- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

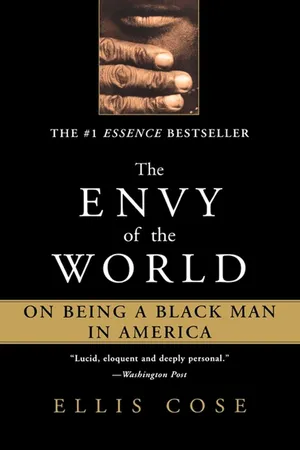

About this book

With a compassionate eloquence reminiscent of James Baldwin's Letter to My Nephew, Ellis Cose presents a realistic examination of the challenges facing black men in modern America.

Black men have never had more opportunity for success than today—yet, as bestselling author Cose puts it, "We are watching the largest group of black males in history stumbling through life with a ball and chain." Add to that the ravages of police brutality, murder, poverty, illiteracy, and the widening gap separating the black "elite" from the "underclass," and the result is a paralyzing pessimism. But even as Cose acknowledges the systemic obstacles that confront black men, he refuses to accept them as reasons for giving up; instead he rails against the destructive attitude that has made academic achievement a source of shame instead of pride in many black communities—and outlines steps black males can take to enhance their odds for success.

With insightful anecdotes about a broad range of black men from all walks of life, Cose delivers a warning of the vast tragedy that is wasted black potential, and a call to arms that can enable black men to reclaim their destiny in America.

Black men have never had more opportunity for success than today—yet, as bestselling author Cose puts it, "We are watching the largest group of black males in history stumbling through life with a ball and chain." Add to that the ravages of police brutality, murder, poverty, illiteracy, and the widening gap separating the black "elite" from the "underclass," and the result is a paralyzing pessimism. But even as Cose acknowledges the systemic obstacles that confront black men, he refuses to accept them as reasons for giving up; instead he rails against the destructive attitude that has made academic achievement a source of shame instead of pride in many black communities—and outlines steps black males can take to enhance their odds for success.

With insightful anecdotes about a broad range of black men from all walks of life, Cose delivers a warning of the vast tragedy that is wasted black potential, and a call to arms that can enable black men to reclaim their destiny in America.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Envy of the World by Ellis Cose in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Ciencias sociales & Historia de Norteamérica. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

A Song of Celebration

Let me begin this section with a simple assertion: Black men are not an “endangered species,” not in the sense of, say, the peregrine falcon or the bog turtle, whose longterm existences on Earth are in question. We stand nearly seventeen million strong, an ever-growing extended family of black boys and men. We are far too resilient and much too entrenched for the word “endangered” to apply. Precarious as our status may be in many respects (and I will have much more to say about this later), we are not about to disappear. In our centuries-long odyssey as a new race in a New World, we have learned a thing or two about survival, about succeeding against even the longest of odds.

Because the barriers have been so high, we have learned to savor our achievements. We are even learning to appreciate ourselves, though the lesson of self-acceptance has not always been an easy one. We are, after all, only a couple of generations removed from the time when black was anything but beautiful; when even our natural physical selves could engender a certain self-loathing—at least among those of us with “nappy” hair and dusky skin.

I recall as a child of perhaps seven or eight coming across some pictures of Africans in a book and noting that they seemed to be significantly darker than almost anyone that I knew. In trying to reason out why that was so, I drew on my rudimentary grasp of evolution. I concluded that here, under the American sky, which was presumably more benign than the African sun, black people, no longer in need of heavy-duty solar protection, were evolving. We were becoming lighter, and in time, I concluded, we probably would become something approximating white. That realization brought a certain amount of comfort. For though my grasp of science clearly was flawed, my sense of the world was pretty much on target. And in that world of the late fifties and early sixties, good hair was straight, light boys were cute, and great wealth (which to a kid in the Chicago housing projects meant such things as a house with a lawn and a bedroom of one’s own) was the special preserve of whites. In the universe of wondrous things, as I understood from my time watching television and the occasional movie, blacks were almost as rare as jellyfish in a desert.

That particularly skewed televised view of America began to change during the great civil rights awakening, when black people pointed out the obvious: We were—and always had been—an essential element of the United States, and the wisest and most courageous among us demanded that so-called mainstream America stop pretending that we were interlopers in our own country.

