![]()

1

ONE DAY OF MAGIC

AT 1:28 on the morning of December 7, 1941, the big ear of the Navy’s radio station on Bainbridge Island near Seattle trembled to vibrations in the ether. A message was coming through on the Tokyo-Washington circuit. It was addressed to the Japanese embassy, and Bainbridge reached up and snared it as it flashed overhead. The message was short, and its radiotelegraph transmission took only nine minutes. Bainbridge had it all by 1:37.

The station’s personnel punched the intercepted message on a teletype tape, dialed a number on the teletypewriter exchange, and, when the connection had been made, fed the tape into a mechanical transmitter that gobbled it up at 60 words per minute.

The intercept reappeared on a page-printer in Room 1649 of the Navy Department building on Constitution Avenue in Washington, D.C. What went on in this room, tucked for security’s sake at the end of the first deck’s sixth wing, was one of the most closely guarded secrets of the American government. For it was in here—and in a similar War Department room in the Munitions Building next door—that the United States peered into the most confidential thoughts and plans of its possible enemies by shredding the coded wrappings of their dispatches.

Room 1649 housed OP-20-GY, the cryptanalytic section of the Navy’s cryptologic organization, OP-20-G. The page-printer stood beside the desk of the GY watch officer. It rapped out the intercept in an original and a carbon copy on yellow and pink teletype paper just like news on a city room wire-service ticker. The watch officer, Lieutenant (j.g.) Francis M. Brotherhood, U.S.N.R., a curly-haired, brown-eyed six-footer, saw immediately from indicators that the message bore for the guidance of Japanese code clerks that it was in the top Japanese cryptographic system.

This was an extremely complicated machine cipher which American cryptanalysts called PURPLE. Led by William F. Friedman, Chief Cryptanalyst of the Army Signal Corps, a team of codebreakers had solved Japan’s enciphered dispatches, deduced the nature of the mechanism that would effect those letter transformations, and painstakingly built up an apparatus that cryptographically duplicated the Japanese machine. The Signal Corps had then constructed several additional PURPLE machines, using a hodgepodge of manufactured parts, and had given one to the Navy. Its three components rested now on a table in Room 1649: an electric typewriter for input; the cryptographic assembly proper, consisting of a plugboard, four electric coding rings, and associated wires and switches, set on a wooden frame; and a printing unit for output. To this precious contraption, worth quite literally more than its weight in gold, Brotherhood carried the intercept.

He flicked the switches to the key of December 7. This was a rearrangement, according to a pattern ascertained months ago, of the key of December 1, which OP-20-GY had recovered. Brotherhood typed out the coded message. Electric impulses raced through the maze of wires, reversing the intricate enciphering process. In a few minutes, he had the plaintext before him.

It was in Japanese. Brotherhood had taken some of the orientation courses in that difficult language that the Navy gave to assist its cryptanalysts. He was in no sense a translator, however, and none was on duty next door in OP-20-GZ, the translating section. He put a red priority sticker on the decode and hand-carried it to the Signal Intelligence Service, the Army counterpart of OP-20-G, where he knew that a translator was on overnight duty. Leaving it there, he returned to OP-20-G. By now it was after 5 a.m. in Washington—the message having lost three hours as it passed through three time zones in crossing the continent.

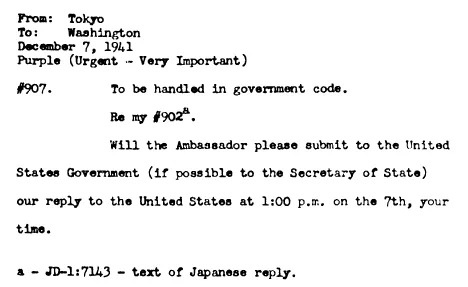

The S.I.S. translator rendered the Japanese as: “Will the Ambassador please submit to the United States Government (if possible to the Secretary of State) our reply to the United States at 1:00 p.m. on the 7th, your time.” The—“reply” referred to had been transmitted by Tokyo in 14 parts over the past 18½ hours, and Brotherhood had only recently decrypted the 14th part on the PURPLE machine. It had come out in the English in which Tokyo had framed it, and its ominous final sentence read: “The Japanese Government regrets to have to notify hereby the American Government that in view of the attitude of the American Government it cannot but consider that it is impossible to reach an agreement through further negotiations.” Brotherhood had set it by for distribution early in the morning.

