- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

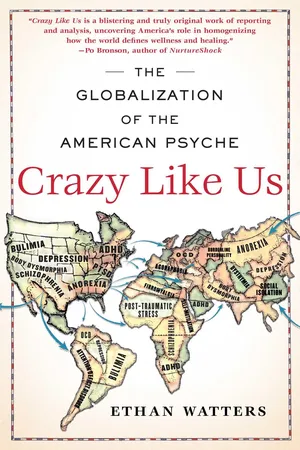

“A blistering and truly original work of reporting and analysis, uncovering America’s role in homogenizing how the world defines wellness and healing” (Po Bronson).

In Crazy Like Us, Ethan Watters reveals that the most devastating consequence of the spread of American culture has not been our golden arches or our bomb craters but our bulldozing of the human psyche itself: We are in the process of homogenizing the way the world goes mad.

It is well known that American culture is a dominant force at home and abroad; our exportation of everything from movies to junk food is a well-documented phenomenon. But is it possible America's most troubling impact on the globalizing world has yet to be accounted for?

American-style depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and anorexia have begun to spread around the world like contagions, and the virus is us. Traveling from Hong Kong to Sri Lanka to Zanzibar to Japan, acclaimed journalist Ethan Watters witnesses firsthand how Western healers often steamroll indigenous expressions of mental health and madness and replace them with our own. In teaching the rest of the world to think like us, we have been homogenizing the way the world goes mad.

In Crazy Like Us, Ethan Watters reveals that the most devastating consequence of the spread of American culture has not been our golden arches or our bomb craters but our bulldozing of the human psyche itself: We are in the process of homogenizing the way the world goes mad.

It is well known that American culture is a dominant force at home and abroad; our exportation of everything from movies to junk food is a well-documented phenomenon. But is it possible America's most troubling impact on the globalizing world has yet to be accounted for?

American-style depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and anorexia have begun to spread around the world like contagions, and the virus is us. Traveling from Hong Kong to Sri Lanka to Zanzibar to Japan, acclaimed journalist Ethan Watters witnesses firsthand how Western healers often steamroll indigenous expressions of mental health and madness and replace them with our own. In teaching the rest of the world to think like us, we have been homogenizing the way the world goes mad.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Crazy Like Us by Ethan Watters in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychologie & Internationale Beziehungen. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

PsychologieSubtopic

Internationale Beziehungen1

The Rise of Anorexia in Hong Kong

Psychiatric theory cannot deny its participation in the social trajectory of the anorectic discourse, which articulates personal miseries as much as it does public concerns.

SING LEE

On the morning of my visit to Dr. Sing Lee, China’s preeminent researcher on eating disorders, I took the subway a few stops north of downtown Hong Kong to the Prince of Wales Hospital in the suburb of Shatin. In the clean and well-lit subway corridors, I passed several large posters featuring outlandishly slender, bikinied young women promoting a variety of health care regimens, cellulite-removing creams, and appetite-suppressant supplements. The advertisements over the handrails in the subway cars repeated the offers. The magazines and newspapers being read by the commuters were filled with similar pitches, often featuring before and after photos, young women becoming little more than skin and bones after the offered treatment. Such products are a huge business in Hong Kong and increasingly in mainland China. Over the past few years the beauty industry in Hong Kong (including dieting, cosmetics, skin care, and fitness) has outspent every other business sector on advertising. In that week’s issue of the popular weekly magazine Next, a remarkable 110 of the publication’s 150 ads were for slimming or beauty products and services.

The reporting and photojournalism that appeared alongside those ads had a slightly different obsession: telling tales of young women celebrities. That morning’s Standard, one of Hong Kong’s English dailies, prominently reported the recent misadventures of several famous young women, including Britney Spears, who had that week been held against her will at the UCLA Medical Center. She had been “5150ed,” which is the code for a California statute that allows doctors to hold a patient involuntarily if she is deemed a danger to herself or others. On the opposing page was an article about the Japanese pop idol Kumi Koda, who lost her job as a spokesmodel for Japan’s third largest cosmetics company, Kose Corp., after making pejorative comments about the fertility of older women. The cute and perky 25-year-old had gone on a popular radio show and given her medical opinion that a “mother’s amniotic fluid turns rotten once a woman reaches about thirty-five… It gets dirty.”

