eBook - ePub

How to Break a Terrorist

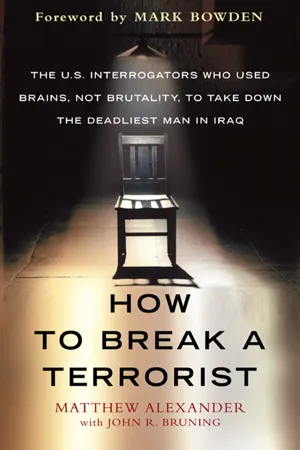

The U.S. Interrogators Who Used Brains, Not Brutality, to Take Down the Deadliest Man in Iraq

- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

How to Break a Terrorist

The U.S. Interrogators Who Used Brains, Not Brutality, to Take Down the Deadliest Man in Iraq

About this book

Finding Abu Musab al Zarqawi, the leader of Al Qaeda in Iraq, had long been the U.S. military's top priority -- trumping even the search for Osama bin Laden. No brutality was spared in trying to squeeze intelligence from Zarqawi's suspected associates. But these "force on force" techniques yielded exactly nothing, and, in the wake of the Abu Ghraib scandal, the military rushed a new breed of interrogator to Iraq.

Matthew Alexander, a former criminal investigator and head of a handpicked interrogation team, gives us the first inside look at the U.S. military's attempt at more civilized interrogation techniques -- and their astounding success. The intelligence coup that enabled the June 7, 2006, air strike onZarqawi's rural safe house was the result of several keenly strategized interrogations, none of which involved torture or even "control" tactics.

Matthew and his team decided instead to get to know their opponents. Who were these monsters? Who were they working for? What were they trying to protect? Every day the "'gators" matched wits with a rogues' gallery of suspects brought in by Special Forces ("door kickers"): egomaniacs, bloodthirsty adolescents, opportunistic stereo repairmen, Sunni clerics horrified by the sectarian bloodbath, Al Qaeda fanatics, and good people in the wrong place at the wrong time. With most prisoners, negotiation was possible and psychological manipulation stunningly effective. But Matthew's commitment to cracking the case with these methods sometimes isolated his superiors and put his own career at risk.

This account is an unputdownable thriller -- more of a psychological suspense story than a war memoir. And indeed, the story reaches far past the current conflict in Iraq with a reminder that we don't have to become our enemy to defeat him. Matthew Alexander and his ilk, subtle enough and flexible enough to adapt to the challenges of modern, asymmetrical warfare, have proved to be our best weapons against terrorists all over the world.

Matthew Alexander, a former criminal investigator and head of a handpicked interrogation team, gives us the first inside look at the U.S. military's attempt at more civilized interrogation techniques -- and their astounding success. The intelligence coup that enabled the June 7, 2006, air strike onZarqawi's rural safe house was the result of several keenly strategized interrogations, none of which involved torture or even "control" tactics.

Matthew and his team decided instead to get to know their opponents. Who were these monsters? Who were they working for? What were they trying to protect? Every day the "'gators" matched wits with a rogues' gallery of suspects brought in by Special Forces ("door kickers"): egomaniacs, bloodthirsty adolescents, opportunistic stereo repairmen, Sunni clerics horrified by the sectarian bloodbath, Al Qaeda fanatics, and good people in the wrong place at the wrong time. With most prisoners, negotiation was possible and psychological manipulation stunningly effective. But Matthew's commitment to cracking the case with these methods sometimes isolated his superiors and put his own career at risk.

This account is an unputdownable thriller -- more of a psychological suspense story than a war memoir. And indeed, the story reaches far past the current conflict in Iraq with a reminder that we don't have to become our enemy to defeat him. Matthew Alexander and his ilk, subtle enough and flexible enough to adapt to the challenges of modern, asymmetrical warfare, have proved to be our best weapons against terrorists all over the world.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access How to Break a Terrorist by Matthew Alexander,John Bruning in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Intelligence & Espionage. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

PROLOGUE

By God, your dreams will be defeated by our blood and by our bodies. What is coming is even worse.

—ABU MUSAB AL ZARQAWI

THE GOLDEN DOME

MARCH, 2006

THERE’S A JOKE interrogators like to tell: “What’s the difference between a ’gator and a used car salesman?” Answer: “A ’gator has to abide by the Geneva Conventions.”

We ’gators don’t hawk Chevys; we sell hope to prisoners and find targets for shooters. Today, my group of ’gators arrives in Iraq at a time when our country is searching for a better way to conduct sales.

