- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

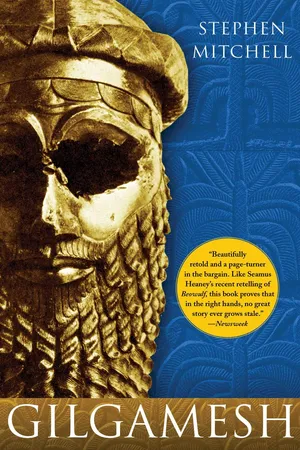

Gilgamesh is considered one of the masterpieces of world literature, and although previously there have been competent scholarly translations of it, until now there has not been a version that is a superlative literary text in its own right. Acclaimed translator Stephen Mitchell's lithe, muscular rendering allows us to enter an ancient masterpiece as if for the first time, to see how startlingly beautiful, intelligent, and alive it is. His insightful introduction provides a historical, spiritual, and cultural context for this ancient epic, showing that Gilgamesh is more potent and fascinating than ever.

Gilgamesh dates from as early as 1700 BCE -- a thousand years before the Iliad. Lost for almost two millennia, the eleven clay tablets on which the epic was inscribed were discovered in 1853 in the ruins of Nineveh, and the text was not deciphered and fully translated until the end of the century. When the great poet Rainer Maria Rilke first read Gilgamesh in 1916, he was awestruck. "Gilgamesh is stupendous," he wrote. "I consider it to be among the greatest things that can happen to a person."

The epic is the story of literature's first hero -- the king of Uruk in what is present-day Iraq -- and his journey of self-discovery. Along the way, Gilgamesh discovers that friendship can bring peace to a whole city, that a preemptive attack on a monster can have dire consequences, and that wisdom can be found only when the quest for it is abandoned. In giving voice to grief and the fear of death -- perhaps more powerfully than any book written after it -- in portraying love and vulnerability and the ego's hopeless striving for immortality, the epic has become a personal testimony for millions of readers in dozens of languages.

Gilgamesh dates from as early as 1700 BCE -- a thousand years before the Iliad. Lost for almost two millennia, the eleven clay tablets on which the epic was inscribed were discovered in 1853 in the ruins of Nineveh, and the text was not deciphered and fully translated until the end of the century. When the great poet Rainer Maria Rilke first read Gilgamesh in 1916, he was awestruck. "Gilgamesh is stupendous," he wrote. "I consider it to be among the greatest things that can happen to a person."

The epic is the story of literature's first hero -- the king of Uruk in what is present-day Iraq -- and his journey of self-discovery. Along the way, Gilgamesh discovers that friendship can bring peace to a whole city, that a preemptive attack on a monster can have dire consequences, and that wisdom can be found only when the quest for it is abandoned. In giving voice to grief and the fear of death -- perhaps more powerfully than any book written after it -- in portraying love and vulnerability and the ego's hopeless striving for immortality, the epic has become a personal testimony for millions of readers in dozens of languages.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Gilgamesh by Stephen Mitchell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Classics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

NOTES

INTRODUCTION

p. 1, Enkidu: The accent (as with Gilgamesh) is on the first syllable.

p. 3, he wrote at the end of 1916: “Gilgamesh is stupendous! I know it from the edition of the original text and consider it to be among the greatest things that can happen to a person. From time to time I tell it to people, I tell the whole story, and every time I have the most astonished listeners. The synthesis of Burckhardt is not altogether fortunate, it doesn’t achieve the greatness and significance of the original. I feel that I tell it better. And it suits me” (to Katharina Kippenberg, December 11, 1916, Briefwechsel: Rainer Maria Rilke und Katharina Kippenberg, Insel Verlag, 1954, p. 191). “Have you seen the volume published by Insel Books, that somewhat like a résumé contains an ancient Assyrian poem: the Gilgamesh. I have immersed myself in the literal scholarly translation (of Ungnad), and in these truly gigantic fragments I have experienced measures and forms that belong with the supreme works that the conjuring Word has ever produced. I would really prefer to tell it to you-the little Insel book, tastefully produced though it is, doesn’t convey the real power of the five-thousandyear old poem. In the (I must admit, excellently translated) fragments there is a truly colossal happening and being and fearing, and even the wide gaps in the text function somehow constructively, in that they keep the gloriously massive surfaces apart. Here is the epic of the fear of death, arisen in the immemorial among people who were the first for whom the separation between life and death became definitive and fateful. I am sure that your husband too will have the liveliest joy in reading through these pages. I have been living for weeks almost entirely in this impression [of them]” (to Helene von Nostitz, New Year’s Eve, 1916, Briefwech-sel mit Helene von Nostitz, Insel Verlag, 1976, p. 99).