The translation of the message directing delivery at one o’clock had not yet come back from S.I.S. when Brotherhood was relieved at 7 a.m., and he told his relief, Lieutenant (j.g.) Alfred V. Pering, about it. Half an hour later, Lieutenant Commander Alwin D. Kramer, the Japanese-language expert who headed GZ and delivered the intercepts, arrived. He saw at once that the all-important conclusion of the long Japanese diplomatic note had come in since he had distributed the 13 previous parts the night before. He prepared a smooth copy from the rough decode and had his clerical assistant, Chief Yeoman H. L. Bryant, type up the usual 14 copies. Twelve of these were distributed by Kramer and his opposite number in S.I.S. to the President, the secretaries of State, War, and Navy, and a handful of top-ranking Army and Navy officers. The two others were file copies. This decode was part of a whole series of Japanese intercepts, which had long ago been given a collective codename, partly for security, partly for ease of reference, by a previous director of naval intelligence, Rear Admiral Walter S. Anderson. Inspired, no doubt, by the mysterious daily production of the information and by the aura of sorcery and the occult that has always enveloped cryptology, he called it MAGIC.

When Bryant had finished, Kramer sent S.I.S. its seven copies, and at 8 o’clock took a copy to his superior, Captain Arthur H. McCollum, head of the Far Eastern Section of the Office of Naval Intelligence.

MAGIC ’s solution of the Japanese one o’clock delivery message

He then busied himself in his office, working on intercepted traffic, until 9:30, when he left to deliver the 14th part of Tokyo’s reply to Admiral Harold F. Stark, the Chief of Naval Operations, to the White House, and to Frank Knox, the Secretary of the Navy. Knox was meeting at 10 a.m. that Sunday morning in the State Department with Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson and Secretary of State Cordell Hull to discuss the critical nature of the American negotiations with Japan, which, they knew from the previous 13 parts, had virtually reached an impasse. Kramer returned to his office about 10:20, where the translation of the message referring to the one o’clock delivery had arrived from S.I.S. while he was on his rounds.

Its import crashed in upon him at once. It called for the rupture of Japan’s negotiations with the United States by a certain deadline. The hour set for the Japanese ambassadors to deliver the notification—1 p.m. on a Sunday—was highly unusual. And, as Kramer had quickly ascertained by drawing a navigator’s time circle, 1 p.m. in Washington meant 7:30 a.m. in Hawaii and a couple of hours before dawn in the tense Far East around Malaya, which Japan had been threatening with ships and troops.

Kramer immediately directed Bryant to insert the one o’clock message into the reddish-brown looseleaf cardboard folders in which the MAGIC intercepts were bound. He included several other intercepts, adding one at the last minute, then slipped the folders into the leather briefcases, zipped these shut, and snapped their padlocks. Within ten minutes he was on his way.

He went first to Admiral Stark’s office, where a conference was in session, and indicated to McCollum, who took the intercept from him, the nature of the message and the significance of its timing. McCollum grasped it at once and disappeared into Stark’s office. Kramer wheeled and hurried down the passageway. He emerged from the Navy Department building and turned right on Constitution Avenue, heading for the meeting in the State Department eight blocks away. The urgency of the situation washed over him again, and he began to move on the double.

This moment, with Kramer running through the empty streets of Washington bearing his crucial intercept, an hour before sleepy code clerks at the Japanese embassy had even deciphered it and an hour before the Japanese planes roared off the carrier flight decks on their treacherous mission, is perhaps the finest hour in the history of cryptology. Kramer ran while an unconcerned nation slept late, ignored aggression in the hope that it would go away, begged the hollow gods of isolationism for peace, and refused to entertain—except humorously—the possibility that the little yellow men of Japan would dare attack the mighty United States. The American cryptanalytic organization swept through this miasma of apathy to reach a peak of alertness and accomplishment unmatched on that day of infamy by any other agency in the United States. That is its great achievement, and its glory. Kramer’s sprint symbolizes it.

Why, then, did it not prevent Pearl Harbor? Because Japan never sent any message saying anything like “We will attack Pearl Harbor.” It was therefore impossible for the cryptanalysts to solve one. Messages had been intercepted and read in plenty dealing with Japanese interest in warship movements into and out of Pearl Harbor, but these were evaluated by responsible intelligence officers as on a par with the many messages dealing with American warships in other ports and the Panama Canal. The causes of the Pearl Harbor disaster are many and complex, but no one has ever laid any of whatever blame there may be at the doors of OP-20-G or S.I.S. On the contrary, the Congressional committee that investigated the attack praised them for fulfilling their duty in a manner that “merits the highest commendation.”

