On February 10, 2005, North Korea’s state-run Pyongyang Radio informed its captive audience that the president of the United States had developed a plan to engulf the world in a sea of flames and to rule the planet through the forced imposition of freedom. In self-defense, the newsreader continued, North Korea had manufactured nuclear weapons.

That evening, Rick Nieman of the Netherlands’ RTL Television asked U.S. Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice to respond to Pyongyang’s assertion that North Korea needed nuclear weapons to cope with “the Bush administration’s ever more undisguised policy to isolate…the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea.” Rice countered: “This is a state that has been isolated completely for its entire history…. They have been told that if they simply make the decision…to give up their nuclear weapons and nuclear-weapons program, to dismantle them verifiably and irreversibly, there is a completely new path available to them…. So the North Koreans should reassess this and try to end their own isolation.”1

That’s the official U.S. policy on North Korea: If North Korea submits to the complete, verifiable, irreversible dismantlement of its nuclear program, Washington will end North Korea’s isolation and support the integration of Kim Jong-Il’s regime into the international community. If, on the other hand, North Korea persists in developing its nuclear capacity, Washington will “further deepen North Korea’s isolation.”

To many, this policy is grounded in common sense. If North Korea begins to behave as Washington wants, the United States should reward the regime. If it does not, Washington should further seal it off. If Kim will quiet the relentless drumbeat of war and renounce his campaign to build an arsenal of the world’s most destructive weapons, Washington should allow North Korea to escape its wretched isolation. If, on the other hand, North Korea insists on causing trouble, bargains in bad faith, ratchets up tensions in East Asia, violates its agreements, and perhaps even sells the world’s most dangerous weapons to the world’s most dangerous people, the regime must be swiftly and soundly punished. Kim Jong-Il and those who administer his government must be persuaded that his broken promises and misdeeds doom his regime to perpetual quarantine.

If this policy is properly applied, so the thinking goes, the message will be received far beyond North Korea. Common sense demands that Washington demonstrate that America stands ready to achieve its foreign- and security-policy goals with the sweetest carrots and sharpest sticks available. So the thinking goes.

But, as we’ll see in the next chapter, this approach has failed to help Washington achieve its goals in North Korea. In fact, it has produced policies that have had virtually the opposite of their intended effects. Of course, U.S. foreign policies that produce the reverse of their intended consequences are not limited to either North Korea or the George W. Bush administration. Policy failures over many decades in Iraq, Iran, Cuba, Russia, and many other states demonstrate that policymakers need an entirely new geopolitical framework, one that captures the way decision-makers within these states calculate their interests and make their choices—and one that offers insight into how more effective U.S. policies can be formulated.

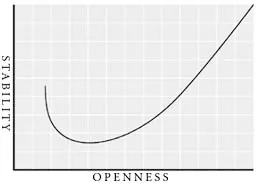

There is a counterintuitive relationship between a nation’s stability and its openness, both to the influences of the outside world and within its borders. Certain states—North Korea, Burma, Belarus, Zimbabwe—are stable precisely because they are closed. The slightest influence on their citizens from the outside could push the most rigid of these states toward dangerous instability. If half the people of North Korea saw twenty minutes of CNN (or of Al Jazeera for that matter), they would realize how egregiously their government lies to them about life beyond the walls. That realization could provoke widespread social upheaval. The slightest improvement in the ability of a country’s citizens to communicate with one another—the introduction of telephones, e-mail, or text-messaging into an authoritarian state—can likewise undermine the state’s monopoly on information.

Other states—the United States, Japan, Sweden—are stable because they are invigorated by the forces of globalization. These states are able to withstand political conflict, because their citizens—and international investors—know that political and social problems within them will be peacefully resolved by institutions that are independent of one another and that the electorate will broadly accept the resolution as legitimate. The institutions, not the personalities, matter in such a state.

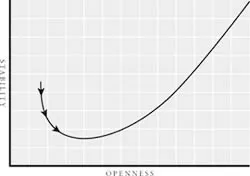

Yet, for a country that is “stable because it’s closed” to become a country that is “stable because it’s open,” it must go through a transitional period of dangerous instability. Some states, like South Africa, survive that journey. Others, like Yugoslavia, collapse. Both will be visited in Chapter Four. It is more important than ever to recognize the dangers implicit in these processes. In a world of lightning-fast capital flight, social unrest, weapons of mass destruction, and transnational terrorism, these transformations are everybody’s business.2

The J curve is a tool designed to help policymakers develop more insightful and effective foreign policies. It’s meant to help investors understand the risks they face as they invest abroad. It’s also intended to help anyone curious about international politics better understand how leaders make decisions and the impact of those decisions on the global order. As a model of political risk, the J curve can help us predict how states will respond to political and economic shocks, and where their vulnerabilities lie as globalization erodes the stability of authoritarian states.

