- 448 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

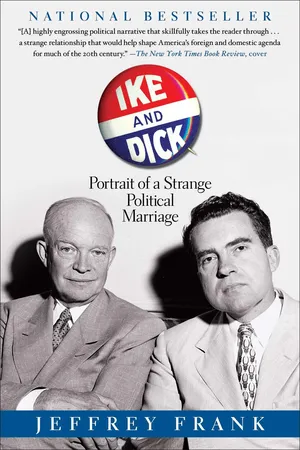

Dwight D. Eisenhower and Richard Nixon had a political and private relationship that lasted nearly twenty years, a tie that survived hurtful slights, tense misunderstandings, and the distance between them in age and temperament. Yet the two men brought out the best and worst in each other, and their association had important consequences for their respective presidencies.

In Ike and Dick, Jeffrey Frank rediscovers these two compelling figures with the sensitivity of a novelist and the discipline of a historian. He offers a fresh view of the younger Nixon as a striving tactician, as well as the ever more perplexing person that he became. He portrays Eisenhower, the legendary soldier, as a cold, even vain man with a warm smile whose sound instincts about war and peace far outpaced his understanding of the changes occurring in his own country.

Eisenhower and Nixon shared striking characteristics: high intelligence, cunning, and an aversion to confrontation, especially with each other. Ike and Dick, informed by dozens of interviews and deep archival research, traces the path of their relationship in a dangerous world of recurring crises as Nixon’s ambitions grew and Eisenhower was struck by a series of debilitating illnesses. And, as the 1968 election cycle approached and the war in Vietnam roiled the country, it shows why Eisenhower, mortally ill and despite his doubts, supported Nixon’s final attempt to win the White House, a change influenced by a family matter: his grandson David’s courtship of Nixon’s daughter Julie—teenagers in love who understood the political stakes of their union.

In Ike and Dick, Jeffrey Frank rediscovers these two compelling figures with the sensitivity of a novelist and the discipline of a historian. He offers a fresh view of the younger Nixon as a striving tactician, as well as the ever more perplexing person that he became. He portrays Eisenhower, the legendary soldier, as a cold, even vain man with a warm smile whose sound instincts about war and peace far outpaced his understanding of the changes occurring in his own country.

Eisenhower and Nixon shared striking characteristics: high intelligence, cunning, and an aversion to confrontation, especially with each other. Ike and Dick, informed by dozens of interviews and deep archival research, traces the path of their relationship in a dangerous world of recurring crises as Nixon’s ambitions grew and Eisenhower was struck by a series of debilitating illnesses. And, as the 1968 election cycle approached and the war in Vietnam roiled the country, it shows why Eisenhower, mortally ill and despite his doubts, supported Nixon’s final attempt to win the White House, a change influenced by a family matter: his grandson David’s courtship of Nixon’s daughter Julie—teenagers in love who understood the political stakes of their union.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Ike and Dick by Jeffrey Frank in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Historical Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

The Men’s Club

1

Herbert Hoover, the last living Republican president in mid-century America (his predecessor, Calvin Coolidge, died in 1933), treasured his membership in the Bohemian Club, which was founded in San Francisco in 1872 as a center of western influence and wealth. Hoover had joined in 1913 and for most of his life kept an eye out for recruits who might enliven the Bohemian Grove, the club’s summer encampment, 2,700 acres covered by redwoods and situated seventy miles north of San Francisco. The motto of the Bohemian members is the Shakespeare line “Weaving spiders come not here”—a warning to visitors to avoid self-promotion and networking—but for many guests and members the whole point of the Club was precisely that, and for them the Grove each summer was a natural habitat for web-weaving spiders. Hoover regarded his annual weeks at the Grove as “the greatest men’s party on earth.”

There are innumerable private clubs in America—city clubs and country clubs and Rotary Clubs and university clubs; General Eisenhower was familiar with many of them as part of his growing circle of wealthy, clubbable Americans. But the Bohemian Club is set apart by its rituals, its efforts at secrecy, and the exclusion of women as guests, although women eventually were permitted to work on the Grove’s grounds. In the 1950s, the club’s membership included bankers, politicians, influential journalists, and show business personalities like Edgar Bergen and Bing Crosby, and while the names changed, the traditions continued. Each year, as many as two thousand Bohemians and members and their guests still get together in the woods where they carry out the rites of the Grove: the serious and also somewhat vulgar entertainments (called High Jinks and Low Jinks), lectures (particularly the Lakeside Talks, during which prominent men give off-the-record speeches), and, most unforgettably, if only for its quasi-Masonic tendencies, the Cremation of Care ceremony, during which men in red hoods and red robes—some playing dirgelike music and others carrying torches—bear a mock coffin to a nearby lake, where a mock corpse that represents Dull Care is “cremated.” These private ceremonies have become less secret, and therefore perhaps less interesting, in the age of YouTube.