p. 3, Austen Henry Layard: “The French were first in the field in 1842 at Nineveh and, from 1843, at Khorsabad, the eighth-century-BC capital of the Assyrian king Sargon II. But they were soon outshone and outmaneuvered by a young British traveler and adventurer, Austen Henry Layard. En route to Ceylon, the twenty-eight-year-old Layard became intrigued with stories of buried remains in the mounds near present-day Mosul which turned out to be ancient Nineveh and Nimrud, the two most fabled capitals of the Assyrians.

“Within days of starting the digging at Nimrud, Layard hit upon the first of eight palaces of the Assyrian kings dating from the ninth to seventh centuries BC, which he and his assistant eventually uncovered there and at Nineveh. In amazement they found room after room lined with carved stone bas-reliefs of demons and deities, scenes of battle, royal hunts and ceremonies; doorways flanked by enormous winged bulls and lions; and, inside some of the chambers, tens of thousands of clay tablets inscribed with the curious, and then undeciphered, cuneiform (‘wedge-shaped’) script-the remains, as we now know, of scholarly libraries assembled by the Assyrian kings Sennacherib and Ashurbanipal. By later standards it was treasure-hunting rather than archaeology, but after a few years of excavation in difficult political and financial circumstances, Layard had succeeded in resurrecting for the first time one of the great early cultures of Mesopotamia. He never made it to Ceylon.

“The most spectacular finds were shipped back to the British Museum, where the Victorian fascination with the Bible assured these illustrations of Old Testament history a rapturous reception. By the early 1850s, progress in reading the Assyrian-Babylonian script had allowed names and events to be attached to the images, among them Jehu, the ninth-century-BC king of Israel (shown paying obeisance to King Shalmanesser III), and the siege of Lachish in Judah by Sen-nacherib. Layard’s account of his discoveries, Nineveh and Its Remains (1849), soon had a huge success: ‘the greatest achievement of our time,’ according to Lord Ellesmere, president of the Royal Asiatic Society. ‘No man living has done so much or told it so well.’ An abridged edition (1852) prepared for the series ‘Murray’s Reading for the Rail’ became an instant best seller: the first year’s sales of eight thousand (as Layard remarked in a letter) ‘will place it side by side with Mrs. Rundell’s Cookery.’

“Work on the decipherment of the language of the Assyrian inscriptions was making good progress while Layard was in the field, partly owing to his discoveries. But the key to cracking the cuneiform script lay elsewhere-in a trilingual inscription of the Persian king Darius carved on the face of a cliff at Behistun in western Iran around 520 BC. (In all, the cuneiform script was used for over 3,500 years.) One of the three versions of the text used a much simpler cuneiform script with only around forty characters, which scholars soon realized must be alphabetic. Even before Layard’s excavations, by making some inspired guesses about likely titles and names, they had deciphered this script and shown the language to be Old Persian, thus of the Indo-Iranian language family (a close relative of Indo-European). Having determined the general meaning of the three texts, scholars now confirmed that the second version, written in the much more complex cuneiform script (some three hundred characters) of the tablets from Assyria, was, as many had suspected, a Semitic language (i.e., cognate with Hebrew, Aramaic, and Arabic)-what we now know as Babylonian. Many texts could be read reasonably well by the time Layard’s finds started arriving in England, but the decipherment was not officially declared to have been achieved until 1857, when four of the leading experts (including W. H. Fox-Talbot, one of the inventors of photography) submitted independent translations of a new inscription and all were shown to be in broad agreement. After two and a half millennia, the Assyrians had again found their voice” (Timothy Potts, “Buried between the Rivers,” New York Review of Books, September 25, 2003). See also Sir E. A. Wallis Budge, The Rise and Progress of Assyriology, Martin Hopkinson, 1925, pp. 68 ff.

