![]()

PART ONE

WHAT SHOULD WE BELIEVE?

![]()

1

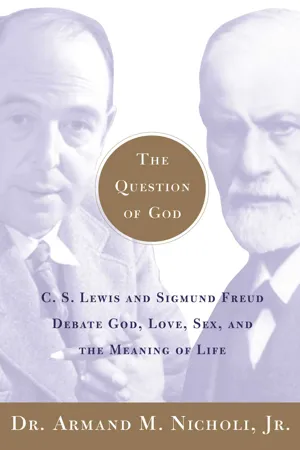

THE PROTAGONISTS

The Lives of Sigmund Freud and C. S. Lewis

Although C. S. Lewis, a full generation younger than Sigmund Freud, embraced Freud’s atheism during the first half of his life, he eventually rejected that view. When Lewis began teaching at Oxford, Freud’s writings had already influenced many intellectual disciplines, including Lewis’s field, literature. Lewis knew well all of Freud’s arguments—perhaps because he used them to bolster his position when he himself was an atheist. In his autobiography he writes: “The new Psychology was at that time sweeping through us all. We did not swallow it whole . . . but we were all influenced. What we were most concerned about was ‘Fantasy’ or ‘wishful thinking.’ For (of course) we were all poets and critics and set a very great value on ‘Imagination’ in some high Coleridgean sense, so that it became important to distinguish Imagination . . . from Fantasy as the psychologists understand that term.” Rare indeed is the person whose views never change throughout his life. Before we compare the views of Lewis and Freud, therefore, we need to know something about how they reached them.

Freud’s Background

On May 6, 1856, in the town of Freiberg, Moravia, Amalia Freud gave birth to a son. Little did she realize her child would someday be listed among the most influential scientists in history. Her husband, Jacob, named him Sigismund Schlomo and inscribed these names in the family Bible. The young boy eventually dropped both of these names. He never used “Schlomo,” his paternal grandfather’s name, and, while a student at the University of Vienna, changed “Sigismund” to “Sigmund.” A nursemaid took care of the young Freud for the first two and a half years of his life. A devout Roman Catholic, she took the young boy to church with her. Freud’s mother, many years later, told Freud that on returning from church he would “preach and tell us what God Almighty does.” The nursemaid spent considerable time with Freud, especially when his mother became pregnant and delivered a younger sibling. Freud considered her a surrogate mother and became very attached to her. When less than two years old, he lost his younger brother, Julius, whose sickness and death must have absorbed all of his mother’s time and left him almost totally in the care of his nanny. He wrote that although “her words could be harsh,” he nevertheless “loved the old woman.” In a letter to Wilhelm Fliess, an ear, nose, and throat specialist with whom Freud developed a close friendship for several years, he stated “in my case the ‘prime originator’ was an ugly, elderly, but clever woman, who told me a great deal about God Almighty and hell and who instilled in me a high opinion of my own capacities.” During this time the nanny, after being accused of stealing, left the household suddenly. As an adult, Freud would dream about her.

Scholars have speculated that Freud’s antagonism to the spiritual worldview and specifically to the Catholic Church stemmed in part from his anger and disappointment at being left by the Catholic nanny at a critical time in his life. Freud acknowledged that “if the woman disappeared so suddenly . . . some impression of the event must have been left inside me. Where is it now?” He then also recalled a scene that had been “for the last twenty-nine years turning up in my conscious memory . . . I was crying my heart out . . . I could not find my mother . . . I feared she must have vanished, like my nurse not long before.” Still, it is itself a Freudian stretch to assume that his feelings toward the church were formed by one person’s departure from his life.

What is true is that the nanny exposed Freud to Catholic practices. When the nanny took the little boy to mass, Freud apparently observed worshippers kneeling, praying, and making the sign of the cross. These early childhood impressions may be what he had in mind when, as an adult, he wrote papers comparing religious practices with obsessive symptoms and referring to religion as the “universal obsessional neurosis.” They may also have been Freud’s first exposure to music, Rome, and the holidays of Easter and Pentecost (also known as Whitsunday—the celebration of the descent of the Holy Spirit upon the disciples). Although Freud disliked music, he appeared to possess a strange attraction to Rome and an unusual awareness of these two holidays. He mentioned them often in his letters. He writes of his “longing for Rome,” of his wish to spend “next Easter in Rome,” and how he “so much wanted to see Rome again.”

Sigmund Freud grew up in an unusual, complicated family. Freud’s father Jacob married Amalia Nathansohn when she was still a teenager and he was forty years old and already a grandfather. Amalia was Jacob’s third wife. Jacob had two sons from his first marriage, one older than Amalia, and one a year younger.

Freud’s father had been educated as an Orthodox Jew. He gradually gave up all religious practice, celebrating only Purim and Passover as family festivals. Nevertheless, he read the Bible regularly at home in Hebrew, and he apparently spoke Hebrew fluently. In his autobiography, written when almost seventy years old, Freud recalled, “My early familiarity with the Bible story (at a time almost before I had learnt the art of reading) had, as I recognized much later, an enduring effect upon the direction of my interest.” During several visits to the Freud home in London, I spent time alone in Freud’s study perusing his bookshelves. I noticed a large copy of a Martin Luther Bible. Many of Freud’s numerous biblical quotations suggest that he read this translation. The Bible that he read as a boy, however, appears to be the Philippson Bible, consisting of the Old Testament and named after a scholar of the Reform Movement that led to Reform Judaism. On Freud’s thirty-fifth birthday Jacob Freud sent his son a copy of the Philippson Bible with the following inscription in Hebrew:

My dear Son:

It was in the seventh year of your age that the spirit of God began to move you to learning. I would say the spirit of God speaketh to you: “Read in my Book; there will be opened to thee sources of knowledge and of the intellect.” It is the Book of Books; it is the well that wise men have digged and from which lawgivers have drawn the waters of their knowledge.