Richard Nixon stayed at the Grove in late July 1950, because Herbert Hoover, whom his associates and friends called the Chief (and who liked being called Chief), had taken a liking to him even before they’d met; he particularly admired Nixon’s work with the House Un-American Activities Committee. In January 1950, after Alger Hiss was found guilty of perjury (for lying about committing espionage, for which the statute of limitations had expired), Hoover wrote—“My dear Mr. Congressman”—to say that Hiss’s conviction “was due to your patience and persistence alone. At last the stream of treason that existed in our Government has been exposed in a fashion that all may believe.”

The Chief always gave a lot of thought to Cave Man Camp—Hoover’s camp, one of several dozen separate camps at the Grove, where he was known as the No. 1 Cave Man. He was particularly interested that year in bringing in Nixon as well as Conrad Hilton, the hotel man, and soon enough it was shaping up to be a first-rate Grove summer, all the more so because General Eisenhower, also paying his first visit, had accepted an invitation to give the Lakeside Talk. Eisenhower had turned down a number of earlier invitations, but Fred Gurley, the railroad man whom Ike had met two years before in Chicago, not only invited him to the Grove, but, as the president of the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe, was able to offer a superior means of transport.

• • •

By tradition, the speakers who “gave a Lakeside” did so at Cave Man Camp. These talks were sometimes regarded as a way to take the measure of a politician, and interest in Eisenhower in 1950 had a lot more to do with his political future than with his job as president of Columbia University or his career as a soldier, although the nation was at war again. This time it was in Korea, where the United States had become the major actor in a United Nations “police action.” At the camp lunch, Hoover, as he usually did, sat at the head of the table; Eisenhower was next to him on his right and Nixon was on his left, three seats down. As Nixon recalled the summer day when Eisenhower spoke, the general “was deferential to Hoover but not obsequious,” and “He responded to Hoover’s toast with a very gracious one of his own.” Nixon was sure that Ike knew he was in “enemy territory among this generally conservative group”; Hoover had become increasingly encrusted with conservative views since his defeat by FDR in 1932. When it came to the Republican Party’s nominee for president, most of Hoover’s friends—and the Chief himself—favored the candidate of the old guard, Robert Alphonso Taft, the Ohio senator, who had gone after the nomination before and would go after it again in 1952.

Although Nixon had seen Eisenhower again in 1948, walking in the funeral cortege for General John J. Pershing, he had never seen him close up, and he paid sharp attention. “It was not a polished speech, but he delivered it without notes and he had the good sense not to speak too long,” he recalled. “The only line that drew significant applause was his comment that he did not see why anyone who refused to sign a loyalty oath should have the right to teach at a state university.” After the talk, the attendees sat around a campfire and discussed what the general had said. “The feeling,” Nixon thought, “was that he had a long way to go before he would have the experience, the depth, and the understanding to be President.”

Nixon and Eisenhower talked briefly that day, a conversation that did not leave enough of an impression for Eisenhower ever to refer to it. Afterward, Eisenhower went by rail to Denver, where his mother-in-law lived and where he spent the next six weeks, while Nixon returned to his increasingly shrill senatorial campaign, which ended with him defeating Helen Douglas by a margin of more than 600,000 votes. Nixon was thirty-seven years old, and on election night Pat and Dick and some of their friends celebrated; they went from party to party, and when they came to a room with a piano, the senator-elect, an autodidactic pianist who played by ear and always in the key of G, would pound out “Happy Days Are Here Again,” not caring that Democrats liked that song, too. The victory, and the insistent focus on Communism during the campaign, gave Nixon a kind of national credential; it brought him into contact with movie stars like Dick Powell and Dennis Morgan and the politically engaged gossip columnist Hedda Hopper. (“Watch that boy! He’s presidential timber!” Hopper wrote when Nixon was a senator.) He got another note from the Chief, this one saying, “My dear Mr. Congressman: Your victory was the greatest good that can come to our country,” followed by an invitation: “My dear Senator Nixon: This is just by way of suggesting that if you ever come to New York, I will gladly produce food.” Those who had never liked Nixon very much began to look at him with something close to hatred.