J curves aren’t new to models of political and economic behavior. In the 1950s, James Davies developed a quite different curve that expressed the dangers inherent in a gap between a people’s rising economic expectations and their actual circumstances. Another J curve measured the relationship between a state’s trade deficit and the value of its currency. The purpose of the J curve in this book is quite different and much broader. It is intended to describe the political and economic forces that revitalize some states and push others toward collapse.

The J Curve: Nations to the left of the dip in the J curve are less open; nations to the right are more open. Nations higher on the graph are more stable; those that are lower are less stable.

What is the J curve? Imagine a graph on which the vertical axis measures stability and the horizontal axis measures political and economic openness to the outside world. (See figure above.) Each nation whose level of stability and openness we want to measure appears as a data point on the graph. These data points, taken together, produce a J shape. Nations to the left of the dip in the J are less open; nations to the right are more open. Nations higher on the graph are more stable; those that are lower are less stable.

In general, the stability of countries on the left side of the J curve depends on individual leaders—Stalin, Mao, Idi Amin. The stability of states on the right side of the curve depends on institutions—parliaments independent of the executive, judiciaries independent of both, nongovernmental organizations, labor unions, citizens’ groups. Movement from left to right along the J curve demonstrates that a country that is stable because it is closed must go through a period of dangerous instability as it opens to the outside world. (See figure.) There are no shortcuts, because authoritarian elites cannot be quickly replaced with institutions whose legitimacy is widely accepted.

Movement Along the J Curve: Movement from left to right along the J curve demonstrates that a country that is stable because it is closed must go through a period of dangerous instability as it opens to the outside world.

“Openness” is a measure of the extent to which a nation is in harmony with the crosscurrents of globalization—the processes by which people, ideas, information, goods, and services cross international borders at unprecedented speed. How many books written in a foreign language are translated into the local language? What percentage of a nation’s citizens have access to media outlets whose signals originate from beyond their borders? How many are able to make an international phone call? How much direct contact do local people have with foreigners? How free are a nation’s citizens to travel abroad? How much foreign direct investment is there in the country? How much local money is invested outside the country? How much cross-border trade exists? There are many more such questions.

But openness also refers to the flow of information and ideas within a country’s borders. Are citizens free to communicate with one another? Do they have access to information about events in other regions of the country? Are freedoms of speech and assembly legally established? How transparent are the processes of local and national government? Are there free flows of trade across regions within the state? Do citizens have access to, and influence in, the processes of governance?

“Stability” has two crucial components: the state’s capacity to withstand shocks and its ability to avoid producing them. A nation is only unstable if both are absent. Saudi Arabia remains stable because, while it has produced numerous shocks over the last decade, it remains capable of riding out the tremors. The House of Saud is likely to continue to absorb political shocks without buckling for at least the next several years. Kazakhstan is stable for the opposite reason. Its capacity to withstand a major political earthquake is questionable but, over the course of its fifteen-year history as a sovereign state, it hasn’t created its own political crises. How Kazakhstan might withstand a near-term political shock, should one occur, is far more open to question than in Saudi Arabia, where the real stability challenges are much longer-term.

To illustrate how countries with varying levels of stability react to a similar shock, consider the following: An election is held to choose a head of state. A winner is announced under circumstances challenged by a large number of voters. The nation’s highest judicial body generates controversy as it rules on a ballot recount. That happened in Taiwan in 2003 and Ukraine in 2004. Demonstrations closed city streets, the threat of civil violence loomed, local economies suffered, and international observers speculated on the continued viability of both governments.* Of course, similar events erupted in the United States in 2000, without any significant implications for the stability of the country or its financial markets.

Stability is the capacity to absorb such shocks. Anyone can feel the difference between a ride in a car with good shock absorbers and in one that has no shock absorbers. Stability fortifies a nation to withstand political, economic, and social turbulence. Stability enables a nation to remain a nation.

Levels of Stability

A highly stable country is reinforced by mature state institutions. Social tensions in such a state are manageable: security concerns exist within expected parameters and produce costs that are predictable. France may suffer a series of public-sector strikes that paralyze the country for several weeks. When these strikes occur, no one fears that France will renounce its commitment to democracy and an open society. Nor do they fear these shocks might generate a challenge from outside the country. No one worries that political battles within France might tempt Germany to invade—as it did three times between 1870 and 1940.

