![]()

![]()

THE ROOT OF WILD MADDER

![]()

AUTHOR’S NOTE

This is a work of nonfiction. All the events occurred, and the dialogue is verbatim or reconstructed from notes.

But some points need to be mentioned.

The names of a few characters have been changed at their request to avoid possible political or commercial complications. Also, the sequence of some events has been reordered for the sake of clarity and narrative flow. For similar reasons, I often have hidden the presence of my translators and others who assisted me. They were, of course, invaluable. Many of the interviews and conversations—especially in villages—would have been impossible without them. But I felt that adding these third parties in all the scenes would be an unnecessary distraction. It is in no way a judgment on their vital roles.

I do not believe that any of these considerations diminish the overall objective of this book: the faithful reconstruction of my experiences during frequent trips to Iran and Afghanistan from 1999 to 2004.

Finally, a comment on spelling and quotations.

There is no universal standard for English transliteration of Farsi or the other languages of the region. I have endeavored to use the form that appears most widely accepted or that I feel best represents the pronunciation. For example, I use Hafez, Mashhad, Turkmen, and Quran. Other sources have variants such as Hafiz, Mashad, Turkomen, and Koran, The differences, however, are never significant enough to cause confusion.

The quotations from Hafez and other writers come from various sources. For Hafez, I have tried to use mostly the translations in The Hafez Poems of Gertrude Bell. But—in the spirit of the journeys in the book—I also use verses from other editions of Hafez that I carried at the time.

![]()

TIMELINE

IMPORTANT DATES IN THE HISTORY OF THE PERSIAN WORLD

- c. 8000 B.C.: Permanent settlements established in area of present-day Iran.

- c. 3000 B.C.; First urban centers begin to develop in present-day Afghanistan.

- 1700 B.C.—1200 B.C.: Beginnings of Zoroastrianism, according to most sources.

- c. 600 B.C.—c. 330 B.C.: Achaemenian dynasty. The first clear Persian Empire. Named for Achaemenes, an Aryan chieftain in southwestern Iran. Kings included Cyrus the Great, Darius, and Xerxes. The empire had contact with the Greeks through war and diplomacy, which were among the first significant and sustained exchanges between East and West.

- 334 B.C.; Alexander the Great enters Persia.

- c. 323 B.C.—c. 60 B.C.: Greek-influenced Seleucid dynasty established following Alexander’s death. Named for Seleucus I, a Macedonian general under Alexander.

- c. 247 B.C.—c. A.D. 225: Tribal rulers known as Parthians begin taking control of Persian lands. Parthia was named for a region in Iran’s present-day northeast.

- c. 224—c. 650: Sassanian dynasty. Rulers seek to revive culture of the Achaemenian kings and promote Zoroastrian faith. Dynasty named after an ancestor, Sasan, who was claimed by the first king, Ardashir I. Arab forces bringing Islam defeat last Sassanian ruler.

- 820—1220: Series of Persian rulers gradually diminishes Arab influence. Modern Persian language takes shape.

- c. 1220: Mongol conquerors under Genghis Khan invade Persian territory.

- Late 1300s: Timur, or Tamerlane, begins conquest of Persia.

- c. 1500—1720s: Safavid dynasty rules Persia. The royal line drew a connection to Shaykh Safi od-Din, a Sufi leader who claimed family ties to an earlier Shiite imam. Period of significant artistic and architectural advances. Safavid rulers brought dominance of Shiite Islam. The dynasty begins to collapse with losses against invading Afghan tribesmen.

- 1779—1925: Qajar dynasty begins after Mohammad Qajar wins power struggle among feuding tribes and rulers. Persian political and commercial contacts with Western world increase. An army officer, Reza Khan, takes control of government in a 1921 coup.

- Mid-1800s: Afghans assert independence. British battle to maintain influence.

- 1893: The Durand Line fixes border between Afghanistan and British-controlled subcontinent.

- 1925: Coup leader in Persia declares himself king and takes the name Reza Shah Pahlavi, the name of the language from Sassanian times.

- 1935: Reza Shah Pahlavi officially renames country Iran.

- 1941: Allies occupy Iran, forcing Reza Shah to abdicate in favor of his son, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, who becomes the new shah.

- 1979: Islamic Revolution in Iran. Soviet invasion of Afghanistan.

- 1989: Last Soviet troops withdraw from Afghanistan.

- 1996: Taliban begins taking control of Afghanistan.

- May 1997: A political moderate, Monammad Khatami, elected president of Iran.

