eBook - ePub

Applebee's America

How Successful Political, Business, and Religious Leaders Connect with the New American Community

- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Applebee's America

How Successful Political, Business, and Religious Leaders Connect with the New American Community

About this book

In this era of technology, terror, and massive social change, it takes a deft touch to connect with Americans. Applebee's America cracks the twenty-first-century code for political, business, and religious leaders struggling to keep pace with the times.

A unique team of authors -- Douglas B. Sosnik, a strategist in the Clinton White House; Matthew J. Dowd, a strategist for President Bush's two campaigns; and award-winning political journalist Ron Fournier -- took their exclusive insiders' knowledge far outside Washington's beltway in search of keys to winning leadership.

They discovered that successful leaders, even those from disparate fields, have more in common than not.

Their book takes you inside the reelection campaigns of Bush and Clinton, behind the scenes of hyper-successful megachurches, and into the boardrooms of corporations such as Applebee's International, the world's largest casual dining restaurant chain. You'll also see America through the anxious eyes of ordinary people, buffeted by change and struggling to maintain control of their lives.

Whether you're promoting a candidate, a product, or the Word of God, the rules are the same in Applebee's America.

• People make choices about politics, consumer goods, and religion with their hearts, not their heads.

• Successful leaders touch people at a gut level by projecting basic American values that seem lacking in modern institutions and missing from day-to-day life experiences.

• The most important Gut Values today are community and authenticity. People are desperate to connect with one another and be part of a cause greater than themselves. They're tired of spin and sloganeering from political, business, and religious institutions that constantly fail them.

• A person's lifestyle choices can be used to predict how he or she will vote, shop, and practice religion. The authors reveal exclusive new details about the best "LifeTargeting" strategies.

• In this age of skepticism and media diversification, people are abandoning traditional opinion leaders for "Navigators." These otherwise average Americans help their family, friends, neighbors, and coworkers negotiate the swift currents of change in twenty-first-century America.

• Winning leaders ignore conventional wisdom and its many myths, including these false assumptions: Voters only act in their self-interests; Republicans rule exurbia; and technology drives people apart. Wrong, wrong, and wrong.

• Once you squander a Gut Values Connection, you may never get it back. Bush learned that hard lesson within a year of winning reelection.

Applebee's America offers numerous practical examples of how leaders -- whether from the worlds of politics, business, or religion -- earn the loyalty and support of people by understanding and sharing their values and goals.

A unique team of authors -- Douglas B. Sosnik, a strategist in the Clinton White House; Matthew J. Dowd, a strategist for President Bush's two campaigns; and award-winning political journalist Ron Fournier -- took their exclusive insiders' knowledge far outside Washington's beltway in search of keys to winning leadership.

They discovered that successful leaders, even those from disparate fields, have more in common than not.

Their book takes you inside the reelection campaigns of Bush and Clinton, behind the scenes of hyper-successful megachurches, and into the boardrooms of corporations such as Applebee's International, the world's largest casual dining restaurant chain. You'll also see America through the anxious eyes of ordinary people, buffeted by change and struggling to maintain control of their lives.

Whether you're promoting a candidate, a product, or the Word of God, the rules are the same in Applebee's America.

• People make choices about politics, consumer goods, and religion with their hearts, not their heads.

• Successful leaders touch people at a gut level by projecting basic American values that seem lacking in modern institutions and missing from day-to-day life experiences.

• The most important Gut Values today are community and authenticity. People are desperate to connect with one another and be part of a cause greater than themselves. They're tired of spin and sloganeering from political, business, and religious institutions that constantly fail them.

• A person's lifestyle choices can be used to predict how he or she will vote, shop, and practice religion. The authors reveal exclusive new details about the best "LifeTargeting" strategies.

• In this age of skepticism and media diversification, people are abandoning traditional opinion leaders for "Navigators." These otherwise average Americans help their family, friends, neighbors, and coworkers negotiate the swift currents of change in twenty-first-century America.

• Winning leaders ignore conventional wisdom and its many myths, including these false assumptions: Voters only act in their self-interests; Republicans rule exurbia; and technology drives people apart. Wrong, wrong, and wrong.

