![]()

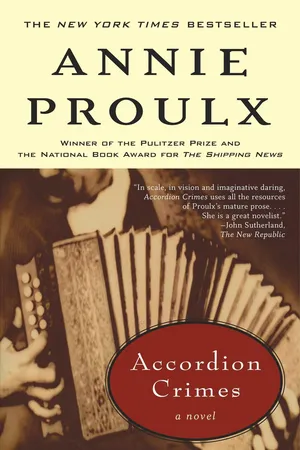

Don’t Let a Dead Man Shake You by the Hand

A PlANO ACCORDDION

A new owner

There was a truck parked on the lawn, with a hand-lettered sign in the windshield: FOR SALE $400. In the driveway a sedan panted, crowded with dim people, the back seat writhing with children, and lashed to the roof a long metal cow-feed trough. The wife’s posture in the front seat marked her as pregnant. The driver’s door stood open admitting a torrent of small black mosquitoes while the driver, Buddy Malefoot, a muscular man in white jeans and white rubber boots, a pearlized raccoon foot he’d found in an oyster hung on a chain around his neck, leaned under the truck hood jiggling wires, hooking his finger under belts to gauge their stretch, reading the bone-dry oil dipstick, then coming out from under to kick the flaccid tires with his good foot. He had a bony, rectangular face like a box, the jaw as wide as the brow, the top of his head squared off, and two jug ears that had resisted the adhesive tape of his infancy. His greasy cap sat high on black curls. He was right-sided, from a mole on his right ear, to his dexter eye, larger than the other, five long hairs near his right nipple, fingernails that grew faster on his right hand, a longer right leg and a foot a full size beyond the left. In the house a shape hovered behind the screen door, cracked it open, but Buddy held up his hand and shook his head, got in his sedan and backed out.

“Idn’t it no good?” The voice came from his father, Onesiphore, in the back seat smoking a cigarette, a man with the same square jaw as his son but stubbled with white, his yellowed hair crested, eyeglass lenses reflecting the rice fields and watery sky.

“No damn good at all. Look like hell struck with a club.” He had a smudge of grease like a caste mark on his forehead.

“Yeah, well, hate to see you spend that compensation money ennaway. Seem like y’all got a TV and an accordeen. You ought a save some of it.” He flipped the cigarette out the window.

“What I think, too,” said the daughter-in-law up front, half turning and presenting Onesiphore with her buttery profile. She wore a striped maternity minismock, and her bare thighs were stippled with mosquito bites.

“Seem like it was me got hurt. Seem like you forget don’t nobody tell me what to do. Va brasser dans tes chaudieres.”

The sedan slouched over the road on its bad shocks, squatting on the corners.

“I’ll tell you what to do,” said the back seat. “Y’all drive straighter or I’ll put a chair leg to you. You ain’t so big I couldn’t make you dance. I want to get home and see that accordeen good.”

“That’s right, Papa, make your poor hurt-footed son dance.”

“Your foot’s as good as mine. I hope it’s a D chuned.” Onesiphore Malefoot craned over the front seat to look at the black case resting between his daughter-in-law’s feet.

“Yeah? Like to sec you walk on it for more’n a minute. Told you, it’s aC.”

“Me, oh yeah, I’m gonna like to have a D. That beauty Ambrose Thibodeaux got, that old Major?”

“Dream along.”

“One time a son wouldn’t speak to his father like you, when I was young we lived at home, ate the good homegrown food, oh yeah, none of the supermarket food, but sacamité, the good okra gumbo, boudin like you can’t get no more, yes, oh yeah, then the kids were good—trouble started, and this is true, when they made the kids go to school, talk only américain. You, you and Belle used to talk French, perfect French, when you was little, now I don’t hear a word, and the grandkids, they don’t know a cheeseburger from a tortue ventre jaune. ” He lit another cigarette.

