eBook - ePub

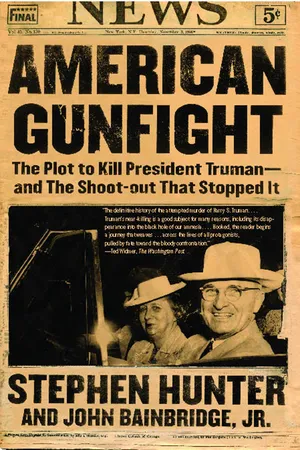

American Gunfight

The Plot to Kill Harry Truman--and the Shoot-out that Stopped It

- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

American Gunfight

The Plot to Kill Harry Truman--and the Shoot-out that Stopped It

About this book

A fast-paced, definitive, and breathtakingly suspenseful account of an extraordinary historical event—the attempted assassination of President Harry Truman in 1950 by two Puerto Rican Nationalists and the bloody shoot-out in the streets of Washington, DC, that saved the president's life.

Written by Pulitzer Prize-winner and New York Times bestselling novelist Stephen Hunter, and John Bainbridge, Jr., an experienced journalist and lawyer, American Gunfight is at once a groundbreaking work of meticulous historical research and the vivid and dramatically told story of an act of terrorism that almost succeeded. They have pieced together, at last, the story of the conspiracy that nearly doomed the president and how a few good men—ordinary guys who were willing to risk their lives in the line of duty—stopped it.

It begins on November 1, 1950, an unseasonably hot afternoon in the sleepy capital. At 2:00 P.M. in his temporary residence at Blair House, the president of the United States takes a nap. At 2:20 P.M., two men approach Blair House from different directions. Oscar Collazo, a respected metal polisher and family man, and Griselio Torresola, an unemployed salesman, don’t look dangerous, not in their new suits and hats, not in their calm, purposeful demeanor, not in their slow, unexcited approach. What the three White House policemen and one Secret Service agent cannot guess is that under each man's coat is a 9mm automatic pistol and in each head, a dream of assassin's glory.

At point-blank range, Collazo and then Torresola draw and fire and move toward the president of the United States.

Hunter and Bainbridge tell the story of that November day with narrative power and careful attention to detail. They are the first to report on the inner workings of this conspiracy; they examine the forces that led the perpetrators to conceive the plot. The authors also tell the story of the men themselves, from their youth and the worlds in which they grew up to the women they loved and who loved them to the moment the gunfire erupted. Their telling commemorates heroism—the quiet commitment to duty that in some moments of crisis sees some people through an ordeal, even at the expense of their lives.

Written by Pulitzer Prize-winner and New York Times bestselling novelist Stephen Hunter, and John Bainbridge, Jr., an experienced journalist and lawyer, American Gunfight is at once a groundbreaking work of meticulous historical research and the vivid and dramatically told story of an act of terrorism that almost succeeded. They have pieced together, at last, the story of the conspiracy that nearly doomed the president and how a few good men—ordinary guys who were willing to risk their lives in the line of duty—stopped it.

It begins on November 1, 1950, an unseasonably hot afternoon in the sleepy capital. At 2:00 P.M. in his temporary residence at Blair House, the president of the United States takes a nap. At 2:20 P.M., two men approach Blair House from different directions. Oscar Collazo, a respected metal polisher and family man, and Griselio Torresola, an unemployed salesman, don’t look dangerous, not in their new suits and hats, not in their calm, purposeful demeanor, not in their slow, unexcited approach. What the three White House policemen and one Secret Service agent cannot guess is that under each man's coat is a 9mm automatic pistol and in each head, a dream of assassin's glory.

At point-blank range, Collazo and then Torresola draw and fire and move toward the president of the United States.

Hunter and Bainbridge tell the story of that November day with narrative power and careful attention to detail. They are the first to report on the inner workings of this conspiracy; they examine the forces that led the perpetrators to conceive the plot. The authors also tell the story of the men themselves, from their youth and the worlds in which they grew up to the women they loved and who loved them to the moment the gunfire erupted. Their telling commemorates heroism—the quiet commitment to duty that in some moments of crisis sees some people through an ordeal, even at the expense of their lives.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access American Gunfight by Stephen Hunter,John Bainbridge in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1. A Drive Around Washington

This story could start in a great number of places. It could start with Columbus’s arrival on a Caribbean island called Borinquen in 1493, or General Nelson A. Miles’s arrival on the same island, now called Puerto Rico, in 1898. It could start at a Harvard graduation, a football game in DuBois, Pennsylvania, the collapse of a staircase railing in the capitol in San Juan, even a Virginia farm boy’s decision to go to the city and become a police officer.

