- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

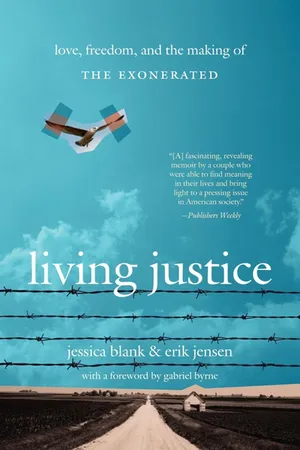

A love story. An artistic journey. A matter of life and death...

In 2000, Jessica Blank and Erik Jensen embarked on a tour across America -- one that would give them a glimpse of the darker side of the justice system and, at the same time, reveal to them just how resilient the human spirit can be. They were a pair of young actors from New York who wanted to learn more about our country's exonerated -- men and women who had been sentenced to die for crimes they didn't commit, who spent anywhere from two to twenty-two years on death row, and who were freed amidst overwhelming evidence of their innocence. The result of their journey was The Exonerated, New York Times number one play of 2002, which was embraced by such acting luminaries as Ossie Davis, Richard Dreyfuss, Danny Glover, Tim Robbins, Susan Sarandon, and Robin Williams.

Living Justice is Jessica and Erik's fascinating, behind-the-scenes account of the creation of their play. A tale of artistic expression and political awakening, innocence lost and wisdom won, this is above all a story about two people who fall in love while pursuing their passion and learn -- through the stories of the exonerated -- what freedom truly means.

In 2000, Jessica Blank and Erik Jensen embarked on a tour across America -- one that would give them a glimpse of the darker side of the justice system and, at the same time, reveal to them just how resilient the human spirit can be. They were a pair of young actors from New York who wanted to learn more about our country's exonerated -- men and women who had been sentenced to die for crimes they didn't commit, who spent anywhere from two to twenty-two years on death row, and who were freed amidst overwhelming evidence of their innocence. The result of their journey was The Exonerated, New York Times number one play of 2002, which was embraced by such acting luminaries as Ossie Davis, Richard Dreyfuss, Danny Glover, Tim Robbins, Susan Sarandon, and Robin Williams.

Living Justice is Jessica and Erik's fascinating, behind-the-scenes account of the creation of their play. A tale of artistic expression and political awakening, innocence lost and wisdom won, this is above all a story about two people who fall in love while pursuing their passion and learn -- through the stories of the exonerated -- what freedom truly means.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Living Justice by Jessica Blank,Erik Jensen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Civil Rights in Law. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

The two of us had been dating just over a month. Erik had lived in New York City for almost a decade, making a steady living as an actor in independent films and TV. Jessica’d just shown up in the city nine months earlier, after graduating from college in Minnesota. She was training at an acting studio, making the rounds, spending her days doing political organizing and her evenings doing spoken-word poetry. Both of us had your typical broke bohemian artsy New York lifestyle.

When we’d first met, Erik was deep in the throes of self-imposed bachelorhood. He’d bribed someone to obtain the lease on his East Village apartment, then turned his little rent-stabilized hardwood hovel into a fortress, usually spending his evenings in front of one of Manhattan’s few working fireplaces accompanied by a stack of comic books, a script, and his Brittany spaniel Zooey. Erik had a steady, skinny little New York life complete with hundreds of paperbacks, acting work that he got paid for but would happily have done for free, and a dog that didn’t smell too bad. He could smoke a pack and a half of cigarettes a day, eat as many Sno Balls as Hostess could ship into Manhattan, and throw laundry on his fire escape without having to answer to anyone (except when the super complained about the tube socks hanging off the downstairs neighbor’s window garden).

Jessica, on the other hand, was caught up in a whirlwind of just-moved-to-New-York. She had her starter New York City apartment—which, like many starter New York apartments, was in New Jersey—which she used exclusively to crash out at 4 a.m. after running around the city all day and night. Every day was totally different; not yet jaded, she made new friends every five minutes and was dating, um, a bunch of different people. She knew what she loved (politics, acting, writing) but was still stumbling around trying to figure out how on earth to do all three things and make a living. Happy to be finished with college, not entirely sure what to do next, she let the city lead the way and wound up organizing politically minded artists, studying acting, making the audition rounds, and hanging out at poetry slams.

We’d met through the tangled and tiny social web of young New York actors when Erik crashed his friend Kelly’s date with Jessica. Erik had just started a run of a new play, and it had been a tough audience that night. Erik stopped off at Kelly’s East Village restaurant on his way home, hoping for some company and consolation. And a free beer.

