- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The Essential Guide to the Cameraman's Craft

Since its initial publication in 1973, Cinematography has become the guidebook for filmmakers. Based on their combined fifty years in the film and television industry, authors Kris Malkiewicz and M. David Mullen lay clear and concise groundwork for basic film techniques, focusing squarely on the cameraman's craft. Readers will then learn step-by-step how to master more advanced techniques in postproduction, digital editing, and overall film production.

This completely revised third edition, with more than 200 new illustrations, will provide a detailed look at:

Whether the final product is a major motion picture, an independent film, or simply a home video, Cinematography can help any filmmaker translate his or her vision into a quality film.

Since its initial publication in 1973, Cinematography has become the guidebook for filmmakers. Based on their combined fifty years in the film and television industry, authors Kris Malkiewicz and M. David Mullen lay clear and concise groundwork for basic film techniques, focusing squarely on the cameraman's craft. Readers will then learn step-by-step how to master more advanced techniques in postproduction, digital editing, and overall film production.

This completely revised third edition, with more than 200 new illustrations, will provide a detailed look at:

- How expert camera operation can produce consistent, high-quality results

- How to choose film stocks for the appearance and style of the finished film

- How to measure light in studio and location shooting for the desired appearance

- How to coordinate visual and audio elements to produce high-quality sound tracks

Whether the final product is a major motion picture, an independent film, or simply a home video, Cinematography can help any filmmaker translate his or her vision into a quality film.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

CAMERAS

The cinematographer’s most basic tool is the motion picture camera. This piece of precision machinery comprises scores of coordinated functions, each of which demands understanding and care if the camera is to produce the best and most consistent results. The beginning cinematographer’s goal should be to become thoroughly familiar and comfortable with the camera’s operation, so that he or she can concentrate on the more creative aspects of cinematography.

This chapter covers many isolated bits of practical information. However, once you become familiar with camera operation, you will be able to move on to the substance of the cinematographer’s craft in subsequent chapters. In the meantime, you are well advised to try to absorb each operation-oriented detail presented in this chapter, because operating a camera is all details. If any detail is neglected, the quality of the work may be impaired.

PRINCIPLE OF INTERMITTENT MOVEMENT

The film movement mechanism is what really distinguishes a cinema camera from a still camera. The illusion of image motion is created by a rapid succession of still photographs. To arrest every frame for the time of exposure, the principle of an intermittent mechanism was borrowed from clocks and sewing machines. Almost all general-purpose motion picture cameras employ the intermittent principle.

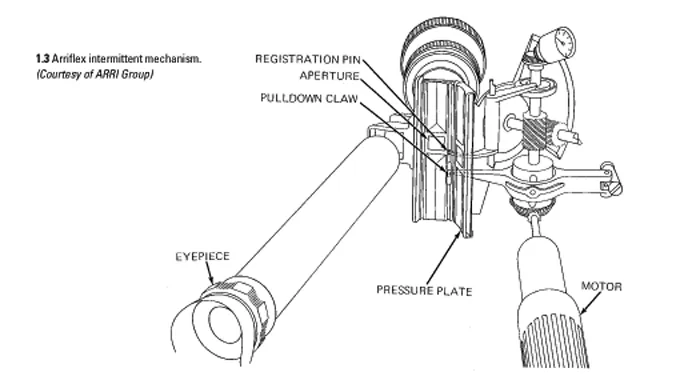

Intermittent mechanisms vary in design. All have a pull-down claw and pressure plate. Some have a registration pin as well. The pull-down claw engages the film perforation and moves the film down one frame. It then disengages and goes back up to pull down the next frame. While the claw is disengaged, the pressure plate holds the film steady for the period of exposure. Some cameras have a registration pin that enters the film perforation for extra steadiness while the exposure is made.

Whatever mechanism is employed requires the best materials and machining possible, which is one reason good cameras are expensive. The film gate (the part of the camera where the pressure plate, pull-down claw, and registration pin engage the film) needs a good deal of attention during cleaning and threading. The film gate is never too clean. This is the area where the exposure takes place, so any particles of dirt or hair will show on the exposed film and perhaps scratch it. In addition to miscellaneous debris such as sand, hair, and dust, sometimes a small amount of emulsion comes off the passing film and collects in the gate. It must be removed. This point is essential. On feature films, some camera assistants clean the gate after every shot. They know that one grain of sand or bit of emulsion can ruin a day’s work.