2

Once in a while that fall, someone would mention General Eisenhower, who was back in Morningside Heights. Governor Dewey did so when he appeared on Meet the Press in mid-October and declared that he, personally, was through running for president. When a questioner asked, “Governor, if you are not going to run, do you have any candidates in mind?” Dewey replied, “Well, it’s a little early, but we have in New York a very great world figure, the president of Columbia University, one of the greatest soldiers of our history, a fine educator, a man who really understands the problems of the world, and if I should be re-elected governor and have influence with the New York delegation, I would recommend to them that they support General Eisenhower for president if he would accept the draft.” Dewey’s statement was not only an endorsement but a warning to the old guard that the eastern branch of the Republican Party was still around, that its internationalist principles remained unshaken, and that people like Dewey were prepared to fight for them.

At the end of 1950, Eisenhower, at President Truman’s request, took a leave of absence from Columbia to return to active duty, becoming the first Supreme Allied Commander Europe (SACEUR). In April 1951, he set up SHAPE, and in keeping with his reputation for modest living, turned down a chance to locate his office at the Palace of Fontainebleau, which the French had offered. He chose instead a prefabricated building fifteen miles from Paris. Europeans were impressed by Eisenhower. “He fascinates them as a heroic fictional character of a type they have never read about before—a non-Napoleonic, unmilitary-minded, professional general of high class,” Gênet (Janet Flanner) wrote in The New Yorker. “They think him humane, a tactician, a great soldier, an honest democrat.”

Eisenhower had mixed feelings about this move. He and Mamie had been enjoying life in Morningside Heights, though he once said that he never went out for a walk at night without carrying his service revolver. But he could not turn down a president—and this was an appealing request, not least because it kept him removed from the contagions of American politics, a subject that kept being broached not only by restless journalists but by visitors, especially a group of relatively new friends, well-to-do businessmen to whom he sometimes referred as “the gang.” This set included William Robinson, executive vice president of the New York Herald Tribune; Clifford Roberts, a partner in the investment banking firm Reynolds & Company and, perhaps more importantly, a cofounder (with the celebrated golfer Bobby Jones) of the Augusta National Golf Club; Ellis (Slats) Slater, the chairman of Frankfort Distilleries; and George E. Allen, an insurance executive and, for a few years, a commissioner of the District of Columbia, who was sort of an odd man out—he was not very wealthy and had been a friend of Harry Truman’s. But like the others, he enjoyed golf and bridge, and his wife, Mary, had been close to Mamie Eisenhower during the war. Not all the gang members were fond of each other; Cliff Roberts even tended to be jealous of his time with Eisenhower, almost as if he was in competition for the hand of a woman. Ike was probably most comfortable around Allen and a later arrival, Freeman Gosden, who belonged to the Augusta National and was known for his roles as the Kingfish and Amos on the radio version of Amos ’n’ Andy.

Like background noise, the chatter about Eisenhower as a presidential candidate got louder, so much so that there developed a hallucinatory view of Eisenhower’s place in the political scene—one that ascribed to him a spiritual affinity with both major political parties. At one point in the spring of 1951, Senator Paul Douglas of Illinois, a Democrat, suggested that if Truman didn’t run again and the Republicans chose Eisenhower, Democrats should go ahead and nominate him, too. Douglas pointed out that the two parties could still distinguish themselves by selecting different vice presidential candidates. Eisenhower was not immune to that sort of improbable idea. “You don’t suppose a man could ever be nominated by both parties, do you?” he once asked Walter Lippmann. Richard Nixon, who was as aware as anyone of all the interest in Ike, saw the general for a second time when he visited SHAPE headquarters in May. The stopover was a detour on what had started as a trip by an American delegation to the new World Health Organization in Geneva. For Nixon, it was an opportunity to have a conversation with the general nearly a year after their inconsequential chat at the Bohemian Grove. For Eisenhower, it was a chance to get briefed on a domestic concern—the purported peril from homegrown subversives. After all, who was better equipped to fill him in on the Red threat than the man who had bagged Alger Hiss? Their meeting came about through the intervention of Alfred Kohlberg, a rich textile importer (one journalist described him as a “round, bald little man with snapping brown eyes”), who was one of America’s most active anti-Communists, a believer in the “someone-lost-China” theory of history—and someone with a seemingly unlimited supply of unfounded suspicions.