• Once you squander a Gut Values Connection, you may never get it back. Bush learned that hard lesson within a year of winning reelection.

Applebee's America offers numerous practical examples of how leaders -- whether from the worlds of politics, business, or religion -- earn the loyalty and support of people by understanding and sharing their values and goals.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part I

Great Connectors

1

Politics:

Values Trump the Economy

His 1840 campaign plan divided the party organization into three levels of command. The county captain was to “procure from the poll-books a separate list for each precinct” of everyone who had previously voted the Whig slate. The list would then be divided by each precinct captain “into sections of 10 who reside most convenient to each other.” The captain of each section would then be responsible to “see each man of his section face to face and procure his pledge…[to] vote as early on the day as possible.”

—DORIS KEARNS GOODWIN, Team of Rivals:

The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln

The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln

IN 2000, the nation was at peace, the economy was booming, and President Clinton’s approval rating stood at 62 percent. The odds were stacked against Texas Governor George W. Bush in his bid to defeat Clinton’s vice president, Al Gore. One day at Bush headquarters in Austin, Texas, his media adviser, Mark McKinnon, blurted out a perfectly facetious campaign slogan: “Everything’s going great. Time for a change.” It became a running joke inside the Bush team.

Four years later, the nation was mired in an unpopular war, the economy was slumping, and President Bush’s approval rating had dipped to 46 percent. No president had ever been reelected with such a low number. This time, his strategist Matthew Dowd put a sardonic twist on McKinnon’s line: “Everything sucks. Stay the course” was the 2004 rallying cry.

President Bush twice defied conventional wisdom and won national elections. We’re going to tell you how. But we’re not going to stop there. We’re also going to explain how President Clinton battled back from political irrelevancy to win reelection in 1996. Despite their different ideologies, these two men had strikingly similar approaches to making and maintaining Gut Values Connections.

First, they recognized changes in the political marketplace and adapted. For President Clinton, that required expanding his appeal to “swing voters” (independent-minded folks who bounce between the parties) after being elected with just 43 percent of the vote in 1992. For President Bush, it was the determination that there were not enough swing voters to make a difference in 2004 and that his reelection hopes hinged on finding passive and inactive Republicans.

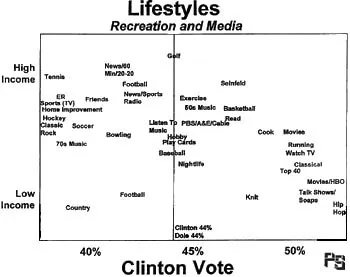

Second, both presidents blended cutting-edge polling and consumer research strategies to target potential voters based on how they live. A voter who played tennis and watched ER was pegged by President Clinton’s team as a supporter of his Republican opponent, Bob Dole. Another who watched basketball and public television was considered a Democrat. If the Clinton plan had been the equivalent of LifeTargeting 1.0, President Bush’s advisers created LifeTargeting 4.0—a quantum leap that allowed them to track millions of voters based on their confidential consumer histories. If you’re a voter living in one of the sixteen states that determined the 2004 election, the Bush team had your name on a spreadsheet with your hobbies and habits, vices and virtues, favorite foods, sports, and vacation venues, and many other facts of your life.

President Clinton’s reelection team predicted political behavior based on a person’s recreation and media habits.

Presidents Bush and Clinton also found new ways to talk to people. For the Clinton team, that meant identifying where the swing voters lived and basing presidential travel and paid advertising decisions on their whereabouts. President Bush’s advisers devised a formula that estimated how many Republicans watched every show on TV. They also revolutionized word-of-mouth marketing for politics and the use of Navigators—society’s new opinion leaders helping Americans navigate what Lincoln called the “stormy present.” Both presidents were innovators in the use of niche TV and radio ads.

Though wildly successful in 1996, President Clinton’s playbook was out of date by 2004. President Bush’s reelection strategies were breakthrough two years ago, but they will be stale by the next presidential election. Great Connectors like Presidents Bush and Clinton adapt to the times.