The biggest story in The Standard, in fact the front-page story in every paper in Hong Kong that morning, was a sex scandal involving a handful of the region’s best-known female pop stars and a young actor. Hundreds of very explicit nude photos had been posted on the Internet of singer Gillian Chung and actresses Bobo Chen and Cecilia Cheung Pak-chi, among a dozen others. That same week a humanitarian crisis was erupting along the Gaza-Egyptian border and a severe snowstorm was sweeping across much of eastern China, threatening to strand millions of holiday travelers, yet no other story could compete with this sex scandal. Everyone, from politicians to op-ed writers, felt the need to criticize the behavior of the young women. Even Hong Kong’s Catholic bishop John Tong weighed in on the subject of celebrity sin and cyber etiquette, saying that it was important to “keep our minds decent” and “not post or circulate these pictures.”

Of course it’s not possible to say exactly what these advertisements, images, and stories of celebrity misadventures might have been adding up to in the minds of average adolescent girls in Hong Kong. It didn’t take much reading between the lines, however, to perceive a high degree of confusion and ambivalence surrounding the issues of female body image, sexuality, youth, beauty, and aging. Young women in some contexts were worshipped for their attractiveness, while in other situations they were humiliated and publicly vilified with a vitriol that would be hard to overstate. Whatever understanding Hong Kong teenage girls were piecing together about the postadolescent world from these sources, it is safe to say that it was not unconflicted.

Given this environment, it would make sense to most Americans and Europeans that occurrences of anorexia and bulimia have spiked here in the past fifteen years. Nor would it likely be a surprise that Gillian Chung, one of those young celebrities in the sex scandal, had herself battled bulimia. Most well-educated Westerners understand that anorexia is sparked by cultural cues, but they often have a fairly narrow conception of what those cues might be. Most assume that anorexia, with its attendant fear of fatness and body dysmorphic disorder, is born of a peculiar modern fixation with a slender, female body type, and that popular culture transmits this fetish to young women. As we’ve exported our obsessions with slender models—our Barbie dolls and our Kate Moss fashions—it makes sense to us that eating disorders have followed in their wake.

But although this commonsense cause and effect might be part of the story, Sing Lee’s research shows that there have been other, more subtle, cross-cultural forces at work here. The full story of how anorexia spread from the American suburbs to Hong Kong is more complex and, in many ways, more troubling. It turns out that the West may indeed be culpable for the rise in eating disorders in Asia, but not for the obvious reasons.

After making my way across Shatin, I found Lee’s small suite of offices among the labyrinth of midrise buildings that make up the Prince of Wales Hospital. Introduced by his assistant, Dr. Lee was younger than I expected. At 49 years old, he’s had a remarkable output as a scholar despite the fact that he has split his time between seeing patients at the public hospital, teaching, and running a mood disorders center. He admits that at times he has been accused of being a workaholic. “I do work long hours, but I’ve never experienced much work stress,” he said to me in what I would come to know as his characteristic humble manner. “I’ve wanted to be a psychiatrist since high school and I still love the work of meeting patients and writing about ideas.” Given the amount of time he spends in his office, he’s allowed himself to build a comfortable environment. The place has the feel of a stylish bachelor pad. The bucket seat and gearshift of a sports car sat on the floor next to the couch. Directly across from his desk was one of his prized possessions: an antique vacuum tube stereo connected to two imposingly large speakers. The tuner was made in the early 1960s and at the time cost as much as a VW Beetle and requires vacuum tubes the size of small lightbulbs to operate. For a true classical music audiophile such as Lee, however, there is no substitute for the resonant tones it produces.

Even after two decades of charting the cultural currents that have brought the American version of anorexia to these shores, Lee remains passionately interested in talking about the puzzle. He was the first scholar to document anorexia in Chinese women. The remarkable thing he found was that before the illness was well known in the province, Chinese anorexia was unlike that found in the West. These atypical anorexics, as he calls them, displayed a different cluster of symptoms than their Western counterparts. Most, for instance, did not display the classic fear of fatness common among Western anorexics, nor did they misperceive the frail state of their body by believing they were overweight. It was while he was trying to puzzle out these differences that he witnessed something remarkable.

Over a short period of time the presentation of anorexia in Hong Kong changed. The symptom cluster that was unique to his Hong Kong patients began to disappear. What was once a rare disorder was replaced by an American version of the disease that became much more widespread. Understanding the forces behind that change may not only explain why anorexia became common in Hong Kong, but it may also lead us to reconsider the momentum behind the disease in the West.

The Death of a Patient

When Sing Lee came back to Hong Kong from his training in England in the mid-1980s, he took a job at the Prince of Wales Hospital and began looking for Chinese anorexics. Having been introduced to the disorder while in England he was, like many young psychiatrists, fascinated by the fundamental conundrum of the disease: Why would healthy young women with plenty of resources starve themselves?

At the time Lee began his search, the long-held belief that eating disorders were confined to American and Western European populations was just beginning to show cracks. Even though prominent eating disorder researchers were making the argument as late as 1985 that anorexia didn’t exist outside of the United States, cases were beginning to show up in Russia and Eastern Europe. Although it was still believed to be rare in Latin American countries, researchers and clinicians also began discovering young women with anorexia in Japan and South Korea.

