![]()

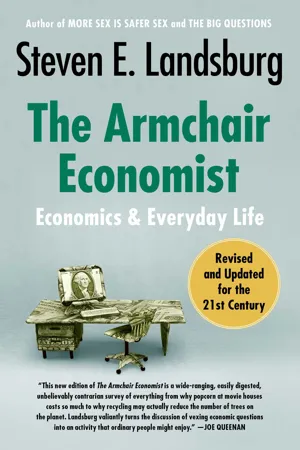

IN THIS REVISED AND UPDATED EDITION of Steven Landsburg’s hugely popular book, he applies economic theory to today’s most pressing concerns, answering a diverse range of daring questions, such as:

Why are seat belts deadly? • Why do celebrity endorsements sell products? • Why are failed executives paid so much? • Who should bear the cost of oil spills? • Do government deficits matter? • How is workplace safety bad for workers? • What’s wrong with the local foods movement? • Which rich people can’t be taxed? • Why is rising unemployment sometimes good? • Why do women pay more at the dry cleaner? • Why is life full of disappointments?

Whether these are nagging questions you’ve always had, or ones you never even thought to ask, this new edition of The Armchair Economist turns the eternal ideas of economic theory into concrete answers that you can use to navigate the challenges of contemporary life.

![]()

PRAISE FOR THE ARMCHAIR ECONOMIST

“A wonderful little book. . . . Landsburg presents fascinating concepts in a form easily accessible to noneconomists.”

—Erik M. Jensen, Cleveland Plain Dealer

“Enormous fun from its opening page. . . . Landsburg has done something extra-ordinary: He has expounded basic economic principles with wit and verve.”

—Dan Seligman, Fortune

“An ingenious and highly original presentation of some central principles of economics for the proverbial Everyman. Its breezy tone conceals the subtlety of the analysis. Guaranteed to puncture some illusions and to make you think.”

—Milton Friedman

![]()

STEVEN E. LANDSBURG is a professor of economics at the University of Rochester. He is the author of

Fair Play, More Sex Is Safer Sex, The Big Questions, two textbooks on economics, a textbook on general relativity and cosmology, and more than thirty journal articles on mathematics, economics, and philosophy. For more than ten years he wrote the monthly Everyday Economics column in

Slate magazine. He has written regularly for

Forbes and occasionally for the

New York Times, the

Wall Street Journal, and the

Washington Post. He blogs at

www.TheBigQuestions.com.

MEET THE AUTHORS, WATCH VIDEOS AND MORE AT

SimonandSchuster.com

THE SOURCE FOR READING GROUPS

COVER DESIGN BY ERIC FUENTECILLA • COVER PHOTOGRAPH BY BRUCE MARTIN/PHOTOGRAPHER’S CHOICE/GETTY IMAGES

![]()

![]()

Thank you for purchasing this Free Press eBook.

Sign up for our newsletter and receive special offers, access to bonus content, and info on the latest new releases and other great eBooks from Scribner and Simon & Schuster.

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

![]()

![]()

Free Press

A Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

Copyright © 1993, 2012 by Steven E. Landsburg

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information address Free Press Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020

First Free Press trade paperback edition May 2012

FREE PRESS and colophon are trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact Simon & Schuster Special Sales at 1-866-506-1949 or

[email protected].

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event. For more information or to book an event contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at 1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at www.simonspeakers.com.

Designed by Jill Putorti

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Landsburg, Steven E.

The armchair economist: economics and everyday life / Steven E. Landsburg.––1st pbk., rev. & updated ed.

p. cm.

1. Economics––Sociological aspects. I. Title.

HM35.L35 2012

306.3––dc23 2011051923

ISBN 978-0-02-917775-4

ISBN 978-1-4516-5173-7 (pbk)

ISBN 978-1-4165-8725-5 (ebook)

![]()

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Preface to the Second Edition vii

Introduction xi

I. What Life Is All About

1. The Power of Incentives: How Seat Belts Kill

2. Rational Riddles: Why U2 Concerts Sell Out

3. Truth or Consequences: How to Split a Check

or Choose a Movie

4. The Indifference Principle: Who Cares If the

Air Is Clean?