As the climax of war rushed near, the two agencies—together the most efficient and successful codebreaking organization that had ever existed—scaled heights of accomplishment greater than any they had ever achieved. The Congressional committee, seeking the responsibility for the disaster, exposed their activity on almost a minute-by-minute basis. For the first time in history, it photographed in fine-grained detail the operation of a modern codebreaking organization at a moment of crisis. This is that film. It depicts OP-20-G and S.I.S. in the 24 hours preceding the Pearl Harbor attack, with the events of the past as prologue. It is the story of one day of MAGIC.

The two American cryptanalytic agencies had not sprung full-blown into being like Athena from the brow of Zeus. The Navy had been solving at least the simpler Japanese diplomatic and naval codes in Rooms 1649 and 2646 on the “deck” above since the 1920s. Among the personnel assigned to cryptanalytical duties were some of the Navy’s approximately 50 language officers who had served in Japan for three years studying that exceedingly difficult tongue. One of them was Lieutenant Ellis M. Zacharias, later to become famous as an expert in psychological warfare against Japan. After seven months of training in Washington in 1926, he took charge of the naval listening station on the fourth floor of the American consulate in Shanghai, where he intercepted and cryptanalyzed Japanese naval traffic. This post remained in operation until it was evacuated to Corregidor in December, 1940. Long before then, radio intelligence units had been set up in Hawaii and in the Philippines, with headquarters in Washington exercising general supervision.

The Army’s cryptanalytical work during the 1920s was centered in the so-called American Black Chamber under Herbert O. Yardley, who had organized it as a cryptologic section of military intelligence in World War I. It was maintained in secrecy in New York jointly by the War and State departments, and perhaps its greatest achievement was its 1920 solution of Japanese diplomatic codes. At the same time, the Army’s cryptologic research and code-compiling functions were handled by William Friedman, then as later a civilian employee of the Signal Corps. In 1929, Henry L. Stimson, then Secretary of State, withdrew State Department support from the Black Chamber on ethical grounds, dissolving it. The Army decided to consolidate and enlarge its codemaking and codebreaking activities. Accordingly, it created the Signal Intelligence Service, with Friedman as chief, and, in 1930, hired three junior cryptanalysts and two clerks.

The following year, a Japanese general suddenly occupied Manchuria and set up a puppet Manchu emperor, and the government of the island empire of Nippon fell into the hands of the militarists. Their avarice for power, their desire to enrich their have-not nation, their hatred for white Occidental civilization, started them on a decade-long march of conquest. They withdrew from the League of Nations. They began beefing up the Army. They denounced the naval disarmament treaties and began an almost frantic shipbuilding race. Nor did they neglect, as part of their war-making capital, their cryptographic assets. In 1934, their Navy purchased a commercial German cipher machine called the Enigma; that same year, the Foreign Office adopted it, and it evolved into the most secret Japanese system of cryptography. A variety of other cryptosystems supplemented it. The War, Navy, and Foreign ministries shared the superenciphered numerical HATO code for intercommunication. Each ministry also had its own hierarchy of codes. The Foreign Office, for example, employed four main systems, each for a specific level of security, as well as some additional miscellaneous ones.

Meanwhile, the modern-style shoguns speared into defenseless China, sank the American gunboat Panay, raped Nanking, molested American hospitals and missions in China, and raged at American embargoes on oil and steel scrap. It became increasingly evident that Nippon’s march of aggression would eventually collide with American rectitude. The mounting curve of tension was matched by the rising output of the American crypt-analytic agencies. A trickle of MAGIC in 1936 had become a stream in 1940. Credit for this belongs largely to Major General Joseph O. Mauborgne, who became Chief Signal Officer in October, 1937.

Mauborgne had long been interested in cryptology. In 1914, as a young first lieutenant, he achieved the first recorded solution of a cipher known as the Playfair, then used by the British as their field cipher. He described his technique in a 19-page pamphlet that was the first publication on cryptology issued by the United States government. In World War I, he put together several cryptographic elements to create the only theoretically unbreakable cipher, and promoted the first automatic cipher machine, with which the unbreakable cipher was associated. He was among the first to send and receive radio messages in airplanes. As Chief Signal Officer, he retained enough of his flair for cryptanalysis to solve a short and difficult challenge cipher. He was a...