- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

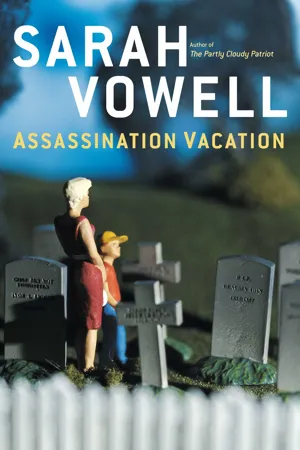

Assassination Vacation

About this book

New York Times bestselling author of The Wordy Shipmates and contributor to NPR’s This American Life Sarah Vowell embarks on a road trip to sites of political violence, from Washington DC to Alaska, to better understand our nation’s ever-evolving political system and history.

Sarah Vowell exposes the glorious conundrums of American history and culture with wit, probity, and an irreverent sense of humor. With Assassination Vacation, she takes us on a road trip like no other—a journey to the pit stops of American political murder and through the myriad ways they have been used for fun and profit, for political and cultural advantage.

From Buffalo to Alaska, Washington to the Dry Tortugas, Vowell visits locations immortalized and influenced by the spilling of politically important blood, reporting as she goes with her trademark blend of wisecracking humor, remarkable honesty, and thought-provoking criticism. We learn about the jinx that was Robert Todd Lincoln (present at the assassinations of Presidents Lincoln, Garfield, and McKinley) and witness the politicking that went into the making of the Lincoln Memorial. The resulting narrative is much more than an entertaining and informative travelogue—it is the disturbing and fascinating story of how American death has been manipulated by popular culture, including literature, architecture, sculpture, and—the author’s favorite—historical tourism. Though the themes of loss and violence are explored and we make detours to see how the Republican Party became the Republican Party, there are all kinds of lighter diversions along the way into the lives of the three presidents and their assassins, including mummies, show tunes, mean-spirited totem poles, and a nineteenth-century biblical sex cult.

Sarah Vowell exposes the glorious conundrums of American history and culture with wit, probity, and an irreverent sense of humor. With Assassination Vacation, she takes us on a road trip like no other—a journey to the pit stops of American political murder and through the myriad ways they have been used for fun and profit, for political and cultural advantage.

From Buffalo to Alaska, Washington to the Dry Tortugas, Vowell visits locations immortalized and influenced by the spilling of politically important blood, reporting as she goes with her trademark blend of wisecracking humor, remarkable honesty, and thought-provoking criticism. We learn about the jinx that was Robert Todd Lincoln (present at the assassinations of Presidents Lincoln, Garfield, and McKinley) and witness the politicking that went into the making of the Lincoln Memorial. The resulting narrative is much more than an entertaining and informative travelogue—it is the disturbing and fascinating story of how American death has been manipulated by popular culture, including literature, architecture, sculpture, and—the author’s favorite—historical tourism. Though the themes of loss and violence are explored and we make detours to see how the Republican Party became the Republican Party, there are all kinds of lighter diversions along the way into the lives of the three presidents and their assassins, including mummies, show tunes, mean-spirited totem poles, and a nineteenth-century biblical sex cult.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER ONE

The bullet that killed Lincoln (based on an undated allegorical lithograph in the collection of the Library of Congress, in which John Wilkes Booth is entombed inside his own ammo). The actual bullet that killed Lincoln is considerably more smushed and on display in the National Museum of Health and Medicine in Washington, D.C., next to bone fragments from the president’s skull.

Going to Ford’s Theatre to watch the play is like going to Hooters for the food. So I had intended to spend the first act of 1776, a musical about the Declaration of Independence, ignoring the stage and staring at Abraham Lincoln’s box from my balcony seat. Then I was going to leave at intermission. Who wants to hear the founding fathers break into song? Me, it turns out. Between eloquent debates about the rights of man, these wiseacres in wigs traded surprisingly entertaining trash talk in which a deified future president like Thomas Jefferson is deplored as a “red-headed tombstone.” George Washington’s amusingly miserable letters from the front—New Jersey is full of whores giving his soldiers “the French disease”—are read aloud among the signers with eye-rolling contempt, followed by comments such as “That man would depress a hyena.” Plus, Benjamin Franklin was played by the actor who played the Big Lebowski in The Big Lebowski. I was so sucked into 1776 that whole production numbers like “But, Mr. Adams” could go by and I wouldn’t glance Lincolnward once, wrapped up in noticing that that second president could really sing.