In China and Hong Kong the disorder remained all but unknown. Searching the two major psychiatric journals published in China, Lee found not a single paper documenting a Chinese woman with anorexia. With little to go on, he got to work searching the databases at the Prince of Wales Hospital. After an exhaustive search, he managed to identify just ten possible cases in the five years from 1983 to 1988. Given the thousands of patients seen at the hospital, he determined that anorexia was an exceedingly rare disorder in Hong Kong. His first paper on the topic, published in 1989 in the British Journal of Psychiatry, was titled “Anorexia Nervosa in Hong Kong: Why Not More in Chinese?”

The low rate of anorexia was a mystery that Lee wanted to figure out. Perhaps Chinese cultural beliefs or practices contained protective mechanisms. He knew, for instance, that historically there was little Chinese stigma surrounding larger body shapes. In fact popular Chinese sayings suggested that “being able to eat is to have luck,” “gaining weight means good fortune,” and “fat people have more luck.” He also considered that the later onset of puberty in Chinese girls compared to girls in the West might be a preventive factor. The physical changes that come with puberty might be less psychologically stressful when experienced with an added year or two of emotional maturity.

But even taking these differences into account, Lee couldn’t quite understand why the behavior was so uncommon among local adolescents. In many ways Hong Kong seemed primed for the disorder. It was a modern region that, thanks to years of British rule, had incorporated many Western values as well as styles of dress and eating. There were fast-food restaurants and health clubs. Thin Western and Chinese celebrities were idolized. It was a patriarchal culture, in which parents and teachers put intense pressure on students to compete. The Chinese obsession with food and the layered meanings of sharing meals within a family should have made food refusal a dangerously attractive behavior for an adolescent looking to send a distress signal to those around her.

All the triggers for anorexia that had been identified in Western literature seemed to be present in full force, and yet eating disorders remained rare. Lee suspected that there was something else, some factor that hadn’t been fully considered in the Western literature, that remained absent in Hong Kong. What that factor might be he could only guess.

Treating the few cases he could find, Lee discovered another puzzle. He noticed that the women who starved themselves in Hong Kong were different from the anorexics he had studied while training in England. The variations were sometimes so pronounced he wondered if he was seeing the same disease. To illustrate those differences, Lee recounted to me the story of one of the first patients he personally treated, a 31-year-old saleswoman I’ll call Jiao.

Lee still clearly remembers the first time he met Jiao in a hospital examination room in 1988. Although he knew from his research how thin anorexic patients could become, he couldn’t help but be taken aback at the sight of her. “She was shockingly emaciated—virtually a skeleton,” he recalls. “She had sunken eyes, hollow cheeks and pale, cold skin.” She was alert but uncommunicative. At 5 feet 3 inches, her ideal body weight should have been in the neighborhood of 110 pounds. Indeed, she had been that weight four years earlier, before she began to waste away. By the time she sought medical treatment she weighed just 48 pounds.

During his physical exam of Jiao, Lee noted that she had dry skin and a subnormal body temperature. More concerning, her blood pressure was low and her heartbeat was a plodding 60 beats per minute. He took X-rays after giving her a drink laced with barium so he could examine her esophagus. He also used an endoscope to examine her upper gastrointestinal system for blockages or lesions. Convinced the disorder wasn’t organic in origin, he began to piece together her personal history.

Jiao was the youngest child of three living children (two of her brothers died soon after birth). She had grown up in a working-class family in a rural village near Hong Kong, where she still lived. Like many in the Hong Kong area, her family was both emotionally enmeshed and yet physically disjointed. To earn a living, her father had lived apart from the family for many years at a time, and yet, when he was present, he demanded the absolute loyalty he felt was his traditional due as head of the household. During his visits home he often berated Jiao and her mother for small infractions, such as interrupting him when he spoke, and he freely expressed his disappointment that Jiao had not performed better in school. Her mother was a traditional housewife who was subservient to her husband and was socially isolated because she spoke only a Chinese dialect called Hakka. Although it was not a happy home, there was no history of mental illness, sexual or physical abuse, or eating disorders.

Jiao’s struggles with eating had begun in earnest four years earlier, in 1984, when her boyfriend deserted her by emigrating to England. She was devastated by his departure and began to refuse food and skip meals. Explaining her change in eating patterns to her family, she complained of pain and discomfort in her abdomen. During this time she became increasingly socially withdrawn and lost her job. Over those first years of the illness she saw various doctors. She was encouraged by health professionals as well as her family to eat more. Nevertheless she steadily lost weight year after year.

