- 496 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

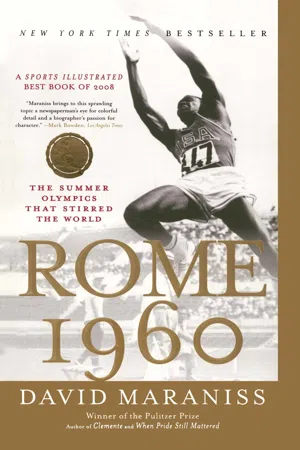

From the New York Times bestselling author of Clemente and When Pride Still Mattered, the blockbuster story of the 1960 Summer Olympics in Rome, seventeen days that helped define the modern world.

Legendary athletes and stirring events are interwoven into a suspenseful narrative of sports and politics at the Rome games, where Cold War propaganda and spies, drugs and sex, money and television, civil rights and the rise of women superstars all converged to forever change the future of the Olympics.

Using the meticulous research and sweeping narrative style that have become his trademark, Maraniss reveals the rich palette of character, competition, and meaning that gave Rome 1960 its impactful and unique essence.

Legendary athletes and stirring events are interwoven into a suspenseful narrative of sports and politics at the Rome games, where Cold War propaganda and spies, drugs and sex, money and television, civil rights and the rise of women superstars all converged to forever change the future of the Olympics.

Using the meticulous research and sweeping narrative style that have become his trademark, Maraniss reveals the rich palette of character, competition, and meaning that gave Rome 1960 its impactful and unique essence.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

ALL THE WAY TO MOSCOW

DARKNESS fell slowly in midsummer Moscow, but the Americans arrived so late that the chartered buses needed headlights to illumine the ride from the airport. Every now and then, for no readily apparent reason, the Russian drivers clicked off the lights, drove a few blocks through the crepuscular murk, then turned on the beams again. The most mundane events can be charged with mystery the first time around, and this was a first for the passengers entering the Soviet capital on the Monday evening of July 21, 1958. They were members of the first U.S. track-and-field team to visit the USSR since the start of the cold war. Out the windows, flashes of light and shadow flitted by, a hypnotic passing scene: drunken men slouched in dimly lit doorways; armed soldiers at intersections; broad avenues with little traffic other than buses whose exhaust fumes fouled the humid air; and the occasional black sedan claiming the VIP lane. When the Americans reached their hotel and checked into their rooms, they were struck by how heavy everything seemed. Bulky bedposts and thick, ponderous curtains.

Edward Stanley Temple had seen worse back home. As someone who had spent a lifetime dealing with alien environments because of his skin color alone, this one was not quite so unnerving. Moscow, to him, was just a stop on the road, another way for the coach and his athletes to get where he wanted them to go, past Russia and into history at the 1960 Olympic Games in Rome.

This leg of Temple’s improbable journey had begun three weeks earlier with a gesture of audacious confidence. As he was preparing to leave his home in Nashville for the Fourth of July weekend, he asked his wife, Charlie, to pack his suitcase with enough clothes for him to spend several weeks overseas. The request surprised her, since the schedule called for Temple, the women’s track coach at Tennessee Agricultural and Industrial State University, to be away for only four days at the national championships in Morristown, New Jersey. That was just the first stop, he explained. Although nothing had been decided yet, he predicted that he and his Tigerbelles would be chosen to go from there all the way across the Atlantic for the first-ever dual track meet between the United States and the Soviet Union.

The fact that Temple booked a Ladd Bus Company charter for the ride to New Jersey underscored his conviction of better things to come. For years his track team had traveled in two clunky station wagons—four or five girls per car—one driven by him, the other by his friend, the photographer Earl Clanton, who had coined the team’s evocative Tigerbelles nickname, a felicitous melding of tiger and southern belle. Their traditional road trips ventured deeper into Jim Crow territory, to track relays at Tuskegee Institute or Alabama State, and followed a familiar pattern. Late on a Friday, often around midnight, they broke away from the hilly campus in north Nashville, the waybacks jumbled with gym duffels, starting blocks, hammers, spikes, purses, curling irons, and meals of peanut butter and jelly sandwiches and apples packed in brown paper bags. It was best if they filled the gas tank beforehand; getting service at a station along the way could be a dicey proposition. And the fewer stops, the safer.

Temple grew up in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, and he recruited a few athletes from the projects in Chicago and New York, but most of his runners came out of rural Georgia towns like Jakin, Griffin, and Bloomingdale. They had seen Whites Only signs all their lives and knew how to keep on going. At some point there would be a shout from the back: time to “hit the fields.” It was both polite code and bleak reality, meaning pull over to the shoulder of the highway so they could scramble into the darkness for relief. As the caravan approached its destination, an order would come from the front: “Get your stuff together.” This meant rollers off, lipstick on, everything brushed and straightened. The sprinters were a free-spirited group; some chafed at Coach Temple’s rules of behavior but grudgingly obliged. “I want foxes, not oxes,” he told them. The Tigerbelles had perfected the art of emerging from the least flattering conditions looking as fresh as a gospel choir, for which they were often mistaken.