The gate should first be cleaned with a rubber-bulb syringe or compressed air to blow foreign particles away. Cans of compressed air must be used in an upright position; otherwise they will spray a gluey substance into the camera. When blowing out the aperture, it is recommended that you spray from the open lens port side, with the mirror shutter cleared out of the way, through the aperture, rather than from inside the threading area into the aperture. This helps prevent blowing particles into the mirror area. An orangewood stick, available wherever cosmetics are sold, can then be used to remove any sticky emulsion buildup. There is also an ARRI plastic “skewer” for this job, bent at the end to allow you to get the inner edges of the aperture better. The gate and pressure plate should also be wiped with a clean chamois cloth—never with linen. Never use metal tools for cleaning the gate, or, for that matter, for cleaning any part of the film movement mechanism, because these may cause abrasions that in turn will scratch the passing film. Do not use Q-tips either, as these will leave lint behind.

The gate should be cleaned every time the camera is reloaded. At the same time, the surrounding camera interior and magazine should also be cleaned to ensure that no dirt will find its way to the gate while the camera is running.

The intermittent movement requires the film to be slack so that as it alternately stops and jerks ahead in one-frame advances, there will be no strain on it. Therefore, one or two sprocket rollers are provided to maintain two loops, one before and one after the gate. In some cameras (such as the Bolex and Canon Scoopic), a self-threading mechanism forms the loops automatically. In Super-8 cassettes and cartridges, the loops are already formed by the manufacturer. On manually threaded cameras, the film path showing loop size is usually marked.

Too small a loop will not absorb the jerks of the intermittent movement, resulting in picture unsteadiness, scratched film, broken perforations, and possibly a camera jam. An oversize loop may vibrate against the camera interior and also cause an unsteady picture and scratched film. Either too large or too small a loop will also contribute to camera noise.

Camera Speeds

The speed at which the intermittent movement advances the film is expressed in frames per second (fps). Each frame exposed is a single sample of a moving subject, so the higher the sampling rate, that is, the faster the frame rate, the smoother the motion will be reproduced. To reproduce movement on the screen faithfully, the film must be projected at the same speed as it was shot. Standard shooting and projection speed for 16mm and 35mm is 24 fps; standard speeds for 8mm and Super-8 are 24 fps for sound and 18 fps (or 24 fps) for silent.

If both the camera and the projector are run at the same speeds, say 24 fps, then the action will be faithfully reproduced. However, if the camera runs slower than the projector, the action will appear to move faster on the screen than it did in real life. For example, an action takes place in four seconds (real time) and it is photographed at 12 fps. That means that the four seconds of action is recorded over forty-eight frames. If it is now projected at standard sound speed of 24 fps, it will take only two seconds to project. Therefore, the action that took four seconds in real life is sped up to two seconds on the screen because the camera ran slower than the projector.

The opposite is also true. If the camera runs faster than the projector, the action will be slowed down in projection. So to obtain slow motion, speed the camera up; to obtain fast motion, slow the camera down.

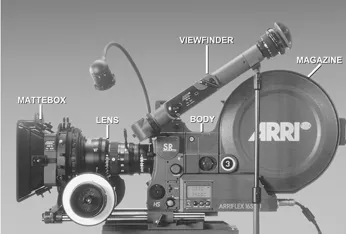

1.1 Arriflex SR3 camera. (Courtesy of ARRI Group)

1.2 Arriflex camera gate.

1.3 Arriflex intermittent mechanism. (Courtesy of ARRI Group)

This variable speed principle has several applications. Time-lapse photography can compress time and make very slow movement visible, such as the growth of a flower or the movement of clouds across the sky. Photographing slow-moving clouds at a rate of, say, one frame every three seconds will make them appear to be rushing through the screen when the film is projected at 24 fps. On the other hand, movements filmed at 36 fps or faster acquire a slow, dreamy quality at 24 fps on the screen. Such effects can be used to create a mood or analyze a movement. A very practical use of slow motion is to smooth out a jerky camera movement such as a rough traveling shot. The jolts are less prominent in slow motion.

To protect the intermittent movement, never run the camera at high speeds when it is not loaded.