After 9/11, military interrogators focused on two techniques: fear and control. The Army trained their ’gators to confront and dominate prisoners. This led down the disastrous path to the Abu Ghraib scandal. At Guantánamo Bay, the early interrogators not only abused the detainees, they tried to belittle their religious beliefs. I’d heard stories from a friend who had been there that some of the ’gators even tried to convert prisoners to Christianity.

These approaches rarely yielded results. When the media got wind of what those ’gators were doing, our disgrace was detailed on every news broadcast and front page from New York to Islamabad.

Things are about to change. Traveling inside the bowels of an air force C-130 transport, my group is among the first to bring a new approach to interrogating detainees. Respect, rapport, hope, cunning, and deception are our tools. The old ones—fear and control—are as obsolete as the buggy whip. Unfortunately, not everyone embraces change.

The C-130 sweeps low over mile after mile of nothingness. Sand dunes, flats, red-orange to the horizon are all I can see through my porthole window in the rear of our four-engine ride. It is as desolate as it was in biblical times. Two millenia later, little has changed but the methods with which we kill.

“Never thought I’d be back here again,” I remark to my seatmate, Ann. She’s a noncommissioned officer (NCO) in her early thirties, a tough competitor and an athlete on the air force volleyball team.

She passes me a handful of M&M’s. We’ve been swapping snacks all through the flight. “When were you here?” she asks, peering out at the desertscape below. Her long blonde hair peeks out from under her Kevlar helmet.

“Three years ago. April of o-three,” I reply.

That was a wild ride. I’d been stationed in Saudi Arabia as a counterintelligence agent. A one-day assignment had sent me north to Baghdad, shivering in the back of another C-130 Hercules.

Below us today the southern Iraqi desert looks calm. Nothing moves; the small towns we pass over appear empty. In 2003 it was a different story. We flew in at night, and I watched the remnants of the war go by from 200 feet, a set of night-vision goggles strapped to my head. Tracer bullets and triple A (antiaircraft artillery) arced out of the dark ground past our aircraft, our pilot banking the Herc hard to avoid the barrages. Most of the way north, the night was laced with fire. Yet when we landed at Baghdad International, we found the place eerie and quiet. Burned-out tanks and armored vehicles lay broken around the perimeter. I later found out they’d been destroyed by marauding A-10 Warthogs.

On this return flight, we face no opposition. The pilots fly low and smooth. The cargo section of these C-130’s is always cold. I pop the M&M’s into my mouth and fold my arms across my chest. The engines beat a steady cadence as the C-130 shivers and bucks. Ann puts her iPod’s buds in her ears and closes her eyes. Next to her, I start to doze.

An hour later, I wake up. A quick check out of the porthole reveals the sprawl of Baghdad below. We cross the Tigris River, and I see one of Saddam’s former palaces that I’d seen in ’03.

“We’re getting close,” I say to Ann.

She removes her earbuds.

“What?” she asks.

Mike, another agent in my group, leans in from across the aisle to join our conversation. He offers me beef jerky, and I take a piece.

“We’re getting close,” I repeat myself.

We reach our destination, a base north of Baghdad. The C-130 swings into the pattern and within minutes, the pilots paint the big transport onto the runway. We taxi for a little while, then swing into a parking space. The pilots cut the engines. The ramp behind us drops, and I see several enlisted men step inside the bird to grab our bags. Each of us brought five duffels plus our gun cases. When we walk, we look like two-legged baggage carts.

“Welcome to the war,” somebody says behind me.

After hours of those big turboprops churning away, all is quiet. We descend from the side door just aft of the cockpit. As we hit the tarmac, a bus drives up. A female civilian contractor jumps out and says, “Okay, load up!”

Just as I find a seat on the bus I hear a dull thump, like somebody’s just slammed a door in a nearby building—except there aren’t any nearby buildings.

A siren starts to wail.

“Oh my God!” screams our driver. “Mortars!”

She stands up from behind the wheel and dives for the nearly closed door, where she promptly gets stuck. Half-in, half-out of the bus she screams, “Mortars! Mortars!”

We look on with wry smiles.

Another dull thud echoes in the distance. The driver flies into a panic. “Get to the bunkers now! Bunkers! Move!” She finally extricates herself from the door and I see her running at high speed down the tarmac.

“Shall we?” I ask Ann.

“Better than waiting for her to come back.”

