- 784 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

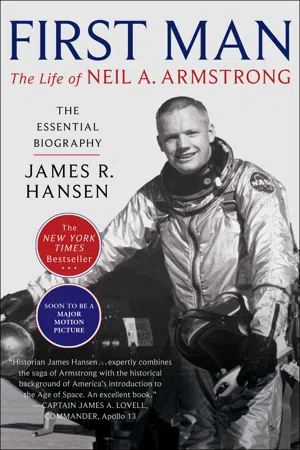

Now a major motion picture, this is the first—and only—definitive authorized account of Neil Armstrong, the man whose “one small step” changed history.

When Apollo 11 touched down on the Moon’s surface in 1969, the first man on the Moon became a legend. In First Man, author James R. Hansen explores the life of Neil Armstrong. Based on over fifty hours of interviews with the intensely private Armstrong, who also gave Hansen exclusive access to private documents and family sources, this “magnificent panorama of the second half of the American twentieth century” (Publishers Weekly, starred review) is an unparalleled biography of an American icon.

In this “compelling and nuanced portrait” (Chicago Tribune) filled with revelations, Hansen vividly recreates Armstrong’s career in flying, from his seventy-eight combat missions as a naval aviator flying over North Korea to his formative trans-atmospheric flights in the rocket-powered X-15 to his piloting Gemini VIII to the first-ever docking in space. For a pilot who cared more about flying to the Moon than he did about walking on it, Hansen asserts, Armstrong’s storied vocation exacted a dear personal toll, paid in kind by his wife and children. For the near-fifty years since the Moon landing, rumors have swirled around Armstrong concerning his dreams of space travel, his religious beliefs, and his private life.

A penetrating exploration of American hero worship, Hansen addresses the complex legacy of the First Man, as an astronaut and as an individual. “First Man burrows deep into Armstrong’s past and present…What emerges is an earnest and brave man” (Houston Chronicle) who will forever be known as history’s most famous space traveler.

When Apollo 11 touched down on the Moon’s surface in 1969, the first man on the Moon became a legend. In First Man, author James R. Hansen explores the life of Neil Armstrong. Based on over fifty hours of interviews with the intensely private Armstrong, who also gave Hansen exclusive access to private documents and family sources, this “magnificent panorama of the second half of the American twentieth century” (Publishers Weekly, starred review) is an unparalleled biography of an American icon.

In this “compelling and nuanced portrait” (Chicago Tribune) filled with revelations, Hansen vividly recreates Armstrong’s career in flying, from his seventy-eight combat missions as a naval aviator flying over North Korea to his formative trans-atmospheric flights in the rocket-powered X-15 to his piloting Gemini VIII to the first-ever docking in space. For a pilot who cared more about flying to the Moon than he did about walking on it, Hansen asserts, Armstrong’s storied vocation exacted a dear personal toll, paid in kind by his wife and children. For the near-fifty years since the Moon landing, rumors have swirled around Armstrong concerning his dreams of space travel, his religious beliefs, and his private life.

A penetrating exploration of American hero worship, Hansen addresses the complex legacy of the First Man, as an astronaut and as an individual. “First Man burrows deep into Armstrong’s past and present…What emerges is an earnest and brave man” (Houston Chronicle) who will forever be known as history’s most famous space traveler.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access First Man by James R. Hansen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Science & Technology Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

AN AMERICAN GENESIS

Even the greatest American is an immigrant or has descended from immigrants.

—VIOLA ENGEL ARMSTRONG

America means opportunity. It started that way. The early settlers came to the new world for the opportunity to worship in keeping with their conscience, and to build a future on the strength of their own initiative and hard work. . . . They discovered a new life with freedom to achieve their individual goals.

—NEIL A. ARMSTRONG, “WHAT AMERICA MEANS TO ME,” THE READER’S DIGEST, APRIL 1975

CHAPTER 1

The Strong of Arm

Two obscure European towns took special meaning from the first human steps on another world. The first was Ladbergen, in the German province of Westphalia, about thirty-five miles from the Dutch border. Here in the northern Rhine region stood an eighteenth-century farmhouse-and-barn belonging to a peasant family named Kötter, the same common folk from which Neil Armstrong’s mother, Viola Engel Armstrong, descended. Five hundred miles to the northwest, on the Scotch-English border, lay Langholm, Scotland, home of the Armstrong ancestry. One branch of its lineage led to Neil’s father, Stephen Koenig Armstrong.