Before the great awakening, before Martin and Malcolm and four little dead girls in a church in Birmingham forced America to glimpse the truth, it was possible to believe that we would stay forever in our slave-society assigned place. Even the geniuses in Hollywood, with all their talent and vision, seemed incapable of conjuring up a world where blacks were equal to whites.

I was reminded of that late one evening when I happened to catch a broadcast of a science-fiction movie from 1951 entitled When Worlds Collide. An errant star (spotted by a brilliant astronomer in South Africa) was hurtling toward Earth, and the best minds of the universe saw no way to stop it. Unwilling to accept mankind’s end, which the imminent collision would bring about, the world’s scientists searched frantically for a solution. They soon realized that the very instrument of mankind’s death, the doomsday star, might be the key to human salvation, that a small planet circling the star seemed capable of supporting human life. The first challenge was to build a spaceship that could reach that star; the second was to choose the forty or so human beings charged with beginning civilization anew.

Those selected were young and suitably beautiful—and every one of them was white. The new Eden, as envisioned by director Rudolph Maté, had no place for blacks (or Asians, or apparently anyone else who would have felt unappreciated in apartheid-era South Africa). I have no idea what concepts informed Maté’s racial philosophy, or even whether he consciously had one. I assume that he held no conscious malice toward blacks or any race, but that he was simply oblivious to the possibility that in the new paradise, in a regenerated perfect world, our presence might be desired.

The year of that movie’s release also saw the publication of Invisible Man, Ralph Ellison’s classic journey through American society. I discovered the novel as a teenager, and I was hooked from the opening passage, in which the protagonist declares that he is invisible “simply because people refuse to see me.”

The words resonated, not merely because they were written beautifully but because they described so well what I had so often felt. Fact is, they sum up pretty much what virtually any teenage soul perceives. Still, to me it seemed the words were aimed specifically at black boys like me, boys whose value was unrecognized, boys who had to cope with teachers, cops, policemen, and strangers who truly couldn’t see us through the stereotypes in their minds, who couldn’t imagine a world in which black boys could be as worthy as whites, who saw—to paraphrase Ellison—our surroundings, figments of their imagination, indeed, everything and anything but us.

Thank God that, in the decades since I first picked up that book, attitudes about us have shifted, including, most importantly, our own. Hardly anyone these days doubts that we are an integral part of the human family, hardly anyone disputes the fact that we (some of us, anyway) are awesomely talented souls. But far too often we are still underestimated or told to limit our ambitions, and are forced into that handful of slots where black men are expected to excel. We are athletes, rappers, preachers, singers—and precious little else. Or so is the uninformed assumption, though in truth our talents are as multifarious as our dreams, as uncontainable as rainbow rays shooting across the sky. So let us celebrate all we have done and all that we can be, and let us remember that there always have been black men of sterling character and accomplishment, men as diverse as Frederick Douglass, orator, author, statesmen, and abolitionist, and Dr. Charles Drew, the preeminent blood plasma researcher who organized America and England’s plasma programs during World War II. Talented as such men may have been, society embraced them only grudgingly, often not at all, and certainly not in any significant numbers. At long last, that is changing. In an age when black men increasingly are reaching for the stars, and where a couple of us literally have soared into space itself, America finally has begun to acknowledge, and even to rejoice in (albeit selectively), our existence. And the list of achievers is growing apace. It includes men such as Benjamin Carson, a product of Detroit’s inner city who became director of pediatric neurosurgery at Johns Hopkins Hospital, and who is renowned, among other things, for separating the Binder Siamese twins in 1987 as the world watched and prayed. And it includes countless others, many less widely acknowledged, who are doing everything from rescuing former gang-bangers from the streets to inspiring young black kids to study science and math.

So let me single out a couple of modern pioneers, not because they are different from the rest of us (in many respects, they are not), but because they are living examples of what we can achieve, with a little luck, ambition, applied intelligence, and sweat.

Maurice Ashley, America’s first and so far only black grand master in chess, is a compact man, with a lithe build, glasses, cornrowed hair (at least one afternoon when we talked), and the suggestion of a goatee. He was born in Jamaica in 1966. His parents split up when he was two, and along with his brother and sister, he remained in Jamaica with his grandmother while his mom came to Brooklyn to create a life for them all. She found a clerical job, saved some money, and sent for them when he was twelve.

