- 336 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

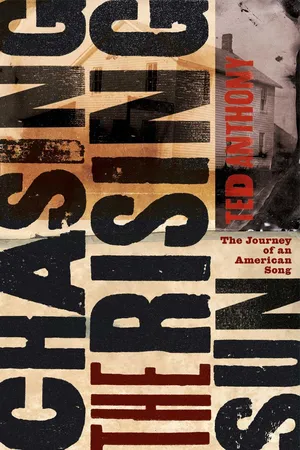

Chasing the Rising Sun is the story of an American musical journey told by a prize-winning writer who traced one song in its many incarnations as it was carried across the world by some of the most famous singers of the twentieth century.

Most people know the song "House of the Rising Sun" as 1960s rock by the British Invasion group the Animals, a ballad about a place in New Orleans -- a whorehouse or a prison or gambling joint that's been the ruin of many poor girls or boys. Bob Dylan did a version and Frijid Pink cut a hard-rocking rendition. But that barely scratches the surface; few songs have traveled a journey as intricate as "House of the Rising Sun."

The rise of the song in this country and the launch of its world travels can be traced to Georgia Turner, a poor, sixteen-year-old daughter of a miner living in Middlesboro, Kentucky, in 1937 when the young folk-music collector Alan Lomax, on a trip collecting field recordings, captured her voice singing "The Rising Sun Blues." Lomax deposited the song in the Library of Congress and included it in the 1941 book Our Singing Country. In short order, Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger, Lead Belly, and Josh White learned the song and each recorded it. From there it began to move to the planet's farthest corners. Today, hundreds of artists have recorded "House of the Rising Sun," and it can be heard in the most diverse of places -- Chinese karaoke bars, Gatorade ads, and as a ring tone on cell phones.

Anthony began his search in New Orleans, where he met Eric Burdon of the Animals. He traveled to the Appalachians -- to eastern Kentucky, eastern Tennessee, and western North Carolina -- to scour the mountains for the song's beginnings. He found Homer Callahan, who learned it in the mountains during a corn shucking; he discovered connections to Clarence "Tom" Ashley, who traveled as a performer in a 1920s medicine show. He went to Daisy, Kentucky, to visit the family of the late high-lonesome singer Roscoe Holcomb, and finally back to Bourbon Street to see if there really was a House of the Rising Sun. He interviewed scores of singers who performed the song. Through his own journey he discovered how American traditions survived and prospered -- and how a piece of culture moves through the modern world, propelled by technology and globalization and recorded sound.

Most people know the song "House of the Rising Sun" as 1960s rock by the British Invasion group the Animals, a ballad about a place in New Orleans -- a whorehouse or a prison or gambling joint that's been the ruin of many poor girls or boys. Bob Dylan did a version and Frijid Pink cut a hard-rocking rendition. But that barely scratches the surface; few songs have traveled a journey as intricate as "House of the Rising Sun."

The rise of the song in this country and the launch of its world travels can be traced to Georgia Turner, a poor, sixteen-year-old daughter of a miner living in Middlesboro, Kentucky, in 1937 when the young folk-music collector Alan Lomax, on a trip collecting field recordings, captured her voice singing "The Rising Sun Blues." Lomax deposited the song in the Library of Congress and included it in the 1941 book Our Singing Country. In short order, Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger, Lead Belly, and Josh White learned the song and each recorded it. From there it began to move to the planet's farthest corners. Today, hundreds of artists have recorded "House of the Rising Sun," and it can be heard in the most diverse of places -- Chinese karaoke bars, Gatorade ads, and as a ring tone on cell phones.

Anthony began his search in New Orleans, where he met Eric Burdon of the Animals. He traveled to the Appalachians -- to eastern Kentucky, eastern Tennessee, and western North Carolina -- to scour the mountains for the song's beginnings. He found Homer Callahan, who learned it in the mountains during a corn shucking; he discovered connections to Clarence "Tom" Ashley, who traveled as a performer in a 1920s medicine show. He went to Daisy, Kentucky, to visit the family of the late high-lonesome singer Roscoe Holcomb, and finally back to Bourbon Street to see if there really was a House of the Rising Sun. He interviewed scores of singers who performed the song. Through his own journey he discovered how American traditions survived and prospered -- and how a piece of culture moves through the modern world, propelled by technology and globalization and recorded sound.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Chasing the Rising Sun by Ted Anthony in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Music. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Way-Back Machine

I’m the man that signed the contract to raise the rising sun. And that was the biggest thing that man has ever done.

