eBook - ePub

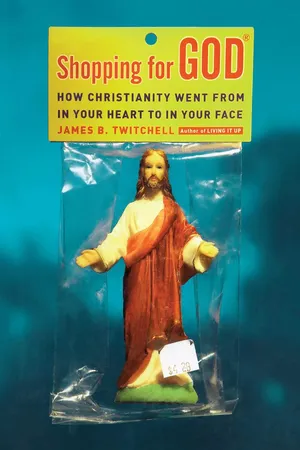

Shopping for God

How Christianity Went from In Your Heart to In Your Face

- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Not so long ago religion was a personal matter that was seldom discussed in public. No longer. Today religion is everywhere, from books to movies to television to the internet-to say nothing about politics. Now religion is marketed and advertised like any other product or service. How did this happen? And what does it mean for religion and for our culture?

Just as we shop for goods and services, we shop for church. A couple of generations ago Americans remained in the faith they were born into. Today, many Americans change their denomination or religion, sometimes several times. Churches that know how to appeal to those shopping for God are thriving. Think megachurches. Churches that don't know how to do this or don't bother are fading away. Think mainline Protestant churches.

Religion is now celebrated and shown off like a fashion accessory. We can wear our religious affiliation like a designer logo. But, says James Twitchell, this isn't because Americans are undergoing another Great Awakening; rather, it's a sign that religion providers-that is, churches-have learned how to market themselves. There is more competition among churches than ever in our history. Filling the pew is an exercise in salesmanship, and as with any marketing campaign, it requires establishing a brand identity. Successful pastors ("pastorpreneurs," Twitchell calls them) know how to speak the language of Madison Avenue as well as the language of the Bible.

In this witty, engaging book, Twitchell describes his own experiences trying out different churches to discover who knows how to "do church" well. He takes readers into the land of karaoke Christianity, where old-style contemplative sedate religion has been transformed into a public, interactive event with giant-screen televisions, generic iconography (when there is any at all), and ample parking.

Rarely has America's religious culture been examined so perceptively and so entertainingly. Shopping for God does for religion what Fast Food Nation has done for food.

Just as we shop for goods and services, we shop for church. A couple of generations ago Americans remained in the faith they were born into. Today, many Americans change their denomination or religion, sometimes several times. Churches that know how to appeal to those shopping for God are thriving. Think megachurches. Churches that don't know how to do this or don't bother are fading away. Think mainline Protestant churches.

Religion is now celebrated and shown off like a fashion accessory. We can wear our religious affiliation like a designer logo. But, says James Twitchell, this isn't because Americans are undergoing another Great Awakening; rather, it's a sign that religion providers-that is, churches-have learned how to market themselves. There is more competition among churches than ever in our history. Filling the pew is an exercise in salesmanship, and as with any marketing campaign, it requires establishing a brand identity. Successful pastors ("pastorpreneurs," Twitchell calls them) know how to speak the language of Madison Avenue as well as the language of the Bible.

In this witty, engaging book, Twitchell describes his own experiences trying out different churches to discover who knows how to "do church" well. He takes readers into the land of karaoke Christianity, where old-style contemplative sedate religion has been transformed into a public, interactive event with giant-screen televisions, generic iconography (when there is any at all), and ample parking.

Rarely has America's religious culture been examined so perceptively and so entertainingly. Shopping for God does for religion what Fast Food Nation has done for food.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Shopping for God by James B. Twitchell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Religion. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

Oh Lord, Why U.S.? An Overview of the Spiritual Marketplace

This is not a book about God. Turn back now if that’s what you’re after. Save your time, money, and perhaps your temper. This book is not about belief, or spirituality, or the yearning for transcendence. Don’t get me wrong: those are truly important matters. Rather, Shopping for God is about how some humans—modern-day Christians, to be exact—go about the process of consuming—of buying and selling, if you will—the religious experience. This book is about what happens when there is a free market in religious products, more commonly called beliefs. Essentially, how are the sensations of these beliefs generated, marketed, and consumed? Who pays? How much? And how come the markets are so roiled up right now in the United States? Or have they always been that way?

By extension, why are the markets so docile in Western Europe? In 1900 almost everyone in Europe was Christian. Now three out of four Europeans identify themselves as Christians. At the same time, the percentage who say they are nonreligious has soared from less than 1 percent of the population to 15 percent. According to the Center for the Study of Global Christianity, another 3 percent say they don’t believe in God at all. Churches in Europe are in free fall, plenty of sellers but no new buyers. According to the World Values Survey in 2000, in twelve major European countries, 38 percent of the population say they never or practically never attend church. France’s 60 percent nonattendance rate is the highest in that group. Here in the U.S., only 16 percent say they rarely go to church.

No wonder Europeans look at us and think we’re nuts. Are we? We’re consuming the stuff in bulk 24-7. Religion here is perpetually ripe. Are we—a nation disparaged as shallow materialists—more deeply concerned about the eternal verities than our high-minded European cousins? That is doubtful. So what gives?