- June 2001: Khatami reelected in landslide.

- Late 2001: Taliban toppled in U.S.-led attacks following refusal to surrender Osama bin Laden.

- February 2004: Conservatives regain control of Iranian parliament in contested elections.

- June 2005: Arch-conservative Mahmoud Ahmadinejad wins Iranian presidential elections.

Oh, you painters who ask for a technique of color—study carpets and there you will find all knowledge.

—Paul Gauguin

![]()

A PROLOGUE MADDER AND BONE

I came a long way to stand in a field of wild madder.

My driver stopped. I stepped off the one-lane road that pierced the dust bowl of central Iran. Then I walked down a path. It slithered atop a narrow ridge.

I liked that. It gives an idea of how I ended up here: definitely not a straight line and always struggling to keep some balance.

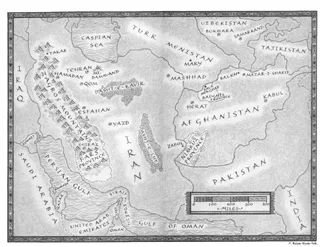

I had set out to write about carpets and the people who make them, sell them, cherish them, and, above all, see them with the same wonder that I do. At first, as a journalist, I poked around the edges of their lives on frequent assignments to Iran and Afghanistan, two important landmarks on the vast carpet map. But when I started to look more closely, I confronted the dilemma of any cartographer: what features to enhance and what details to omit. In other words, how do you find the right scale and relevance amid unlimited possibilities?

This is my attempt.

The things that intrigued me—handwoven carpets, the art of making dyes from nature and the expressions of beauty and faith they produce—already had an old and rich topography. There were imperial kings and swordsmen, folktales and cauldrons of steaming colors, lumbering caravans and cunning merchants. And—perhaps most delightful of all—mystic poets whose images dance in purple shadow and amber light. It could be rewarding enough just to explore the ground that others had covered and look for scraps and stories they had missed. But there was more out there if I searched harder. I had it on good authority.

A leafy little plant called madder told me so. I had been reading about its rich history as a dyestuff for carpets. Then I came across a quirky reference that is all but forgotten.

It can turn our bones red.

I first spotted this in a medical paper on skeletal development. It’s now just an obscure footnote from nearly three centuries ago. But at the time—as the Enlightenment was driving away medieval phantoms—it caused a sensation and upended prevailing ideas about physiology. To me, this bit of historical flotsam was still impressive.

I decided madder would serve as my polestar. It would help me negotiate the noisy bazaars, musty workshops, distant villages, and other places I couldn’t even yet imagine.

Madder seemed an ideal beacon to keep me on course. I could drift off on any detour in the carpet world and never really lose sight of madder’s influence and the fiery palette held in its roots.

The bone story stayed my favorite. But I’d learn there were many others.

They flow generously from sources both illustrious and arcane. Madder’s diary goes back as far as history’s earliest written pages. And it most likely tumbles even further into the past.

The madder root—dried and ground into dyers’ powder—was carried by Phoenician traders and mentioned in Egyptian hieroglyphics. The Greek historian-wanderer Herodotus noted that it produced the striking vermilion shades on the goatskin cloaks of Libya’s most elegant women. The Bible refers to madder as pu’ah, which some scholars believe was also a lullaby sound used to calm crying infants. To the Romans, it was rubia, which has endured as its scientific name. Pliny the Elder believed the most bountiful madder flourished in gardens near Rome.

Genus Rubia, family Rubiaceae, order Rubiales. The linguistic lineage fans out in many directions: ruby, rubric, rubella.

Alchemists pored over its properties in hopes of coaxing magic from nature. Artists made their canvases glow with madder-based glazes. As the Dutch master Jan Vermeer was finishing his famous Girl with a Red Hat in 1666, colonies were taking root across the Atlantic that would rebel a century later against the British crown. The soldiers of King George III sent to fight the American patriots wore madder-dyed red coats.

Healers, too, were drawn to the madder root’s tentacles, which are full of swollen joints and crooked angles like those of an arthritic patient. The colors it bestowed must have seemed too powerful, too close to our own blood, to be medically benign. Extracts were prescribed—with little recorded success—for complaints ranging from jaundice to irregular menstruation to chronic bruising.

Then in about 1735 a British surgeon named John Belchier chronicled a remarkable observation. Animals fed madder leaves had red-tinged bones. And not everywhere. Only in the places where bones were growing and developing.

Belchier’s research won...