- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

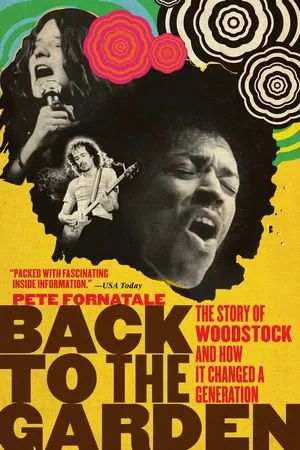

The definitive oral history of the seminal rock concert, Woodstock—three days of peace and music and one of the most defining moments of the 1960s—with original interviews with Roger Daltrey, Joan Baez, David Crosby, Richie Havens, Joe Cocker, and dozens of headliners, organizers, and fans.

On Friday, August 15, 1969, a crowd of 400,000—an unprecedented and unexpected number at the time—gathered on Max Yasgur’s farm in upstate New York for a weekend of rock ‘n’ roll, the new form of American music that had emerged only a decade earlier. For America’s counterculture youth, Woodstock became a symbol of more than just sex, drugs, and rock ‘n’ roll—it was about peace, love, and a new way of living. It was a seminal event that epitomized the ways that the culture, the country, and the core values of an entire generation were shifting. On one glorious weekend, this generation found its voice through one outlet: music.

Back to the Garden celebrates the music and the spirit of Woodstock through the words of some of the era’s biggest musical stars, as well as those who participated in the festival. From Richie Havens’s legendary opening act to the Who’s violent performance, from the Grateful Dead’s jam to Jefferson Airplane’s wake-up call, culminating in Jimi Hendrix’s career-defining moment, Fornatale brings new stories to light and sets the record straight on some common misperceptions. Illustrated with black-and-white photographs, authoritative, and highly entertaining, Back to the Garden is the soon-to-be classic telling of three days of peace and music.

On Friday, August 15, 1969, a crowd of 400,000—an unprecedented and unexpected number at the time—gathered on Max Yasgur’s farm in upstate New York for a weekend of rock ‘n’ roll, the new form of American music that had emerged only a decade earlier. For America’s counterculture youth, Woodstock became a symbol of more than just sex, drugs, and rock ‘n’ roll—it was about peace, love, and a new way of living. It was a seminal event that epitomized the ways that the culture, the country, and the core values of an entire generation were shifting. On one glorious weekend, this generation found its voice through one outlet: music.

Back to the Garden celebrates the music and the spirit of Woodstock through the words of some of the era’s biggest musical stars, as well as those who participated in the festival. From Richie Havens’s legendary opening act to the Who’s violent performance, from the Grateful Dead’s jam to Jefferson Airplane’s wake-up call, culminating in Jimi Hendrix’s career-defining moment, Fornatale brings new stories to light and sets the record straight on some common misperceptions. Illustrated with black-and-white photographs, authoritative, and highly entertaining, Back to the Garden is the soon-to-be classic telling of three days of peace and music.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Back to the Garden by Pete Fornatale in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Saturday

FOUNDERS, QUILL, THE KEEF HARTLEY BAND, THE INCREDIBLE STRING BAND

Tom Malone: Friday night’s show ended late and we stayed up all night on the hill, as it was too dark to find our way back to the car. With the break of dawn illuminating the hillside, we awoke to find the population on the hill greatly reduced and open space before us. Seizing the opportunity to move closer, we picked up our trusty tarp and moved down the hill a few hundred feet closer to the stage and we put our wet sleeping bags on the wooden barrier wall between the stage and the crowd to dry in the sun. After establishing our new location, it was time for me to feed the troops. Two would hold the spot on the hill while the rest of us went to the car to cook breakfast, which consisted of pancakes and Kool-Aid.

Before we jump headlong into the second day of music, let’s take a step back and meet the movers and shakers who set the Woodstock juggernaut in motion.

John Roberts: This started out as a lark entirely. We came to the idea of writing a sitcom about two young men with a lot of money who get into business adventures. The only problem was that we didn’t have enough business experience to come up with episodes. So we decided to solve that problem by taking out an ad in the Wall Street Journal: “Young Men with Unlimited Capital Looking for Interesting and Legitimate Business Ideas."

John Morris: Michael and Artie's lawyer, Miles Lourie, had read an ad in the Wall Street Journal saying “Young Men with Unlimited Capital Looking for Interesting Investment”—it really was an ad in the paper. And they met with John and Joel, but what they really wanted to do was open a studio in Woodstock, and John and Joel had a studio on Fifty-seventh Street, and they didn’t really want another studio.

Joel Rosenman: In January of 1969, Mike Lang and Artie Kornfeld came to see John Roberts and me. They had an idea for a retreat recording studio in New York, and from that little idea Woodstock somehow happened eight and a half months later.