One answer is that we’re doing a better job of selling religion. Or to put it in the lingo of Econ 101, we are doing a robust business in supplying valuable religious experiences for shoppers at reasonable prices. But, if so, how so? And do I really mean to suggest that the marketplace is not just a metaphor, but a reality? Does the small church on the corner operate like the gas station? What about the megachurch out there by the interstate—is it like a big-box store? How come the church downtown with exactly the same product is in shambles? And, while we’re on this vulgar subject, how do churches sell? How do they compete for customers, called believers and parishioners in some venues and seekers in others, if indeed they do? They say they don’t compete. At least they say this in public.

Are the religion dealers, if I may call them that, in any way like the car dealers on the edge of town? And what of the denominations that they represent—do they compete? How similar is their behavior to what happens when General Motors goes up against Ford or Chrysler? And what happens when foreign lower-cost suppliers (like Honda) and higher-end suppliers (like Mercedes-Benz) enter the market? And how about home-grown low-cost discounters (like Costco) or web-based services (like Autobytel.com) that often sell cars almost entirely on price? The analogy is blasphemous, yes, but it may help us understand not just the spiritual marketplace but the current state of American culture.

If denominations don’t compete for consumers (and they say they are interested only in new believers or lapsed believers, not in brand switchers, or what they call transfer growth), why are almost all of them spending millions of parishioners’ dollars on advertising campaigns? Why are they hiring so many marketing consultants? We will look at some of these denominational campaigns because it’s clear that they are poaching other flocks. There is an entire new business model called the Church Growth Movement to help them along.

Essentially, this book is about how religious sensation is currently being manufactured, branded, packaged, shipped out, and consumed. The competition is fierce. Some old-line suppliers (think Episcopal, Methodist, Lutheran) are losing market share at an alarming rate. Some of them are barely able to fund their pensions without dipping into investment capital. For them, things are going to get worse, a lot worse. They can’t change their product fast enough. For them, doing church is a two-hour Sunday affair, but for an increasing number of super-efficient big-box churches, it can last for days, even the whole week.

These new churches, megachurches, are run by a very market-savvy class of speculators whom I will call pastorpreneurs. By clever use of marketing techniques, they have been able to create what are essentially city-states of believers. They are the low-cost discounters of rapture that promise to shift the entire industry away from top-down denominationalism toward stand-alone communities. Small case in point: in the last few years, we all have learned a new common language. We use born-again, inerrancy, rapture, left behind, megachurch, and evangelical in ways that our parents never did. Some of us even use the word crusade.

Religion Goes Pop

Religion has become a major source of pop culture. You can see this in the role of celebrity. The old-style celeb kept his religion to himself. Now he’s in your face. In a way, however, this represents a return to the original definition of celebrity, namely, the one who celebrates the religious event. Nothing is more revered in American popcult than the renown of being well-known.

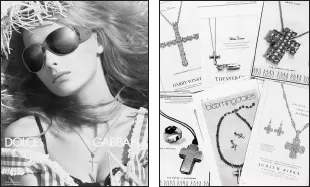

Religion as fashion statement or fashion statement as religion?

So we all know of Mel Gibson’s evangelical Catholicism and Tom Cruise’s Scientology. And what of Madonna and kabbalah, Richard Gere and Buddhism, Muhammad Ali and Islam? I think it’s safe to say that a generation ago, most entertainers did not wear their religiosity on their sleeves, or anywhere else for that matter. Madison Avenue and the film studios saw to that. Now, just the reverse. You wear your belief on your sleeves, right next to your religious bling.

Since the religious experience is moved through media, through delivery systems (of which the church itself is becoming less important), let’s have a quick look at the transformations being wrought in film, television, radio, the internet, and even dusty old book publishing. What we’ll see is how transformative the new version of Christianity has become on the very vehicles that move it around.

MOVIES

If, as the saying goes, the religion of Hollywood is money, then the returns of Christiantainment have proven a God-send. Back in the 1950s, as television was stealing the movies’ thunder, there was a spate of big-budget, big-screen, big-star, little-religion movies called “Sword & Sandal” epics. Some are still cycling through late night television: The Robe, The Ten Commandments, and Ben-Hur. The Bible was invoked more for Sturm und Drang, son et lumière, and, let’s face it, really steamy love scenes than for any presentation of dogma.

It was in the marketing of one of these movies, incidentally, that the faux Ten Commandments tablet first appeared in a public space. In many ways its exploitation neatly condenses the theme of this book. As Cecil B. DeMille readied his costly Paramount production of The Ten Commandments for release, he happened on an ingenious publicity scheme. In partnership with the Fraternal Order of Eagles, a nationwide association of civic-minded clubs founded by theater owners, he sponsored the construction of several thousand Ten Commandments monuments throughout the country. DeMille, a Jew, was interested in plugging the film, not Christianity.

A generation later, two of these DeMille-inspired granite monuments, first in Alabama and then on the grounds of the Texas capital in Austin, became the focus of the Ten Commandments case before the U.S. Supreme Court. What was essentially an advertisement for an entertainment had become a deadly serious pronouncement of in-your-face faith.