“Yeah? See how far you get out on the rig talkin French. These oil guys come here from Texas, Oklahoma, they got the money, they hand out the jobs, everything, bidness strictly American and you got to make your reports, all that the same way. What good is French to me? It’s like this secret language don’t work. It’s like kids doing pig Latin, lay ovelay ouyay. It’s OK for home, talk with the family, sing songs in.” His right eye fluttered, a tic brought on by the strain of conversing with his father. One of the children was lying on the back window shelf; the other, Bissel, crouched on the floor arranging stray pieces of gravel on his grandfather’s boot toe. (Sixteen years later Bissel, who was playing drums in a disco band in Baton Rouge, came back for a visit, saw ten thousand screaming people give the old man a standing ovation at the Cajun Music Tribute. “That’s my fucking grandfather,” he said furiously to his girlfriend as though it had been a secret kept from him all his life. When the old man died of trichinosis Bissel switched to accordion, imitated his grandfather’s singing style with eerie accuracy for a year, then slid over into swamp pop.)

“Grandpa, did you see a turtle when you were little?”

“See him! We ate him! Catch him in the summer when the swamp dried up, dig him out. Sometimes we find it after the thunderstorm. Keep him in a pen until we ready to eat him. You get the woman turtle full of eggs you got something good. We use to feel, feel that turtle with our little fingers, see can we feel eggs. Maman fricassee the meat, and the best treat is the yolk of the egg right there on your plate, taste just like chicken. You kids never ate no turtle yet? It’s good! You know, you cook them eggs all day and all night and all the next day and the white never get hard. You got to suck it out of the shell, they got a shell like leather. I don’t see one of them turtles for a long time, couple of years. Smell that café! Always down this road a good smell of cafe, oh yeah. Me, I can use some of that. Let’s hurry up and get home. Á la maison, mon fils! That petit noir is already jumping in my mouth.‘Le café noir dans unpaquet bleu, leplusje bois, le plus je veux’ “he sang in his celebrated voice, vibrant and keening, the wailing style anciently linked to the music of the vanished Chitimachas and Houmas. “Me, I say we gonna get more rain. See out there?” A mass of blue-black cloud was moving in from the Gulf. Only his daughter-in-law glanced to the southwest and nodded to foster the illusion that they were conspirators, allied against Buddy and Mme Malefoot. Onesiphore patted her shoulder and sang on, smoking, as the sedan rolled through the hot, flat country.

The Malefoot family—their enemies said the name derived from malfraty, or gangster—was a tangled clan of nodes and connecting rhizomes that spread over the continent like the fila of a great fungus. Anciently they came from France in the seventeenth century, crossed the North Atlantic to Acadie in the New World, ignored the British when France ceded the land to England who renamed it Nova Scotia and demanded oaths of allegiance. The Malefoots and thousands of others along the littoral of the Baie Frangaise ignored the preposterous request, a lack of enthusiasm the British interpreted as treason. Thousands of the Acadians were shipped away to the American colonies, some made their own way to refuge. The Malefoots went first to St. Pierre, then to Miquelon, scraps of rock off the coast of Newfound-land, then were shipped back to France where they languished for months, crossed the ocean again to Halifax, and from Halifax took ship to New Orleans in French Louisiana, an ill-timed choice, for a few years after they arrived the territory was ceded to Spain. The refugees traveled north and west into the hot, dripping, watery country of the Opelousas, Attakapas, Chitimachas, Houmas, to the Acadian coasts, the bayous Têche and Courtableau, learning to pole fragile bateaux and live in the humid damp. They mixed and mingled, blended and combined their blood with that of local tribes, Haitians, West Indians, slaves, Germans, Spanish, Free People of Color (many with the name Senegal, for their homeland river), négres libres and Anglo settlers, even américains, shaping a méli-mélo culture steeped in French, and the accordion, borrowed from the Germans, livelied the kitchen music of the prairie parishes, the fiddle had its way in the watery parishes.

Along the great bayous stretched alluvial deposits of marvelously fertile loam. In the Attakapas country the Malefoots planted cane and corn and worked the plantations alongside imported Chinese laborers, driving big sugar mules, though no Malefoots lived in fine mansions; in the Opelousas, their crops were small-farm cotton and corn, sometimes worked on shares. They kept a yam patch, rows of Irish potatoes.

