eBook - ePub

Your Money and Your Brain

How the New Science of Neuroeconomics Can Help Make You Rich

- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Drawing on the latest scientific research, Jason Zweig shows what happens in your brain when you think about money and tells investors how to take practical, simple steps to avoid common mistakes and become more successful.

What happens inside our brains when we think about money? Quite a lot, actually, and some of it isn’t good for our financial health. In Your Money and Your Brain, Jason Zweig explains why smart people make stupid financial decisions—and what they can do to avoid these mistakes. Zweig, a veteran financial journalist, draws on the latest research in neuroeconomics, a fascinating new discipline that combines psychology, neuroscience, and economics to better understand financial decision making. He shows why we often misunderstand risk and why we tend to be overconfident about our investment decisions. Your Money and Your Brain offers some radical new insights into investing and shows investors how to take control of the battlefield between reason and emotion.

Your Money and Your Brain is as entertaining as it is enlightening. In the course of his research, Zweig visited leading neuroscience laboratories and subjected himself to numerous experiments. He blends anecdotes from these experiences with stories about investing mistakes, including confessions of stupidity from some highly successful people. Then he draws lessons and offers original practical steps that investors can take to make wiser decisions.

Anyone who has ever looked back on a financial decision and said, “How could I have been so stupid?” will benefit from reading this book.

What happens inside our brains when we think about money? Quite a lot, actually, and some of it isn’t good for our financial health. In Your Money and Your Brain, Jason Zweig explains why smart people make stupid financial decisions—and what they can do to avoid these mistakes. Zweig, a veteran financial journalist, draws on the latest research in neuroeconomics, a fascinating new discipline that combines psychology, neuroscience, and economics to better understand financial decision making. He shows why we often misunderstand risk and why we tend to be overconfident about our investment decisions. Your Money and Your Brain offers some radical new insights into investing and shows investors how to take control of the battlefield between reason and emotion.

Your Money and Your Brain is as entertaining as it is enlightening. In the course of his research, Zweig visited leading neuroscience laboratories and subjected himself to numerous experiments. He blends anecdotes from these experiences with stories about investing mistakes, including confessions of stupidity from some highly successful people. Then he draws lessons and offers original practical steps that investors can take to make wiser decisions.

Anyone who has ever looked back on a financial decision and said, “How could I have been so stupid?” will benefit from reading this book.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Your Money and Your Brain by Jason Zweig in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Personal Development & Personal Finance. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Personal DevelopmentSubtopic

Personal FinanceCHAPTER ONE

Neuroeconomics

BRAIN, n. An apparatus with which we think that we think.

—Ambrose Bierce

“HOW COULD I HAVE BEEN SUCH AN IDIOT?” IF YOU’VE never yelled that sentence at yourself in a fury, you’re not an investor. There may be nothing across the entire spectrum of human endeavor that makes so many smart people feel so stupid as investing does. That’s why I’ve set out to explain, in terms any investor can understand, what goes on inside your brain when you make decisions about money. To get the best use out of any tool or machine, it helps to know at least a little about how it works; you will never maximize your wealth unless you can optimize your mind. Fortunately, over the past few years, scientists have made stunning discoveries about the ways the human brain evaluates rewards, sizes up risks, and calculates probabilities. With the wonders of imaging technology, we can now observe the precise neural circuitry that switches on and off in your brain when you invest.

I’ve been a financial journalist since 1987, and nothing I’ve ever learned about investing has excited me more than the spectacular findings emerging from the study of “neuroeconomics.” Thanks to this newborn field—a hybrid of neuroscience, economics, and psychology—we can begin to understand what drives investing behavior not only on the theoretical or practical level, but as a basic biological function. These flashes of fundamental insight will enable you to see as never before what makes you tick as an investor.

On this ultimate quest for financial self-knowledge, I’ll take you inside laboratories run by some of the world’s leading neuroeconomists and describe their fascinating experiments firsthand, since I’ve had my own 1 brain studied again and again by these researchers. (The scientific consensus on my cranium is simple: It’s a mess in there.)