When sound movies arrived in 1927, 24 fps was firmly established as the standard shooting and projection rate, although it was a frame rate occasionally used by Silent Era filmmakers. It is not actually the ideal frame rate for the recreation of motion, as it provides barely enough individual motion samples over time to create the sensation of smooth, continuous motion when played back. However, it’s become the frame rate that audiences are most accustomed to seeing in movies and has become an integral part of the “film look” that many people discuss these days as they attempt to get video technology to emulate film. The main artifacts to this fairly low frame rate are strobing and flicker. Strobing is the effect of sensing that the motion is made up of too few samples and therefore does not feel continuous. One of the ramifications is that it is sometimes necessary to minimize fast movement, such as when panning the camera across a landscape; otherwise the motion seems too staccato, too jumpy. Flicker happens when the series of still images are not being flashed quickly enough for the viewer to perceive the light and image as being continuously “on.” The solution generally has been for film projectors to use a twin-bladed shutter to double the number of times the same film frame is flashed before the next frame is shown. So even if the movie was shot and then projected at 24 fps, the viewer is seeing forty-eight flashes per second on the screen.

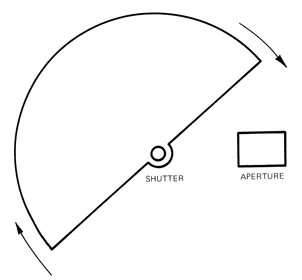

SHUTTER

A change in camera speed will cause a change in shutter speed. In most cameras the shutter consists of a rotating disk with a 180°cutout (a half circle). As the disk rotates it closes over the aperture, stopping exposure and allowing the movement to advance the film to the next frame. Rotating further, the cutout portion allows the new frame to be exposed and then covers it again for the next pull-down. The shutter rotates constantly, and therefore the film is exposed half the time and covered the other half. So when the camera is running at 24 fps, the actual period of exposure for each frame is 1÷48 second (half of 1÷24). Varying the speed of the camera also changes the exposure time. For example, by slowing the movement by half, or to 12 fps, we increase the exposure period for each frame, from 1÷48 to 1÷24 second. Similarly, by speeding up the movement, doubling it from the normal 24 fps to 48 fps, we reduce the exposure period from 1÷48 to 1÷96 second. Knowing these relationships, we can adjust the f-stop to compensate for the change in exposure time when filming fast or slow motion.

A change in the speed of film movement can be useful when filming at low light levels. For example, suppose you are filming a cityscape at dusk and there is not enough light. By reducing your speed to 12 fps, you can double the exposure period for each frame, giving you an extra stop of light that may save your shot. Of course, this technique would be unacceptable if there were any pedestrians or moving cars in view; they would be unnaturally sped up if the film were projected.

1.4 180° rotating shutter.

Some cameras are equipped with a variable shutter. By varying the angle of the cutout we can regulate the exposure. For example, a 90° shutter opening transmits half as much light as a 180° opening. Some amateurs make fade-outs and fade-ins on their original film by using the variable shutter, assuming it can be changed smoothly while the camera is running. Professionals generally have all such effects done in the lab.

Since changing the camera speed also changes the exposure, you can compensate for a speed change in midshot (called speed ramping) by adjusting either the f-stop or the shutter to maintain the correct exposure. For example, a speed change from 24 fps to 12 fps would cause twice as much light to reach the film by the time it was running at 12 fps, so you could simultaneously close down the shutter angle from 180° to 90° as the frame changes, thus counteracting the exposure increase. However, the rendition of motion will be different when you alter the shutter angle, not just when you alter the frame rates.

Shutter movement is directly responsible for the stroboscopic effect. Take the example of the spokes of a turning wheel. Our intermittent exposures may catch each succeeding spoke in the same place in the frame, making the spinning wheel appear to be motionless. The camera may even catch each spoke in a position counterclockwise to the previous spoke captured, making the wheel look like it is running in reverse. Another variation, called skipping, results from movement past parallel lines or objects, such as the railings of a fence. They may appear to be vibrating. These effects will increase with faster movement and with a narrower shutter angle.

Exposure time controls the amount of motion blur recorded on each frame; due to the low sampling rate of 24 fps, a certain amount of blur is needed to make a moving object on one frame visually “blend” with the next frame. Too little blur and the motion seems too “sharp” and the viewer becomes more aware as to how few motion s...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- CONTENTS

- PREFACE TO THE THIRD EDITION

- 1 CAMERAS

- 2 FILM TECHNOLOGY

- 3 FILTERS AND LIGHT

- 4 LIGHTING

- 5 IMAGE MANIPULATION

- 6 SOUND RECORDING

- 7 POSTPRODUCTION

- 8 SPECIAL SHOOTING TECHNIQUES

- 9 PRODUCTION

- GLOSSARY

- BIBLIOGRAPHY

- INDEX

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Cinematography by Kris Malkiewicz,M. David Mullen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film & Video. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.