In March 1972, not quite three years after the Apollo 11 landing, Neil was named Langholm’s first-ever honorary freeman. To the cheers of eight thousand Scots and visiting Englishmen, Armstrong rode into town in a horse-drawn carriage, escorted by regimental bagpipers dressed in Armstrong tartan kilts. The glorious reception marked a reversal of fortune for the Armstrong name. Chief magistrate James Grieve, arrayed in an ermine-trimmed robe, gravely cited a four-hundred-year-old law, never formally repealed, that ordered him to hang any Armstrong found in the town. “I am sorry to tell you that the Armstrongs of four hundred years ago were not the most favored of families,” Grieve instructed. “But they were always men of spirit, fearless, currying favor in no quarter, doughty and determined.” Neil responded wryly: “I have read a good deal of the history of this region and it is my feeling that the Armstrongs have been dreadfully misrepresented.” Neil then “smiled so broadly,” said the local newspaper account, “that you could tell he loved every last one of the ancestral scoundrels.”

• • •

The Armstrong name began illustriously enough. Anglo-Danish in derivation, the name meant what it said, “strong of arm.” By the late thirteenth century, documents of the English nation—including the royal real estate records Calendarium Genealogicum—listed the archaic “Armestrange” and “Armstrang.”

Legend traced the name to a heroic progenitor by the name of Fairbairn. Viola Engel Armstrong, who immersed herself in genealogy in the years after her son’s immortal trip to the Moon, recorded one version of the fable. “A man named Fairbairn remounted the king of Scotland after his horse had been shot from under him during battle. In reward for his service the king gave Fairbairn many acres of land on the border between Scotland and England, and from then on referred to Fairbairn as Armstrong.” Offshoots of the legend say that Fairbairn was followed by Siward Beorn, or “sword warrior,” also known as Siward Digry, “sword strong arm.”

By the 1400s, the Armstrong clan emerged as a powerful force in “the Borders.” The great Scottish writer and onetime Borderlands resident Sir Walter Scott wrote four centuries later in his poem “Lay of the Minstrel” of the flaming arrows emblematic of endemic clan feuds: “Ye need no go to Liddisdale, for when they see the blazing bale, Elliots and Armstrongs never fail.” Or as another Scottish writer put it, “On the Border were the Armstrongs, able men, somewhat unruly, and very ill to tame.”

By the sixteenth century, Armstrongs were unquestionably the Borders’ most robust family of reivers—a fanciful name for bandits and robbers. Decades’ worth of flagrant expansion by the Armstrongs into what had come to be known as “the Debatable Land” eventually forced the royal hand, as did their purported crimes of burning down fifty-two Scottish churches. By 1529, King James V of Scotland marshaled a force of eight thousand soldiers to tame the troublesome Armstrongs, who numbered somewhere between twelve thousand and fifteen thousand, or roughly 3 percent of Scotland’s population. Under the pretext of a hunting expedition, James V marched his forces southward in search of Johnnie Armstrong of Gilnockie, known locally as “Black Jock.” Their fatal standoff in July 1530 was immortalized in the “Ballad of Johnnie Armstrong of Gilnockie,” which is still sung in the Borders of Scotland, and by a stone monument inscribed: “Here this spot was buried Johnnie of Gilnockie . . . John was murdered at Carlinrigg and all his gallant companie, but Scotland’s heart was ne’er sae [so] wae [woe], to see sae many brave men die.”

In his nineteenth-century collection of ballads The Border Minstrelsy, Sir Walter Scott identified William Armstrong, nicknamed “Christie’s Will,” as a lineal descendant of the famous Johnnie Armstrong of Gilnockie. Scott may have been right. Historians have inferred that Will was the oldest son of Christopher Armstrong (1523–1606), who was himself the oldest son of Johnnie Armstrong.

Walter Scott’s nineteenth-century stories do not coordinate very precisely with seventeenth-century genealogy. All information about Christie’s Will gives his birth year as 1565. His infamous kidnapping of Lord Durie, made legendary by Scott, could only have happened around 1630, when Will would have been sixty-five years old. Reportedly, the same Christie’s Will fought for the crown early in the English Civil War and died in battle in 1642; he would have been seventy-seven.

In the 1980s a private genealogical research firm in Northern Ireland suggested to Viola Armstrong that Christie’s Will was the likely founder of her husband’s family in Ulster in northern Ireland. Conveniently, he was one of the few Armstrongs with a known biography.

As early as 1604, records show a William Armstrong settling in Fermanagh, where by 1620 no fewer than twenty-five different Armstrongs (five headed by a William) lived as tenant farmers. Militia muster rolls for Ulster from the year 1630 indicate that thirty-eight Armstrong men (six named William) reported to duty.

Contrary to Viola’s conjecture, no Neil Armstrong progenitors ever settled in Ireland. They stayed in the Borderlands until they immigrated directly to America sometime between 1736 and 1743. Fittingly, for the family history of the First Man, the ancestry goes back literally to Adam.