John Roberts: Miles Lourie had a couple of young clients named Mike Lang and Artie Kornfeld, who wanted to build a recording studio in Woodstock, New York, and thought we should meet because we’d have things to talk about.

Michael Lang is the face of the Woodstock founders to this day.

Ellen Sander: Michael had blond curly hair like a halo. He had a very kind of, oh, like, kind of a Michael J. Pollard face. He just had a sweet face. He was the quintessential hippie.

John Morris: "The curly-headed kid" [laughter]. We named him that early and it stuck! He had an interesting energy. He was very hip, of the era, a bright kid who had vision and saw that this could be turned into a festival and could make sense. There had been festivals before. What Michael wanted to do was to put on a three-day outdoor music event, and that’s what we made happen.

Ellen Sander: Michael is a radiant soul; he was very gentle and a supremely intelligent person. He just is the kind of person who, when he walks into a room, you turn around and you look at him and you go, “Wow, who’s that?” because he just seems to radiate something very appealing and very, very sweet. And I could see why musicians and creatives would gravitate toward him. I had no idea he was into production of this scale.

Michael Lang: I had been thinking about doing a series of concerts in Woodstock. And I had mentioned it to Artie. We used to kick it around every now and then, and then we got the idea of opening a recording studio up there, because it was such a good area for that. Bands liked it, and there were a lot of people living there—the Band and Janis Joplin and her band and Dylan and parts of Blood, Sweat and Tears—just lots of different producers and a lot of musicians coming in and out. Part of the plan was to have a rock concert to help promote the new studio.

Joel Rosenman: Within a very short period of time, we had enough written material to look at so we knew conclusively between ourselves that [the recording studio] was not the kind of project that we wanted to get involved in.

Michael Lang: One evening, we thought, Well, what if we did it all at once? And we thought, Well, it would probably be a good idea to do this festival, I remember at the time, and the studio also, and one sort of evolved out of the other, and make it a yearly event. Great way to kick it off, and it was also a great way to sort of culminate all these smaller events that had been going on for the past couple of years. Just get everybody together and look at each other and see what we’re here about.

Joel Rosenman: It was that little addendum to their project proposal that caught our eye. I remember saying to John, “This is really a yawn, don’t you think?” And he said, “There’s no way that we would want to get into this project.” And I said, “But you know the idea of having a concert with those stars. Why don’t we just skip the studio idea and just do a big concert? We could make a fortune.” And he said, “This is not what they’re proposing.” And I said, “Those guys will go for anything.” I was wrong about that. They fought tooth and nail because they had already been to a couple of concerts. They knew what a rocky road you had to travel. They knew how difficult it was to get through a rock concert with your wallet and your hide intact.

Artie Kornfeld: And it just sort of came together. Michael talks about “How did it all happen?” He says, “Talking with Artie.” And I would say that’s how it happened. Talking with Michael and Linda [Kornfeld's wife]. I always feel Linda had as much to do with it as Michael or I. I was the music business guy, and Michael was the hippie, and Linda was in the middle. She was the spirit. When people say they never knew what was going to happen, if you ask Michael—this was before Joel and John—or if Linda was alive, we knew what was going to happen because we guessed. People would come. We talked about rain and what would happen. It would probably be a free concert because you never could control a crowd that big. And what the political ramifications would be. And we talked about how it would have to be nonpolitical to be political. And how we would have to deal. That was basically talked out that night, that first night, probably behind some Colombian Blond.

John Roberts: As it happens, the night before these guys came to see us, I’d seen the movie Monterey Pop. I had just been struck by the energy and the beauty and the music and the excitement of that particular event. I said to Michael and Artie, “You mean sort of like a Monterey Pop?” and they said, “No, no, no, nothing like that; you know, nothing big like that; just a little, a little thing, maybe a couple of thousand people.” And Joel and I talked about this for a while and said, “You know, we really like this rock party idea a lot better than we do your recording studio, so why don’t we do that instead?” And they said, “No, come on, we really want to do this recording studio.” And we said, “Okay, fine, we’ll do the rock festival first, we thought of then as a party, we’ll do the party, we’ll charge admission and we’ll use the profits to build a recording studio—and since they had nowhere else to go—and they have about as much credibility as we did, which is to say none at all—they said, “Sure, that sounds fine to us.” So that’s how Woodstock was born.

Thus, the four began organizing the unprecedented event. Little did they know it would change the way rock ’n’ roll was viewed by millions. They were an unlikely team, two squares, and two hippies. They had their run-ins and inherent conflicts.