While relating her personal history to Lee during that first interview, Jiao cried at times but for the most part just looked sad and tired.

“What do you think is your main problem?” Lee finally asked her.

“Abdominal fullness and thinness,” she replied.

“What else?”

“A bad mood, it’s hard to describe.… It is no use talking about it anymore,” she said and began to weep.

“Is there a name for your condition?” Lee asked her.

“I don’t know,” she said. “Can you tell me what kind of disease it is?”

Lee had her draw a picture of herself. This technique is often used to assess whether anorexic patients have a distorted perception of their emaciated condition. The stick figure sketch she handed back to Lee, however, closely matched her skeletal condition.

Jiao’s presentation left Lee in a quandary. On the one hand, she was clearly starving herself to the point of death. On the other hand, she didn’t fit many of the American diagnostic criteria for anorexia. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, published by the American Psychiatric Association—the third edition released in the late 1980s had quickly become the worldwide standard—stated that someone suffering from anorexia not only rigidly maintains an abnormally low body weight but expresses an “intense fear of becoming obese, even when underweight,” and has a disturbed self-image, such as claiming to “feel fat when emaciated.”

But Jiao did not express a fear of being overweight. In addition, she didn’t have any misperception about the emaciated condition of her body. She described herself pretty much exactly as Lee saw her: as a very sick and dangerously thin young woman.

When he gave her the standard eating disorder questionnaire of the time, it also showed clear differences from what one would expect of an anorexic in the West. For instance, Jiao insisted that she never consciously restricted the amount of food she ate. Western anorexics, he knew, usually admitted to obsessing over food portions and quantities. When asked why she often went for whole days without eating, Jiao would say only that she felt no hunger and, pointing to the left side of her abdomen, describe how her stomach often felt distended.

These deviations from the Western diagnosis weren’t unique to Jiao. Most of the Hong Kong anorexics Lee was able to interview or treat around this time similarly denied any fear of being fat or of intending to lose weight to become more attractive. They often spoke of their desire to get back to a normal body weight. When explaining their refusal to eat, they most often ascribed the behavior to physical causes such as bloating, blockages in their throat or digestion, or the feeling of fullness in their stomach and abdomen. Their often repeated claim that they had no appetite also ran counter to conceptions of the disease put forward by Western experts. Psychiatrist Hilde Bruch, who wrote one of the seminal books on anorexia, The Golden Cage, asserted that “patients with anorexia nervosa do not suffer from loss of appetite; on the contrary, they are frantically preoccupied with food and eating. In this sense they resemble other starving people.”

As a group, these Hong Kong anorexics were different from their American counterparts in other ways as well. These were not the “golden girls” described in Western literature on eating disorders. Anorexia in the West was known to afflict well-to-do, popular, and promising young women who were sometimes perfectionists in other parts of their lives, such as school or sports. But Lee’s patients were often from poor families and among the lower achievers in their schools. They also did not give any hint of the moral superiority sometimes observed in Western anorexics.

Most curiously, they were often from outlying villages, not a population that Lee suspected would be most influenced by the globalization of Western pop culture. They had not begun their self-starvation after reading diet books or engaging in the exercise fads of the day. His atypical anorexics were not among the young women in Hong Kong adopting Flashdance fashions or going to Jazzercise classes. If Western pop cultural influences were at the heart of this disorder, there were certainly populations in Hong Kong who should have been harder hit. Hong Kong was, and remains, the most international of cities, and there were plenty of groups of adolescents and young women fully engaging in Western fashion and pop culture. But Lee’s patients did not come from these jet-setting subcultures.

While Lee had great respect for the clinical knowledge he had gained during his training in the West, he knew it posed a challenge as well. With the DSM becoming the world’s diagnostic manual for mental illness, it was easy to gloss over different disease presentations to make them fit the Western standard. But Lee was convinced that the distinctions between the American presentation of anorexia and what he was witnessing in Hong Kong was a meaningful difference that could lead to new insights into the disorder. He knew that if he was going to understand what was happening with his Hong Kong patients, he was going to have to get to the bottom of those differences.

Yin, Yang, and Qi

Despite Lee’s uncertainty about the diagnosis of anorexia, Jiao was clearly in need of immediate attention. With Lee’s encouragement she checked into the hospital, but she proved to be a difficult patient. She us...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Contents

- Introduction

- 1: The Rise of Anorexia in Hong Kong

- 2: The Wave That Brought PTSD to Sri Lanka

- 3: The Shifting Mask of Schizophrenia in Zanzibar

- 4: The Mega-Marketing of Depression in Japan

- Conclusion :The Global Economic Crisis and the Future of Mental Illness

- Sources

- Acknowledgments

- Index