Adam Armstrong, born in the Borderlands in the year 1638 and died there in 1696, represents Generation No. 1. Coming ten generations before the astronaut, Adam Armstrong is the great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great paternal grandfather of the first man on the Moon.

Adam Armstrong had two sons, Francis (year of birth unknown), who died in 1735, and Adam, born in Cumbria, England, in 1685. At age twenty, Adam Armstrong II married Mary Forster, born in Cumbria the same year as he. Together the couple had four children—Margaret (b. 1706), William (b. 1708), Adam Abraham (b. 1714 or 1715), and John (b. 1720)—all baptized in Kirkandrews Parish, Cumberland, England. In the company of his father, Adam Abraham Armstrong crossed the Atlantic in the mid-1730s, when he was about twenty, making them the first of Neil’s bloodline to immigrate to America. Cemetery records indicate that father Adam died in Cumberland Township, Green County, Pennsylvania, in 1749, at age sixty-four.

These Armstrongs were thus among the earliest settlers of Pennsylvania’s Conococheague (“Caneygoge”) region, named “clear water” by the Delaware tribe. Adam Abraham Armstrong worked his land in the Conococheague, in what became Cumberland County, until his death in Franklin, Pennsylvania, on May 20, 1779, when he was sixty-three or sixty-four. But already by 1760, his oldest son John (b. 1736), at age twenty-four, had surveyed the mouth of Muddy Creek, 160 miles west of the Conococheague and some 60 miles south of Fort Pitt. There John and his wife, Mary Kennedy (b. 1738, in Chambersburg, Franklin County, Pennsylvania), raised nine children, their second son, John (b. 1773), producing offspring leading to Neil. According to regional genealogy expert Howard L. Leckey, John and Mary’s sixth child, Abraham Armstrong (b. 1770), was “the first white child born on this (western) side of the Monongahela River.” While not close to being historically accurate, Leckey’s point underscores the early Anglo movement west beyond the ridge of the Alleghenies. Therein lay the major provocation for the outbreak of the French and Indian War in 1756.1

Following the Revolutionary War, thousands of settlers poured into the Ohio Country, a land that one of its first surveyors called “fine, rich, level . . . it wants nothing but cultivation to make it a most delightful country.”

In March 1799, twenty-five-year-old John Armstrong, his wife Rebekah Miller (b. 1776), their seven-month-old son David, as well as John’s younger brother Thomas Armstrong (b. 1777), his wife, Alice Crawford, and their infant, William, traveled by flatboat down Muddy Creek to Pittsburgh, then steered into the Ohio River some 250 miles down to Hockingport, just west of modern-day Parkersburg, West Virginia. The two families coursed their way up the Hocking River for 35 miles to Alexander Township, Ohio. Homesteading outside what became the town of Athens, Thomas and Alice raised six children. John and Rebekah eventually settled near Fort Greenville, in far western Ohio.

To “defend” the frontier in the early 1790s, General “Mad” Anthony Wayne built a series of forts from southwestern Ohio into southeastern Michigan. In August 1794, Wayne’s “Legion” defeated a Native American confederation led by Shawnee chief Blue Jacket at the Battle of Fallen Timbers on the Maumee River near Toledo. At Fort Greenville the next year, chiefs of the Shawnee, Wyandot, Delaware, Ottawa, Miami, Eel River, Wea, Chippewa, Potawatomi, Kickapoo, Piankashaw, and Kaskaskia relinquished claims to the entire bottom two-thirds of Ohio.

Following the War of 1812, in which many tribes had allied themselves with the defeated British, came the Treaty of Maumee Rapids in 1817, which placed all of Ohio’s remaining Native Americans on reservations, followed in 1818 by a supplemental treaty struck at Fort Barbee, near Girtystown, 42 miles north of Fort Greenville, on the St. Marys River.

Neil’s ancestor John Armstrong (Generation No. 5) and his family witnessed negotiations for what became the Treaty of St. Marys, the last great assemblage of Indian nations in Ohio. David, Samuel, John Civil, Sally, Rebecca, Mary, Jane, and Nancy settled with their parents in 1818 on the western bank of the St. Marys. From the first harvests, the Armstrongs seem to have earned enough to secure the deed to their 150-acre property, paying the two dollars per acre stipulated by the federal Land Act of 1800. St. Marys township collected taxes in 1824 from twenty-nine residents totaling $26.64, a dear ninety cents of which was paid by John Armstrong for “2 horses” and “3 cattle,” for what became the “Armstrong Farm,” the oldest farm in Auglaize County.