—WOODY GUTHRIE

Sometimes I live in the country; sometimes I live in town.

—LEAD BELLY, “IRENE”

Somewhere in the hills where North Carolina, Tennessee, Kentucky, and Virginia meet sits The Village.

It’s not a real town—at least, not the kind of reality we’re accustomed to. Yet The Village defies logic and exists nonetheless. It lives outside of time and space. It’s a place where possibilities—unsettling possibilities—dwell.

The Village is located in an American Oz of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, a land of the imagination that is deeply of us and yet almost biblical in its longing and death and sacrifice and guilt and innocence and the sheer size of its myths. It is populated by ramblers and drunkards and rounders and vanquished Confederates and doomed train engineers, by two dead presidents named Garfield and McKinley and their assassins, by young women condemned to die at the hands of their lovers by knife or by smoking revolver or by flowing waters over and over again, each time a different voice sings the songs of their sad ends.

If The Village had a telephone directory (and it would be an early, wooden telephone for sure), it would list people immortalized in songs sung long ago, men and women named Willie and Polly and Tom and Omie and Little Sadie and Laura Foster, Sheriff Thomas Dell and Charles Guiteau and Darling Corey and John Henry and John Hardy and Stagolee. Some of its citizens have real-world counterparts, mirror-universe doppelgangers that resemble them but are different in fundamental ways. Some, like Barbara Allen, are kernels of English memories accentuated by centuries of American folk-song buildup. Dying cowboys and blind children and steel-drivin’ men and roving gamblers and desperate men locked in the walls of prison listening to the locomotive whistle blowing or simply looking down that lonesome road. In and around The Village, the places of song wink in and out of our reality: Birmingham Jail and Jericho and Penny’s Farm and Carroll County and Hazard County and the Banks of the Ohio and the depot where you catch the Wabash Cannonball, all teeming with poor boys and girls who leave their little mountain communities, bound for the city and its pleasures and ruinations, doomed to spend the rest of their wicked lives beneath places like the Rising Sun.

In The Village, many things—wonderful things, ugly things, things of magic—are always about to happen. Religion, folk belief, and a uniquely American, uniquely Christian paganism have created this enchanted land. In the pines, in the pines, where the sun never shines. Just as Dorothy wasn’t sure exactly where Kansas ended and Oz began, so it is with The Village. Reality provides the raw material for legend, and legend repays it by bleeding back into reality. The Village has no physical boundaries, only songs and the stories they contain.

The roads that lead out of The Village—and the railroads, always the railroads-sweep south through the Appalachian Mountains, the Blue Ridges, the Smokies, the Cumberlands, winding all the way down past Nashville to the Mississippi Delta, where Robert Johnson did or didn’t sell his soul to the devil at the crossroads of Highways 49 and 61 in exchange for the ability to play some superhuman guitar. They cut west into the Ozarks and south into Georgia, winding through settlements that are long forgotten or were never really noticed at all. All roads end down in New Orleans, where the train and the riverboat carried the runoff of human rambling and tragedy and it pooled in one glorious city of gluttony and racial mixing and fighting and drinking and sex.

Across this land, magic and music blend—British balladry, old-time Baptist hymnody, early Tin Pan Alley songwriting, and West African field hollers that, carried on the backs of slaves and their freed descendants, convulsed forward into the blues with the erratic abruptness of a teenager learning to drive a stick shift. The exuberance of song is palpable, yet always tempered by the melancholy of the worried man. I am a man of constant sorrow; I’ve seen trouble all my days.

These notions of an “other place” had careened through my head since long before the Rising Sun entered my life. But I could never articulate the images that danced at the corners of my vision until I read Greil Marcus’s Invisible Republic: Bob Dylan’s Basement Tapes. Marcus is a music critic, among other things, but using that label is a bit like describing Abraham Lincoln as a federal employee. In tracing the genesis of Bob Dylan’s famed 1967 sessions with the Band—and of Dylan himself—Marcus not only sees this other America but also becomes its master cartographer. He charts its landscape like an existentialist urban-studies guru exploring an alternate universe that many of us Casey Kasem-weaned, Orange Julius-gulping, Styx-listening, Original Recipe-scarfing Americans never begin to encounter.