But no matter where it starts, it ends in the same place: a fury of gunfire that broke apart a quiet afternoon on Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington, D.C., just across from the White House, November 1, 1950. It ends as most gunfights do: with men dead, men wounded, wives in mourning, causes lost, lives shattered, duty followed hard, and regrets that never pass.

But let’s begin—arbitrarily, to be sure—at 3:18 P.M., September 23, 1950, in Washington. On that day at that time, a father and a daughter slipped out the back door of their Federal-style townhouse, climbed into a well-waxed specially built black Lincoln driven by a tough-looking customer who carried a gun, and went for a little drive. The old man may have looked like a rich snoot out on the town but “rich snoot” doesn’t describe him: he was famously plainspoken, hardworking, sensible, tough and had the common touch. He was sixty-six, well dressed, a giver-of-hell from the Show-Me State, a man who stood in the kitchen no matter the heat. He was the thirty-third president of the United States, Harry S. Truman.

His daughter, half a head shorter, was an elegant, poised young woman who took more after her mother than the pepperpot ex-haberdasher, ex–artillery officer who was her father. Margaret Truman, twenty-six, was pursuing a career as a concert singer, touring the East Coast; she always had the dignity of a diva. She had taken this weekend off and had returned Friday afternoon by train from New York—Compartment A, Car 250, Train 125, accompanied by Special Agent Theodore Peters—to visit her father while her mother, Bess, was off in the Truman hometown of Independence, Missouri.

The mansion the president departed that afternoon bore the name Blair-Lee House, sited diagonally across Pennsylvania Avenue from the White House. A regal, elegant dwelling from the outside, it served as substitute home for the chief executive family while the 130-odd-year-old living quarters of the White House across the street were being modernized.

The father and daughter were close: he was a devoted and doting dad who a few months later would fire off an angry letter to Washington Post music critic Paul Hume, who had said unkind things about his daughter’s singing. “Some day I hope to meet you. When that happens you’ll need a new nose, a lot of beefsteak for black eyes, and perhaps a supporter below!” the president wrote, giving hell as was his style.

The drive, to nowhere important, lasted a little less than an hour, until 4:12 P.M. The day had clouded over but it was warm—74 degrees at 3:15—and it is not recorded what the two discussed as they traveled. But it can’t have been a happy time.

For even as they moved through the quiet streets of the capital and enjoyed the pleasure of an early fall day, a political drama played out under the big white dome that stood upon the hill that dominated the federal triangle. Possibly the president didn’t look at the Capitol; he suspected he was going to lose this one, and his mood must have been disgust and contempt.

The drama, at that very second dominating the U.S. Senate, swirled about the McCarran Act, an eighty-one-page accumulation of internal security—some would call it “red-scare”—legislation proposed by an old enemy of Truman’s from the Senate, the seventy-four-year-old Democrat from Nevada. Pat McCarran, a man with “a profile that belonged on a Roman coin: a large hawkish nose that seemed to incline lower with age and thick, wavy white hair cresting high on his head,” was a shrewd politician and, unlike the more famous but less effective Joseph McCarthy, he was an insider, “a master of parliamentary procedure.”

His bill was a patchwork of the many different security bills that had been circulating around the Congress in the years after World War II when, in the wake of several security scandals such as those involving Alger Hiss, Klaus Fuchs, and the Rosenbergs, the fear of communist espionage and subversion was at its highest; the act mandated, among other things, that communists and front groups register with the government and declare their literature as propaganda, that communists not hold passports or governmental jobs, and that it was now a crime to commit “any act that might contribute to the establishment of a totalitarian dictatorship in the United States,” whatever that might be.

When he introduced it on September 5, McCarran had all but declared war on his opponents: “I serve notice here and now that I will not be a party to any crippling or weakening amendments and that I shall oppose with all the power at my command any move to palm off on the American people any window-dressing substitute measure in the place of sound internal security legislation.”

Truman wasn’t an anti-anti-communist—in 1946, he crafted a temporary loyalty security program for the federal government and made it permanent in 1947—and he was aware that his administration had a reputation for being “soft on communism.” But this was too much. Like many, he believed the bill was a modern-day version of the Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798 and he had “a bedrock belief that the Bill of Rights was the most important part of the Constitution.”

It was a classic Washington mano a mano: two strong-willed men at opposite ends of the Mall locked in bitter opposition over a principle of governance, each willing to fight to the end to win the day, no matter the cost.

Thus, when the bill was passed by both House and Senate after much shrewd maneuvering by McCarran and despite dire warnings from many on Truman’s own staff and even his vice president, Alben Barkley, who knew which way the wind blew, Harry Truman chose to stand against the wind: he vetoed it.