Ashley had always been an A student and had always been good at games, having learned chess as a child from his older brother. But it was not until he arrived at Brooklyn Technical High School, a highly regarded and selective public school, that he got serious about the game. His interest was fueled in large measure by Chico, a friend from Haiti who dreamed of getting on the school’s chess team. But to get on the team, Chico had to rise in the rankings, which he could only do by beating members of the chess club. So he urged Ashley to join the club, with the intention of trouncing him and using his defeat to climb higher on the ladder. Unaware of Chico’s motivation, Ashley accepted his invitation. Chico challenged and promptly won, but Ashley didn’t much care. By then chess had become his obsession.

He would begin playing around three o’clock, when his classes let out, and stop just before seven, when train passes expired. After doing his homework, he would play chess for another hour and a half. On weekends, he would play all day. Ashley was so involved in chess that his grades began to drop. Instead of As, he got Bs. He was not on the team (good as he was, he was not yet that good), but chess had become the center of his life. He loved the competition and felt his game improving, and even dreamed of making a living at it. During his last year of high school, 1983, he boasted to a friend that he would be a grand master within ten years.

He now looks upon that boast as almost comical. “I didn’t know what it took to be a grand master, but I had this passion and this love for the game.” He also sees clearly, as he did not at the time, just how audacious his ambition was, and how high the odds were against his achieving it. Most grand masters, as Ashley puts it, are “born and bred” to play the game. Much like champion figure skaters who, from the time they can tie on a skate, spend hours a day gliding around the rink, future chess grand masters are molded from the age of five or six, competing in tournaments at a time they barely have learned their ABCs. Ashley was starting awfully late in the game. And he was doing so without the financial and professional support that middleclass white chess whizzes take for granted.

Yet, whereas he could have been pursuing medicine, law, engineering, or any of scores of fields in which blacks had long excelled, he focused only on chess: “I was sort of breaking the mold … this young black kid thinking he’s going to be a chess player, putting all of his eggs in this one basket.” There was something even mystical in his devotion, a sense that he had a “rope of destiny pulling me along.” And since there were no black archetypes at the highest level in organized chess, he went looking for trailblazers elsewhere, for black pioneers who, despite the isolation, had become champions in their sports. Their examples, he figured, would stiffen his own resolution and reassure him that “what I was doing wasn’t completely crazy.” Debi Thomas, the Olympic medalist and figure skater, along with tennis greats Lori McNeil and Zina Garrison, were among those from whom he drew inspiration. But it was Arthur Ashe who “touched my soul.”

It’s easy to see why Ashley was so drawn to Ashe, the Wimbledon champ and soft-spoken activist, the thinking man’s athlete acutely aware of the racial burdens sitting on his slender shoulders. He was a man who profoundly believed that he had a duty to ignore the limits on aspirations imposed on him and other blacks by a society blind to black potential. “My potential is more than can be expressed within the bounds of my race or ethnic identity,” wrote Ashe, in his memoir, Days of Grace.

People have told Ashley that they see something of Ashe’s spirit in him. And it is not a bad spirit for a chess player to have, that of a gentle fighter who never learned to crumble before a challenge. By the time Ashley arrived at City College of New York (with a short stop en route at New York City Technical College), his hard work and irrepressibly persistent spirit had lifted his level of play. “I had been working at chess consistently—reading, playing, getting into tournaments. My talent merged with my work ethic.” He also had discovered, in the Black Bear School of Chess, mentors of his own race in his chosen sport.

The Black Bear School was not a formal institution but a group of men who met in Brooklyn’s Prospect Park to play what Ashley calls a ferociously macho, intensely competitive brand of chess. Though the men were not officially ranked, and all worked at other jobs, many played at the master and expert level, and their passion for the game rivaled his own. One of the Black Bears, Willie Johnson, an electrician twenty years Ashley’s senior, became something of a mentor and, eventually, godfather to his daughter.

Ashley became captain of the CCNY team and received his master’s rating from the United States Chess Federation in 1986. His mother, a single parent who worked as a file clerk at New York University, was proud but less than impressed. “Do you get money with that?” she asked him, her way of pointing out that, although he might be among the top 4 percent of players in the nation, his dreams of greatness and glory through chess were not exactly paying any bills. “You better get a degree, fool,” she said.

