- 336 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

“Memoir writers, buy this book, put it on your personal altar, or carry it with you as you traverse the deep ruts of your old road.” —Tom Spanbauer, author of The Man Who Fell in Love with the Moon

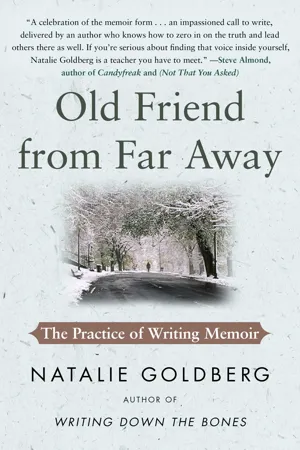

Old Friend from Far Away teaches writers how to tap into their unique memories to tell their story.

Twenty years ago Natalie Goldberg’s classic, Writing Down the Bones, broke new ground in its approach to writing as a practice. Now, Old Friend from Far Away—her first book since Writing Down the Bones to focus solely on writing—reaffirms Goldberg’s status as a foremost teacher of writing, and completely transforms the practice of writing memoir.

To write memoir, we must first know how to remember. Through timed, associative, and meditative exercises, Old Friend from Far Away guides you to the attentive state of thought in which you discover and open forgotten doors of memory. At once a beautifully written celebration of the memoir form, an innovative course full of practical teachings, and a deeply affecting meditation on consciousness, love, life, and death, Old Friend from Far Away welcomes aspiring writers of all levels and encourages them to find their unique voice to tell their stories. Like Writing Down the Bones, it will become an old friend to which readers return again and again.

Old Friend from Far Away teaches writers how to tap into their unique memories to tell their story.

Twenty years ago Natalie Goldberg’s classic, Writing Down the Bones, broke new ground in its approach to writing as a practice. Now, Old Friend from Far Away—her first book since Writing Down the Bones to focus solely on writing—reaffirms Goldberg’s status as a foremost teacher of writing, and completely transforms the practice of writing memoir.

To write memoir, we must first know how to remember. Through timed, associative, and meditative exercises, Old Friend from Far Away guides you to the attentive state of thought in which you discover and open forgotten doors of memory. At once a beautifully written celebration of the memoir form, an innovative course full of practical teachings, and a deeply affecting meditation on consciousness, love, life, and death, Old Friend from Far Away welcomes aspiring writers of all levels and encourages them to find their unique voice to tell their stories. Like Writing Down the Bones, it will become an old friend to which readers return again and again.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Old Friend from Far Away by Natalie Goldberg in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Social Science Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Test III

I Remember

Two minutes on each of these topics:

____A memory of cabbage

____Some instance of a war

____A cup you loved

____A peace march you didn’t attend

Monkey Mind

Where do thoughts come from, memories, words? All of it is carried in mind. Note: I didn’t say “your mind” but “mind” itself because we are all run by the same principles of mind. We each have our individual details but the functioning of mind works the same way in all people.

You interrupt here to assure me that you are way more messed up than most minds. You won’t fit, you can’t write, you are hopeless.

Everyone feels this way. Shut up and listen. Yes, you are special but your mind isn’t. Your mind at its base functions like all other human minds, just as your legs walk similarly to other people’s and your hands do the same gripping and touching, poking and holding.

One basic thing the mind does is generate thoughts. The problem is: it’s hard to settle it down. The mind has a tendency to wander and drift off or barrage us. Even before we get to a first thought—the ones that carry vitality, that are connected to the body—we are lost in critical second and third thoughts: “I can’t do this writing. There’s a sale on tuna. My kids need attention. I have nothing to say. I’m boring.” These divisive, churning thoughts are telling you a lot, but not what they are actually saying. It’s an indication of nervousness and energy. It tells you you want writing bad, but at the same time are terrified to write.

We call this monkey mind or the critic or editor. We run from this voice, but at the same time we believe it, listen to it as though it were God declaring the sacred truth: yes, indeed, you are a dud. And don’t try to be anybody. Don’t speak.

Everyone has this voice. Even if you had the ultimate in supportive parents and encouraging teachers, the human mind generates this old survival technique. Can you imagine if cave people had decided to wander off and contemplate their past? They wouldn’t have gotten meat on the table. But this inheritance is not obsolete. We still have a fear of our inner world. Will we survive if we take time to think, to examine, to understand? Instead we prefer to go hurtling from one war to another, from one marriage to another, from one painful situation smack-dab into one more. We think that if we stay blind, ignorant, and keep going, we will make it through.

And plop!—in the middle of all this you decide you want to write a memoir, to look back, to ponder. Of course, your deep survival mechanism, old monkey mind, is going to go bananas.

It wants to protect you at all costs. But it’s also testing you. Do you have the mettle, the wherewithal, to behold the gems of your heart? The jewels are sometimes handed to you bleeding, encased in betrayal and deception, reeking of disappointment and disillusion, slimy with heartbreak and pain. How bad do you want the bright pearls?

This is important for you to understand. It helps you to bear up under the screeching in your ear. Monkey mind can take the form of your mother, a nun, a professor, a priest—whatever it needs in order to do the job.

Your job, in the middle of this noise, is to keep your hand moving, to be steadfast. Find people to do timed writings with you, make a schedule even if it’s only twice a week for half an hour—and stay with that schedule. (Be realistic. If you can only write once in the coming week, put it on your calendar. And show up. You don’t blithely cancel a doctor’s appointment—this date is as important.) Do what it takes.

With time and determination—sometimes a lot of determination—monkey mind does quiet down, does settle. It never goes away, but you create a genuine understanding of it. It will never so easily run your life again. At the same time, you are developing a curiosity, a commitment, and a love of the writing process. You are following what pleases you. Monkey mind’s screeching can’t get as much attention.