David Armstrong, the eldest of John’s children (b. 1798) and Margaret Van Nuys (1802–1831) were Neil’s paternal great-grandparents. It seems they did not marry. Margaret soon married Caleb Major, and David married Eleanor Scott (1802–1852), the daughter of Thomas Scott, another early St. Marys settler. Baby Stephen stayed with his mother until her premature death in March 1831, when Margaret’s parents, Rachel Howell and Jacobus J. Van Nuys, took in their seven-year-old grandson. Stephen’s father David died in 1833, followed by his grandfather in 1836.

Stephen Armstrong (Generation No. 7) received his grandfather Van Nuys’s legacy of roughly two hundred dollars in cash and goods when he turned twenty-one in 1846. The census of 1850, a year in which farmers made up 83 percent of Ohio’s 2.3 million population, listed Stephen as a “laborer.” After years working for a family named Clark, whose farm was in the low-lying “Black Swamp” of Noble Township, Stephen managed to buy 197 acres (Ohio farms then averaged only about 75). Later he secured the deed to 138 additional acres held since 1821 by the Vanarsdol family (related to the Armstrongs by marriage) as well as the rights to 80 acres held since 1835 by Peter Morrison Van Nuys, Stephen’s maternal uncle.

How the Civil War affected Stephen Armstrong is unknown. When the conflict broke out in 1861, Stephen was only thirty-four. Union service records do not indicate that he fought in the war, though by war’s end, nearly 350,000 Ohioans had joined the Union army. Of these, some 35,000, fully 10 percent, lost their lives.

Stephen married Martha Watkins Badgley (1832–1907), the widow of George Badgley and mother of two sons, George and Charles Aaron, and two daughters, Mary Jane and Hester (“Hettie”). Stephen must have met and wed “Widow Badgley,” six years his junior, by 1863 or 1864, because on January 16, 1867, Martha gave birth to Stephen’s son, Willis Armstrong, named after his guardian James Willis Major. Previously, the couple had lost two consecutive babies in childbirth.

When Stephen Armstrong died in August 1884 at age fifty-eight, he owned well over four hundred acres whose value had nearly quintupled from the 1850s purchase price of roughly fifteen dollars per acre to over $30,000—the equivalent today of over half a million dollars.

Stephen’s only natural son, Willis, inherited most of the estate. Three years later, Willis married a local girl, Lillian Brewer (1867–1901). The couple, both twenty years old, lived in the River Road farmhouse with Willis’s mother Martha. Five children were born in two-year intervals between 1888 and 1897. But in 1900 Muriel, the eldest, became crippled from a fall from her horse and later died from a perforation of the stomach, and then in 1901 Lillie died trying to give birth to yet another child.

Bereaved, Willis began a part-time mail route. One regular mail stop was at the highly respected law firm of John and Jacob Koenig. Their unmarried sister Laura Mary Louise worked as their stenographer and secretary, and, sometime in late 1903—about the time two brothers from nearby Dayton were test flying an airplane over coastal North Carolina’s Kitty Hawk—Willis began courting her. When they married in June 1905, Laura was thirty-one years old.

Willis gifted Laura not only an expensive wedding ring and precious gold lavalieres, but a honeymoon by train to Chicago, where Willis bought his new wife a dining room suite and a table service for twelve of pure white Haviland china. Returning to St. Marys, he purchased a house on North Spruce Street. Later, he moved the family into an impressive Victorian on a corner of West Spring Street.

It was here that Stephen Koenig Armstrong, Neil’s father, grew up. The first of two children born to Willis and Laura (Mary Barbara was born in 1910), the boy was welcomed on August 26, 1907, by half sisters Bernice, seventeen, and Grace, ten, and half brothers Guy, fifteen, and Ray, twelve. Laura was thirty-three when her first child was baptized, an occasion commemorated by the Koenig family with a vial of water from the River Jordan.

What most defined Stephen’s boyhood, however, were economic misfortune and a streak of family bad luck. Willis sank most of his money into an investment scheme whereby his brother-in-law John Koenig envisioned Fort Wayne as a regional interurban rail hub. Seeing a clear path to fortune, Willis mortgaged his farms.

Unfortunately for the investment, the Fort Wayne and Decatur Interurban Electric Railway was built in perfect concert with the rise of the automobile. Fatalities from a pair of highly publicized 1910 railway accidents included the man who headed the Bluffton, Geneva, & Celina Traction Company, which subsequently aborted a plan to build a new westward...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Dedication

- Preface

- Prologue

- Part One: An American Genesis

- Part Two: Tranquility Base

- Part Three: Wings of Gold

- Part Four: The Real Right Stuff

- Part Five: No Man is an Island

- Part Six: Apollo

- Part Seven: One Giant Leap

- Part Eight: Dark Side of the Moon

- Acknowledgments

- Photographs

- About James R. Hansen

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

- Photo Credits

- Cover Captions and Credits

- Copyright