The veto was immediately overturned in the House, and now this very day, this very hour, the Senate argued the issue. The president had made his position clear to that body the day before in a message read by the clerk: “I am taking this action only after the most serious study and reflection and after consultation with the security and intelligence agencies of the government…. We would betray our finest traditions if we attempted, as this bill would attempt, to curb the simple expression of opinion. This we should never do, no matter how distasteful the opinion may be to the vast majority of our people.”

Now only a few argued for the veto, but they held the floor, primarily on the efforts of Senator Bill Langer, a Republican from North Dakota, who had well-known libertarian tendencies; Langer had embarked on a kind of one-man filibuster. In the Senate it was Langer against the world, and everybody knew who would win.

As he drove about the town with his beloved daughter next to him, Harry Truman knew that there was nothing left to do but wait.

The president had another, more dangerous, adversary that day than the senator from Nevada. Where a Pat McCarran came at him with brilliant parliamentary moves, with subtleties of agenda, with fakes and jukes and feints, the angry Puerto Rican Nationalist Pedro Albizu Campos would come more directly—he would send men with guns.

Albizu Campos, sometimes called “El Maestro” or “The Maximum Leader” or by his intimates “The Old Man,” was smallish, olive-skinned, and electric with an almost religious fervor to his beliefs. Harvard-educated and by most standards brilliant, and committed to the ideal of an independent Puerto Rico, the fifty-seven-year-old was a riveting speaker, a shrewd plotter, and commanded the allegiance of a small army of armed, black-shirted soldiers. On this same day, September 23, 1950, he gave a fiery speech that revealed his intentions, not that they had ever been secret and even if they flouted an infamous act called Law 53, which outlawed the expression of such sentiments in Puerto Rico. His words make an interesting counterpoint to Truman’s veto message to the Senate and reveal the essence of this other 1950 mano a mano between two strong men, with not the Mall but an ocean and a culture and a history between them.

At 3:00 P.M.—Harry Truman, lunch and his last official appointment behind him, was getting ready to leave Blair House with Margaret—Albizu appeared at the Gonzáles Theater of Lares, a mountain town a few hours to the south of San Juan, before an audience of three hundred. The speech he delivered was recorded, and broadcast that same evening over radio station WCMN of Arecibo.

It was the climax of a busy day for the Old Man, as his watchers from the Insular Police Internal Security section carefully noted.

They had observed him all day, as they did every day, and they recorded everything.

For example, they recorded that at 7:00 A.M. Albizu left the home of Oscar Colón Delgado in Barrio Pueblo of Hatillo for Lares, “to participate in the NPPR [Nationalist Party of Puerto Rico] celebration ‘Grito de Lares’ which refers to a day in 1868 when a group of Puerto Rican Nationalists succeeded in temporarily overpowering the Spanish garrison at Lares.”

Discreetly, they followed him, to note that he arrived by eight and joined a group of Nationalists in the town plaza. At the head of the group were four officers and thirty-seven members of the NPPR Cadet Corps, in black shirts and white trousers, who quickly gathered into formation. The paramilitary unit led the way to the church. Then at 9:30 the marchers moved on a narrow road, up a hill, to the Lares Cemetery, where they placed flowers on the graves of the martyrs who fell in the revolution of Lares. Then they moved to the plaza and placed another floral offering at the base of an obelisk raised in memory of “the heroes of 1868.”

At three he appeared at the theater. One must imagine the scene: the ornate venue in the center of the picturesque mountain town, the three hundred sweating Nationalists packed into it, the temperature high and humid—it was 89 degrees in Lares that day, building toward a rain that would fall at four—and at the center of this, the small, messianic figure on the stage. He had piercing eyes that seemed to see into people and disarm them immediately. He nearly always dressed the same, almost priest-like in his severity: a black jacket shrouding his narrow shoulders, over a white shirt, and set off by a black bow tie. But when he spoke he became more: he was a fiery, spellbinding orator who knew how to draw a crowd to him and then bring them along, either to lay siege or to share a romantic and imaginary journey to an independent Puerto Rico where the modernity of the Anglo world would be irrelevant to the ideal life of the worker on the land.

It was a long and dense speech—he allowed himself many of the rhetorical indulgences of the great orator, fully aware that his personal magnetism would carry the crowd over the duration of his performance—that cited history and religion, culture and tradition. And it did not shy from the boldly direct.

“It is not easy to give a speech,” he began, “when we have our mother lying in bed and an assassin waiting to take her life. Such is the present situation of our country, of our Puerto Rico: the assassin is the power of the United States of North America. One cannot give a speech while the newborn of our country are dying of hunger, while the adolescents of our homeland are being poisoned with the worst virus, slavery.”