The Independence Day expedition north to what the track world called the nationals was different from the usual road trip. There was no need to hit the fields; the Ladd bus had its own lavatory. And no more peanut butter and jelly sandwiches. Once they escaped the borders of the old Confederacy, Coach Temple and his team could find more possible places to stop and eat, within means of their paltry budget, which allowed about $6 per athlete for breakfast and dinner. His top-flight runners—including Lucinda Williams, Barbara Jones, Isabelle Daniels, and Margaret Matthews—brought along suitcases even bigger than his. Like him, they figured victory would come their way in Morristown, and after that they would go on to the Soviet Union.

All of his best sprinters, that is, except the one who was not there. As a sixteen-year-old high school girl two years earlier, Wilma Glodean Rudolph had run with the Tigerbelles on the bronze-medal-winning 4 x 100 meter relay team at the 1956 Summer Olympics in Melbourne, Australia. Since then, she had trained regularly at Temple’s clinics for high school girls at Tennessee State and had graduated from Burt High in Clarksville, a tobacco town forty-five miles northwest of Nashville, where she also starred in basketball. All of her accomplishments had been stunningly against the odds, from the time she had been born two months premature, weighing less than five pounds. At age four, she had endured scarlet fever, double pneumonia, and polio, crippling her left leg and forcing her to wear orthopedic shoes and metal leg braces for several years. By her adolescence, after years of weekly bus trips for treatments at a clinic in Nashville, she had overcome all that and blossomed into a lithe, flowing runner. Now her freshman year in college was approaching, and Wilma was about to become a full-fledged Tigerbelle, but for the time being she was out of action. If outsiders asked about her, Temple told them she had appendicitis. In fact, she was about to give birth to a baby girl. She had gone from Olympic medalist heroine to expectant unmarried mother, alone and mortified.

Temple had another saying: “It’s a short distance between a pat on the back and a kick in the ass.” He had seen how people had soured on Rudolph when she got pregnant. And one of his own iron-clad rules was no mothers allowed on the team. But Wilma was so different, the sweetest girl he had ever met, and she ran with such beautiful ease. Her older sister Yvonne in St. Louis would take the baby temporarily, she said, if Coach let her come back. Temple relented. Wilma could join the Tigerbelles when they returned from this trip.

Women’s track and field was an odd little outpost on the frontier of sports in 1958 America, forlorn and largely scorned. Female athletes were not recognized by the National Collegiate Athletic Association. Only a few colleges, most of them historically black schools in the South, had track-and-field programs, but even they competed under the rules of the Amateur Athletic Union, not the NCAA. When Temple was named head coach at Tennessee A&I State after graduating in 1950, it was because nobody else wanted the job. His starting salary was $150 a month, which, when added to his pay for teaching social science courses, brought in a yearly sum of $5,196. His only other enticement was that he could move from East Dormitory room 305 (where he had survived four years on the boisterous floor with the sarcastic motto “Three-o-five will keep you alive”) down to a larger room on the first floor. His first team budget was under $1,000. The campus’s old cinder track encircled a football field and was often torn up by behemoths’ cleats; Temple was constantly raking it himself. When weather forced his Tigerbelles indoors, they ran in a gym barely fifty yards long where they were in danger of slamming into a wall if they failed to negotiate a double doorway leading out to the hall.

By the mid-fifties, even after Temple had established his program and led it to a national title, the athletic department still would not give him a desk, let alone an office. He shared a cramped cubbyhole with his wife, who was campus postmistress, and borrowed her desk. There were no scholarships for his athletes, so he found them work-study jobs at the post office. As minimal as these conditions were, Tennessee State at least had a program, more than most schools could say, and a winning one at that. Tuskegee had paved the way in the 1940s, but by the late fifties, the Tigerbelles dominated.

Aside from those two black Southern colleges, most of the teams competing at the nationals were northern big-city AAU clubs: Queens Mercurettes, Chicago Comets, New York Police Athletic League, Cleveland Recreation Department, Liberty Athletic Club of Boston, South Pacific Association of Los Angeles, German-American Athletic Club of New York. None of those squads had enough talent or depth to mount a challenge to Tennessee State at Morristown. By the end of the day on July 5, the Tigerbelles had won the team title by amassing 110 points, more than twice as many as the second-place Mercurettes, and all of their top sprinters had won, including the relay foursome of Daniels, Williams, Jones, and Matthews, who set a new American women’s record at 46.9 seconds.