Deciding to stay for act II, I spend intermission in the Lincoln Museum administered by the National Park Service in the theater’s basement. There are the forlorn blood spots on the pillow thought to have cradled the dying Lincoln’s head; the Lincoln mannequin wearing the clothes he was shot in; the key to the cell of conspirator Mary Surratt; the gloves worn by Major Henry Rathbone, who accompanied the Lincolns to the theater and was stabbed by Booth in the president’s box; Booth’s small, pretty derringer; and, because it’s some kind of law for Lincoln-related sites to have them, sculptor Leonard Volk’s cast of Lincoln’s hands.

Intermission over, I found myself looking forward to the rest of the play, happily bounding back up to my seat. But I paused on the balcony stairs for a second, thinking about how these were the very stairs that Booth climbed to shoot at Lincoln and how sick is this? Then I remembered, oh no they’re not. The interior of the Ford’s Theatre in which Lincoln was shot collapsed in 1893, but then, in 1968, the National Park Service dedicated this restoration, duplicating the setting of one of the most repugnant moments in American history just so morbid looky-loos like me could sign up for April 14, 1865, as if it were some kind of assassination fantasy camp. So how sick is that?

Act II of 1776 isn’t as funny as act I, and not just because Ben Franklin gets to crack fewer sex jokes. It’s time for the slavery question. Jefferson and Adams want a document about liberty and equality to include a tangent denouncing kidnapping human beings and cramming them into floating jails only to be auctioned off and treated as animals. This is followed by the expected yelling of southerners who refuse to sign such hogwash, pointing out that slavery is in the Bible, their way of life, blah, blah. What’s unexpected is the song. Edward Rutledge of South Carolina (his brother would go on to sign the Constitution) sings a strange but effective j’accuse called “Molasses to Rum,” in which he implicates New England ships and merchants in the slave trade triangle, asking John Adams: Boston or Charleston, “Who stinketh most?”

This script as performed by these actors really does give the audience a feel for the anguish, embarrassment, and disappointment Adams and Jefferson went through yielding to the southerners’ edit. “Posterity will never forgive us,” Adams sighs, caving in.

Even though the scene couldn’t be more gripping, my head snaps up away from the action to stare at Lincoln’s box. The thing that makes seeing this play in Ford’s Theatre more meaningful than anywhere else is that I can look from the stage to Lincoln’s box and back again, and I can see exactly where this compromise in 1776 is pointing: into the back of Lincoln’s head in 1865.

“This country was formed for the white, not for the black man,” John Wilkes Booth reportedly wrote on the day he pulled the trigger. (I say reportedly because the letter, to the editors of a Washington newspaper, was destroyed in 1865 but later “reconstructed” and reprinted in 1881.) Booth (again, reportedly, but it sounds like him) continued, “And, looking upon African slavery from the same standpoint as the noble framers of our constitution, I, for one, have ever considered it one of the greatest blessings, both for themselves and us, that God ever bestowed upon a favored nation.” So this is whom we’re dealing with—not the raving madman of assassination lore, but a calculating, philosophical racist. Then again, anyone who has convinced himself that slavery is a “blessing” for the slaves is a little cracked.

After the play I take a walk to the Lincoln Memorial. It’s late. Downtown D.C. is vacant this time of night. Like that of the Lincoln administration, this is a time of war. Back then, Union soldiers camped out on the Mall. Nowadays, ever since the attack on the Pentagon in 2001, the capital has been clamped down. How is this manifested? Giant planters blocking government buildings, giant planters barricading every other street. Theoretically, the concrete flowerpots are solid enough to fend off a truck bomb. And yet the effect is ridiculous, as if we believe we can protect ourselves from suicide bombers by hiding behind blooming pots of marigolds, flowers whose main defensive property is repelling rabbits.

I walk down the darkened Mall past the white protruding phallus that is the Washington Monument. It looks goofy enough in the light of day but ugliest at night, when the red lights at its tippy top blink so as to keep airplanes from crashing into it, a good idea I know, but still, those beady blinking eyes make it come across as fake and sad, the way robots used to look in old movies before George Lucas came along.

I’m alone out here. Even though the Mall is a pretty safe place, I’ve read way too many pulpy coroner novels with first sentences such as “I spent a long afternoon at the morgue,” so I’m feeling a little mugable. Nervously, I shove my hands in my pockets. In the forensics novels the contents of a victim’s pockets on the night of her death Say Something about her character. My Ford’s Theatre ticket stub and Jimmy Carter key chain say that I am the corniest, goody-goody person in town. Luckily, I survived the evening unscathed so no one will ever find out about that losery Jimmy Carter key chain.