They also realize that tactics do not win elections. Gut Values do. Cutting-edge strategies are useful only when they help a candidate make his or her values resonate with the public. For all their faults (and they had their share), Presidents Bush and Clinton knew that their challenge was in appealing to voters’ hearts, not their heads. We heard this countless times: “Sure, he had sex with an intern and lied about it, but he cares about me and is working hard on my behalf.” And this: “The Iraq war stinks and his other policies aren’t so hot, but at least I know where he stands.”

Even as the war in Iraq grew unpopular in 2004, President Bush’s unapologetic antiterrorism policies seemed to most voters to reflect strength and principled leadership—two Gut Values that kept him afloat until mid-2005, when he lost touch with the values that had gotten him reelected. Even after lying to the public about his affair with a White House intern, President Clinton never lost his image as an empathetic, hardworking leader—the foundation of his Gut Values Connection.

Both presidents understood that the so-called values debate runs deeper than abortion, gay rights, and other social issues that are too often the focus of the political elite in Washington. Voters don’t pick presidents based on their positions on a laundry list of policies. If they did, President Bush wouldn’t have stood a chance against Al Gore in 2000 or John Kerry in 2004. Rather, policies and issues are mere prisms through which voters take the true measure of a candidate: Does he share my values?

For those Democratic leaders, including Kerry himself, who whined and wondered why people “voted against their self-interests” in 2004, here’s your answer: the voters’ overriding interest is to elect leaders who reflect their values even when, as in 2004, the Gut Values candidate (Bush) fared poorly in polls on the economy, health care, Social Security, the war in Iraq, and other top issues. These are not selfish times. Americans are not selfish people. A quarter century ago, Ronald Reagan asked, “Are you better off today than you were four years ago?” That was an effective question in 1980, but more relevant ones today would be: Is your country better off? Is your family better off? How about your community? Voters are looking for leaders to speak to those questions—those Gut Values.

Today, two Gut Values dominate the political landscape. Success will come to any leader who appeals to the public’s desire for community and authenticity. President Bush’s team knitted existing social networks into a political operation that fed on people’s desire to be part of something, anything—preferably a cause greater than themselves. Democratic presidential candidate Howard Dean created communities on the Internet and exploited them in 2004, a topic for chapter 5.

Authenticity is a valued commodity in the political marketplace because Americans have been subjected to years of failure, scandal, and butt-covering by institutions that are suppose to help them prosper. From the Vietnam War, Watergate, Iran-contra, and President Clinton’s impeachment to runaway deficits, soaring health care costs, and Hurricane Katrina, voters have been fed a steady diet of corruption and incompetence in government. Business scandals at the turn of the millennium soured the public on corporate America. The unseemly excesses of TV evangelism, the Catholic Church’s sex abuse scandals, and wrongdoing at several charitable organizations challenged the public’s faith in private institutions.

Tired of the lies and half-truths, people are more jaded than ever. They’re also better educated and better informed than in the past, which helps them spot a phony. Americans don’t expect their leaders to be perfect, but they want them to be perfectly frank: to acknowledge their mistakes, promise to fix the problem, and then actually fix it. This we learned from President Bush in 2005: when a politician loses his credibility, voters start to question his other values and eventually start looking at his policies differently. In politics, this can be doom.

To explore the shifting political landscape fully, we’ll keep taking you back to a table at an Applebee’s restaurant in exurban Detroit, where two middle-class women named Debbie Palos and Lynn Jensen explained how their political inclinations changed after they became mothers and moved to a Republican-dominated exurb.

When you get done with this chapter, you’ll see that while the playing field has tilted toward the GOP in recent years, neither party has cornered the market on “Applebee’s America.”

Swing Voters

HOWELL, Mich.—Debbie Palos is a prochoice nurse and the daughter of a Teamster who cast her first two presidential ballots for Clinton. Her friend and neighbor Lynn Jensen supports abortion rights, opposes privatization of Social Security, and thinks President Clinton was the last president “who gave a hoot about the middle class.”

They’re lifelong Democrats, just like their parents. Economically, the Hartland, Michigan, women and their families fared better in the 1990s than they have so far in this decade. Both opposed the war in Iraq.

Yet they both voted for President Bush in 2004.