The baccalaureate in creative writing did not come until seven years later (“That degree was for my mother”) but in the interim his chess fantasies blossomed into a career. In the late eighties he began coaching clients for money and, as his reputation spread, he caught the eyes of the American Chess Federation, which provided for him to coach junior high school teams in Harlem and the South Bronx.

The Raging Rooks, the team at Harlem’s Adam Clayton Powell Jr. Junior High School that he coached in 1991, was not anyone’s idea of a typical chess team. Six out of the eight members had no father in the home. The team captain was living temporarily in a homeless shelter because a junkie had burned down his apartment building. For many of its members, the club was a haven, hollowed ground far removed from the perils and chaos outside. “In that place, nothing brought you down,” Ashley recalls. “The attitude was always positive, about success.”

Under Ashley’s guidance, the Raging Rooks took the 1991 National Junior High School championship, propelling their coach into a media spotlight whose incandescence still astounds him. The New York Times ran a front-page feature, and media outlets from across America focused on the miracle worker behind the Harlem chess champs. Among the calls spawned by the extensive publicity came one from Mott Hall Intermediate School in the Harlem-Washington Heights community. “You have to come to my school,” said the principal.

Around that time, Ashley had a falling-out with the American Chess Federation. The Harlem Educational Activities Fund, a nonprofit founded by builder Daniel Rose, became Ashley’s new angel. With HEAF’s backing, Ashely launched a chess program at Mott and repeated the magic, taking their Dark Knights to two Junior Varsity Division championships—in 1994 and 1995. Meanwhile, in 1993, he had ascended to the rank of international master, but despite all his success as a coach, he felt unfulfilled. By 1997, he was fighting depression. “A gaping hole” had opened in his spirit, he confides. “It was the lowest point in my life.”

Ashley had proved himself as a coach, and had married and fathered a daughter, but he had not achieved the goal he had set for himself so many years before. It was as if the parade were passing by without him, a feeling that only intensified that April when Tiger Woods, at the age of twenty-one, won the master’s by twelve strokes. Woods’s feat was unprecedented for anyone, made all the more notable because a person of color, of African ancestry, had achieved it.

Ashley felt more than a twinge of envy. “I said, ‘That could be me. I should be making more noise.’ ” He talked to Courtney Welsh, his supervisor at HEAF, who suggested he talk to the ultimate boss. Daniel Rose granted him a leave with pay and told him to do whatever he needed to do in order to realize his dream.

Ashley hired a coach and launched himself on a routine of international tournaments and concentrated study that culminated in New York in March 1999. In a tournament at the esteemed Manhattan Chess Club International, he racked up enough points to take his seat among the grand masters of the universe. The official title would be conferred that October. The journey that had begun some sixteen years earlier was at long last over.

It was snowing that fourteenth of March, and New York, to the new grand master’s eyes, had never looked, well, grander. He was filled with ecstasy and also a bit awestruck at where his audaciousness had taken him, at the fact that a “crazy kid out of Jamaica with a stupid dream” had triumphed in the end. But he did not rest on his laurels for long. Later that year, with HEAF’s support, he founded the Harlem Chess Center, a place where neighborhood kids can get instruction, inspiration, and license to keep their dreams alive. “The biggest thing they suffer from is a lack of support,” says Ashley. “Like every kid, these kids dream big at first. As you grow, you begin to curb the scope of your dream. You [measure] reality and grow into it.”

Despite having achieved his major goal, Ashley continues to aim upward. When I visited him in January 2001, he was ranked seventeenth in the nation. He was hoping to make it into the charmed circle of the top twelve, which would guarantee him a shot at the U.S. championship. He hoped he could do it within a year, but figured that two might be more realistic. And though he has cut back his coaching schedule, the Dark Knights continue to rack up national championships.

That fills Rose with an almost paternal pride. “Our teams, in which there is not a Caucasian face, have the confidence that comes from winning,” he boasts. “When our kids are number one in the United States in chess, you don’t have to tell them they’re good. They know it.” Chess, for him, is a means to an end, a way “to tell them they can be just about anything.”