The music of The Village and the Invisible Republic around it—for I was certain, upon reading Marcus’s book, that his republic was home to my Village—was heard by few until the early 1920s. Then, suddenly, “hillbilly” and “race” recordings began to capture it, amplify it, broadcast it across the land for the first time. Subcultures that had gone ignored or stereotyped for generations by outworlders like me could suddenly hitch their traditions to modernism’s speeding wagon and tell their stories in their own voices. And people were listening. It was a revolution of the ear, but a revolution nonetheless. Marcus writes:

For the first time, people from isolated, scorned, forgotten, disdained communities and cultures had the chance to speak to each other and to the nation at large. A great uproar of voices that were at once old and new was heard, as happens only occasionally in democratic cultures—but always, when it happens, with a sense of explosion, of energies contained for generations bursting out all at once.

Marcus, in turn, credits Harry Smith as the original mapmaker, the wizard of this Oz. Smith was the iconoclast who, in 1952, cobbled together dozens of old 78s from the 1920s and 1930s—tunes that came straight from The Village and the Invisible Republic—and issued them in an astonishing (and legally dubious) multirecord set called The Anthology of American Folk Music. It became one of the foundations of the American folk revival. It’s great fun to read Smith’s quirky liner notes, which feature headlines for songs, as if The Village published its own newspaper. The creatively spelled “Charles Giteau,” about the president killer, is summed up this way: “Assassin of President Garfield Recalls Exploit in Scaffold Peroration.” And the synopsis of “Stackalee” reads like a police blotter: “Theft of Stetson Hat Causes Deadly Dispute, Victim Identifies Self as Family Man.”

Listening to Smith’s Anthology from the distant vantage point of the early twenty-first century, it’s easy to underestimate it or dismiss it as cliché. So much of the material feels familiar. But that’s only because musicians like the Grateful Dead, the Rolling Stones, and Dylan made it their own, and it has wended in and out of rock and pop ever since—as has this notion of a somehow different world. Dylan himself reflected on the place in his 2004 autobiography: “I had already landed in a parallel universe … with more archaic principles and values; one where actions and virtues were old style and judgmental things came falling out on their heads,” he wrote. “It was all there and it was clear—ideal and God-fearing—but you had to go find it.”

In 1952, many of the old-time artists who made the recordings were still alive and had gone back to their jobs in mills and lumberyards and coal mines. The Anthology was a thunderclap from another era that had been forgotten. A good portion of the Anthology’s artists, Marcus writes, “were only twenty or twenty-five years out of their time; cut off by the cataclysms of the Great Depression and the Second World War, and by a national narrative that had never included their kind, they appeared now like visitors from another world, like passengers on a ship that had drifted into the sea of the unwritten.”

Smith’s accomplishment was so starkly bizarre because the old, weird America—as Invisible Republic was renamed in subsequent printings—had been steamrolled by modernism. This was lamented as early as 1919, when Sherwood Anderson published Winesburg, Ohio, his melancholy chronicle of an Ohio town grappling with the encroachment of the modern world.

The coming of industrialism, attended by all the roar and rattle of affairs, the shrill cries of millions of new voices that have come among us from over seas, the going and coming of trains, the growth of cities, the building of the interurban car lines that weave in and out of towns and past farmhouses, and now in these later days the coming of the automobiles has worked a tremendous change in the lives and in the habits of thought of our people of Mid-America…. Much of the old brutal ignorance that had in it also a kind of beautiful childlike innocence is gone forever.

Brutal ignorance and childlike innocence—the murder ballad and the love song, two sides of the same Morgan silver dollar—defined that other America. Now that country—the one beyond the Wal-Marts, the interstate exits, and the chain motels—exists only in pockets, a few geographic but most of them psychological. Somewhere in there, beyond the limited-access highways and the clusters of backlit plastic that represent our tacit agreement of national commerce, a story was lurking. It was the story of a single song and the many routes it had traveled. I was aiming to find it.