Michael Lang: I guess my job, aside from assembling this band of men and women, was to mumble at the authorities to get us through this. John and Joel were either adventurous enough or crazy enough to join us, and the four of us went off to assemble this little event. It went on to have a profound effect on our lives and other people’s lives.

Midway through Friday, Artie Kornfeld, Mike Lang, and John Morris had conferenced about the current state of the festival. The fences were down. People were getting in for free. The sheer population of the festival was overwhelming their capabilities. It was still about the music. It was still about entertaining. But it was no longer about making money. The priority of the festival founders was to avoid total pandemonium.

Artie Kornfeld, as captured in the Woodstock film, seemed pretty relaxed about the whole thing.

Artie Kornfeld: It’s worth it. Just to see the lights go on last night, man. To see the, just to see the people stand up, man, it makes it worth it. It’s, you know, I mean, I feel there, there will be people that, you know, there’s people out there that like really don’t dig it. Very few of them there. But you know, it really is to the point where it’s just family, man.

Family or no family, someone had to foot the bill, and it certainly wasn’t Artie Kornfeld. Joel Rosenman and John Roberts, the men responsible for fiscally backing the festival, were not nearly as groovy about the whole thing.

John Roberts: I think if I’d been privy to that conversation when it took place on August 17, 1969, I would have been pretty ticked off about it. We were the financial partners—we were the ones who were charged with cleaning it up, and paying all the bills, and making sure that all the lawsuits were taken care of afterwards. Since Michael and Artie didn’t really have that much of a financial stake in it; in fact, they had no investment in it personally—they were profit participants—we felt, you know, that they were less than helpful and responsible about the aftermath.

Of course, the financial reality of the situation was the last thing on the minds of the folks laid back in Yasgur’s field, gearing up for the second day of music. As we saw from the juggling that produced the opening-night order, the Woodstock lineup card was by no means etched in stone. It was clearly a case of necessity being the mother of invention. From the originally designated start time of 4:00 p.m. Friday to the actual closing time of 10:30 a.m. on Monday, traffic, weather, logistics, money matters, and old-fashioned music business clout were the real determining factors of this rock ’n’ roll variation of who’s on first. For all its peace-and-love trappings, Woodstock was firmly grounded in business, and very much beholden to the show business grid in place at the time. Woodstock would smash this paradigm to smithereens and render it irrevocably obsolete in its aftermath.

Hard-nosed agents and managers looking for the best billing, not to mention the dollar bills that they could get for their clients (and themselves, of course) ruled the day. There was also a lot of “It’s not what you know, it’s who you know” going on. As we’ve seen, Bert Sommer got the gig because of his association with Artie Kornfeld; Santana was there purely as a result of the clout of Bill Graham; and Saturday’s opening act was there strictly through a connection with festival organizer Michael Lang.

Arthur Levy: Quill was one of the bands that were booked by Mike Lang’s company, Amphion. That’s why Quill was there. They were the opening band on Saturday. They are probably the only band of the whole weekend that was not a nationally known band. They were a Boston band. They had a record out. Their drummer was a famous guy named Roger North. He invented the North drum, which was a curved drum. Those drums became very popular with rock drummers. Curved tom-toms. They never really got their due. I roadied with them for about a week after college. They were kind of jazzy blues–based. They had some pop songs. They sounded like a lot of the other Boston bands at the time—Beacon Street Union and Far Cry. You know, that kind of bluesy psychedelic, stretched-out, jazzy, sometimes modal sound. They were a great band.

Quill was indeed a Boston-based band and a regional attraction along the Northeast corridor. Lang knew their manager from his Florida head shop days and conspired with him to put Quill on the bill for a couple of reasons. One was precisely because they were still largely unknown, and Michael was cocky and prescient enough to believe that an appearance at Woodstock (and hopefully in a movie about it) side by side with all the giant, headline, established recording stars scheduled to be there could be the launching pad to instant fame and fortune. (He was right, of course, but that band turned out to be Santana, not Quill. In the words of Maxwell Smart, “He missed it by that much!”)

The second reason to have them around turned out to be a bit more successful. Lang called on Quill to quell growing community opposition and fears about the festival by “volunteering” them to do a series of free concerts at local prisons, hospitals, and mental institutions leading up to the big weekend. The band itself ranked this “minitour” among the weirdest it had ever done. Rock audiences at the time were often described as crazy and out of control, but Quill actually did a number of shows for audiences that were composed of people who were certifiably insane or convicted outlaws.

As quietly as Joan ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Dedication

- Foreword: Bring Back the Sixties, Man; by Joe McDonald

- Introduction

- Players

- Friday

- Saturday

- Sunday

- Epilogue: The Whole World Goes to Woodstock

- Acknowledgments

- Photographic Insert

- Notes

- Copyright