Franklin Delano Raines has lived his life proving that lesson. His résumé is a profile in high achievement: graduate of Harvard University and Harvard Law School; Rhodes Scholar; former partner of Lazard Freres & Company, a big-time investment banking firm; former director of the U.S. Office of Management and Budget; and currently head of Fannie Mae, America’s third largest corporation—which, in naming Raines chairman and CEO in late 1998, became the first Fortune 500 corporation ever to put a black man in charge.

Not bad for a boy from the poor side of Seattle. But if Raines’s ascendance was not exactly foreordained, he did have greatness thrust upon him, in a sense, virtually at the moment of his birth. Born the fourth of six children in January 1949, his parents named him Franklin Delno—Delno being his father’s first name. But “Franklin Delano” was recorded on his birth certificate, making him the namesake of America’s revered thirty-second president, a man whose intellect and accomplishments Raines would come to admire. As head of an institution created during Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s administration to shore up a housing industry sagging under the weight of the Great Depression (originally an agency of the Federal Housing Administration, Fannie Mae became a private company in 1968), Raines arguably is carrying on the late president’s work.

In searching for the secret to Raines’s success, many have remarked on the example set by his father, a man who spent five years building, brick by brick, the house that was to be their home. The entire process, recalls Raines, actually took much longer than five years, since the property lay vacant for some time after his dad acquired it, and it took a year and a half just to put in the foundation: “Even when we moved in, it wasn’t totally finished.” The story finds its way into many of Raines’s profiles, as an example of how the father’s attributes of persistence and patience naturally took root in the son. Yet, Raines is no patient plodder; he is just the opposite, a man whose impatience is so overpowering that it blew him past the competition with the force of a volcano shooting toward the sky.

His father, who did not graduate from high school, was a mechanic and eventually a parks maintenance supervisor. His mother, who only finished the sixth grade, at one point worked in a chicken house and ended up as a janitor at Boeing. The Rainier Valley neighborhood in which Raines grew up was a mixed-race and working class community on the edge of the central area of Seattle. His neighbors were mostly blacks and Italians, with a few Asians and Jews in the mix. Public housing sat just to the north and the south.

The family consisted not only of Franklin, his parents, and his five siblings, but also a cousin whose mother had died who came to live with them when he was three. Money was never plentiful. For a time the family was on welfare. Franklin himself worked at Irving’s Grocery Store, a job he began when he was eight years old. He went to the store every day after school and was there all day Saturday, for which he was paid two dollars a week, a sum that had risen to ten dollars weekly by the time he retired from the grocery business at the age of fourteen.

His family did not especially stress academic achievement: “We went to school because that was what you did.” But though his parents were not pushing him toward academic stardom, others were: “Teachers clearly had very high expectations, for me in particular.” And among those teachers in his largely nonwhite public grade school (it was roughly 80 percent black, 15 percent Asian American, and 5 percent white, Raines recalls, with the vast majority of the white kids in the neighborhood attending parochial school) black teachers especially pushed Raines to achieve. “You can’t screw up,” they told him. And he couldn’t let them down.

From the beginning, he was grouped with the smart kids, but he noticed, over time, that many of his black peers got weeded out. The fast track, more and more, became the province of Asians, with a few blacks sprinkled in. He is not sure exactly why that happened, but (like Ashley) sees at least part of the phenomenon as a “problem of high expectations.” Everyone was expected to do well as children, but as they got older, blacks were expected to do less well.

Nonetheless, he does not remember, as a child, focusing on racial differences. Although it was mostly white kids “constantly coming over to fight us,” he saw those skirmishes less as racial conflicts than as public school versus private school fights. He did notice economic disparities: “Some kids had more stuff…. Most kids didn’t work. I was working.”

In high school, the racial proportions flipped. Approximately 20 percent of the students were black, 15 percent Asian American, and the rest were white. But Raines did not feel intellectually intimidated: “I had grown up competing and playing with white kids.” He became state debate champion, quarterback and captain of the football team, and president of the student body.

Franklin High School, as Raines remembers it, was ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Acknowledgments

- Contents

- 1 A Song of Celebration

- 2 Keeping It Real

- 3 Too Cool for School

- 4 If We Don’tBelong in Prison Why Can’t We Stay Out

- 5 Of Relationships Fatherhood and Black Men

- 6 Twelve Things You Must Know to Survive and Thrive in America