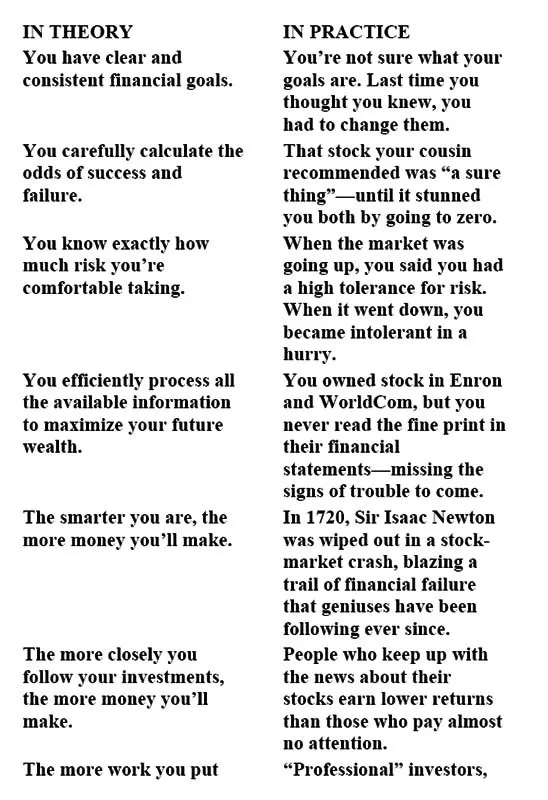

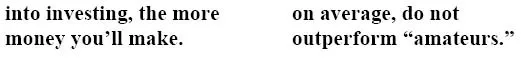

The newest findings in neuroeconomics suggest that much of what we’ve been told about investing is wrong. In theory, the more we learn about our investments, and the harder we work at understanding them, the more money we will make. Economists have long insisted that investors know what they want, understand the tradeoff between risk and reward, and use information logically to pursue their goals.

In practice, however, those assumptions often turn out to be dead wrong. Which side of this table sounds more like you?

You’re not alone. Like dieters lurching from Pritikin to Atkins to South Beach and ending up at least as heavy as they started, investors habitually are their own worst enemies, even when they know better.

One of the themes of this book is that our investing brains often drive us to do things that make no logical sense—but make perfect emotional sense. That does not make us irrational. It makes us human. Our brains were originally designed to get more of whatever would improve our odds of survival and to avoid whatever would worsen the odds. Emotional circuits deep in our brains make us instinctively crave whatever feels likely to be rewarding—and shun whatever seems liable to be risky.

To counteract these impulses from cells that originally developed tens of millions of years ago, your brain has only a thin veneer of relatively modern, analytical circuits that are often no match for the blunt emotional power of the most ancient parts of your mind. That’s why knowing the right answer, and doing the right thing, are very different.

In short, the investing brain is far from the consistent, efficient, logical device that we like to pretend it is. Even Nobel Prize winners fail to behave as their own economic theories say they should. When you invest—whether you are a professional portfolio manager overseeing billions of dollars or a regular Joe with $60,000 in a retirement account—you combine cold calculations about probabilities with instinctive reactions to the thrill of gain and the anguish of loss.

The 100 billion neurons that are packed into that three-pound clump of tissue between your ears can generate an emotional tornado when you think about money. Your investing brain does not just add and multiply and estimate and evaluate. When you win, lose, or risk money, you stir up some of the most profound emotions a human being can ever feel. “Financial decision-making is not necessarily about money,” says psychologist Daniel Kahneman of Princeton University. “It’s also about intangible motives like avoiding regret or achieving pride.” Investing requires you to make decisions using data from the past and hunches in the present about risks and rewards you will harvest in the future—filling you with feelings like hope, greed, cockiness, surprise, fear, panic, regret, and happiness. That’s why I’ve organized this book around the succession of emotions that most people pass through on the psychological roller coaster of investing.

For most purposes in daily life, your brain is a superbly functioning machine, instantly steering you away from danger while reliably guiding you toward basic rewards like food, shelter, and love. But that same intuitively brilliant machine can lead you astray when you face t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Dedication

- Chapter 1: Neuroeconomics

- Chapter 2: “Thinking” and “Feeling”

- Chapter 3: Greed

- Chapter 4: Prediction

- Chapter 5: Confidence

- Chapter 6: Risk

- Chapter 7: Fear

- Chapter 8: Surprise

- Chapter 9: Regret

- Chapter 10: Happiness

- Appendix 1

- Appendix 2

- Appendix 3

- Notes

- Acknowledgments

- Index

- Photographic Insert

- Copyright