Along with the winning relay team, the top two finishers in each of nine events qualified for the combined squad of men and women competing in the unprecedented track meet against the Soviets to be held in Moscow at the end of the month.

By the end of the tournament, AAU officials had yet to name a coach for the women’s squad. Temple had heard that they were leaning toward a white coach from the New York Police Athletic League. He also believed that he had one key ally on the board making the decision that night, Frances Sobczak Kaszubski of Cleveland. Like him, Kaszubski carried her own outsider’s burden in the world of amateur sports. Only ten years earlier, when she had competed as a discus thrower at the 1948 Olympics, she had been so disregarded by the male-dominated U.S. Olympic Committee that she had to pay her own way, an experience that at once demoralized her and drove her to devote her life to ensuring that girls coming later had more support. Now, as the top woman representative on the AAU track-and-field committee, she respected Temple and what his women had endured in the face of prejudice. She also realized that, for all practical purposes, without the Tigerbelles there would be no U.S. women’s team. Temple looked up to Big Kaszubski, who stood 6-foot-1, towering 5 inches over him. Mutt and Jeff, he called them. She was tough, with her Kaszubski Rules of Order, and could use her size to intimidate, he thought, but she was also sympathetic.

To emphasize how much he wanted the coaching job, he presented his case to her in dramatic terms that night. “The brass came in from New York,” Temple later recalled. “They had this big tent, and they were going in this tent, and Frances was going to be there, and I wasn’t. And I said, ‘Frances, you going to that meeting?’ She said yes. I said, ‘Well, now, let me tell you something.’ And this is exactly what I told her. I said, ‘I got eight people on this team: everybody in the hundred, everybody in the two hundred, the relay, long jump, hurdles.’ I said, ‘We came up here on a chartered bus, and that bus is leaving here at eight o’clock tomorrow morning.’ I said, ‘Now, you go in there and tell them that if I am not on this trip, all eight of ’em will be on the bus going back to Nashville, Tennessee.’ Her eyes got as big as fish, and when they came out of the meeting, she said, ‘Ed Temple, you’re the coach!’”

THE OLYMPIC ideal was of pure athletic competition separated from the ideologies and international disputes of the modern world. But that was an impossible notion, and there was no pretense of separating sports and politics in the first dual track-and-field meet involving the two superpowers of the cold war era. Sports officials first broached the subject during an informal summit meeting at the Soviet quarters in Melbourne at the 1956 Olympics. A long night of food, drinks, and conversation about future head-to-head competitions ended with a firm handshake between team leaders Daniel Ferris of the U.S. and Russian Leonid Khomenkov. But the reality could not take shape without political diplomacy, and that came later, on January 27, 1958, when Soviet ambassador Georgi Zaroubin and U.S. ambassador S. B. Lacy concluded three months of negotiations by signing the US-USSR Exchange Agreement. After icy relations for so many years, with little cultural contact between the two nations, finally there would be regular exchanges in industry, agriculture, medicine, music, art, film, theater, and athletics.

The home and away exchange pattern had been arranged in sports even before the pact was officially signed. In the first year, ice hockey and basketball teams would play in Russia, while wrestlers and weight lifters competed in the U.S.—all culminating with a titanic track-and-field meet at Lenin Stadium in Moscow in late July. Both governments praised the agreement. The newspaper Pravda welcomed it as “part of the principle of peaceful coexistence,” and Soviet Olympic officials were quoted in Izvestia saying that the sports teams had “a lot to learn from each other.” The only vocal opposition came from right-wing critics in the U.S. who denounced any accommodation of the Communists. In response, the State Department argued that the exchanges could only help the image of the United States, which, as one internal memo stated, “had been distorted beyond any pretense of accuracy” by Soviet propaganda. One of the most troubling images had to do with race, America in black and white.

By the time the roster of the U.S. track team was set at the national championships in early July, there were few signs of a cold war thaw. No sooner had David Edstrom, a young decathlete from the University of Oregon, made the team than he began to wonder what was in store. Leafing through a New York newspaper, Edstrom saw photos of a Russian mob outside the West German embassy on Moscow’s Bolshoya Gruzinskaya Street pelting the building with slabs of concrete and splattering the walls with bottles of purple ink. Two days later the papers showed a similar crowd gathered at the U.S. embassy in Moscow, waving placards and denouncing America as a land of fascist dogs. Both rallies were carefully directed by Soviet officials—a bit of propagandistic stagecraft meant to counterbalance earlier demonstrations in Bonn and New York protesting the recent execution by hanging of former Hungarian leaders Imre Nagy and General Pal Maleter. Nagy and Maleter had become martyrs in the West: Communists who had turned against their Soviet overseers to help lead the ill-fated Hungarian Revolution of 1956.