States with moderate stability have economic and political structures that allow them to function reasonably effectively; but there are identifiable challenges to effective governance. When Jiang Zemin passed leadership of the Chinese government, the Communist Party, and the People’s Liberation Army to Hu Jintao, very few inside China publicly questioned the move’s legitimacy. If any had—if Chinese workers had taken to the streets as French workers so often do—the state would have moved quickly to contain the demonstrations. Whether China’s rigid, political structure can indefinitely survive the intensifying social dislocations provoked by its explosive economic growth is another matter.

Low-stability states still function—they are able to enforce existing laws and their authority is generally recognized. But they struggle to effectively implement policies or to otherwise change the country’s political direction. These states are not well prepared to cope with sudden shocks. As an oil-exporting nation, Nigeria benefits from high energy prices. But its central government is unable to enforce the law in the Niger Delta region, where most of Nigeria’s oil is located. A group called the Niger Delta People’s Volunteer Force has repeatedly threatened “all-out war” against the central government unless it grants the region “self-determination.” The rebels briefly shut down 40 percent of Nigeria’s oil production in 2003 and forced President Olusegun Obasanjo to negotiate with them. The problem flared again in 2005 and 2006.

A state with no stability is a failed state; it can neither implement nor enforce government policy. Such a country can fragment, it can be taken over by outside forces, or it can descend into chaos. Somalia fell apart in 1991, when several tribal militias joined forces to unseat the country’s dictator, and then turned on each other. Since then, warlords have ruled most of the country’s territory. Their rivalries have probably killed half a million and made refugees of another 750,000. More than a dozen attempts to restore order, mostly backed by Western benefactors, have failed. Any Somali leader who intends to restore Mogadishu’s authority over all of Somalia’s territory will have to disarm tens of thousands of gunmen, stop the steady stream of arms trafficking, set up a working justice system, and revitalize a stricken economy. Meanwhile, there are warlords, extremists, smugglers, and probably terrorists with a clear interest in scuttling the process. And while political conflicts in France don’t encourage Germany to invade, there are clear threats to any future stability in Somalia from just across the border. One of the few African nations offering to send peacekeeping troops to help Somalia reestablish civil order is Ethiopia, a neighbor with a long history of troublemaking there. The arrival of any foreign troops, especially Ethiopians, could reignite Somalia’s civil war.

In August 2005, South Africa went public with concerns that its neighbor Zimbabwe stood on the brink of becoming just such a failed state. Representatives of South Africa’s government said a sizable loan designed to rescue Robert Mugabe’s country from default on International Monetary Fund obligations might be conditioned on Mugabe’s willingness to include the opposition in a new government of national unity. South Africa has good reason for concern. When state failure strikes your neighbor, the resulting chaos can undermine your stability as well, as refugees, armed conflict, and disease spill across borders.

Democracy and Stability

Democracy is not the only—or even the most important—factor determining a nation’s stability. To illustrate the point, consider again the U.S. presidential election of 2000. Did America sail through the political storm with little real damage to its political institutions simply because the United States is a democracy? Taiwan is a democracy too, albeit a less mature one, but its citizens felt the jolt of every pothole on the ride through its electoral crisis. In Turkmenistan—not a democracy by any definition—the open rigging of presidential elections produces hardly a ripple, nothing like the unrest produced in Taiwan. Much of Turkmenistan’s stability is based on the extent to which its authoritarianism is taken for granted; a rigged election is not the exception. Democratic or not, countries in which stability is in question are more susceptible to sudden crises, more likely to unleash their own conflicts, and more vulnerable to the worst effects of political shock. Yet, for the short term, authoritarian Turkmenistan must be considered more stable than democratic Taiwan.

At first glance, the J curve seems to imply that democracies are the opposite of authoritarian states. The reality is more complicated. In terms of stability—the vertical axis on the J curve—police states have more in common with democracies than they do with badly run authoritarian regimes. In other words, in terms of stability, Algeria has more in common with the United States than it does with Afghanistan. Consolidated democratic regimes—Germany, Norway, and the United States—are the most stable of states. They can withstand terrible shocks without a threat to the integrity of the state itself. Poorly functioning states—Somalia, Moldova, or Haiti—are the least likely to hold together. But consolidated authoritarian regimes—Cuba, Uzbekistan, and Burma—often have real staying power.

The Elements of Stability

A nation’s stability is composed of many elements, and while one of these elements may be reinforcing the state’s overall stability, another may be undermining it. On the one hand, Turkey’s possible entry into the European Union enhances the nation’s political and social stability. So long as Ankara remains on track for EU accession, Turkey’s government has incentive to implement the reforms the Europeans require—reforms that strengthen the independ...