The Library of Congress has a whole display case of items in Lincoln’s pockets when he died. His pocketknife, two pairs of spectacles, and a Confederate five-dollar bill are spread out on red velvet. They would probably display the lint too if someone had had the foresight to keep it. The items take on a strange significance. Those are the glasses he must have worn to read his beloved Shakespeare. He could have used the pocketknife to carve the apple he liked to eat for lunch.

The contents of John Wilkes Booth’s pockets also get the glass case treatment. At Ford’s Theatre, I looked at the five photographs of women in the womanizing Booth’s pockets when he died, and I couldn’t help but believe that I picked up new insight into his character, that he wasn’t just a presidential killer, he was a lady-killer too. Four of the women were actresses he knew. The fifth picture captures Booth’s secret fiancée, Lucy Hale, in profile. Lucy was spotted with Booth the morning of the assassination, probably around the same time her ex-senator father John P. Hale, Lincoln’s newly appointed ambassador to Spain, was meeting with the president in the White House. Hale, a New Hampshire Republican, was the first abolitionist ever elected to the U.S. Senate. One reason he was so keen on absconding to Europe on a diplomatic appointment was to put an ocean between his pretty daughter and Booth, whom the senator knew to be a pro-slavery southern sympathizer and, worse, an actor. In fact, Hale would have preferred to marry Lucy off to another young man he had noticed admiring her—the president’s twenty-one-year-old son, Robert Todd Lincoln.

The Lincoln Memorial is at its loveliest when the sun goes down. It glows. It’s quiet. There are fewer people and the people who are here at this late hour are reverent and subdued, but happy. The lights bounce off the marble and onto their faces so that they glow too, their cheeks burned orange as if they’ve had a sip of that good bourbon with the pretty label brewed near the Kentucky creek where Lincoln was born.

I read the two Lincoln speeches that are chiseled in the wall in chronological order, Gettysburg first. Shuffling past the Lincoln statue, I pause under the white marble feet, swaying back and forth a little so it looks like his knees move. A moment of whimsy actually opens me up for the Second Inaugural, a speech that is all the things they say—prophetic, biblical, merciful, tough. The most famous phrase is the most presidential: with malice toward none. I revere those words. Reading them is a heartbreaker considering that a few weeks after Lincoln said them at the Capitol he was killed. But in my two favorite parts of the speech, Lincoln is sarcastic. He’s a writer. And in his sarcasm and his writing, he is who he was. He starts off the speech reminding his audience of the circumstances of his First Inaugural at the eve of war. It’s a (for him) long list, remarkably even-handed and restrained, pointing out that both the North and the South were praying to the same god, as if they were just a couple of football teams squaring off in the Super Bowl. Then things turn mischievous: “It may seem strange that any men should dare to ask a just God’s assistance in wringing their bread from the sweat of other men’s faces; but let us judge not that we be not judged.” Know what that is? A zinger—a subtle, high-minded, morally superior zinger. I glance back at the Lincoln statue to see if his eyes have rolled. Then, at the end of this sneaky list of the way things were, he simply says, “And the war came.” Kills me every time. Four little words to signify four long years. To call this an understatement is an understatement. To read this speech is to see how Lincoln’s mind worked, to see how he governed, how he lived. There’s the narrative buildup, the explanation, the lists of pros and cons; he came late to abolitionism, sought compromise, hoped to save the Union without war, etc., until all of a sudden the jig is up. The man who came up with that teensy but vast sentence, And the war came, a four-word sentence that summarizes how a couple of centuries of tiptoeing around evil finally stomped into war, a war he says is going to go on “until every drop of blood drawn with the lash, shall be paid by another drawn with the sword,” is the same chief executive who in 1863 signed the Emancipation Proclamation. I’ve seen that paper. It’s a couple of pages long. But after watching the slavery agony in 1776, I like to think of it as a postcard to Jefferson and Adams, another four-word sentence: Wish you were here.

When I used to get to the end of the Second Inaugural, in which Lincoln calls on himself and his countrymen “to do all which may achieve and cherish a just, and a lasting peace,” I always wondered how anyone who heard those words could kill the person who wrote them. Because that day at the Capitol, Booth was there, attending the celebration as Lucy Hale’s plus-one. In the famous Alexander Gardner photograph of Lincoln delivering the speech, you can spot Booth right above him, lurking. And what was Booth’s reaction to hearing Lincoln’s hopes for “binding up the nation’s wounds”? Booth allegedly told a friend, “What an excellent chance I had to kill the president, if I had wished, on Inauguration Day!”