They built their houses on islands and back up the bayous in the Creole style, the houses standing above the ground on cypress pillers, the broken-pitched roofs borrowed from the West Indies that covered built-in porches and outside stairs with a fausse galerie roof extension to keep the slanted rain from striking in. They smoothed the inside walls with calcimined mud and moss, grew Blue Rose rice, and in the Atchafalaya Basin, the great freshwater swamp, they gathered moss, shot alligators, poling through the marsh where snowy egrets took flight before them like tablecloths shaking, threading the briny maze of quaking earth, oyster grass, wire grass to the edge of the Gulf. In the Gulf the Malefoots, once cod fishers and whale killers of the North Atlantic, dragged for shrimp, tonged oysters, fished, and, since 1953 when the government authorized offshore drilling, worked on the oil rigs, but had not forgotten the slow glide of the pirogue through black channels, the hiss of the boat as it parted the grass, the nutria in the trap, la belle cocodrie, snout brilliant with wet duckweed. Malefoots enveloped in whining clouds of mosquitoes, slapping at blood-mad deerflies, still poled through shimmering water, sky and marsh grass, but they complained that it was all changing, with alien water hyacinth choking the waterways and the shrimp nurseries dying since the Army Corps of Engineers had blocked the natural flow of the delta-building Mississippi with their levee system, cutting off the rich silt deposits that had traveled all the way from the heartland of the continent and that had fed the great marshes forever, now spilling the silt wastefully into the ocean. The swamps and marshes were dissolving, sinking, shrinking away. (A generation later, five hundred square miles of land had melted into water. Men closed off the saline marshes, flushed them with fresh water for a crop of rice, pumped them dry for cattle pasture and the quick money that Texas feedlot entrepreneurs would pay for scrub calves.)

There were square-jawed Malefoot relatives in New Brunswick and in Maine, they were all over Texas, Beaumont on the Gulf, up in the Big Thicket country through Basile Malefoot who had married into the Plemon Barko rednecks with their cur dogs and whooping coon hunts on a dirt-yard frontier, Basile who on horseback could round up unmarked pigs with his dogs, rope a young porker and haul it squealing up on the saddle, clip its ears and release it. A twirl of his rope, a cry, and he had another.

Basile’s older brother, Elmore Malefoot, herded cattle and raised hogs, fought Texas fever, ticks and flies on the north edge of the Calcasieu prairie near the pine flats where spits and points of woodland projected into the grassy flat plains like headlands and capes into the sea, where groves of hickories and oak and the small indentations of prairie, reminding the homesick of the irregularities of the lost coastline, were named coves and bays and islands. In the woods to the north of the prairies lived a strew of Scots Irish and Americans on their lonely square tracts, insulated from the pleasure of company and the comfort of good neighbors; the Germans down from the midwest to raise rice instead of wheat had been swallowed up, had gone French after a taste of bayou water.

The third brother, Onesiphore, had stayed in the small settlement of Goujon. Long, narrow strips of farmland ran out behind the houses as on the distant St. Lawrence centuries earlier. Onesiphore raised hogs and cane and grazed a few scrubby cattle on gazon, grass that grew lush and thick but failed to nourish and died and rotted when winter frost was followed by the inevitable rain. The state paved the old gumbo roads in the thirties and now, in 1959, people built along the macadam, no longer a mire of mud or choking dustland, as they had built once on the river, arranging the land in novel patterns.

Onesiphore Malefoot could remember his father, Andre, a man who always looked as though he were leaning back in a chair even when he was standing up, hauling their new-built house (constructed in Mermantau, near the sawmill), with teams of oxen and the help of his brothers, Elmore and Basile, over the open prairie.

“It took three days to get to Goujon. Oh yeah, they couldn’t get more than ten mile a day. That poor lovely man, he has the luck of a skinny calf. He get it move and what a trouble, he forget she’s jacked up and in the night—and he goes fall off the side of the house and break his leg.” The house was buried in four immense cape jasmines, the drugging, drowsing perfume of home for every Malefoot who ever lived within its walls, a missing sweetness that made Buddy uneasy when he was out on the rig doing his fourteen days, making good money and dying of homesickness.

“Tell me again about this accordeen thing and how you found it and what’s so good about it. Why you buy this? We got accordeens plenty, the Napoleon Gagne, the blue one, we got the Spanish three-row, and you, you got that pretty little Soprani, and we could get fixed up the funny one—I forget all them name, but the one I wish we got is that old black and gold Monarch. Oh yeah. We got now un mystere accordeen, is it?”

The daughter-in-law opened her mouth for the second time.

“Pete Lucien’s Marie got her niece Emma down from Maine, her husband Emil plays some music up there, the accordion—”

“Country, he plays country and western music. You know, ‘Saddle my yodelin bronco and ride through the campfire at night—’–Buddy gargled an imitation yodel. “What the hell they’re doin with that kind of music in Maine? You got a cigarette, Papa?”