All of this was strange and unsettling to Edstrom, who, like his teammates, had never been to the Soviet Union. “I thought, What is going on there?” he recalled. “It was kind of scary thinking about going over. I didn’t know what to expect.”

American officials were more concerned about the prospects of the track meet itself, how the results might be used by them—or, to their minds, misused by the Soviets—for propaganda purposes. Here the ironies of different concepts of equality came into play. Following a long-standing tradition among European nations, the host Russians declared that the point totals of men and women would be counted together to determine a winner. U.S. officials feared that their women, considered inferior to their Soviet counterparts, would drag them to defeat, and wanted to split men and women into separate competitions. This was the norm in the States, where the role of women was so minimized that Track & Field News, the bible of the sport, did not even cover the women’s championships in Morristown. Renewed negotiations got so sticky that one day, as Temple was putting his team through twice-a-day drills at a high school track in New Jersey, where it had set up training camp awaiting the overseas trip, Kaszubski approached him with grim news. “Ed,” she said, “we might not go on this tour to Russia.” Another form of segregation, Temple thought. Maybe he wouldn’t need that big suitcase after all.

In the end, after keeping the women’s team in limbo for a few days, U.S. officials concluded that they would look foolish refusing to participate because of the gender issue. Among other things, that would provide the Soviets with more rhetorical ammunition, reinforcing their accusations that under capitalism many athletes were treated like second-class citizens. As the Soviets waged a propaganda struggle for the hearts and minds of people around the world, they consistently pounded away at the theme of racial segregation in the American South. State Department officials and foreign policy advisers in the Eisenhower White House were reluctant to provide them with yet another equality issue. A National Security Council task force on international communism had concluded that summer that one of the most effective ways to counteract Soviet propaganda was to show the world more than white males. “We should make more extensive use of nonwhite American citizens,” the task force report stated. “Outstanding Negroes in all fields should be appealed to in terms of highest patriotism to act as our representatives.” It was partly with that in mind that the White House financed the trip to Moscow with funds from the President’s Special International Program for Cultural Presentations.

“CLIPPER AAU” was painted on the side of the Pan American Airways DC-7C that rumbled down the runway of New York’s Idlewild Airport on the morning of July 20 and charted a northern arc across the Atlantic. The U.S. team was seventy-three strong counting coaches and officials. Uncertainty about what lay ahead was evident in the cargo hold, which contained four hundred pounds of extra food in case the Russian fare was inedible. It was the largest delegation of American track-and-field stars ever assembled outside the Olympics. Six previous Olympic gold medal winners were aboard, including shot-putter Parry O’Brien, who captained the squad, and hurdler Glenn Davis, who had been chosen to carry the American flag. But the best among them, still looking for his first gold medal, fit whatever notion the government might have had of an “outstanding Negro.”

This was Rafer Lewis Johnson, who had won the U.S. decathlon championship in Palmyra, New Jersey, on the same day the Tigerbelles swept the sprints up in Morristown. Rafer Johnson was considered an exemplar of sound mind and sound body—a student body president at UCLA, intelligent, movie-star handsome, classically sculpted at six-three and two hundred pounds, with long legs and a muscular frame. There was an aura about Johnson that lifted him above the crowd. He was ferociously competitive yet not as self-centered as most athletes, with a universal perspective that came from growing up black, the son of a factory worker at an animal food processing plant, in a historically Swedish town in central California. Johnson boarded the plane with an unopened letter from his college coach, Ducky Drake, in his pocket, and failure etched in his mind.

It was at the 1956 Olympics in Melbourne that Johnson had suffered the most painful loss of his young career. He had gone down to Australia as a gold medal favorite, so talented that he qualified for the team not only in the ten-event decathlon but also separately in the long jump, then called the broad jump. While warming up, he pulled a muscle in his right leg, an injury that forced him out of the broad-jump competition but did not sideline him completely. He battled on in the punishing...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Colophon

- ALSO BY DAVID MARANISS

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- A BRIEF PREFACE

- 1 All the Way to Moscow

- 2 All Roads to Rome

- 3 No Monarch Ever Held Sway

- 4 May the Best Man Win

- 5 Out of the Shadows

- 6 Heat

- 7 Quicker Than the Eye

- 8 Upside Down

- 9 Track & Field News

- 10 Black Thursday

- Interlude: Descending with Gratitude

- 11 The Wind at Her Back

- 12 Liberation

- 13 The Russians Are Coming

- 14 The Greatest

- 15 The Last Laps

- 16 New Worlds

- 17 The Soft Life

- 18 “Successful Completion of the Job”

- 19 A Thousand Sentinels

- 20 “The World Is Stirring”

- APPENDIX

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- BIBLIOGRAPHY

- SOURCES

- NOTES

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Rome 1960 by David Maraniss in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & 21st Century History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.