The modern biblical epic is nothing if not drenched in the blood of Calvary. Adios, Samson and Delilah, David and Bathsheba, Demetrius, and all those gladiatorial interludes with the smarmy and wonderfully named Victor Mature. Golgotha, usually glimpsed only as the curtain falls in the Sword & Sandal epic, is now stage center. The modern version, viz. Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ, is nothing if not a total rearrangement of the genre. This film revels in small budget, no star, no love scenes. Shhh, please, this is a serious re-creation of what really happened.

Nothing in film history compares with Gibson’s film. It is truly sui generis. And as such, it’s a condensation of broader changes. First, it is unflaggingly serious. The language is Aramaic, for goodness’ sake. If not literally true, then why use the real language? Next, it was released in a totally un-Hollywood way. The movie was initially shown in a venue aptly suited and wired for this experience: the megachurch. After all, when your projection and sound equipment rivals that of the local cineplex, why not use it to showcase film? And since the megachurch is open 24-7, you can schedule multiple viewings. And there are stadium seats and amphitheater architecture. This place was ordained for film.

The marketing of The Passion was still more revelatory of cultural shifts. The initial advertising did not go from studio-to-you, but from studio-to-minister-to-you. If you ever wanted to see the much-ballyhooed targeted entertainment, here it is. And finally, The Passion was what the earlier attempts only dreamed of: it became a legitimate blockbuster. Not only did it gross some $400 million in the U.S., not only did it revolutionize how movies are taken to market, but it also had what is called a huge back end.

The big money in movies is not just in theatrical display but in this aftermarket. Here is the new way that many movies will be seen, not out of the house and in the theater, but out of the house and in the church. Like King Gillette and the disposable razor, with some products you can give the thing away (the razor, the movie) and make up for it in the aftermarket (the blades, the accessories). The big money is not at the box office gross but in the, say, ten million DVDs that come after the show. People want to own this “text,” to add it to their video library. In earlier days, a family had a going-to-church Bible and a stay-at-home family Bible. The family Bible now sits next to The Passion DVD.

So too the merchandise that travels with the experience, as the crucifixion nails (licensed by Mr. Gibson) worn around the neck to announce that you’ve not just seen the movie, you’ve suffered the experience. You can buy this memorial merchandise at the store inside your megachurch.

How powerful was The Passion as a marketing event? An online poll on Beliefnet.com, answered by about twelve thousand people, found that 62 percent were reading the Bible more often after seeing the film. The poll also found that 41 percent had a more positive view of the Bible after the movie. But that’s not the count that really counted. Show me the money. In Hollywood there is a new term to describe the receipts from such events; they are now being called Passion dollars.

In the parting of the revenue seas are coming the never-ending Left Behind series of novels based on apocalyptic themes, as well as The Chronicles of Narnia, The Gospel, and countless other Christian stories. When the movie version of The End Is Near opened in 2005, it put in a cameo at the Bijou, then went straight to video and then straight to the family library. Left Behind: World at War, for instance, was the first film ever to open only in churches, not theaters. The movie premiered, on a late-October weekend, on 3,200 screens, largely in churches. You could buy the DVD and other mementos at the display table on your way out.

The struggle to find Passion dollars has become so wonderfully crazed that 20th Century Fox, a minor subsidiary of News Corp., has announced an upcoming movie based on John Milton’s epic poem Paradise Lost. Its producer, Vincent Newman, has pledged to keep the script faithful to the original 1667 text. Not that the story of Satan’s rebellion and expulsion from heaven and his subsequent role in the fall of man is not a rollicking good tale, but if the 1667 text is followed, it will indeed show how devout faith can be. English professors at least are on pins and needles.

What does this marketing portend? Instead of renting or buying all the seats in a theater, as did many churches with Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ, congregations themselves will debut the film in their sanctuary after paying a nominal licensing fee. The revolutionary film-release strategy seems like a no-brainer. Here’s why: There are more than two hundred thousand churches in America compared to five thousand theaters, and many of these churches already have state-of-the-art projection equipment. But the real marketing genius is to realize that the audience does not regard this as mere entertainment but as something to own and treasure on DVD. See the film. Now buy a c...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Colophon

- ALSO BY JAMES B. TWITCHELL

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Chapter One Oh Lord, Why U.S.? An Overview of the Spiritual Marketplace

- Chapter Two Another Great Awakening?

- Chapter Three Let’s Go Shopping: Brought to You by God®

- Chapter Four Hatch, Match, Dispatch, or Baptized, Married, Buried: The Work of Denominations

- Chapter Five Holy Franchise: Marketing Religion in a Scramble Economy

- Chapter Six The United Methodist Example

- Chapter Seven The Church Impotent: What’s Wrong with the Mainlines?

- Chapter Eight Out of the Ivory Tower and into the Missionary Fields

- Chapter Nine The Megachurch: “If You Are Calling about a Death in the Family, Press 8.”

- Chapter Ten And This Too Shall Pass: The Future of Megas

- Endnotes

- Index