Kelly was indeed there, sitting with Jessica at a table in the back. Erik said hi to Kelly, spilled a beer on himself, and introduced himself to Jessica. Then he sat down and started describing that night’s performance. Kelly knew the drill: When in doubt, blame it on the audience. Then the weather. Then the stage manager.

It wasn’t till Jessica got up to go to the bathroom that Kelly had a chance to lean over to Erik and tell him to quit talking about himself so much. “I’m trying to spend some time with this girl, man. You need to step off.” From the subtle pressure Kelly was applying to Erik’s knuckles, Erik knew he meant it.

When Jessica returned from the bathroom, she found Erik strangely silent. Soon after that, Erik went home to walk the dog, but he managed to slip Jessica his phone number first, ostensibly so he could get her free tickets to his play.

Time passed; Jessica and Kelly didn’t work out; she called Erik to take him up on the free-tickets offer. Unbeknownst to her, Erik had used up all his comps by then, but he told her it was no problem to set up free tickets; she should come down to the theater that Friday, maybe they could go have a drink with the playwright after. Then Erik went out and hawked some used books to pay for it. So much for self-imposed bachelorhood.

Jessica showed up as promised, picked up her $65 “free” ticket, watched the play, and went out after with Erik, the playwright Arthur Kopit, and his wife, writer Leslie Garis. We got drunk, ate pie, and talked about theater and writing. Going from one café to another, we lingered behind Arthur and Leslie, talking to each other a mile a minute, overlapping, interrupting each other a lot.

Leslie told us later she’d eavesdropped on us as she and Arthur walked ahead, and that she went home that night so struck by the conversation that she wrote it down. We’re still trying to get our hands on that transcript—we have a feeling it might be embarrassing.

We spent the next month and a half or so starting to really like each other, being afraid of starting to really like each other, cataloging each other’s strengths and weaknesses, trying to figure out how compatible we were, boring our friends.

One of the areas in which we were still feeling each other out was politics. We were both decidedly left of center—and maybe that was enough common ground—but we came from very different political backgrounds, and our approaches were, well, different. Erik had grown up in rural and suburban Minnesota, the grandson of a highway patrolman, the great-grandson of a judge. Minnesota is a progressive state with a strong populist streak, infused with the belief that if we elect honest, hardworking, good-hearted leaders, and work hard ourselves, things will turn out pretty much okay. Despite having run off to an East Coast acting school and the proverbial “big city” (his father actually used that phrase once) after graduation, when it came to politics, Erik was a child of Minnesota, a registered Democrat who balanced his populist bent with a lot of faith in the system.

Jessica, on the other hand, was the daughter of sixties lefties. Her parents had been early protesters of the Vietnam War, attended MLK’s March on Washington, and helped found Vietnam Veterans Against the War. Jessica’s mom is a movement educator with a background in modern dance and a devotion to progressive schooling; her dad is a jazz-piano-playing psychoanalyst. They moved to Washington, D.C., in the early eighties so Jessica’s mom could expand her practice, and so Jessica’s dad could put their family’s ideals to work at the Veterans Administration, fighting to preserve benefits for Vietnam vets who’d more or less been discarded by their government, educating the public about the traumas caused by war. Jessica grew up amidst noisy political dinner-table conversation and was an obnoxiously outspoken vegetarian and feminist by seventh grade.

By the time she got to New York ten years later, she was helping organize politically minded artists, getting involved with prison-reform issues and participating in New York’s famously lefty slam-poetry scene. She was still a vegetarian and a feminist, too, although hopefully less obnoxiously so than she had been in junior high. Erik, on the other hand, liked Slim Jims, teriyaki beef jerky, salami, and sardines.

Jessica’s dragging Erik to an anti-death-penalty conference that February afternoon may have been some sort of subconscious test to see how he’d do around her radical friends—or maybe she just wanted the company. Either way, he showed up, curious and open-minded (and did just fine with her radical friends, thank you very much). The conference took place in the ornately carved chapel at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine and the beige, nondescript lecture halls of Columbia Law School. We shuffled between different workshops all day, discussing the case history of imprisoned writer Mumia Abu-Jamal, the role of artists in creating social change, the new report on the death penalty just released by Columbia University. Finally, we wound up at a workshop that, on the surface, looked similar to the others.