We like to believe there is a single, comprehensible world that we all share. Go to work, run to the store, pay the bills, order a Double Whopper with cheese at the drive-thru, drink a PBR at the roadside bar, stop at a freeway exit and fill the tank. It’s a default point of view: We each eat, drink, sing, dance, make love, make children, and die on the same planet, so we must be sharing the world, right? This is the notion that keeps us sane from day to day and also pits us against each other: red state/blue state, black/white, urban/rural, American/foreign. We’re all jostling for physical and cultural space because there’s only one world, and we have to share.

I once believed that. I was wrong.

There are moments in our lives when doors slide open silently, when glimpses of other worlds are served up unexpectedly. Sometimes we choose to pass through the doors and explore. More often we don’t; the doors beckon us and we move on, blissfully unaware, because the cataract has already obscured the lens.

The door that changes my life, that shows me one of these alternate worlds, slides open on a sunny afternoon in July 1998 in Keene, New Hampshire, in the semidarkness of a restaurant called the Thai Garden.

On this day, I am sitting in the restaurant with a lovely blonde named Melissa, who has recently become—to my somewhat stunned surprise—my girlfriend. This is one of our first trips together. The blonde does not know of my tendency for weird obsessions. She does not know that, during the summer of 1989, I ate beef MexiMelts at Taco Bell for three months straight. Or that, in college, I played the Grateful Dead song “A Touch of Grey” so many times in the stereo of the Delta Chi house at Penn State that my fraternity brothers absconded with the cassette and melted it. The blonde does not know that when I developed a nursery school crush, I sat on the floor of my room with my mother’s Olympia manual typewriter and typed the little girl’s name over and over. Sharon Simmons. Sharon Simmons. Sharon Simmons.

The blonde knows none of this. She is not yet my wife, not yet the mother of a boy who carries my name, not yet the partner of a man who will spend more than $10,000 chasing a song around the world. She does not know that she will offer to spend her honeymoon driving through Southern backroads stopping at dimly lit roadhouses and listening to country music. She is blissfully unaware that in two years, I will drag her through the sweaty streets of Bangkok after midnight, looking for an air-conditioned karaoke bar that will give me the opportunity to sing a song, just one song. That song.

She knows only that she wants to order, and that there is a small disturbance at the next table.

The couple next to us is speaking loudly and barking at the staff. Why, the man demands, isn’t sweet-and-sour pork on the menu? I want to grab him by his lapels and tell him that sweet-and-sour pork is Chinese, for chrissake, and barely that to boot. But Melissa and I tune them out. The only distraction is the background music, and we begin to listen.

Background music is a subtle but ever-present part of our lives as consumers. It is calibrated to set a mood, grease the wheels, get the wallet out and—in many cases—to not be noticed. Usually, the mood and flavor of the music matches the surroundings.

Not here.

The tune is mellow, designed to insinuate itself unobtrusively. It sounds vaguely familiar, as if a memory of a memory: a minor key, lots of sweeping notes. We realize we should know this song. But its journey has been a winding one. By the time it arrives at this place, at this moment, watered down and stripped of its pain, it has become almost unrecognizable.

“I’ve heard it a million times. I just can’t think of the name,” Melissa says.

Somehow, a kernel of distinctiveness bursts through. It is a piece of music that the world came to know in the 1960s, in a version full of electric instrumentals topped off by a British bluesman’s voice. It embedded itself in that subconscious, collective musical memory that we Americans accumulate through years of absorbing cultural background noises, lifetimes of listening to drive-time DJs and weekly Top 40s.

The song is “House of the Rising Sun.”

Even in mellow background music, the words are implied: There is a house in New Orleans … been the ruin of many a poor boy … mother was a tailor … gambling man … suitcase and a trunk … mothers tell your children … not to do what I have done … wear that ball and chain. In my mind, I hear what I will come to know as the definitive version—the switchblade of a voice that came from Eric Burdon, front man for the Animals, the British band that made the song an unorthodox chart-topper in 1964.

On a balmy evening in 1998, a composition that began life somewhere in the South more than a century ago—that has been globalized and cannibalized, repackaged and rerecorded—is being presented to us as window dressing as we order our tom yum soup.

I don’t believe in epiphanies; they’re usually simplistic answers to complicated questions. But for some reason, a revelation hits: The story of this song, how it got from someone’s front porch to a Southeast Asian restaurant in upper New England, is more than an interesting anecdote. It is about technology, globalization, packaging, marketing, and the rise of recorded sound. It is the story of American culture in the twentieth century.