5. The Computer Game of Life: Learning What It’s

All About

II. Good and Evil

6. Telling Right from Wrong: The Pitfalls of Democracy

7. Why Taxes Are Bad: The Logic of Efficiency

8. Why Prices Are Good: Smith versus Darwin

9. Of Medicine and Candy, Trains and Sparks:

Economics in the Courtroom

III. How to Read the News

10. Choosing Sides in the Drug War:

How the Atlantic Monthly Got It Wrong

11. The Mythology of Deficits

12. Unsound and Furious: Spurious Wisdom

from the Media

13. How Statistics Lie: Unemployment Can Be Good

for You

14. The Policy Vice: Do We Need More Illiterates?

15. Some Modest Proposals: The End of Bipartisanship

IV. How Markets Work

16. Why Popcorn Costs More at the Movies: And Why the Obvious Answer Is Wrong

17. Courtship and Collusion: The Mating Game

18. Cursed Winners and Glum Losers: Why Life Is Full

of Disappointments

19. Random Walks and Stock Market Prices:

A Primer for Investors

20. Ideas of Interest: Armchair Forecasting

21. The Iowa Car Crop

V. The Pitfalls of Science

22. Was Einstein Credible? The Economics

of the Scientific Method

23. New Improved Football: How Economists Go Wrong

VI. The Pitfalls of Religion

24. Why I Am Not an Environmentalist: The Science

of Economics versus the Religion of Ecology

Appendix: Notes on Sources

Index

About the Author

Endnotes

![]()

PREFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION

One day in 1991, I walked into a medium-size bookstore and counted over 80 titles on quantum physics and the history of the universe. A few shelves over I found Richard Dawkins’s bestseller The Selfish Gene, along with dozens of others explaining Darwinian evolution and the genetic code.

In the best of these books, I discovered natural wonders, confronted mysteries, learned new ways of thinking, and felt I had shared in a great intellectual adventure founded on ideas that are dazzling in their scope and their simplicity.

Economics too is a great intellectual adventure, but in 1991 I could find not a single book that proposed to share that adventure with the general public. There was nothing that revealed the economist’s unique way of thinking, using a few simple ideas to illuminate the whole range of human behavior, shake up our preconceptions, and jolt us into new ways of seeing the world.

I resolved to write that book. The Armchair Economist was published in 1993 and attracted a large and devoted following. In the intervening 20 years, it has earned much high praise. But what I take most pride in is that The Armchair Economist is still widely recognized among economists as the book to give your mother when she wants to understand what you do all day.

A lot has changed in that 20 years. Today no bookstore patron could complain about a paucity of titles in the popular economics section. Some of the new titles are quite good. Several, I daresay, were inspired by Armchair. The most well-known of the recent titles is Levitt and Dubner’s Freakonomics, which I think is a rollicking good read (and I said so when I reviewed it for the Wall Street Journal ). But for all its merits, Freakonomics is more a collection of wonderful and enlightening anecdotes than a guide to understanding economics. Freakonomics is out to dazzle you with facts; The Armchair Economist is out to dazzle you with logic.

Logic matters. It leads us from simple ideas to surprising conclusions. A simple idea is that people respond to incentives. A surprising conclusion is that when drivers are protected by air bags, they drive more recklessly and have more accidents. A simple idea is that when the price of something goes down, suppliers provide less of it. A surprising conclusion is that recycling programs, which reduce the price of timber, ensure that fewer trees are planted and forests shrink. A simple idea is that monopolists charge whatever price the market will bear for their output. A surprising conclusion is that when oil supplies are interrupted, steep price hikes are evidence of competition, not monopoly; a monopoly oil company wouldn’t wait for a supply interruption to raise the price.

Evidence matters too, but logic can be powerful all on its own. Take, for example, the argument about recycling and the size of forests. If I wrote that the reason we have large cattle herds in this country is that people eat a lot of meat, few readers would demand detailed numerical evidence to support that conclusion. The idea itself is too powerful and too compelling. It’s instructive, then, to realize that the same powerful and compelling idea tells us that one reason we have large cultivated forests is that people use a lot of paper. Of course, ideas can always be misleading—but then so can numbers. Still, we advance by learning new ways to think, even if those ways are not infallible.

Much else has changed since 1991. When I wrote The Armchair Economist, I envisioned a “computer game of life,” where nobody ever tells you whether you won or lost. You live and you die, and if you play well you collect rewards. If you decide it’s not worth the trouble to play well, that’s fine too. Today that game exists, and over 20 million people have played it. It’s called Second Life. In 1991, when I wanted an example of a crazy entrepreneurial wild goose chase, I invented a story about a CEO who wanted to build a computer you could carry in your pocket. Perhaps you’re now reading these words on that computer.

There’s also much that hasn’t changed. The basic principles of economics continue to surprise, delight, and edify, and they’re much the same as they were in 1991, though there are always new applications.

In updating The Armchair Economist for the 21st century, I’ve culled the Internet, the media, and my own experience of life for good contemporary applications of the eternal ideas of economic theory. As a result, some chapters—those where...