He argued that a state of conflict existed between his country and its oppressors and he cited the philosophic underpinnings of it, the illegality of the United States’s rule over Puerto Rico, its very presence an act of war: “And here the yanquis have been at war fifty-two years against the Puerto Rican nation, and have never acquired the right of anything in Puerto Rico, nor is there any legal government in Puerto Rico, and this is incontestable.”

He railed against the presence of American troops on his island: “Well, are the armed forces here to defend Puerto Ricans? [No,] TO KILL PUERTO RICANS!! That’s the only government here, the rest are scoundrels, and all that crowd of bootlickers [who] say that this is a democracy, the yanquis laugh at them.”

He evoked the standard themes of anti-imperialism: the waste of Puerto Rican manhood in the Korean War, the possibility that germ warfare had been tested on Puerto Ricans, the unfairness of a system that made it necessary for Puerto Ricans to go to the United States to earn a living wage after American capital had wrecked the agricultural economy.

It went on and on, for over two hours, through the rainstorm that came at four, through its cessation, through the coming of cooler weather, the fall of night, on and on.

He finally got to the immediate political issue, which was the upcoming voter registration days—women on November 4, men on November 5—for a later referendum on whether to draw up a new territorial constitution. He opposed the registration, not because he detested constitutions but because he detested the U.S. influence that such an enterprise would necessarily entail. Then—spent, one guesses, exhausted by the passion—he concluded with a promise of things to come and that golden dream of ripping freedom from the bosom of the oppressor.

“All this has to be defied, only as the men of Lares defied despotism—WITH THE REVOLUTION.”

Senator Bill Langer fought on. Asked to surrender the floor, he said furiously, “I said I would not yield.” Like Mr. Smith in Frank Capra’s fabled movie, he alone would stem the tide.

But if his spirit was unbowed, the same cannot be said of his body. At that point, he “stopped speaking, swayed slightly and crashed to the floor.”

He had passed out, and would be removed by ambulance crew to Bethesda Naval Hospital.

The inevitable end came swiftly enough. A few parliamentary maneuvers mounted by the liberals were quickly defeated, and another speaker, Paul Douglas, the progressive Democrat from Illinois, took the floor but eventually relinquished it. Finally, almost twenty-four hours after Truman’s veto message had been read, it was time to vote.

At 4:30 a roll call was taken.

The veto was overturned, 57 to 10.

The McCarran Act became law.

“One of the most distressing political defeats my father ever suffered,” Margaret Truman later wrote.

But Truman got on with his life and the next day saw his daughter off on the train to New York. He wrote his cousin, Ethel Noland, that evening discussing the trying weekend, but only in personal terms, chatting about “Margie” and how she moaned when she found out that her maid had forgotten to pack two fur coats she meant to take with her to New York and how he chided her about not doing things for herself and “I didn’t sympathize with her at all and that made her mader [sic] than ever.”

But then he had an o...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Colophon

- Also by Stephen Hunter

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Authors’ Note

- Introduction

- 1. A Drive Around Washington

- 2. Griselio Agonistes

- 3. Revolution

- 4. The Odd Couple

- 5. Mr. Gonzales and Mr. De Silva Go to Washington

- 6. Early Morning

- 7. Baby Starches the Shirts

- 8. Toad

- 9. The New Guy

- 10. The Buick Guy

- 11. The Guns

- 12. The Ceremony

- 13. Indian Summer

- 14. The Big Walk

- 15. Oscar

- 16. “It Did Not Go Off”

- 17. Pappy

- 18. The Next Ten Seconds

- 19. Resurrection Man

- 20. So Loud, So Fast

- 21. Upstairs at Blair

- 22. Downstairs at Blair

- 23. Borinquen

- 24. Oscar Alone

- 25. The End’s Run

- 26. Good Hands

- 27. The Colossus Rhoads

- 28. Oscar Goes Down

- 29. The Second Assault

- 30. Pimienta

- 31. Point-Blank

- 32. The Man Who Loved Guns

- 33. The Dark Visitors

- 34. Mortal Danger

- 35. The Neighbor

- 36. American Gunfight

- 37. The Good Samaritan

- 38. The Policemen’s Wives

- 39. The Scene

- 40. Inside the Soccer Shoe

- 41. Who Shot Oscar?

- 42. The Roundup

- 43. Taps

- 44. Oscar on Trial

- 45. Deep Conspiracy

- 46. Cressie Does Her Duty

- 47. Oscar Speaks

- 48. - - R - I - -

- Epilogue: Destinies

- Source Notes

- Bibliography

- Acknowledgments

- Index