We get off the bus and lope after our driver. We watch her head into a long concrete shelter and we follow and duck inside behind her. It is pitch black.

Another thump. This one seems closer. The ground shakes a little.

It is very dark in here. The bunker is more like a long, U-shaped tunnel. I can’t help but think about bugs and spiders. This would be their Graceland.

“Watch out for camel spiders,” I say to Ann. She’s still next to me.

“What’s a camel spider?” she asks.

“A big, aggressive desert spider,” says a nearby voice. I can’t see who said that, but I recognize the voice. It is Mike, our Cajun. Back home he’s a lawyer and a former police sniper. He’s a fit thirty-year-old civilian agent obsessed with tactical gear.

“How big?” Ann asks dubiously. She’s not sure if we’re pulling her leg. We’re not.

“About as big as your hand,” I say.

“I hear they can jump three feet high,” says Steve. He’s a thirty-year-old NCO and another agent in our group of air force investigators-turned-interrogators. This tall, buzz-cut adrenaline junkie from the Midwest likes racing funny cars in his spare time. In the States, his cockiness was suspect. Out here, I wonder if it won’t be exactly what we need.

“Seriously?” Ann asks.

Thump! The bunker shivers. Another mortar has landed. This one even closer.

“I’m still more worried about the spiders,” Mike says.

I have visions of a camel spider scuttling across my boot. I look down, but it’s so dark that I can’t even see my feet.

The all-clear signal sounds. We file out of the bunker and make our way back to the bus. The driver tails us, looking haggard and embarrassed. Her panic attack cost her whatever respect we could have for her. We climb aboard her bus and she takes us to our next stop.

We “inprocess,” waiting in line for the admin types to stamp our paperwork. We have no idea what’s taking them so long. Hurry up. Wait. Hurry up. Wait. It’s the rhythm of the military.

Steve finishes first and walks over to us. “Hey, one of the admin guys just told me a mortar round landed right around the corner and killed a soldier.”

The news is like cold water. Any thought of complaining about the wait dies on our tongues. We’d been cavalier about the attack. Now it seems real.

A half hour passes before we are processed. Our driver shows up with the first sergeant and shuttles us across the base to the Special Forces compound where we’ll stay until we accomplish our mission (whatever that is).

When I went home in June, 2003, I thought the war was over—mission accomplished—but it had just changed form. We’ve arrived in Iraq near the war’s third anniversary. The army, severely stretched between two wars and short of personnel, has reached out to the other services for help. Our small group was handpicked by the air force to go to Iraq as interrogators to assist our brothers in green. We volunteered not knowing what we’d be doing or where. Some of us thought we’d go to Afghanistan, perhaps joining the hunt for Osama bin Laden. Only at the last minute before we left the States did we find out where we were going. We still don’t know our mission, but we’ve been told it has the highest priority.

We’re all special agents and experienced criminal investigators for the air force. One of us is a civilian agent and the rest of us are military. I’m the only officer. Ever since the Abu Ghraib fiasco, the army has struggled in searching for new ways to extract information from detainees. We offer an alternative approach. In the weeks to come, we’ll try to prove our new techniques work, but if we cross the wrong people, we’ll be sent home. They told us that much before we left for the sandbox.

Later that night, after stashing our bags in our trailer homes, we sit in the interrogation unit’s briefing room down the hall from the commander’s office.

My agents are called one by one into the commander’s office for an evaluation. All of them pass. Finally, a tall, blackhaired Asian-American man with a bushy black beard steps into the briefing room. “Matthew?” he says to me.

I step forward. He regards me and says, “I’m David, the senior interrogator.” He leads me to the commander’s office and follows me inside.

“Have a seat,” David says.

I look around. There’s only one free chair, a plush, overstuffed leather number next to one of the desks, so I settle into it.

The office is cramped, made even more claustrophobic by two large desks squatting in opposite corners. Behind one is a gruff-looking sergeant major. David sits next to the door. A third man watches me intently from the far corner, and the interrogation unit commander, Roger, sits behind a desk to my right.

Everyone else sitting in the room is in ergonomic hell. I feel uneasy as I take the best seat in the house. Roger explains to me that this is an informal board desig...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Author’s Note

- Contents

- Foreword

- PART I PROLOGUE

- PART II COMING INTO FOCUS

- PART III GOING IN CIRCLES

- PART IV DICE ROLL

- Epilogue: Killing the Hydra