“How about right here? Happy Fats, oh yeah, he ain’t influence by country-western? The Rayne-Bo Ramblers, Hackberrys? Diable, they was playin it when I was a bébé. How about Frank Deadline, after the war? I play it myself, oh yeah, western swing, you play it, what you play sounds pure country sometimes. Hell, country all you hear on the radio. You told me yourself country is all you get out on the rig. So this poor Emil, he plays country-western accordeen, come down here, listen some Louisiana music, he decide, oh yeah, give up his accordeen because he can’t never play so good as Cajuns?”

The daughter-in-law, wreathed in grey smoke, snickered. “Nothing like that.”

Buddy said, “nothing like that. He don’t like our music, too sad, not smooth. No, he keeps his own accordeen, just a big piano accordeen, white, weighs three or four tons, don’t make so much sound as a little ten-button. This one here is the accordeen of some other guy, married to the niece’s sister. The niece is Emma, her sister Marie, call Mitzi. The guy up in Maine, married to Marie, I forget his name, he’s the one that had the accordeen”—and he gestured at the case between his wife’s feet—“and he was crippled up bad, I don’t know it had ennathing to do with that accident Emma’s first husband died from, remember we heard about that?”

“Truckdriver-accident man the only one I heard about, oh yeah.”

“That’s him. Emma’s husband, first husband, before this Emil-with-the-accordion-to-sell that belongs to the friend of Emma’s truck-accident husband, the friend that marries Emma’s sister Marie call Mitzi and got bad hurt legs, I don’t know his name. That’s the songs they supposed to play up there, French songs about chain saws and log trucks. But no, they got to get cowboy hats. So this bad-leg friend of Emma’s truck-accident husband—he’s a friend of Emil too—it’s his accordeen, he’s in a wheelchair, he makes a promise to god, if he gets his legs better he’s gonna give up the accordeen. That’s what happen. He gets better. And then! He kills himself. Married two or three months and kill himself. So Emil and Emma is already on the road for down here to sell the accordeen for him, somebody down here will like to buy it. Now Marie, she’s the wife calls herself Mitzi, she’s Emma’s sister, of the bad-leg-wheelchair-friend-of-Emil-and-the-truck-accident-husband, she need every dollar.

“Ennaway, nobody up there like the button accordeen no more. Bad as here. They say it’s Frenchie stuff, so everybody going for the guitar, play rock and roll and all that. So I squeeze it a little bit, I can hear she’s special, Papa, you gonna like the sound of this instrument, and she’s got a big long bellows, plenty of squeeze in her, a crying voice. Oh she’s a nice little girl accordeen, lonesome for the pine trees in the north, for that poor dead man, she cries on her pillow all night.”

“Vite! Ála maison!I am on flames to hear this accordeen.”

“He scratch his name on the end, but I guess we sand it down right away. Leather bellows, tres bon kidskin, pliable. He put something on it, what they used to put on the harness of the log horses, this Emil says, so it don’t dry out.”

“It’s not stiff, it don’t fight you? Leather bellows fight back, oh yeah, they do. I remember one that Iry Lejeune had before he got run over—like squeezing a corpse.” He blew out a rod of smoke through pursed lips.

“No, it’s easy. She’s in pretty good shape, I think. You’ll look at it, Papa.”

Trois jours aprés ma mort

They were nearing the village now, past the gas station at the cross-roads.

“Wait, wait, wait, wait. What is this?” Onesiphore pointed at a building going up, the Marais brothers nailing up exterior sheathing, gaping rectangles in the facade for plate-glass windows.

“Gonna be a restaurant. Somebody from Houston behind it. Call it Boudou’s Cajun Café, jambalaya, crawfish boil and live music every night. For the tourists.”

“Who is this Boudou?”

“Nobody. They just make up a name it sounds like Cajun, French ennaway. Building up the tourist industry, employ local people, that’s the Marais brothers.”

“Y’know,” Onesiphore said, squinting up his eyes malevolently, “my generation we just live. We don’t think who we are, or anything, we just get born, live, fish and farm, eat home cooking, dance, play some music, grow old and die, nobody come here and bother us. Your generatio...