Freshly drawn permanent-marker arrows pointed us into yet another gray-and-tan lecture hall at Columbia Law; we sat down to learn about a group of Illinois men who had been dubbed the Death Row Ten, one of whom was a man named Leonard Kidd. We watched a news segment on the cases and heard a lecture that explained how Kidd’s confession—along with those of the other members of the Death Row Ten—had allegedly been tortured out of him by a police commander named Jon Burge. This wasn’t just rumor or bad propaganda; it had been proven through an internal investigation by the Chicago PD, and an external investigation by Chicago newspapers. Burge, who had learned his “techniques” in Vietnam, had been fired (with pension), but Kidd—with little other evidence against him besides his “confession”—still languished on death row, unable to get a new trial. Needless to say, we were disturbed by this information; but it seemed no different from more bad news in the paper, or an upsetting report on 20/20.

But then the call came through. The workshop organizers had arranged for Leonard Kidd to call their cell phone collect from the prison; the phone was hooked up to a speaker so Leonard could speak directly to the audience. His words hollowed out the room. He tried to control the quavering in his voice. He tried to reach out to us; you could hear it over the bad connection. You could hear his will. And his fear. Within moments, tears were streaming down our faces: here was this young man, trapped in an unbelievably tragic and terrifying situation. Not much older than us, likely innocent, caught in a system he and half a dozen lawyers couldn’t find a way out of, waiting to be put to death for something he didn’t do. Something happened, hearing his voice, right there, in the room, that took our experience out of the realm of newspaper-story, “isn’t-that-terrible” abstraction, and into the realm of human empathy—where it belonged.

Soon, prison authorities got wise to the jerry-rigged phone call, and the line went dead. In the quiet afterward, Erik looked around the room. His distance from the activist “scene” gave him enough perspective to notice that everyone in the room was already an organizer or a defense attorney. They all knew these stories. They were the proverbial choir, being preached to. Moving as it was to hear Leonard speak, they were not the ones who really needed to have this experience. Annoyed and frustrated by this, Erik started writing notes to Jessica about it on her laptop. Soon we were writing back and forth to each other, brainstorming about how to get around the problem.

At first our brainstorms consisted mainly of complaining that people who didn’t already sympathize would never put themselves in a situation where they’d have this kind of experience. Why should they think about it? It’s too depressing. But then we started writing back and forth about what exactly “this kind of experience” was. Were we really only talking about getting people in a room where they would literally hear the voices of the wrongly convicted? Or were there other ways to create the same kind of emotional immediacy with the same kinds of stories? Then the conversation really opened up.

We knew something about how good theater could, if done right, allow an audience member to empathize with someone from completely different circumstances, family background, class, race. And we both were interested in documentary theater, a relatively new form being utilized most notably by Anna Deavere Smith, Moisés Kaufman, Emily Mann, and Eve Ensler. Ideas, words, started to flash back and forth between us. Ensemble piece, monologues, not didactic. Real people’s words. Somehow at the same time, we both arrived at the same idea: What if we found people who had been on death row who were innocent and made a play from their words?

It seemed a perfect way around, no…through all the problems we’d been discussing. A well-constructed play could attract audiences who had no political predisposition to the subject matter. If we did it right, we could bring in audiences with diverse points of view—some people who agreed with us coming in the door, sure, but also people who didn’t, and people who hadn’t previously considered the issue. If we limited our subjects to those who had been on death row—the most extreme, literally life-and-death stories—audiences might attend the play for the dramatic value of the stories alone. And if we kept our focus on cases where people had been declared innocent by the system, then we could sidestep much of the polarized ethical debate that so often bogs down conversations about the death penalty and get right to the human issues involved.

We left the conference energized and set to work doing research. We knew from that first conversation that we wanted to create a documentary play, using the subjects’ real words. We knew we wanted to limit our subject matter to people who had been on death row and who had been found innocent and released by the court system. But beyond that, we were starting from scratch.

Chapter Two

We spent about two months immersed in reading on capital punishment, wrongful conviction, and the legal system in general—which mostly served to show us how little we knew. We’d both gone off to college and studied theater, so the furthest either of us had gotten in any formal study of the court system was our high school government classes.