p. 4, Akkadian: The name “Akkadian” is derived from the city-state of Akkad (near present-day Baghdad), founded in the middle of the third millennium BCE and capital of one of the first great empires in human history. By 2000 BCE Akkadian had supplanted Sumerian as the major spoken language of Mesopotamia, and around this time it split into two dialects: Babylonian, which was spoken in southern Mesopotamia, and Assyrian, which was spoken in the north.

p. 4, “On looking down the third column: George Smith, The Chaldean Account of Genesis, Sampson Low, Marston, Searle and Rivington, 1876, p. 4. “I then proceeded,” Smith’s account continues, “to read through this document, and found it was in the form of a speech from the hero of the Deluge to a person whose name appeared to be Izdubar (=Gilgamesh; Smith was guessing [mistakenly, as it turned out] that the three cuneiform signs that formed the name had their most common syllabic values). I recollected a legend belonging to the same hero Izdubar K. 231, which, on comparison, proved to belong to the same series, and I then commenced a search for any missing portions of the tablets. This search was a long and heavy work, for there were thousands of fragments to go over, and, while on the one side I had gained as yet only two fragments of the Izdubar legends to judge from, on the other hand, the unsorted fragments were so small, and contained so little of the subject, that it was extremely difficult to ascertain their meaning. My search, however, proved successful. I found a fragment of another copy of the Deluge, containing again the sending forth of the birds, and gradually collected several other portions of this tablet, fitting them in one after another until I had completed the greater part of the second column. Portions of a third copy next turned up, which, when joined together, completed a considerable part of the first and sixth columns. I now had the account of the Deluge in the state in which I published it at the meeting of the Society of Biblical Archaeology, December 3rd, 1872.”

p. 4, according to a later account: Budge, The Rise and Progress of Assyriology, p. 153.

p. 5, caused a major stir: “The London Daily Telegraph offered to fund an expedition to look for the missing part of the tablet. Smith duly set out, and on only his fifth day of searching through the spoil heaps of Nineveh-with luck that must have seemed divinely inspired-found a tablet fragment that filled most of the gap in the story” (Potts, “Buried between the Rivers”).

p. 5, Though to a modern reader it seems quaint: Here are two examples from Tablet I (the first passage in each example is a literal prose version, the second is Smith’s translation):

Gilgamesh said to him, to the trapper, “Go, trapper, and take the £arïmtu [sacred prostitute] Shamhat with you. When the animals come down to the waterhole, have her take off her robe and expose her vagina. When he sees her, he will approach. The animals will be estranged from him, though he grew up in their presence.” The trapper went off, he took the £arïmtu Shamhat with him, they set out on the journey. On the third day they reached their destination. The trapper and the £arïmtu sat down to wait. A first and a second day they sat by the waterhole as the animals came to drink at the waterhole. The animals arrived, their hearts grew pleased, then Enkidu as well, who was born in the wilderness, who ate grass with the gazelles. He came to drink at the waterhole with the animals, his heart grew pleased as he drank the water with the animals. Shamhat saw him, this primordial being, this savage from the midst of the wilderness. “Look, Shamhat, there he is. Bare your breasts, expose your vagina, let him take in your voluptuousness. Do not hold back, take his breath. When he sees you, he will approach. Spread out your robe so that he can lie on you, do for him the work of a woman. Let him mount you in his lust, and the animals will be estranged from him, though he grew up in their presence” (I, 161 ff.).

Izdubar to him also said to Zaidu: / go Zaidu and with thee the female Harimtu, and Samhat take, / and when the beast … in front of the field

(directions to the female how to entice Heabani [=Enkidu])

Zaidu went and with him Harimtu, and Samhat he took, and / they took the road, and went along the path. / On the third day they reached the land where the flood happened. / Zaidu and Harimtu in their places sat, the first day and the second day in front of the field they sat, / the land where the beast drank of drink, / the land where the creeping things of the water rejoiced his heart. / And he Heabani had made for himself a mountain / with the gazelles he eat food, / with the beasts he drank of drink, / with the creeping things of the waters his heart rejoiced. Samhat the enticer of men saw him

(details of the actions of the female Samhat and Heabani)

(The Chaldean Account of Genesis, p. 202). A few pages later, Smith comments, “I have omitted some of the details in columns III. and IV. because they were on the one side obscure, and on the other hand hardly adapted for general reading.”