Eventually monkey mind’s concern with survival transforms. You finally hold the jewels. You rule now. Monkey mind becomes the guardian at your gate. She’s not a squawker anymore. She pays silent vigil, has joined your forces. But you won’t recognize her right away. Your armor now is compassion, your defense, love. The jewels are in your hands. No one else’s.

Wild at Heart

In the essay “Wild at Heart” in a book called The Poem That Changed America: “Howl” Fifty Years Later, Vivian Gornick writes:

Allen Ginsberg was born in Newark, New Jersey, in 1926 to Louis and Naomi Ginsberg; the father was a published poet, a high school teacher, and a socialist; the mother, an enchanting free spirit, a passionate communist, and a woman who lost her mental stability in her thirties (ultimately she was placed in an institution and lobotomized). Allen and his brother grew up inside a chaotic mixture of striving respectability, left-wing bohemianism, and certifiable madness in the living room. It all felt large to the complicated, oversensitive boy who, discovering that he lusted after boys, began to feel mad himself and, like his paranoid parents, threatened by, yet defiant of, the America beyond the front door.

None of this accounts for Allen Ginsberg; it only describes the raw material that, when the time was right, would convert into a poetic vision of mythic proportion that merged brilliantly with its moment: the complicated aftermath of the Second World War…

Let’s look at this. The first paragraph is a detailed list of the specifics of Allen Ginsberg’s early life. Yes, he was born in Newark; yes, yes, his father was what Gornick says he was and his mother is described aptly. It is true he was inclined to love boys when he was young. But then the stunning line: “None of this accounts for Allen Ginsberg.” Huh? I thought in writing we build up the details and create a picture of who we are? This is exactly the problematic trick.

You can be told what materials make a hand—the skin, the fine bones, the nails, the persnickety thumb, but then all the ingredients fuse and explode. Whose hand is this? A leap happens. Allen Ginsberg became a huge figure that changed the face of poetry. Notice, too, it is not only Allen Ginsberg the man, who created himself, but also his work that met the moment—he ignited with his time. Something dynamic happened.

We don’t live in a vacuum. That extra ingredient—the flint snapping across the rough edge of our era, the day the news broke, the flavor of our decade, our generation—makes the spark spring up. You never talk just for yourself. A whole flame shoots through you. Even if you’re not aware of it, even though your sorrow, your pain is individual, it is also connected to the large river of suffering. When you join the two, something materializes.

When Bob Dylan sat in the third row first seat in B. J. Rolfzen’s English class in Hibbing High School, this public school teacher had no idea that this quiet boy would, two years after he left his family at eighteen, write some of the best songs of the twentieth century.

Allen Ginsberg and Bob Dylan were brought up thousands of miles apart. Bob Dylan had stable middle-class parents. His father sold electrical equipment, stoves, refrigerators to iron ore miners in Northern Minnesota. His mother belonged to B’nai B’rith. But “none of this accounts for” Bob Dylan. Dylan took a leap into another life. As an adult fourteen years older than Bob Dylan, Allen Ginsberg heard Dylan’s songs and knew the torch of inspiration, of freedom, had been passed on to the next generation.

We each are endowed with original mind, which is like a river under the visible river, unconditioned, the immediate point where our clear consciousness meets the vast unknown; yet we’ve blown smoke screens to cloud it. Fake images, false illusions. When Allen Ginsberg sat down one night in his twenties to write what was really on his mind, he replaced the rhymed poesy he’d learned from his father and from school. That decision was the beginning of one of the most famous poems in our language. Imagine! the power of writing what’s truly on your mind. What you really see, think, and feel. Rather than what you are told you should think, see, and feel. It causes a revolution—or at the very least, a damn fine poem.

Raw material is poured into a burning vat and something different comes out. Maybe in past generations when people didn’t leave home and raised their children near their parents in the same town where they grew up and if your father was a steelworker, you became a steelworker or if your mother was a secretary, you became an office manager, you might not have had the luxury of wondering about yourself. You might not ponder how A became B and produced C. It might all have been obvious. But I bet that even a third-generation physician on his way to work in his hometown who suddenly notices the glint off a parking meter, stops still and questions: Who am I? and is left in this swirl that doesn’t make sense. One lives and then one dies? Who thought this scheme up anyway?

We go back to our past to piece things together. “I always loved coffee ice cream, roast beef, and hopscotch.” It still makes us happy to remember these things, but how did they lead to moving from the sprawl of a city on the East Coast to listening to mourning doves on a dead branch outside our kitchen door in the vast West? Can we turn around fast enough to catch a glimpse of our own face?

In some ways writing is our attempt to grasp what went on. We want an answer. We want things to be black and white, to be obvious and ordered. Oh, the relief. But have you noticed, it doesn’t work that way? We live more in the mix of black and white, in the gray—or in the brilliant colors of the undefined moment.

Can we bear to hang out in incongruity, in that big word, paradox? How did I end up with the partner I have, the children that sprang from me? How can I love my father, who betrayed me? This isn’t a call to ditch it all even though nothing makes sense. Instead, don’t reject anything—the person who did something unforgivable, the white rose at the edge of your driveway, the split pea soup you never liked.

There are no great answers for who we are. Don’t wait for them. Pick up the pen and right now in ten furious minutes tell the story of your life. I’m not kidding. Ten minutes of continuous writing is much more expedient than ten years of musing and getting nowhere.

Include the false starts, the wrong turns, the one surprising right thing that happened. A lot of it is ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Praise

- Colophon

- ALSO BY NATALIE GOLDBERG

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Read this Introduction

- Note to Reader

- Go

- I Remember

- Test I

- Test II

- Test III—I Remember

- Test IV

- Test V

- Test VI

- Test VII

- Test VIII

- Test IX

- About the Author