We are taught that drama must be Very Dramatic, that those who shout the loudest have the most important stories to tell. Occasionally, men like Charles Kuralt or Alistair Cooke pass our way and show us that regular Americans are fascinating, too, but we seem to endorse the fifty-foot-billboard rule of human importance. Yet many stories of our age are more subtle and may not involve Schwarzenegger-style theatrics. Instead, they unfold in small towns, along lonely highways, in Midwestern apartment complexes and in rickety Southern shacks. In suburbs and office parks and rowhouses and tenements. Or in Yankee-land Thai restaurants with Buddhas kneeling at the door, even.

Rarely is human obsession obvious at the outset. It is born as a seed of curiosity and only later does it grow into an out-of-control beanstalk. But I should have seen this one coming.

I have always been fascinated with history and with charting connections between the worlds of yesterday and the lives of today—particularly when it comes to America. This comes from something very basic: My full name is Edward Mason Anthony IV, which means that there are Edward Mason Anthonys going back to 1826 in my family. The Anthony side of my family followed the epic sweep of early American history—immigration to New England in colonial times, enlistment in the Revolutionary War, migration west to upstate New York, then to Ohio and, finally, for some Anthonys, further west. I have been able to see how the events I learned about in high school history class played out in my own family and I have seen two gravestones with my own name on them. When I was growing up, my obsession was visiting old courthouses, scouring dusty archives, tromping through lichen-coated graveyards looking for distant ancestors. I was seeking proof, I think, that the people who came before me had actually lived real lives, that they were more than paper and microfilm and memories. Such experiences made the past more personal, more vivid, rather than something that belonged only to another world.

Now I had another obsession, and it would become a global one that expanded far beyond anything I ever expected. Before it was over, I would buy nearly five hundred CDs and more than two hundred books. I would stay in dozens of cheap motels as I traversed the American landscape and put close to ten thousand miles on various vehicles. I would eat far too much fast food and fill the floors of rental-car backseats with empty Diet Coke bottles and piles of greasy plastic packaging—from Slim Jim wrappers to pork rind bags. I would chase the song into Southeast Asian karaoke bars, through music stores in the frigid plateaus near the China-Russia border, and across the Blue Ridge and Smoky mountains. I would ask people about it while eating raw oysters in New Orleans, smoking cheap cheroots in Nashville, and gulping down pints of obscure bitter ales in an English seashore town. The search would consume me for years. And when I asked myself why, I would always come back to one answer: It was something small that connected to something much larger—to everything, really. It contained infinite chances for new knowledge, new experiences, and a fresh understanding of the world.

In my favorite Dr. Seuss book, McElligot’s Pool, a boy goes fishing in a tiny pond and is scorned by a farmer. “You’ll never catch fish in McElligot’s Pool,” the man scoffs. Then the lens pulls back. The pool in the distant meadow is connected—to an underground brook, to a river through the city, to the vast ocean and beyond. The tiniest of places is always touching the biggest, and things flow back and forth. I always loved that book as a child but never knew quite why. Now I do.

Connections mean stories. One person, alone in one place, is a small story. When people connect, when their connections produce new ideas and more connections, things get interesting. Stories multiply. That was what had happened with “House of the Rising Sun,” I was sure: all these human interactions, quietly hidden in the overproduced notes of background music in the unlikeliest of places.

It could have been anything—a recipe, a folktale, an advertising logo drawn from tradition, a quaint saying that reaches back to Elizabethan England and beyond. But it wasn’t. For me, it was this song. The connections were dancing right in front of me. Where had this song come from? Where had it gone? Who carried it there?

Quietly, the door had opened. My life had changed, and I was fortunate to r...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Introduction

- Prologue The Moment

- 1 The Way Back Machine

- 2 Bubbling Up

- 3 From the Folkways …

- 4 … To the Highways

- 5 Blast Off

- 6 Everywhere

- 7 Diaspora

- 8 Family

- 9 Going Back to New Orleans

- Afterword My Race Is Almost Run …

- Notes

- Further Reading

- Selected Discography

- Acknowledgments

- Index

- About the Author