Erik remembered his government class well: One day in that class, sometime back in the eighties, Erik had participated in a debate about the death penalty. There were about thirty students in the class, and when the teacher asked, “Okay, who here is against the death penalty?” one lone, skinny arm shot up—Erik’s. Then she asked who was in favor of it, and the other twenty-nine arms waved in the air. Erik was, of course, assigned the anti-death-penalty position in the debate, and with the few facts he had at his disposal, he performed valiantly. At the end, the teacher polled the class again. Now, two people were against the death penalty. Erik had reached one person. He tried hard to hold on to the comfort this offered as a couple kids whose minds he hadn’t changed decided it would be fun to engage in a little after-class debate of their own by slamming Erik’s books onto the floor and dumping his backpack in a wastebasket. Jessica had similar experiences as an alienated lefty in high school—she’d paid attention to any political facts she could absorb in class, if only to use them as ammo in heated arguments with the jocks, and her memories of government class were just as vivid.

So from those high school classes—and from reading newspapers in the ensuing years—we thought we understood the American judicial system, at least a little. But our research began to show us that in the real world, things rarely work the way they’re laid out on paper. We both had a lot to learn.

We started way back at the beginning. The death penalty as a legal institution dates back to Hammurabi’s Code, we read; it also shows up in ancient Rome and Athens. The American death penalty’s roots, unsurprisingly, are mostly in British law. The death penalty was implemented fairly rarely in early Britain—until the reign of Henry the Eighth, under whose rule, according to the Death Penalty Information Center, “as many as seventy-two thousand people are estimated to have been executed.” The death penalty remained in heavy use in Britain until around 1873, when it declined in popularity and significant reforms began.

In the meantime, though, British settlers brought the death penalty to America; the earliest recorded execution in the colonies was in 1608. In 1612, according to the Death Penalty Information Center, the governor of Virginia instituted the death penalty for an enormous number of offenses, “such as stealing grapes, killing chickens, and trading with Indians.” Beginning in the late 1700s, American opposition to the death penalty grew in strength and volume; early American advocates of death penalty reform or abolition included Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin. The abolitionist movement gained momentum over the next fifty years: in 1834, Pennsylvania became the first state to ban public executions and began conducting them in correctional facilities (a big move at the time). Over the ensuing two decades, a few states abolished the death penalty for all crimes except treason; around the world, several other countries did the same. At the same time, however, some states increased the use of the death penalty, especially for crimes (sometimes quite minor ones) committed by slaves.

The Progressive Movement brought the first major wave of twentieth-century death penalty reform. Between 1907 and 1917, six additional states abolished the death penalty, and three more strictly limited its application. But then, in the wake of the Russian Revolution, and in light of the serious political challenges being posed by American working classes and socialism, the ruling classes in America started to panic about the possibility of a domestic revolution; a law-and-order mentality prevailed, and the death penalty was reinstated in five of the six abolitionist states. The death penalty remained in heavy use from the 1920s through the 1940s; in the 1930s—during Prohibition and the Depression—there were more executions than in any other decade in American history.

After World War Two, American public support for the death penalty declined again, reaching an all-time low of 42 percent in 1966. At the same time, more countries around the world began to ban the use of the death penalty; in the wake of the Holocaust, international human rights treaties were drafted that declared life to be a basic human right, and over the following three decades, executions all but ceased in the vast majority of the industrialized world. The Supreme Court, citing an “evolving standard of decency,” began to reflect this decline in support for the death penalty, beginning in the late sixties. In 1972, the Court ruled in the landmark Furman v. Georgia decision that the Georgia capital punishment statute (which was similar in kind to most states’ death penalty laws) was “cruel and unusual” and thus violated the Eighth Amendment. This ruling effectively commuted the sentences of 629 death row inmates across the country and suspended the death penalty.

In ruling that the specific death penalty statutes were unconstitutional—rather than the death penalty as a whole—the Court left an opening for states to rewrite their statutes to do away with the problems cited in Furman, and to reinstate the death penalty. The first to do so was Florida; thirty-four other states followed, providing sentencing guidelines that allowed for the introduction of aggravating and mit...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Copyright

- Acknowledgments

- Foreword

- Chapter One

- Chapter Two

- Chapter Three

- Chapter Four

- Chapter Five

- Chapter Six

- Chapter Seven

- Chapter Eight

- Chapter Nine

- Chapter Ten

- Chapter Eleven

- Chapter Twelve

- Chapter Thirteen

- Chapter Fourteen

- Chapter Fifteen

- Chapter Sixteen

- Chapter Seventeen

- Chapter Eighteen

- Chapter Nineteen

- Chapter Twenty

- Chapter Twenty-one

- Afterword