Thou hast seen in this Book the vision of the Almighty, thou hast heard willingly, thou hast done and hast tried to fly high upon the wings of the Holy Spirit. Since then I have preserved the same Bible. Now, on your thirty-fifth birthday I have brought it out from its retirement and I send it to you as a token of love from your old father.

Freud naturally associated the spiritual worldview with his father. His feelings toward his father were at best ambivalent. Unlike him, Freud never learned to speak Hebrew and knew only a few words of his mother’s Yiddish.

Jacob Freud struggled to make a living as a wool merchant, and the entire family occupied a single rented room in a small house. The Freuds lived above the owner, a blacksmith, who occupied the first floor. During the time of Freud’s birth the population of Freiberg—later known as Príbor in modern Czechoslovakia—ranged from about 4,000 to 5,000. The Catholic population of Freiberg far outnumbered the Protestant and Jewish populations of about 2 to 3 percent each.

When he was about three years old, in 1859, Freud and his family-moved to Leipzig, and then a year later to Vienna. He lived and worked the rest of his life in Vienna—until in 1938, when eighty-two years old, after the Nazi invasion, he escaped to London with the help of colleagues, the American secretary of state, and President Franklin Roosevelt.

During his adolescent years in Vienna, Freud studied Judaism under Samuel Hammerschlag, who emphasized the ethical and historical experience of the Jewish people more than their religious life. Hammerschlag remained a friend and benefactor to Freud for many years. When he was fifteen, Freud also began corresponding with a friend named Eduard Silberstein. These letters, extending over a full decade, give us some insight into the theological and philosophical thoughts and feelings of the young Freud, especially on the question of whether or not an Intelligence exists beyond the universe. Silberstein was a believer who became a lawyer and married a young woman whom he sent to Freud for treatment of her depression. After arriving at Freud’s office, she told her maid to wait downstairs. Instead of going to Freud’s waiting room, she went up to the fourth floor and jumped to her death.

When Freud entered the University of Vienna in 1873 and studied under the distinguished philosopher Franz Brentano, a former Catholic priest who left the priesthood because he did not accept the infallibility of the pope, he wrote about it to Silberstein. Brentano made a profound impression on the young Freud. Eighteen years old, Freud exclaimed in a letter to his friend: “I, the godless medical man and empiricist, am attending two courses in philosophy . . . One of the courses—listen and marvel!—deals with the existence of God, and Prof. Brentano, who gives the lectures, is a splendid man, a scholar and philosopher, even though he deems it necessary to support his airy existence of God with his own expositions. I shall let you know just as soon as one of his arguments gets to the point (we have not yet progressed beyond the preliminary problems), lest your path to salvation in the faith be cut off.”

A few months later Freud comments further on his impressions of Brentano: “When you and I meet, I shall tell you more about this remarkable man (a believer, a teleologist . . . and a damned clever fellow, a genius in fact) who is in many respects, an ideal human being.” Under Brentano’s influence Freud wavered and considered becoming a believer. Freud confided to Silberstein the strong influence Brentano had on him: “. . . I have not escaped from his influence—I am not capable of refuting a simple theistic argument that constitutes the crown of his deliberations . . . He demonstrates the existence of God with as little bias and as much precision as another might argue the advantage of the wave over the emission theory.” Freud also encouraged Silberstein to attend Brentano’s lecture: “The philosopher Brentano, whom you know from my letters, will lecture on ethics or practical philosophy from eight to nine in the morning, and it would do you good to attend, as he is a man of integrity and imagination, although people say he is a Jesuit, which I cannot believe . . .”

Then Freud made a startling quasi-admission: “Needless to say, I am only a theist by necessity, and am honest enough to confess my helplessness in the face of his argument; however, I have no intention of surrendering so quickly or completely.” In the same paragraph, he made a contradictory statement: “For the time being, I have ceased to be a materialist and am not yet a theist.” This confusion and ambivalence would stay with him, despite his many ringing pronouncements in favor of atheism.

In another letter a few weeks later, Freud continued to share his struggle: “The bad part of it, especially for me, lies in the fact that science of all things seems to demand the existence of God . . .”

Freud may have repressed the experience of becoming a “theist by necessity.” When he was seventy years old, in an address to the B’nai B’rith (Sons of the Covenant), he stated: “What bound me to Jewry was (I am ashamed to admit) neither faith nor national pride, for I have always been an unbeliever . . .” If Freud found the arguments by Brentano for the existence of God so compelling, what made him so reluctant to accept them, to “surrender” to reasoning he was unable “to refute”? Some answers to these questions may lie among the other influences on the young Freud during his long years of medical education.

First, in his letters to Silberstein, Freud mentioned reading another philosopher, Ludwig Feuerbach. “Feuerbach is one whom I revere and admire above all other philosophers,” Freud wrote his friend in 1875. Ludwig Feuerbach, born in 1804, studied theology at the University of Heidelberg. A student of Hegel, he wrote books critical of theology, stating that one’s relationship to others—the “Iand-thou” relationship—was more compelling than one’s relationship to God. Although he claimed to be a believer, his writings reinforced the atheism of both Marx and Freud. His main thesis in The Essence of Christianity is that religion is simply the projection of human need, a fulfillment of deep-seated wishes.

The purpose of his book, Feuerbach wrote, was “the destruction of an illusion.” He summarized the work in his conclusion: “We have shown that the substance and object of religion is altogether human; we have shown that divine wisdom is human wisdom; that the secret of theology is anthropology; that the absolute mind...