The second passage comes from later in Tablet I. Smith’s translation is quite fragmentary:

“I will challenge him, mighty [ … ]. [ … ] in Uruk: ‘I am the mightiest! [ … ] I will change the order of things, [the one] born in the wilderness is the strongest of all!”

“Let [him] see your face, [I will lead you to Gilgamesh,] I know where he will be. Come, Enkidu, to Uruk-the-Sheepfold, where the young men are girt with wide belts. Every day [ … ] a festival is held, the lyre and drum are played, the £arimäti stand around, lovely, laughing, filled with sexual joy, so that even old men are aroused from their beds. Enkidu, [you who don’t yet] know life, I will show you Gilgamesh, the man of joy and grief. You will look at him, you will see how handsome and virile he is, how his whole body is filled with sexual joy. He is even stronger than you-he doesn’t sleep day or night. Put aside your audacity, Enkidu. Shamash loves Gilgamesh, and his mind has been enlarged by Anu, Enlil, and Ea [the three principal gods].” (I, 221 ff.)

I will meet him and see his power, / I will bring to the midst of Erech a tiger [!-S.M.], / and if he is able he will destroy it. / In the desert it is begotten, it has great strength, / … … before thee / … … everything there is I know / Heabani went to the midst of Erech Suburi / … … the chiefs … made submission / in that day they made a festival / … … city / … … daughter / … … made rejoicing / … … becoming great / … … mingled and /… … Izdubar rejoicing the people / went before him / A prince thou becomest glory thou hast / … … fills his body / … … who day and night / … … destroy thy terror / … … the god Samas loves him and / … … and Hea have given intelligence to his ears.

(The Chaldean Account of Genesis, pp. 203-204.)

p. 5, here is the consensus: In the following account, through p. 6, I rely heavily on Andrew George’s judicious and informative introduction to The Epic of Gilgamesh (hereafter abbreviated as EG ).

p. 5, five separate and independent poems in Sumerian: Translations of all five poems are posted on the Sumerian Literature site of the Oriental Institute, University of Oxford, at http://www-etcsl.orient.ox.ac.uk.

p. 5, as distant from Akkadian: “aussi loin de l’akkadien que le chinois peut l’être du français” (Bottéro, p. 19).

p. 6, the eleven clay tablets dug up at Nineveh: “The ‘series of Gilgamesh,’ in fact, comprises twelve tablets, not just the eleven of the epic. Tablet XII, the last, is a line-by-line translation of the latter half of one of the Sumerian Gilgamesh poems … Most scholars would agree that it does not belong to the text but was attached to it because it was plainly related material” (George, EG, p. xxviii; for an extended discussion, see A. R. George, The Babylonian Gilgamesh Epic, I, pp. 47 ff., hereafter abbreviated as BGE ).

p.6, the first Epic of Gilgamesh: “The Akkadian epic was given its original shape in the Old Babylonian Period by an Akkadian author who took over, in greater or lesser degree, the plots and themes of three or four of the Sumerian tales … Either translating freely from Sumerian or working from available paraphrases, the author combined these plots and themes into a unified epic on a grand scale. As the central idea in this epic, the author seized upon a theme which was adumbrated in three of the Sumerian tales, Gilgamesh’s concern with death and his futile desire to overcome it. The author advanced this theme to a central position in the story. To this end, Enkidu’s death became the pivotal event which set Gilgamesh on a feverish search for the immortal flood hero (whose story existed in Sumerian, but had nothing to do with the tales about Gilgamesh), hoping to learn how he had overcome death. The author separated the themes of Enkidu’s death and Gilgamesh’s grief from their original context in the Sumerian ‘Gilgamesh, Enkidu, and the Netherw...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- CONTENTS

- INTRODUCTION

- ABOUT THIS VERSION

- PROLOGUE

- BOOK I

- BOOK II

- BOOK III

- BOOK IV

- BOOK V

- BOOK VI

- BOOK VII

- BOOK VIII

- BOOK IX

- BOOK X

- BOOK XI

- NOTES

- BIBLIOGRAPHY

- GLOSSARY

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- ABOUT THE AUTHOR