effort invested in getting ready to create, you can be hit by the thunderbolt and it’ll just leave you stunned.

Take, for example, a wonderful scene in the film The Karate Kid. The teenaged Daniel asks the wise and wily Mr. Miyagi to teach him karate. The old man agrees and orders Daniel first to wax his car in precisely opposed circular motions (“Wax on, wax off”). Then he tells Daniel to paint his wooden fence in precise up and down motions. Finally, he makes Daniel hammer nails to repair a wall. Daniel is puzzled at first, then angry. He wants to learn the martial arts so he can defend himself. Instead he is confined to household chores. When Daniel is finished restoring Miyagi’s car, fence, and walls, he explodes with rage at his “mentor.” Miyagi physically attacks Daniel, who without thought or hesitation defends himself with the core thrusts and parries of karate. Through Miyagi’s deceptively simple chores, Daniel has absorbed the basics of karate—without knowing it.

In the same spirit as Miyagi teaches karate, I hope this book will help you be more creative. I can’t guarantee that everything you’ll create will be wonderful—that’s up to you—but I do promise that if you read through the book and heed even half the suggestions, you’ll never be afraid of a blank page or an empty canvas or a white room again. Creativity will become your habit.

Chapter 2

rituals of preparation

I begin each day of my life with a ritual: I wake up at 5:30 A.M., put on my workout clothes, my leg warmers, my sweatshirts, and my hat. I walk outside my Manhattan home, hail a taxi, and tell the driver to take me to the Pumping Iron gym at 91st Street and First Avenue, where I work out for two hours. The ritual is not the stretching and weight training I put my body through each morning at the gym; the ritual is the cab. The moment I tell the driver where to go I have completed the ritual.

It’s a simple act, but doing it the same way each morning habitualizes it—makes it repeatable, easy to do. It reduces the chance that I would skip it or do it differently. It is one more item in my arsenal of routines, and one less thing to think about.

Some people might say that simply stumbling out of bed and getting into a taxicab hardly rates the honorific “ritual.” It glorifies a mundane act that anyone can perform.

I disagree. First steps are hard; it’s no one’s idea of fun to wake up in the dark every day and haul one’s tired body to the gym. Like everyone, I have days when I wake up, stare at the ceiling, and ask myself, Gee, do I feel like working out today? But the quasi-religious power I attach to this ritual keeps me from rolling over and going back to sleep.

It’s vital to establish some rituals—automatic but decisive patterns of behavior—at the beginning of the creative process, when you are most at peril of turning back, chickening out, giving up, or going the wrong way.

A ritual, the Oxford English Dictionary tells me, is “a prescribed order of performing religious or other devotional service.” All that applies to my morning ritual. Thinking of it as a ritual has a transforming effect on the activity.

Turning something into a r...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- Chapter 1: I Walk into a White Room

- Chapter 2: Rituals of Preparation

- Chapter 3: Your Creative DNA

- Chapter 4: Harness Your Memory

- Chapter 5: Before You Can Think out of the Box, You Have to Start with a Box

- Chapter 6: Scratching

- Chapter 7: Accidents Will Happen

- Chapter 8: Spine

- Chapter 9: Skill

- Chapter 10: Ruts and Grooves

- Chapter 11: An “A” in Failure

- Chapter 12: The Long Run

- Acknowledgments

- About the Author

- Copyright