I used to march down the memorial’s steps mourning the loss of the second term Lincoln would never serve. But I don’t think that way anymore. Ever since I had to build those extra shelves in my apartment to accommodate all the books about presidential death—I like to call that corner of the hallway “the assassination nook”—I’m amazed Lincoln got to live as long as he did. In fact, I’m walking back to my room in the Willard Hotel, the same hotel where Lincoln had to sneak in through the ladies’ entrance before his first inauguration because the Pinkerton detectives uncovered a plot to do him in in Baltimore before he even got off the train from Springfield. All through his presidency, according to his secretary John Hay, Lincoln kept a desk drawer full of death threats. Once, on horseback between the White House and his summer cottage on the outskirts of town, a bullet whizzed right by his head. So tonight, I leave the memorial knowing that the fact that Lincoln got to serve his whole first term is a kind of miracle.

Mary Surratt’s D.C. boardinghouse, where John Wilkes Booth gathered his co-conspirators to plot Lincoln’s death, is now a Chinese restaurant called Wok & Roll. I place an order for broccoli and bubble tea, then squint at an historic marker in front of the restaurant quoting Andrew Johnson that this was “the nest in which the egg was hatched.” For her southern hospitality, Mrs. Surratt, who owned this boardinghouse as well as the tavern in Maryland where Booth would proceed after shooting Lincoln, would become the first woman executed by the U.S. government. She was hanged, along with George Atzerodt, David Herold, and Lewis Powell, in 1865. Here in her former boardinghouse sat Booth, Atzerodt, Herold, and Powell, along with Samuel Arnold, Michael O’Laughlin, and Mary’s weasel son John, who would hightail it to Europe after the assassination, leaving his mom to get strung up in his stead.

The plot to murder Abraham Lincoln started out as a plot to kidnap him, or rather it was one of several such kidnapping schemes. In their landmark study Come Retribution, William A. Tidwell, James O. Hall, and David Winfred Gaddy make a convincing case that John Wilkes Booth was a member of the Confederate Secret Service throughout the Civil War. Booth claimed to have been running messages and medicine across the lines for years, often traveling to and from Canada to confer with Confederate spooks up there. Booth was able to do this, to move freely between North and South, because he was a nationally famous actor, just as movie stars today get whisked through airport security while the rest of us stand in long lines taking off our shoes. The Confederates were shrewd to take advantage of Booth’s fame. There is a lesson here for the terrorists of the world: if they really want to get ahead, they should put less energy into training illiterate ten-year-olds how to fire Kalashnikovs and start recruiting celebrities like George Clooney. I bet nobody’s inspected that man’s luggage since the second season of ER.

Tidwell, Hall, and Gaddy also persuasively and intriguingly argue that the plan to kidnap Lincoln had its origins as a retaliatory measure after it was discovered that Lincoln had authorized the capture of Jefferson Davis. Also, knowing how the Confederate ranks were thinning, General Grant had put a stop to prisoner of war exchanges. The South needed their dwindling stock of soldiers back more than the North. And so the notion of kidnapping President Lincoln and exchanging him for southern POWs seemed logical and appealing, though by most accounts Davis himself seemed most aware of the consequences—that odds are, kidnapping the president of the United States is going to get said president killed. Even Davis thought himself above such dishonorable unpleasantness.

Then, on April 9, 1865, Appomattox. The war was winding down and the POWs would soon go home. Kidnapping Lincoln no longer served much purpose. There’s no real consensus among historians as to when exactly the kidnapping plan turned into an assassination plot. It seems likely that Booth changed his mind first and then egged on his partners in crime. Booth and Powell were there on the White House lawn on April 11—a mere two days after Robert E. Lee surrendered to U. S. Grant—when Lincoln gave his speech on reconstruction. To me, this speech is unsatisfying, proposing to extend the right to vote to “very intelligent” blacks and/or those who fought for the Union—black men it goes without saying. But to Booth this halfhearted suggestion was the revelation of an electoral apocalypse. He told Powell, “That means nigger citizenship. Now, by god, I will put him through. That will be the last speech he will ever make.” It was.

Booth’s plan was to kill the nation’s top three leaders so the federal government would dissolve into chaos. Booth would shoot Lincoln. Georg...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Dedication

- Preface

- Chapter One

- Chapter Two

- Chapter Three

- Chapter Four

- Acknowledgments

- About the Author

- Copyright

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Assassination Vacation by Sarah Vowell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Political Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.