“I didn’t like doing it, but the other guy was too radical for me,” says Jensen, a thirty-three-

year-old mother of two. She scoops a spoonful of rice from her plate into the mouth of her fourteen-month-old daughter, Ryan.

year-old mother of two. She scoops a spoonful of rice from her plate into the mouth of her fourteen-month-old daughter, Ryan.

Across the polished wood table at their local Applebee’s, Palos picks at a steak salad, enjoying lunch with Jensen while her nine-year-old boy and six-year-old girl are in school.

“I just don’t think much of Democrats anymore,” says Palos. “Besides, I may not agree with President Bush on everything, but at least I know he’s doing what he thinks is right.”

President Clinton

Adapting

Doug Sosnik was summoned to the Oval Office for a job interview. Actually, it was more of an introduction. Clinton’s adviser Harold Ickes had already assured Sosnik that he had it wired and Sosnik would be White House political director after a perfunctory meeting with President Clinton.

“Take a seat,” President Clinton said to Sosnik, who fell into a yellow-striped sofa across from the young leader. It was February 1995. Just three months earlier, voters had signaled their frustration with President Clinton by abruptly ending the Democratic Party’s forty-year reign over Congress. The president already was considered a lame duck, not that he ever saw it that way.

“I’m really looking forward to the campaign,” President Clinton told Sosnik, jumping excitedly into a conversation about the 1996 presidential race. He said he expected to win reelection, a prediction that caught Sosnik off guard. Suppressing a smile, Sosnik replied, “Me, too.” The new White House political director walked from the Oval Office wondering why President Clinton was looking forward to a campaign that few thought he could win.

Sosnik was not the only Clinton adviser worried about the president’s chances. Shortly after Sosnik took the job, the pollster Mark Penn completed a confidential survey for President Clinton that suggested that 65 percent of Americans would not consider voting for the incumbent in 1996. It was not just that these people were saying they didn’t like the president or didn’t approve of his performance. They were determined to never, ever vote for him. Talk about tough political terrain.

The lowest point of Clinton’s presidency was yet to come. It was two months later, on the night of April 18, 1995, when the White House press corps filed into the elegant East Room for a prime-time news conference. Past presidents had made these events must-see TV. John F. Kennedy had kept reporters at bay with sharp humor. Richard Nixon had scowled at questioners over Watergate. Former actor Ronald Reagan had charmed the nation even as he muffed policy details. But in April 1995 there was little interest in a White House news conference.

President Clinton was overshadowed in Washington by the bombastic leader of the GOP revolution, House Speaker Newt Gingrich. The networks had just given Gingrich airtime to address the nation on the hundredth day of the new Congress, a remarkable show of deference for a House speaker. By contrast, just one of the three major networks, CBS, agreed to broadcast President Clinton’s news conference, and its ratings were less than half those of Frasier on NBC and Home Improvement on ABC.

Making matters worse, President Clinton admitted in that April 18 news conference how far he had fallen. A reporter asked whether he worried about “making sure your voice will be heard” if no one was covering his words. President Clinton replied, “The Constitution gives me relevance. The power of our ideas gives me relevance. The record we have built up over the last two years and the things we’re trying to do to implement it give it relevance. The president is relevant here, especially an activist president—and the fact that I’m willing to work with Republicans.” When the president of the United States plaintively argues his relevancy, it’s time to ditch plans for a second term and start working on the presidential library.

“If he would have taken voters on face value, they would never reelect him because so many voters said that they were unalterably opposed to his election,” Penn said a decade later. “We were at low tide.”

The tide began to rise the day after the disastrous April news conference, when domestic terrorists bombed the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City. The bombing was for President Clinton what September 11 would be for President Bush—a national tragedy that cried out for leadership. Both men seized the moment. But, as at the Bush White House, nothing was left to chance by the polit...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Colophon

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Epigraph

- Contents

- Authors’ Note

- Introduction: Stormy Present

- Part I: Great Connectors

- Part II: Great Change

- Acknowledgments

- Appendix 1. What’s Your Tribe?

- Appendix 2. Changes in Technology and American Lifestyle

- A Note on Sources

- Index

- About the Authors

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Applebee's America by Ron Fournier,Douglas B. Sosnik,Matthew J. Dowd in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business Development. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.