On May 1, 1951, Kohlberg, who also had an overactive busybody side, wrote to Nixon, saying, a little mysteriously, that “General Eisenhower feels a need for more information about the communist conspiracy. There are two men with whom he would like to talk on this. You are one of them.” For some reason, Kohlberg did not reveal the identity of the second man and felt it necessary to add that “The friend of the General’s who spoke to me is not acquainted with either you or the other man.” In any case, on May 9, 1951, a message from DEPTAR (the Department of the Army) arrived at SACEUR reporting that Senator Nixon was on his way, and SACEUR then told DEPTAR that they were holding open May 18, at ten-thirty in the morning. Nixon later told Kohlberg that he’d spent an hour with the general and “incidentally, was very impressed with his understanding of the nature of the problems we face both abroad and at home in respect to the Communist conspiracy.” All in all, Nixon after seeing Eisenhower came away in much the same frame of mind as when he’d left the Bohemian Grove, and he later recalled the meeting in some detail: Eisenhower “was erect and vital and impeccably tailored, wearing his famous waist-length uniform jacket, popularly known as the ‘Eisenhower jacket.’ . . . He spoke optimistically about the prospects for European recovery and development,” a subject in which Nixon remained interested. “What we need over here and what we need in the States is more optimism in order to combat the defeatist attitude that too many people seem to have,” Eisenhower said. They didn’t discuss American politics—as Nixon saw it, they stepped cautiously around that topic—but Nixon noted that “it was clear he had done his homework,” which included knowing something about Senator Nixon.

Rather than staying behind a desk, the general invited Nixon to sit on a couch beside him, and went on to tell him that he’d read about the Hiss case in Seeds of Treason and that “The thing that most impressed me was that you not only got Hiss, but you got him fairly.” Nixon was proud of that compliment and found the visit memorable enough to enter some thoughts in the Congressional Record, which was the first public juxtaposition of their names: “I was impressed, let me say parenthetically, with the excellent job he is doing against monumental odds, in the position he holds,” Nixon said, adding that Eisenhower had told him that “one of the greatest tasks” he had was to convince America’s allies “of the necessity for deferring . . . expenditures for nonmilitary purposes and for all those countries to place the primary emphasis in their budgets upon the necessity of rebuilding their armed forces to meet the threat of Communist aggression.” Years later, Nixon had a distinctly different recollection, recalling an Eisenhower observation that “being strong militarily just isn’t enough in the kind of battle we are fighting now”—struck by that because “then as now it was unusual to hear a military man emphasize the importance of non-military strength.” Very likely, Ike said both things; and very likely Nixon adapted each message to the times—the peak of the Cold War and the arrival of détente—in which he lived.

For Nixon, paying this call was a way to make an impression on someone who might one day be a national leader as well as a chance to let the general know that they were two men of one mind on the issues of the day. “I felt that I was in the presence of a genuine statesman,” Nixon recalled, “and I came away convinced that he should be the next President. I also decided that if he ran for the nomination I would do everything I could to help him get it.”

• • •

By the fall of 1951, columnists and poll takers had decided that there were two major Republican candidates: the declared Senator Taft and the undeclared General Eisenhower. The general already had a wide following in the press, starting with the Herald Tribune, the magnetic pole of eastern Republicanism, as well as the Luce publications: Time, Life, and Fortune. Henry Robinson Luce, Time’s founder, was dazzled by the general. “Harry fell in love with Eisenhower as people fall in love with beautiful girls,” Allen Grover, a former Time vice president and Luce’s personal aide, told one biographer. “Here was this marvelous man who came from the heartland of America, the fair-haired boy, the leader of the great armada of World War II, a crusader, honest and straight!” (Luce’s wife, Clare Boothe Luce, the charming and slightly mad former Connecticut congresswoman—Cecil Beaton supposedly described her as “drenchingly beautiful”—saw Eisenhower in the fall of 1949 to discuss, as he put it, “the future of the c...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Dedication

- Prologue

- Chapter 1: The Men’s Club

- Chapter 2: The Ticket

- Chapter 3: The Silent Treatment

- Chapter 4: “The Greatest Moment of My Life”

- Chapter 5: President Eisenhower

- Chapter 6: Diplomatic Vistas

- Chapter 7: The Troublesome Senator

- Chapter 8: “Mr. Nixon’s War”

- Chapter 9: The Pounding

- Chapter 10: Mortal Man

- Chapter 11: Survivor

- Chapter 12: The Liberation of Richard Nixon

- Chapter 13: “Once an Oppressed People Rise”

- Chapter 14: Worn Down

- Chapter 15: Should He Resign?

- Chapter 16: Dirty Work

- Chapter 17: Unstoppable

- Chapter 18: “If You Give Me a Week, I Might Think of One”

- Chapter 19: The Good Life

- Chapter 20: The Obituary Writers

- Chapter 21: Easterners

- Chapter 22: The “Moratorium”

- Chapter 23: Private Agendas

- Chapter 24: The Rehearsal

- Chapter 25: “That Job Is So Big, the Forces Are So Great”

- Chapter 26: David and Julie

- Chapter 27: Family Ties

- Chapter 28: A Soldier’s Serenade

- Chapter 29: Victory Laps

- Chapter 30: Eulogies

- Chapter 31: What Happened Next

- Photographs

- Acknowledgments

- About Jeffrey Frank

- Notes

- Sources

- Index

- Copyright